How the Sacklers rigged the game

July 13, 2022

Originally published at pluralistic.net

Cory Doctorow

Two quotes to ponder as you read “Purdue’s Poison Pill,” Adam Levitin’s forthcoming Texas Law Review paper:

“Some will rob you with a six-gun, And some with a fountain pen.” (W. Guthrie)

“Behind every great fortune there is a great crime.” (H. Balzac) (paraphrase)

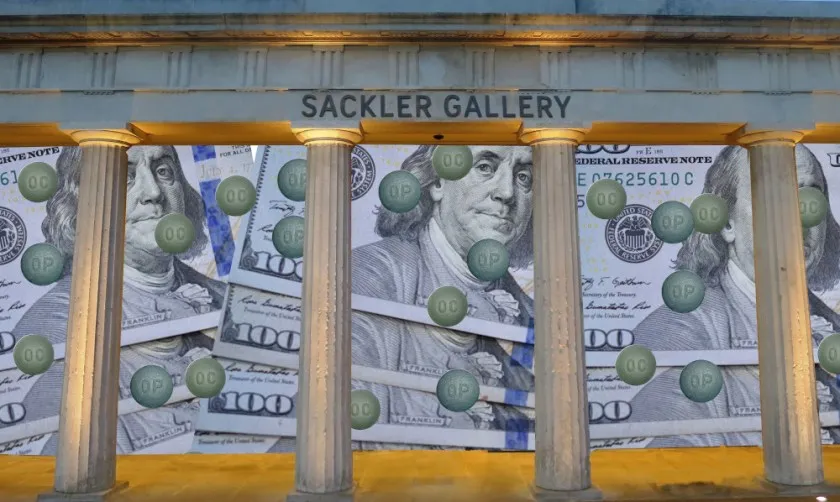

Some background. Purdue was/is the pharmaceutical company that deliberately kickstarted the opioid crisis by deceptive, aggressive marketing of its drug Oxycontin, amassing a fortune so vast that it made its owners, the Sackler family, richer than the Rockefellers.

Many companies are implicated in the opioid crisis, but Purdue played a larger and more singular role in an epidemic that has killed more Americans than the Vietnam war: Purdue, alone among the pharma companies, is almost exclusively devoted to selling opioids.

And Purdue is also uniquely associated with a single family, the Sacklers, whose family dynasty betrays a multigenerational genius for innovating in crime and sleaze.

The founder of the family fortune, Arthur Sackler, invented modern drug marketing with his campaigns for benzos like Valium, kickstarting an addiction crisis that burned for decades and is still with us today.

His kids, while not inventing the art of reputation laundering through elite philanthropy, did more to advance this practice than anyone since the robber barons whose names grace institutions like Carnegie-Mellon University.

The Sackler name became synonymous not with the cynical creation of a mass death drug epidemic and a media strategy that blamed the victims as “criminal addicts” – rather, “Sackler” was associated with museums from the Met to the Louvre.

Handing out crumbs from their vast trove of blood-money was just one half of the Sacklers’ reputation-laundering. The other half used a phalanx of vicious attack-lawyers who’d threaten anyone who criticized them in public (I personally got one of these).

The Sacklers could not have attained their high body count nor their vast bank-balances without the help of elite legal enablers, both the specialists from discreet boutique firms and the rank-and-file of the great white-shoe firms.

I’m not one to take cheap shots at lawyers. Lawyers are often superheroes, defending the powerless against the powerful. But the law has a bullying problem, a sadistic cadre of brilliant people who live to crush their opponents.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/10/duke-sucks/#devils

To see the sadism at work, look no further than the K-shaped world of bankruptcy: for the wealthy, bankruptcy is the sport of kings, a way to skip out on consequences. For the poor, bankruptcy is an anchor – or a noose.

When working people are saddled with debts – even debts they did not themselves amass – they are hounded by petty, vindictive monsters who deluge them with calls and emails and threats.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/19/zombie-debt/#damnation

But it’s very different for the wealthy. Community Hospital Systems is one of the largest hospital chains in America, thanks to the $7.6b worth of debt it acquired along with 80+ hospitals, which it is running into the ground.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/18/unhealthy-balance-sheet/#health-usury

CHS raked in hundreds of millions in interest-free forgivable loans, stimulus and other public subsidies and paid out millions from that to its execs for “performance bonuses.”

It also leads the industry in suing its indigent patients, some for as little as $201.

Debt and bankruptcy are key to private equity’s playbook, especially the most destructive forms of financial engineering, like “club deal” leveraged buyouts that turn productive businesses into bankrupt husks while the PE firms pocket billions:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/14/billionaire-class-solidarity/#club-deals

For mere mortals – those of us who can’t afford to hire legal enablers to work the system – bankruptcy is a mystery. If you know someone who went bankrupt, chances are they had their lives destroyed. How can bankruptcy be a gift, rather than a curse?

Purdue Pharma presents a maddening case-study in the corrupt benefits of bankruptcy. When it was announced in March, many were outraged to learn that the Sacklers were going to walk away with billions, while their victims got stiffed.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/03/31/vaccine-for-the-global-south/#claims-extinguished

Levitin’s paper uses the Purdue bankruptcy as a jumping-off point to explain how this can be – how corporate bankruptcy “megacases” have become a sham that subverts the very purpose of bankruptcy: to allow orderly payments to creditors while preserving good businesses.

Levitin identifies three pathologies corrupting the US bankruptcy system.

First is “coercive restructuring techniques” that allow debtors and senior creditors to tie bankruptcy judges’ hands and those of other creditors, overriding bankruptcy law itself.

These techniques – “DIP financing agreements,” “Stalking Horse bidder protections,” “Hurry-up agreements,” etc – are esoteric, though Levitin does a good job of explaining each.

More significant than their underlying rules is their effect.

That effect? Thousands of Oxy survivors and families of Oxycontin victims lost their right to sue the Sacklers and Purdue pharma because of these techniques. In return, the Sacklers surrendered about a third of the billions they reaped.

Depriving the victims of the Sacklers’ drug empire of the right to sue doesn’t just leave the Sacklers with billions; it also means that no official record will be produced detailing the Sacklers’ complicity in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Levitin: “The single most important question in the most socially important chapter 11 case in history will be determined through a process that does not comport with basic notions of due process.”

The Sacklers are not unique beneficiaries of “coercive restructuring techniques.” The rise of “prepack” and 24-hour “drive through” bankruptcies have turned judges into rubberstampers of private agreements between debtors and their cronies, with no look-in for victims.

It in these proceedings that the law descends into self-parody, more Marx Brothers than casebook. Levitin highlights the Feb ’21 “drive-through” bankruptcy of Belk Department Stores, where the judge was told that failing to accede to the private deal would risk 17,000 jobs.

The trustees representing Belk’s non-crony creditors were railroaded through this “agreement,” upon notice consisting of an “unintelligible” one-page, one-paragraph release opening with “a 630-word sentence with 92commas and five parentheticals.”

Sackler lawyers were geniuses at this game, securing judicial approval of a deal where the Sacklers’ personal liability to the Feds went from $4.5b to $225m. The judge heard no evidence about whether the Sacklers’ voluntary payout was even close to their liabilities.

The corruption of bankruptcy is bad enough, as the creditors for finance criminals are often small firms and workers’ pension.

The Sacklers’ case is far worse: they don’t owe billions in unpaid loans – they owe criminal and civil liability for the lives they destroyed.

The next area of corruption that Levitin takes up is the inadequacy of the appeals process for bankruptcy settlements. This, too, is complex, but it has a simple outcome: once a judge agrees to a settlement, it’s virtually impossible to appeal it.

In those rare instances where people do win appeals, they are still denied justice, because the appellate courts typically find that it’s too late to remedy the lower courts’ decisions.

That makes the business of “coercive restructuring techniques” (in which judges rubber-stamp corrupt arrangements between debtors and their cronies) even more important, since any ruling from a bankruptcy judge is apt to be final.

The third and most important corrupt element of elite bankruptcy that Levitin describes is the ability for debtors’ lawyers to pick which judge will rule on their case, a phenomena that means that only three judges hear nearly every major bankruptcy case in America.

“[In 2020] 39% of large public company bankruptcy filings ended up before Judge David Jones in Houston. 57% of the large company cases ended up before either Jones or two other judges, Marvin Isgur in Houston and Robert Drain in White Plains.”

https://www.creditslips.org/creditslips/2021/05/judge-shopping-in-bankruptcy.html

In other words, elite law firms have figured out how to “hack” the bankruptcy process so they can choose from among three judges. And these three judges weren’t picked at random – rather, they competed to bring these “megacases” to their courts.

This competition is visible in how these judges rule – in ways that are favorable to cronyistic arrangements between debtors and their favored, deep-pocketed creditors – and in the public statements the judges themselves have made, going on the record admitting it.

Levitin cites the groundbreaking work of Harvard/UCLA law prof Lynn LoPucki on why judges want to dominate bankruptcy megacases. LoPucki points out hearing these cases definitely increases “post-judicial employment opportunities” – but says the true motives are more complex.

Levitin, summarizing LoPucki: “[it’s more] in the nature of personal aggrandizement and celebrity and ability to indirectly channel to the local bankruptcy bar.. The judge is the star and the ringmaster of a megacase – very appealing to certain personalities”

Obviously, not every judge wants these things, but the ones that do are of a type – “willing and eager to cater to debtors to attract business…[an] assurance to debtors that…these judges will not transfer out cases with improper venue or rule against the debtor…”

Forum-shopping in bankruptcy is not new, but it has accelerated and mutated.

Once, the game was to transfer cases to Delaware and the Southern District of New York.

It’s why the LA Dodgers went bankrupt in Delaware, why Detroit’s iconic General Motors and Texas’s own Enron got their cases heard in the SDNY.

The bankruptcy courts have long been in on this game, allowing the flimsiest of pretences to locate a case in a favorable venue.

For example, GM argued that it was a New York company on the basis that it owned a single Chevy dealership in Harlem.

Other companies simple open an office in a preferred jurisdiction for a few months before filing for bankruptcy there.

Lately, the venue of choice for dirty bankruptcies is in Texas (if only Enron could have held on for a couple more decades!). Only two Houston judges hear bankruptcy cases, and any bankruptcy lawyer who gets on their bad side risks ending their career.

Once a court becomes a national center for complex bankruptcies, the bankruptcy bar works to ensure that only favorable judges hear cases there, punishing a district by seeking other venues when a judge goes “rogue.” The fix is in from the start.

Purdue did not want to have its case heard in Texas. Instead, it manipulated the system so that it could argue in front of SDNY Judge Robert D Drain.

It was a good call, as Drain is notoriously generous with granting “third-party releases,” which would allow the Sacklers to escape their debts to the victims and survivors of their Oxy-pushing.

Once Drain agreed to the restructuring, he ensured that the victims would never get their day in court, and no evidence – from medical examiners, auditors, and medical professionals who received kickbacks for every patient they addicted – would be entered into the record.

Drain is also notoriously hostile to independent examiners, “an independent third-party appointed by the court to investigate ‘fraud, dishonesty, incompetence, misconduct, mismanagement, or irregularity…by current or former management of the debtor.”

But getting the case in front of Drain took some heroic maneuvering by the Sacklers’ lawyers. Levitin tracks each step of a Byzantine plan that somehow allowed a company that gave its address in Connecticut to have its case heard in New York.

The key to getting in front of Judge Drain appears to involve literally hacking the system, by putting a Westchester County location in the machine-readable metadata for its filing in the federal Case Management/Electronic Case Files (CM/ECF) system.

CM/ECF does not parse the text of the PDF that it receives from lawyers; only the metadata is parsed. The company listed a White Plains, NY address in this metadata, even though it had never conducted business there.

Purdue seems to have opened this office 192 days earlier for the sole purpose of getting its bankruptcy in front of Judge Drain (they were eligible for Westchester County jurisdiction 180 days after opening the office).

Their lawyers even went so far as to pre-caption the case filing with “RDD” – for “Robert D Drain” – knowing that all complex bankruptcies in Westchester County were Drain’s to hear.

The fact that the Sacklers were able to choose their judge – a judge who was notorious for his policies that abetted elite impunity in bankruptcy – is nakedly corrupt.

This move is how the Sacklers are walking away from corporate mass murder with a giant fortune. The art galleries have started to remove their names from their buildings, but they’ll have a lot of money to keep themselves warm even if they’re shunned in polite society.

A couple weeks ago, a Texas judge ruled against the NRA, denying its bankruptcy, on the grounds that it was a flimsy pretence designed to escape liability in New York, where it was incorporated.

https://apnews.com/article/nra-bankruptcy-dismissed-a281b888b64d391374f24539a820d60f

For many of us, the NRA bankruptcy was a kind of puzzle. We went from glad that the NRA was bankrupt to glad that they WEREN’T, because for dark money orgs like the NRA, bankruptcy isn’t a punishment, it’s a way to escape justice.

The NRA case is evidence that the corruption of the bankruptcy system isn’t yet complete. That’s no reason to assume everything is fine. The Sacklers are developing a playbook that will be used to escape other elite crimes with vast fortunes intact.

(Image: Geographer, CC BY-SA, modified)