Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

December 19, 2023 at 10:50 am in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249899

Excellent, thank you!

December 17, 2023 at 12:44 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249894Not having read much of the work of their intellectual adversaries, I did not pick up on the degree to which the Davids caricatured their arguments when I read the book, which makes me curious to read them.

I think there are legitimate reasons why the Davids might have stayed away from using statistical or quantitative analysis.

For one, its possible that for much of the subject material, and if I remember correctly they mention this, there just isn’t much evidence, quantitative or no. One of the things they highlight is just how little we know about cultures beyond a certain time period. In this sense, their argument is intentionally framed as speculative and imaginative. Not very scientific perhaps, but my sense is that they were upfront about this.

I was reminded of a similar set of arguments in Mumford’s “Technics and Human Development,” where he argues that most of the important information about paleolithic/neolithic cultures (language, myth, knowledge, moral system) leaves no physical trace. The emphasis on certain quantitative evidence is to a certain extent unavoidable but nonetheless creates certain biases of inquiry and assumptions , for instance toward technological determination (e.g., weapons and graves).

Second, and much more importantly, I saw the book as having an explicit prescriptive purpose, which quantitative evidence may not have been particularly helpful for advancing. Namely, what the Davids are really interested in is making an argument about the future, not the past.

The way I see the Davids’ project is that it is aimed at expanding the range of imaginable possibilities for how humans might organize themselves, and especially in terms of alternatives to currently existing coercive/hierarchical orders. So by -for instance – downplaying the important role of war and violence in the past, they may have overstated the degree of autonomy humans generally have had, yet they are at the same time refusing to conclude that such (coercive, unequal) forms are inevitable. One way of looking at it is as a failure to do good science, but I think looking at this work as a book that is only concerned with science or scientific fact gives an incomplete picture of what they are trying to do.

There’s a popular anarchist slogan, “demand the impossible.” Because radical egalitarian political movements tend to be short-lived in modern (and ancient?) history, they are like statistical anomalies. So radical change always appears from the ‘facts’ as highly improbable if not impossible. Taking such a pessimistic view, however, unfortunately only reduces those odds. And the big-picture statistical view definitely seems to predispose one to such conclusions. The philosopher Françoise Proust once defined history as “the collection or recollection of sublime experiences of liberty.” I think DoE is written in this spirit.

Blair, you mentioned that some of the views the Davids are arguing against within the evolutionary camp are not actually held by contemporary social scientists. I am curious to read more of this literature. If you were to put forward the strongest possible rebuttal of the Davids argument, (i.e., of the evolutionary/technological/geographical determinism camp) what sources would you likely turn to?

Brian, your question of what is causing changes in the fertility rate is an interesting one. I think you’re right that many factors are at work, and that at least some important ones can be traced to capitalist dynamics. Some other factors to consider are that (1) declining infant mortality rates mean that one reason for having many kids (i.e., only some survive) is no longer as significant; and (2) increasing urbanization/decreasing subsistence farming means fewer children are now needed to physically maintain farmland.

The relationship between social reproduction and capitalism, and especially the ‘contradiction’ of the tendency for capitalism to destroy its own social foundation, is an old one in political economy (e.g., Karl Polanyi), and especially in Marxist and Marxist-feminist literature.

In CasP theory, this ‘contradiction’ is instead framed as the notion that sabotage has a nonlinear relationship to profit – too much sabotage and the society over which capital dominates can collapse. However, the existence of this nonlinear relationship doesn’t mean that capitalism is destined to self-destruct. As Jonathan pointed out above, one of the strengths of the capitalist social order appears to be its flexibility and adaptability.

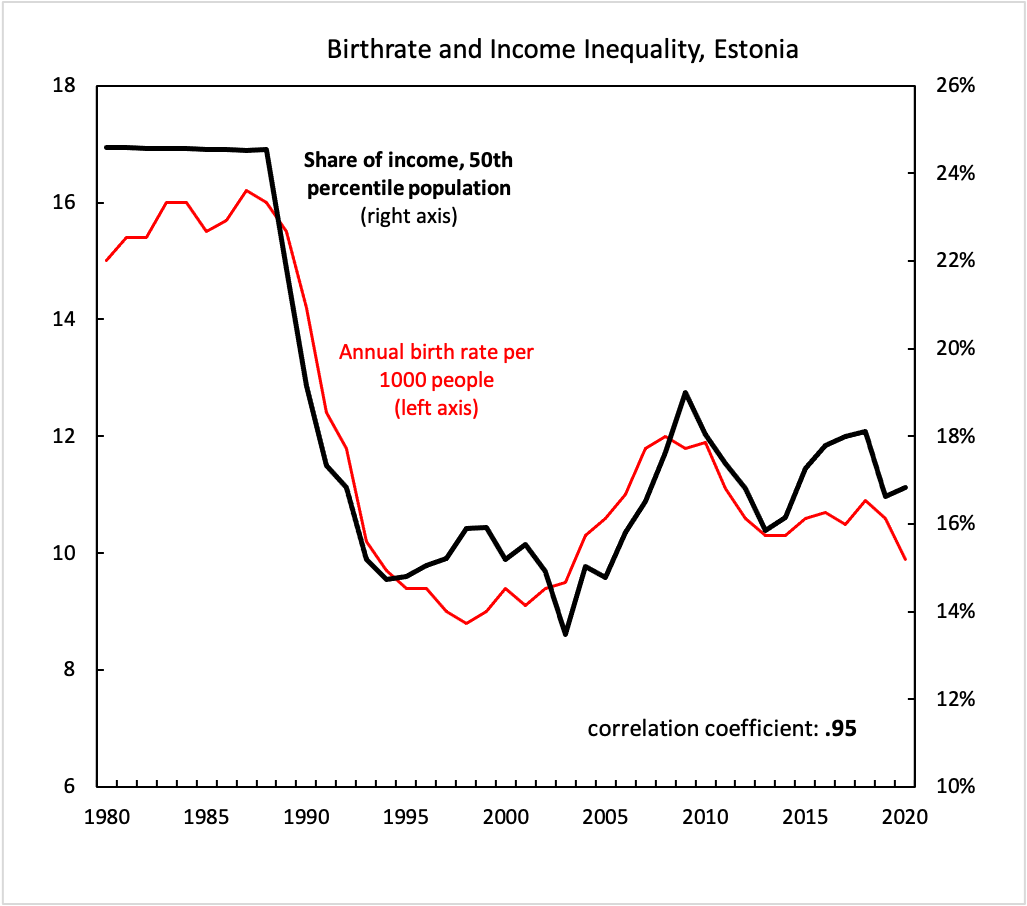

I did some looking at birth rate data in relation to income inequality (through the World Inequality Database) and I found some interesting leads. Here is the crude birth rate per 1000 people for Estonia, plotted alongside the income share of the bottom 50th percentile of the population:

I tested the comparison with a few other countries; Poland showed the same tight correlation; for Mexico, the correlation was weaker but still significant; and South Korea was impossible to compare because the inequality data was incomplete.

If there is any truth to this correlation, I would guess that changes in differential social power affect the birth rate and not the other way around, confirming your own hypothesis.

The question then becomes, how are capitalists adapting to the declining birth rates? In Canada, one central adaptation is increased immigration, which started in the 1960s and 70s and was a major factor in the shift of the Canadian national ‘identity’ from mono-cultural Anglo (of course excluding French-Canada and Indigenous Peoples) to our current ‘multicultural mosaic identity’. From the start, the need for more labour was a driving factor in the shift in immigration policy. Here’s the BBC from just last November:

“Immigration already accounts for practically all of the country’s labour force growth, and by 2032, it is expected to account for all of the country’s population growth too, according to a government news release. Earlier this month, the government announced that by 2025, they hope to bring in 500,000 new immigrants a year, up about 25% from 2021 numbers.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-63643912

This adaptation is not without obstacles. Immigration is politically unpopular among large parts of the working class, as they perceive new immigrants as competition, and as being accepting of worse working conditions and lower pay. I’m not saying this is true of immigrants, but this is clearly a dominant perception (e.g., it was a major driver of Brexit voting). I wonder if the immigration question in South Korea will begin to play a bigger role at some point due to these population dynamics.

February 23, 2023 at 5:05 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.00: Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method (Open Jan 01, 2023). #248916Thanks James.

Noting the contrast between the almost deterministic account of scientific change in Kuhn and Feyerabend’s more voluntaristic account is an interesting take. I certainly agree that Feyerabend is promoting the importance of heroic or militant action on the part of the scientist and is making a much more prescriptive argument than Kuhn’s more passive/descriptive sociological take (I haven’t read Kuhn in a while and I’d forgotten the lack of agency in Kuhn’s version of science). However, I took Feyerabend’s voluntarist view not to be exclusively a focus on the individual in the classical liberal sense, but more broadly a focus on the importance of the militant (Leninist?) ‘subject’, which can also be collective, but pretty much necessarily involves a minority. In addition to Mill, I read the influence of Lenin and Mao, whom he also cites occasionally and somewhat approvingly (See especially the very first note of the introduction!) Though he certainly focuses on individuals to illustrate his arguments, he also seems aware that these individuals are usually part of a larger (if still far fewer in number compared to the larger institutions) collective of scientists. I’m thinking of say, the Copernicus-Galileo-Kepler triad as a subject of the heliocentric model of the solar system, as opposed to each existing as a monadic and self-sufficient creative unit. At other points, Feyerabend minimizes/corrects the record on the importance of certain individuals, especially Galileo.

Though Feyerabend only cursorily draws connections from politics to science, and really only to further his own arguments, I find the parallels between the two (revolutionary science/politics) fascinating and crying out for further theorization. For instance, there is the observation that both science and politics have been revolutionized by a vanguard individual or set of individuals operating outside the perceived boundaries of the state of the situation (i.e., undertaking illegal/counter-inductive activities, propaganda, heresy, etc.). Michel Serres has noted that the foundations of Law and Science underpin one another, and that scientific change is often accompanied historically by an actual trial (“The meta-polemic of science and law, of reason and judgement, cannot be decided definitively and constitutes the time of our history”).

As Blair and James point out/imply, the implications of promoting this vanguardist viewpoint when taken to the extreme, may have an unreasonably high cost or verge on the absurd. What is interesting to me is this: the question of what scientific institutions would be like if some kind of counter-induction militancy where widely adopted, appears to entail a similar set of philosophical and practical problems to that of what a political community would look like without a coercive and dogmatic state apparatus. One specific problem that I think speaks to both Blair and James’ comments is that if science/politics is best pushed forward by a vanguard minority who essentially make up their own rules, how can such a dynamic coexist with stable and/or democratic governance?

- This reply was modified 3 years ago by CM.

January 16, 2023 at 11:37 am in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.00: Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method (Open Jan 01, 2023). #248842Thanks for your comments Blair and Pieter.

Blair, I think your frustration with Feyerabend is really interesting because it speaks to a larger debate about the relationship between science and philosophy of science. Many (if not most) scientists practice science without much thought to philosophy of science, or without much meta-examination of what it is they do and how they see the world as a distinct social group. They simply work with the theories, strategies and problems of their day (and within the institutional constraints of the day too). Richard Feynman takes the extreme (if facetious) view:

“Philosophy of science is about as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds.”

On the one hand I agree with this sentiment in the sense that, though philosophy of science can be useful to scientists, the two disciplines actually have quite different goals. The goal of science is the pursuit of scientific truths (e.g., ‘laws of nature’), while the goal of philosophy of science is to make compossible or consistent the truths that science produces with other regimes of discourse (e.g., history, logic, politics). On the other hand, I think that when it comes to the big conflicts/advances in scientific understanding, philosophical questions are usually there bubbling up from under the surface in the discourse.

Theory choice is a good example to illustrate how these questions come into play (what counts as evidence would be another). While scientists may abstractly agree that there is no ultimate theory of the scientific method (yet), when two competing theories appear to be equally supported by evidence, those debates about method suddenly become more important. You mention usefulness, for instance, as a solid criteria for theory choice. But should we really determine the truth of a theory based only on usefulness? And what exactly is the relationship between usefulness and truth? Most scientists would likely say well, usefulness is just one among a few or several key criteria. But this mix of criteria is hardly objective. Feyerabend’s goal is, in my view, to attack the view of philosophers of science like/especially Popper, who insisted that there is an objective method or set of practices which makes science distinct from everything else (pseudoscience, superstition, ideology, tradition, etc.). I’m not sure if Feyerabend has convinced me yet that “anything goes,” but I agree that there are also serious problems (for philosophy of science, not necessarily for science) with the notion that the practice of science follows a consistently objective logic.

One further comment: The way I’m trying to understand this phrase “anything goes” is that scientific truths, by definition, come into the world as an entirely new thing – they can’t help but break with the body of knowledge that came before it. Thus, the logic of the pursuit of scientific truth must necessarily be one whose rules can only come to be ‘known’ (i.e., philosophized) as that truth is integrated into (i.e., transforms) the body of scientific knowledge to which it is relevant. In other words, the possibility of the production of scientific truth is founded on the literal void in our knowledge of the world, and our knowledge of any consistent method of science is thus irreducibly historical (backward-looking). I think recognizing this kind of radical ignorance that makes doing science possible leads to, or at least implies the kind of theoretical anarchism that Feyerabend is articulating. This perspective admittedly comes more from my reading in Alain Badiou than it does my understanding of Feyerabend, so as I get further into the book my understanding of his meaning of the phrase may change.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 1 month ago by CM.

January 7, 2023 at 12:21 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.00: Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method (Open Jan 01, 2023). #248818I’ll start off the discussion with a couple of questions for others, along with my own initial thoughts.

1. Does Feyerabend’s general argument about the development of scientific theories roughly follow with or rub against your previously conceived notions of the structure of scientific progress/theory-formation and adoption?

2. What, so far, has surprised you in Feyerabend’s account?

For me, I’m finding his argument perhaps less radical than it is presented to be. The idea that knowledge production is fairly anarchistic is something I’m already familiar with, both from works like Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions and from post-structuralist or post-foundationalist accounts of epistemology (e.g., Foucault, Derrida). So I feel like I have already come to see knowledge production (or scientific truth-seeking, perhaps?) as an irreducibly historical process – limited/determined in various ways (like by available evidence, previously accumulated bodies of knowledge, etc.), but ultimately contingent on the creative processes of the human mind.

In terms of what surprised me, I love Feyerabend’s account of Galileo’s telescopes, and the initial problems with using them for astronomy. I had no idea telescopes were initially such poor tools for observation and measurement of the cosmos. His account also presents a great example of how entangled theory and evidence can be. I think that the powerful (implicit) role of theory in constituting what counts as evidence/fact also goes a long way to explaining why theories that (from my historically situated perspective) appear so poorly supported by evidence can live such long, illustrious lives in the minds of scholars.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by CM.

However, in the other way around, the relation could be true (systemic phenomena threatening power -> increased volatility), I think.

Thanks, Julien.

On the one hand, I agree that it is at least plausible that when systemic fear is high, volatility would also be high. It would be interesting to see if there is indeed an empirical correlation. I also think looking at how volatility, or changes in volatility are distributed (for instance, between large and small firms) in the context of the systemic fear index (and power index, for that matter) would be interesting.

On the other, as we’ve both noted, volatility is associated with a whole range of phenomena, meaning that its causes are to a certain extent over-determined. This makes it tricky as an analytical tool, especially with large aggregate measures like the CBOE VIX.

The CBOE volatility index measures the (expected) magnitude of price changes, whereas the systemic fear index measures the correlation between price and earnings-per-share. This means that the fear index is affected by both the volatility of prices and earnings. In other words, prima facie, an increase in volatility of prices could either undermine the correlation between price and earnings-per-share or reinforce it, depending on what is happening with earnings.

Nitzan and Bichler argue that the systemic fear index is positively associated (both empirically and theoretically) with the power index, which tracks stock prices relative to the wage rate (McMahon 2021 adds two further ways of measuring the power index). This means that as stock prices rise relative to the income of the general population, the power index (and by association, the systemic fear index) goes up.

Volatility appears to follow a different dynamic. Investopedia notes: “The [volatility index] generally rises when stocks fall, and declines when stocks rise.” This seems like common sense: when stocks go up, people are more likely to hold onto them then to sell. It also makes quantitative sense. If the magnitude of change is measured as a percentage, then when stock prices are higher, the same absolute change will register as a smaller rate of change, and therefore less volatile. I may be misinterpreting Investopedia’s claim, but its possible that the volatility index may simply be measuring a statistical regularity, and may have only a tenuous claim to measure ‘systemic’ phenomena.

Another thing to note is that larger firms tend to have less volatile prices than smaller firms, likely for the same reasons. People tend to trust, and therefore hold onto higher value stocks and the same absolute change in price registers as a smaller percent rate of change for the larger firm. The CBOE volatility index is based on the S&P500, which represents some of the largest firms, but there is a question of to what extent the S&P500 (or any group of firms) is representative of the ‘system’ as a whole.

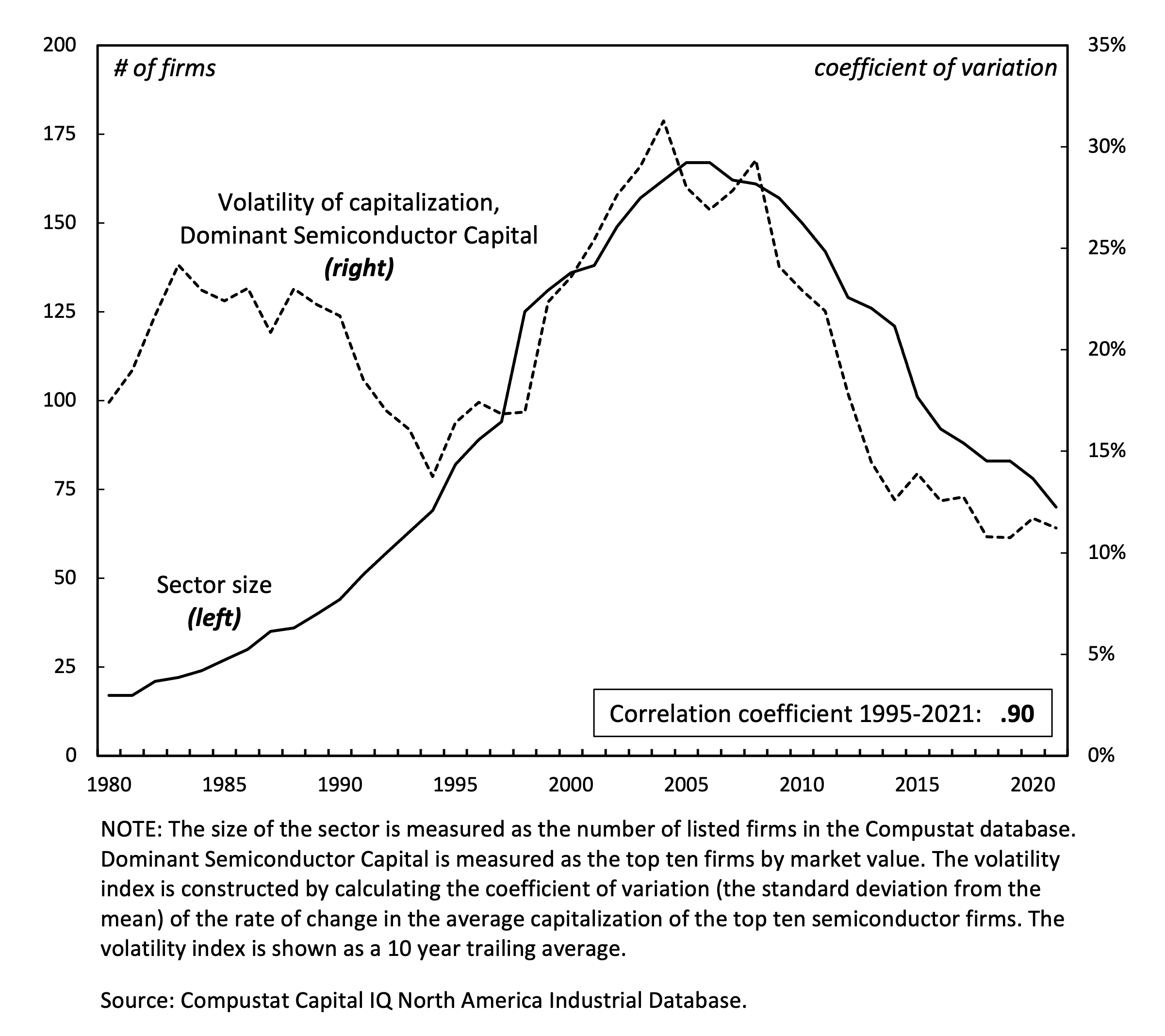

That being said, I have found evidence that the volatility of the capitalization of some firms is linked to power dynamics. In my master’s research project, I found that the volatility of the capitalization of dominant semiconductor manufacturing firms was correlated with the total number of listed semiconductor manufacturing firms on the Compustat financial database. I argued in that paper that this was evidence that the growth of new firms caused greater uncertainty in the future earning-capacity of the large established firms.

A rise in new firms, however, says very little about systemic fear. If anything, proponents of the capitalist system point to such growth as proof of capitalism’s essential dynamism and a significant reason for its long term stability, and new firm growth is cause for optimism (among capitalists at large).- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by CM.

November 9, 2022 at 5:54 pm in reply to: CasP Reading Group – Version 1 – Suggest Readings and Vote for ver. 1.00 #248569Already a great list!

I would like to add to the mix Culture and Materialism by Raymond Williams (1980, book, 305 pages) and Against Method by Paul Feyerabend (2010, fourth edition, book, 287 pages)

I would be also be happy to join.

I think one thing that would help is to start out with shorter readings/books. The one reading group I was part of rotated who got to choose the reading, but I think another good alternative would be to start with a short list of texts people are interested in reading and then pick randomly from the list.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

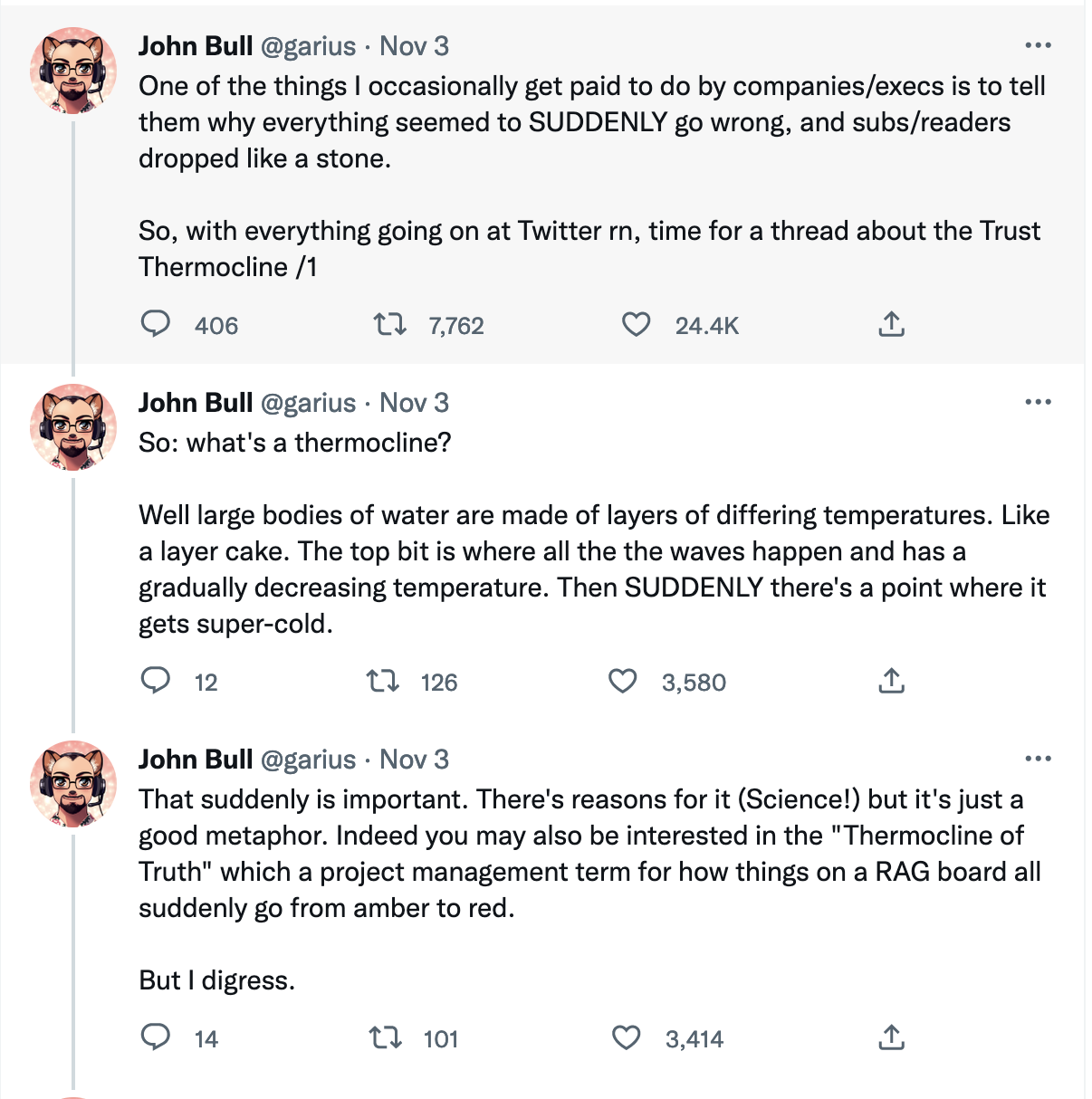

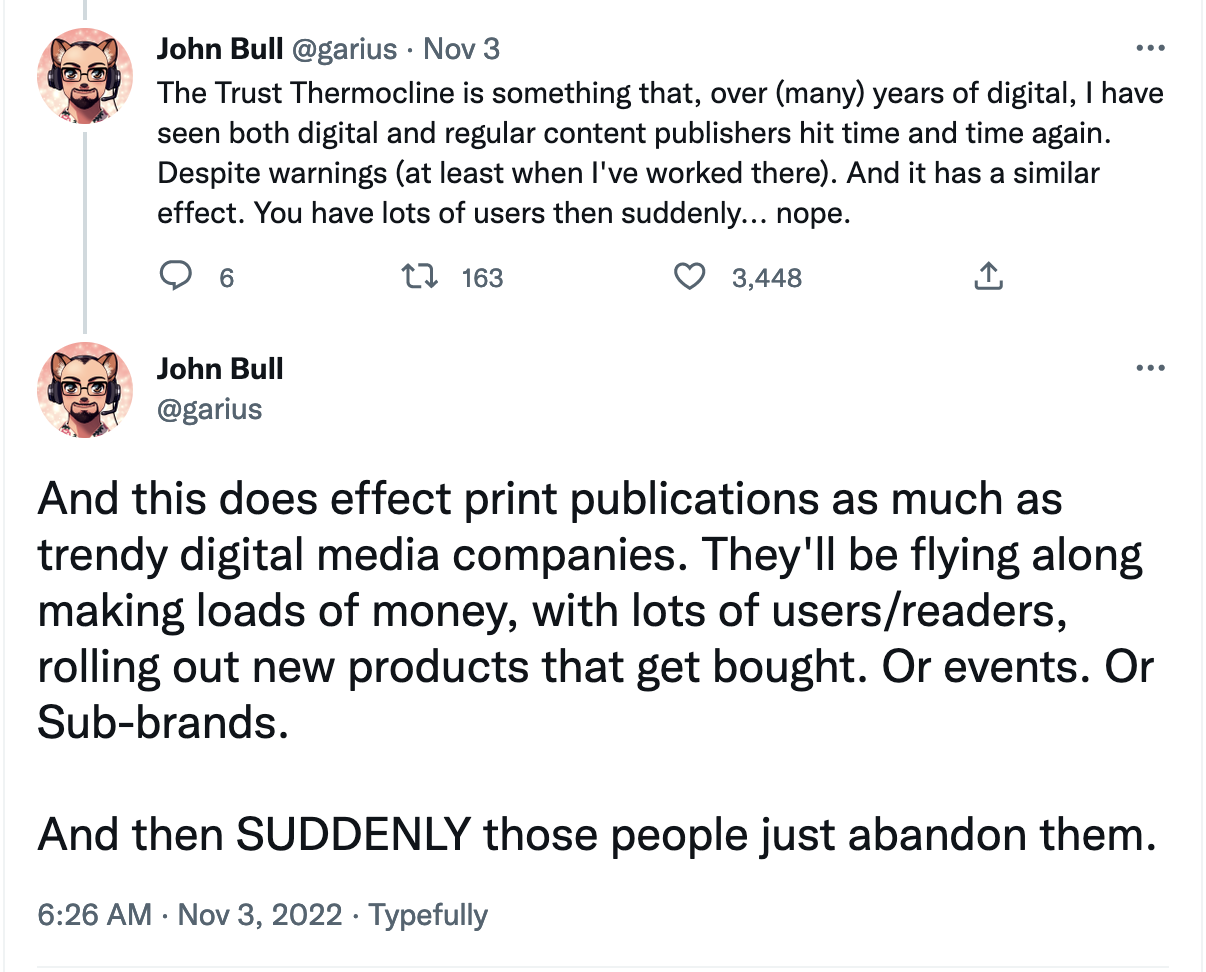

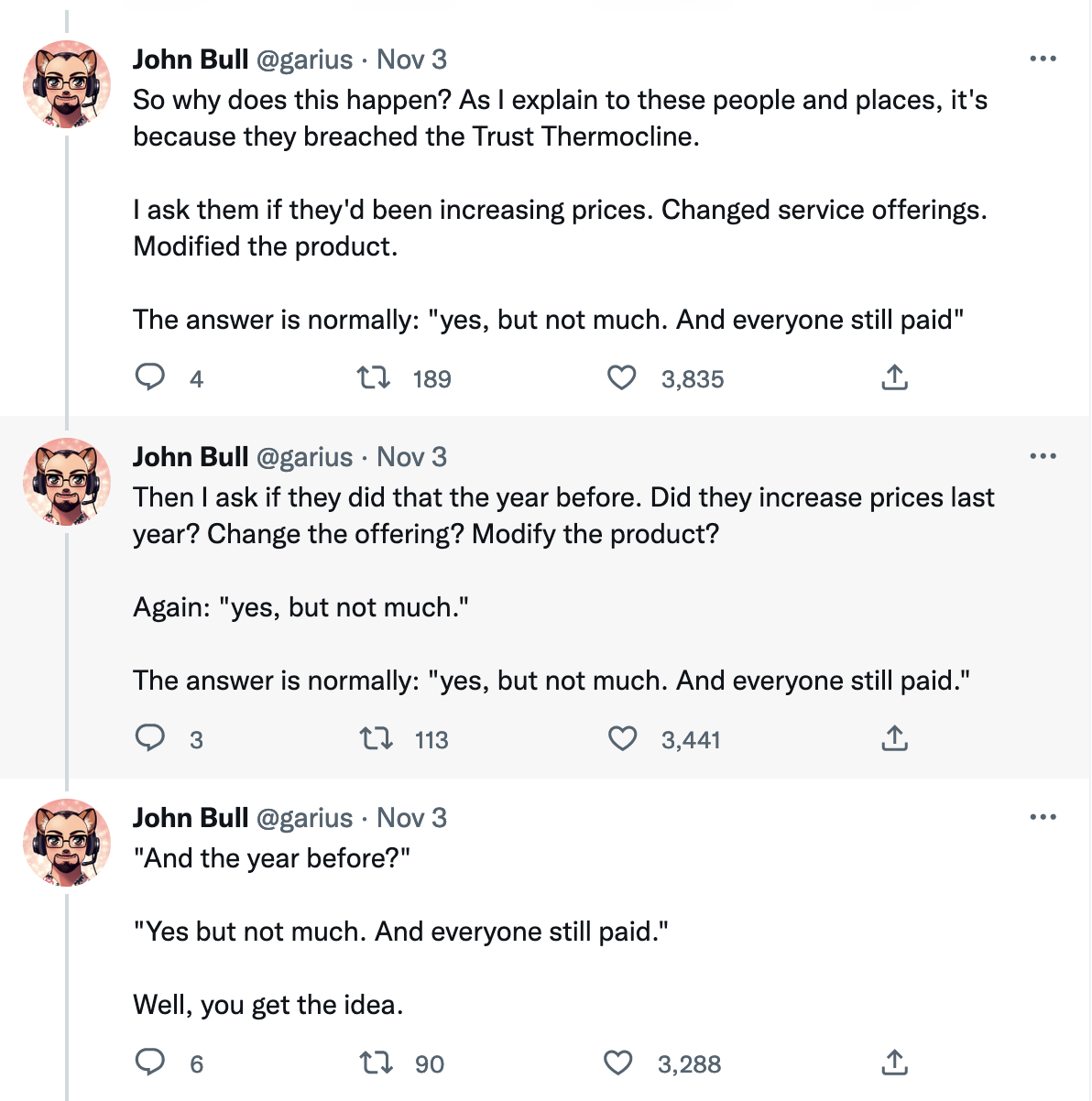

Here is a fun account from a software business consultant of the non-linearity of the relationship between sabotage and profit. He calls the point at which businesses sabotage their product/service so much that people stop using it “the trust thermocline.” Veblen would call it charging more than the traffic will bear. It seems there is a market for CasP analysis in the business world!

full thread: https://twitter.com/garius/status/1588115310124539904

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files.Yes, it might be a stylistic choice. There is certainly a clear ambivalence (but is it the Prince’s, or the author/director’s?) as to whether the new political order at all represents ‘progress’ for Italy…

James: I haven’t read the book but I watched Visconti’s The Leopard last winter. I thought the movie was really interesting, and visually stunning!

My favourite fiction book this year has been The Silentiary, by Antonio di Benedetto. It’s a darkly comic story of a man’s existential struggle against the world and its noise. It’s also about writer’s block.

I am looking forward to reading another from di Benedetto’s “Trilogy of Expectations” this fall, Zama.

I also enjoyed reading 2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson this summer. I think it qualifies as ‘hard’ sci-fi, meaning it spends a lot of time making the future ‘make sense’ in the context of our present – technologically as well as politically. It’s a bit more optimistic vision of the distant future than I would necessarily grant in that context, but that is part of what I liked about it – the writing is imbued with belief in and admiration for the creative powers of human society. It’s also a gripping adventure and a highly imaginative and rich exercise in world-building.

February 9, 2022 at 10:07 am in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247761

February 9, 2022 at 10:07 am in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247761Thanks! It’s definitely on my reading list.

February 9, 2022 at 10:06 am in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247760Thanks Jonathan,

I was dimly aware of this fact, but maybe not of its full implications.

It was my understanding that the Federal Reserve constructed a capacity index out of some weighted combination of “preferred capacity rate” (business maximum) and “practical capacity rate” (ostensibly closer to a measure of pure technical capacity). If the capacity utilization rate represented only the business maximum, it would make sense that markup and capacity utilization were in close alignment. If the business maximum is the simply most profitable utilization, it is conceptually equivalent to the utilization at which the highest markup is reached, and so the two would rise and fall together.

This indicates then, possibly, that the “business maximum” is more heavily represented in the capacity utilization index for the semiconductor business than any practical or technical measure (at least during 1984-2007). If this is the case, it could be that the divergence after 2007 reflects, as Scot said, the increasing relevance of fabless firms, for which the capacity utilization rate does not apply. If the fabless firms have a higher markup on average, it could produce the divergence in the chart.

-

AuthorReplies