Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Hi Max, thank you for your response.

if those definitions include power than it is unclear why we should think of power as an “emergent” property of coordination

The dimensions describe how coordination is structured, but power emerges from the interaction and recursive amplification of those structures. No single thread has ‘power’ in isolation. But when threads cluster in patterns—e.g., concentrated origins + exclusive participation + feedback suppression—that configuration manifests as Power Over.

What I’m trying to do is describe the structural conditions of coordination without assuming that power is already baked in. For example, the “Origin” of coordination doesn’t imply that power already exists—but rather that certain configurations of initiation can give rise to durable power asymmetries.

I see power as emergent not from the existence of coordination, but from the systemic patterning of coordination over time. That said, I’ll need to be very careful about not building implicit power relations into the model’s foundations, and I appreciate the reminder to watch for that.

Is a Thread really a basic unit? It seems to be a relation in itself.

You’re right that Threads are not universal like SI units. But their usefulness doesn’t lie in scalar equivalence—it lies in dimensional comparability. Like ecological niches or musical phrases, Threads aren’t commensurable by total value, but by structure, function, and pattern. The six dimensions allow us to map these structures relationally and compare across systems.

I probably shouldn’t use “unit” in the traditional sense (like a bit or meter). You’re right: a Thread isn’t fixed or scalar, and it can’t be made universal in a strict measurement sense without losing its richness.

But what I’m aiming for is something more like a relational building block—a structural pattern that can be analyzed across systems, not because it’s identical, but because it’s comparable along shared dimensions. Maybe “element” or “module” is a better term than “unit”?

I’m still feeling this out, and would really welcome your thoughts on whether that kind of “relational modularity” is a viable compromise between universality and context sensitivity. Have you come across other frameworks that try to balance those poles? Or would you suggest a different ontological starting point altogether?

Thanks again—this is exactly the kind of pressure-testing I’m hoping for as I refine the model.

Pieter

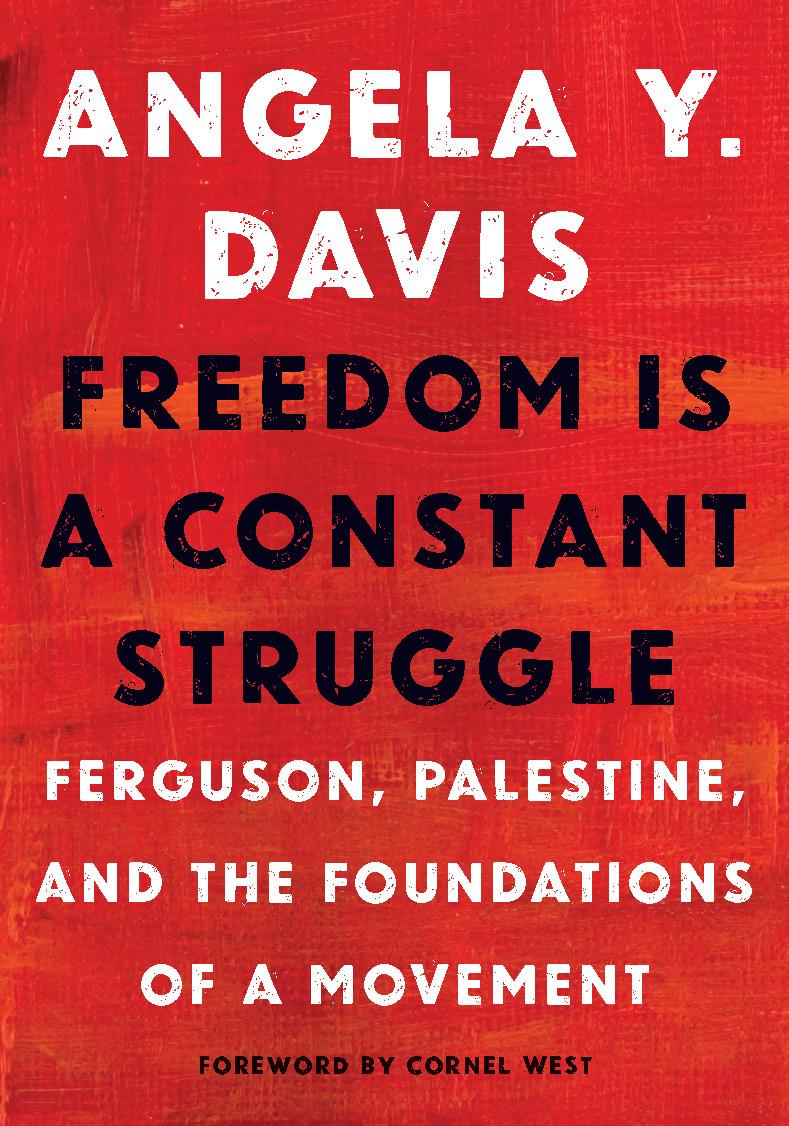

I just finished Angela Davis’s Freedom is a Constant Struggle, and honestly it hits hard in all the right ways. It’s a mix of speeches, essays, and convos that somehow manage to feel super immediate and timeless at the same time. Davis speaks from deep experience, and every page feels like it’s been lived through, not just thought up. Whether she’s talking about Ferguson, Palestine, prisons, or the long arc of Black resistance, she’s always connecting the dots, showing how these fights aren’t seperate, but part of something bigger.

What I really loved is how she moves between the personal and the global so smoothly. One minute she’s talking about political prisoners, the next she’s laying out how international solidarity can reshape the world. She lifts up the voices of people that are usually left out of the spotlight, and makes it clear that they’re not just part of the struggle, they are the struggle. There’s a kind of grounded hope in the way she talks about organizing, like she knows it’s hard and messy, but believes in people figuring it out together.

The future she’s pushing us toward isn’t just about tearing stuff down, but about building new things, schools that care instead of punish, communities that don’t rely on cops to feel safe, movements that cross borders without being co-opted. She makes a big deal about political education and staying reflective, and it shows. She’s not just calling for action, she’s showing how action needs a whole structure of understanding and trust underneath it.

If I had to say anything bad about it, it’s that some parts get a bit repetitive. Since it’s pulled from different talks and interviews, a few ideas come up again and again in the same words. That’s not a huge deal though, if anything, it kind of makes the message stick more. Still, for someone looking for fresh content every chapter, it might get a little old. But overall, this book is powerful as hell. Clear-eyed, full of heart, and honestly kind of nessasary reading right now.

Hi Jonathan,

Thank you so much for taking the time to respond. I really appreciate your thoughtful comments—they’re both generous and sharp, and they’ve helped me see the path ahead more clearly.

You’re absolutely right in identifying that I’m trying to develop a taxonomy of coordination, one where power is not just an effect of structure but emerges through the patterned dynamics of coordination itself. I’ve been thinking of it less as a fixed model and more as a kind of scaffold that might evolve through application and critique.

Your first point—about the difficulty of quantifying qualities—has been a persistent challenge. My idea of the “Thread” is meant to be a minimal, traceable unit of coordination that can still hold onto qualitative richness across multiple dimensions. But I hear your concern clearly: the more we try to measure, the more we risk reducing what makes coordination meaningful. I’m now thinking more seriously about hybrid approaches, possibly using ideas like dimensional mapping, narrative embedding, or even visual topology rather than pure quantification. If there are any frameworks you’ve found helpful in balancing this tension, I’d be very eager to learn.

Your second point—empirical grounding—is especially well taken. I agree that the best way to keep the model honest is to put it to work. I’m currently looking for solid case studies to investigate like Amazon’s logistics networks, coordination under revolutionary transitions (e.g., Cuba or Spain), and the divergence between federated vs. centralized platforms (Mastodon and Twitter). If you or others in the community have suggestions—especially examples that might break or stretch the model—I’d be grateful.

I see this project as iterative and dialogical. Your comments have already shifted how I think about the next steps. If it makes sense, I’d love to keep the conversation going as the framework develops, and I’m very open to being pointed toward prior work I might be overlooking.

Thanks again for helping orient me as I take these early steps.

Pieter

I obviously have not posted everything here that I have written down over the last 2 years. I am well aware that there are probably glaring holes in what I have shared here. But I would still appreciate any feedback or input anyone might have.

October 17, 2024 at 4:07 pm in reply to: The dark matter of CasP? What can’t we observe about capitalist power? #250158While in physics, dark matter cannot be observed directly, it is studied through its effects on the broader system with which it exists.

Similarly, we could use resource flows around unobserved or unobservable capital.

Private firms do business with on-private firms, and while this won’t provide the full picture about them, it will provide hints on how to refine data about private firms.

Organized crime cartels and syndicates are already providing a ton of data…. But to the state entities that are meant to be investigating them. This data would include resource inputs, crime statistics, social networks, and probably a plethora of sources I can’t think of right now.

January 16, 2023 at 4:43 am in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.00: Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method (Open Jan 01, 2023). #248841So I’ve just finished up to the suggested Part 9 for now.

I like the idea of counterarguments that specifically do not adhere to evidence related to specific theories, because such strategies can highlight flaws in the reasoning that matches most of the evidence.

A good example is CasP itself. CasP broke with the dogmatic view of Marxism and Neoclassicism, and rejected the evidence on offer from their respective theories. Instead, it proposed something almost entirely novel and generated new evidence that was able to directly challenge the assumptions of the heterodox theories of Capital Accumulation.

That being said, the book gives off a strong feeling so far of “My opinion is just as valid as your evidence-backed hypothesis” and this is sadly dangerous ground to be treading. While I do think that indigenous methods of gathering knowledge have much to contribute to the ways in which we view knowledge in its totality, and I do agree that “Western Science” spent centuries undermining indigenous forms of knowledge systems, I also think it would be a massive mistake to depict indigenous societies as “Noble Savages” that were correct on the basis of colonialism being a reprehensible practice. While Feyerabend doesn’t directly make this argument, I think that we could argue that it is implied.

I am looking forward to finishing the book though.

First, I am not as familiar with Marx’s class analysis as I should be, so any pointers on what to review to deepen my understanding of it would be appreciated.

Hi Scott, for reference, Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Capital Vol II and III are where he digs into his class analysis. Marx distinguishes between the bourgeoisie (Capitalist class capable of purchasing labour) Petit Bourgeousie (Wealthy people who do not purchase labour), Workers, and Lumpenproletariat (comprised of unemployed, disabled, homeless and outcast portions of society).

Second, doesn’t CasP already have some form of class analysis, i.e., the rulers and the ruled as mediated by the market and capital? Or does that just beg the question of how did the classes coalesce in the first place?

I think that it would be highly reductive to limit class analysis to the rulers and the ruled, as this essentially ignores the fuzzy lines that are often drawn by the intersections of hierarchies that interact in different ways and different contexts. Hence me bringing up this subject in the first place.

Regarding the sole proprietor and the GS employee, isn’t the difference in mobilization due to the fact the sole proprietor mobilizes individuals while the GS employee mobilizes hierarchies of individuals?

If we limit our framework to viewing only the economic realm and the workplace, then this might fit, but in essence, the small business owner is limited to their employees and their small financial reach in the ability to exert their will, while the GS employee can mobilize the hierarchy beneath them, and has the fiscal means to mobilize much larger swathes of the population outside of the workplace.

How should CasP’s class analysis account for hierarchically-induced dynamics, if at all?

CasP offers us the ability to look at how power is capitalized differentially at different intersections of hierarchical domination. Rather than simply looking at absolute wealth, or absolute relation to property, as the Marxist Class Analysis does, I think CasP offers us a more refined framework in which to approach Class Analysis. By looking at the Power of various hierarchies, from the business firm, to race relations, to governmental legal frameworks, to the various social phobias (homophobia, xenophobia, ageism, sexism) we can find the contexts of where these hierarchies intersect, and judge each individual’s relation to power, thereby introducing a highly granular and contextualized Class analysis.

January 3, 2023 at 9:33 am in reply to: Is power a thing in itself or the space between things? #248804I wonder if we’re unnecessarily limiting ourselves by leaving out power relationships that involve no obvious coordination. For example, a workplace or (abusive) family might have clear examples of coordination, but much of power in today’s world is typified with a sort of violent abandonment and withholding by absentee owners.

No Power Is An Island. There is no mode of power, or form of power, or concept of power, that can exist in isolation. It might be vested in, and wielded by a single entity, but it requires coordinated effort to create it, accumulate it, maintain it and exercise it.

Every cog, and spring, and sprocket, and lever that willingly operate in the Co-ordinated Power Machine, must by definition, gain more benefit from their coordinated support, than the average benefit of those over whom the power is exerted, and who must also form part of the machine, albeit without consent. But we can measure this benefit from coordination differentially, as in, establish the average benefit, and then see who benefits above the average.

Coordination is not always consensual. In fact, it is often conflictual. And even when it appears consensual, the explicit consent may be masking implicit or indirect conflict, coercion, and (dis)incentives. Absentee Owners may even exclude vast portions of the coordination machine from knowing that their efforts form part of the machine.

The notion of creorder leads me to wonder how much we can speak of “a specified will” rather than treat power as something that reinforces itself absent the need for a particular end goal.

Those with power over society may be limited by by the boundaries of their power, but they still get to enact their will. The fuzziness comes in because there are many wills contesting with each other, and the system within which they contest also has a will of its own, delineated by the sum total of the full creorder. When we look at a “specified will” there will be inaccuracies, because the framework will necessarily exclude the influences of other entities with equal, greater, or lesser powers, But it does offer us the ability to look at the problem with granular focus. Imagine, if you will, an analysis in which we take all the various specified wills, and we map then into a matrix of power relations. This will offer insights and predictions unlike anything we currently have at our disposal.

In attempting to make more “scientific” the concept of “power”, we also risk engaging in gatekeeping; limiting (if not sabotaging) its very real rhetorical impact and pro-social potentials. Not to mention the risk of ultimately “measuring” something rather unremarkable.

While I agree that this is a potential pitfall, I would argue that in the articulation of power as a clearly defined scientific concept, with quantitative and qualitative units of measure, we generate a fresh viewpoint, and enable the creation of a new linguistic milieu from which can be derived newer and more relevant rhetoric than the tired old language we have been using to largely no effect for the last 200 years.

January 2, 2023 at 5:17 am in reply to: Is power a thing in itself or the space between things? #248800I realize I answer very few of your original questions with my response, but I hope to untangle what might seem like a dichotomous problem by re-aligning it within a different framework

January 2, 2023 at 5:15 am in reply to: What’s the breadth of “Breadth”? What’s the depth of “Depth”? #248799Why is it breadth and depth only measured in terms of employees and earnings per employee? Is this simply because it is easiest to measure?

I could be wrong, but my understanding is that this narrowing of focus is because when we assess an entire market more broadly, we must necessarily be dealing with averages, rather than differentials. And so while we might get a general assessment of whether a market sector or industry is increasing depth or breadth, we lose view on the winners and losers within that market segment or industry, and that defeats the purpose of understanding the cycles of breadth and depth that individual firms go through in the process of accumulating power.

January 2, 2023 at 5:07 am in reply to: Is power a thing in itself or the space between things? #248798Great post Jordan, thank you for contributing this to the forum

B&N say in the book, and have re-iterated several times that “All Capital is Power, but not all Power is Capital”

This tells me that their work is predominantly about looking at Capital as a sub-category of power, rather than formulating a general theory of power.

Under capitalism, Capital is certainly the dominant conceptualization of power, and the most ubiquitously used, but it is not the full totality of the story.

Since reading CasP the first time, I have slowly shifted my focus from understanding Capitalism to understanding Power more broadly. And this is by no means a small task. Conceptualizations of power are extremely varied, and often dependent on the ideological basis that forms their origins. The Post-Modernists (while not being a single cohesive ideology) have proposed some very novel definitions of power and frameworks through which to try and understand power. Contemporary Sociological academic research into the ideas of empowerment has also come up with some interesting propositions.

Now, my thinking on the matter might be slightly unique, but I may also not be as well-read as is needed for a final approach. Thus far, I lean towards a conceptualization that Power is neither merely an entity, nor a relationship between entities, but rather, that it is a phenomenon that emerges out of the complex process of coordination. And in this regard it is both an attribute of entities, and a relationship between entities.

In this framing power is the result of the management of dependencies between entities, and management of the entities themselves, according to a specified will.

How coordination is enacted, will drastically influence what kind of Power results. Note that I do not take the deterministic stance, because all components of a complex system cannot be known, and as such we cannot guarantee that a specific type of coordination MUST result in a specific type of Power.

But, we can get close to certainty.

First, we have Power To. This is often referred to as Ability or Capacity. When we find the coordination of physical capability, and cultural setting, and historical influences, and intellectual capacities, and material conditions and kin relations, and social influences (to name but a few entities/components/activities), we arrive at the individual or small group’s Power To enact their will. Power To is the basis for the other manifestations of Power, because it is the coordination of the individual or small group within larger contexts that provides the functionality required to enact will at larger scales.

Next we have Power Over, more commonly referred to as Domination, or Authority. Power Over is achieved by one individual or group, subsuming, or extracting, or suppressing the Power To of another individual or group. This type of Power can occur at the interpersonal level, such as in relationships, or within families, or social groups, or it can happen at larger scales, such as within organizations, or institutions, or political parties, or social movements. But it’s defining characteristic is that it always has a deliberate power imbalance that is exploited and self-perpetuating. Power Over is, by its very nature, hierarchical. Meaning that in order to exist, and to continue existing, it must coordinate hierarchically.

Then we have Power With, which is commonly referred to as community, or cooperation, or collaboration. Unlike Power Over, Power With is the combination of the Power To of 2 or more individuals seeking to enact the same or similar wills. Power With can occur at the interpersonal level, and it can occur at larger scales, but its defining characteristic is that it is coordinated horizontally, eschewing hierarchies wherever possible (there are points I will clarify at a later stage about horizontal coordination within hierarchical hegemonies, that require communities to enact pseudo-hierarchical coordination at times)

Finally is Power Through. This is when it is not possible for an individual or small group to enact their Power To, and the surrounding community must eliminate the obstacles preventing such enacting, and set up the structures that will empower those individuals or groups to claim their power and enable them to enact their power.

These are the 4 types of power I have identified thus far, and there may be more, but for the moment, these suffice as a framework to explain almost all aspects of the modern world in which we find ourselves.

Capital clearly falls in the bracket of Power Over, while Colin Drumm’s idea of options is a mixture of Power To, but augmented by Power Over or Power With, depending on the specific context.

So right now, the deeper question for me is an analysis of the types of coordination and how the different forms of power emerge from these concepts of coordination.

December 20, 2022 at 4:05 am in reply to: Proximity to Legal Authority as a Measure of Power #248758As noted above in my response to Jonathan, I have already considered the idea of legislation formation’s “formative phase”, which you describe here as the “menu already being decided”

But I do like the idea of starting an analysis by comparing small and large firms in terms of capitalized power. I may lean quite heavily on Blair Fix’s work on Firming up Hierarchy

A great idea, and one that I will definitely look into.

For now, I need to start building up my reading list.

First additions:

Katharina Pistor’s The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and InequalityBerle and Means The Modern Corporation and Private Property

John Commons Legal Foundations of Capitalism

Morton Horwitz’s The Transformation of American Law (both volumes)

Adam Winkler’s We The Corporations

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Pieter de Beer.

December 20, 2022 at 3:49 am in reply to: Proximity to Legal Authority as a Measure of Power #248757This is certainly a useful way of envisioning the hypothetical process.

I’m definitely going to have to articulate my hypothesis as clearly as possible before I take on the task of collecting and analyzing real-world data.

And while I do think that this kind of non-linear correlation of capitalized power and proximity to authority would be very likely to match real-world data, I also suspect that the correlation would vary depending on which phase of the legislative process is being assessed. For illustrative purposes, I surmise that the legislative process can be broken up into 3 phases. The Policy Phase is where ideas are still being formulated and fleshed out. The Formalization Phase is where policy ideas are translated to ‘legalese’ and eventually codified. And the Judicial Phase is where legislation is re-structured and/or enforced by contestation within the judicial system.

For instance, the formative “Policy Phase” might have a much higher impact from lower proximity entities than from direct access entities. The “Formalization Phase” would have a much higher impact from direct access entities. The “Judicial Phase” would likely fluctuate in its representative proportionality (of low or high proximity entities). And while these phases should each have their own aggregate non-linear correlations between proximity to authority and capitalized power, I suspect that such an aggregate would hide a differential distribution of power between dominant capital and smaller, less influential firms. So I would need to do an analysis of both the general trend, and a more granular study of individual pieces of legislation and individual corporations and conglomorates.

The more I think about it, the more complicated it gets… which may, or may not, be a good thing

December 19, 2022 at 3:50 am in reply to: Proximity to Legal Authority as a Measure of Power #248751Thanks for the response Jonathan.

I understand that this idea has not been fleshed out sufficiently, and the terminology I am using might not clarify my ideas, but I plan on getting stuck into it. I will learn as I go.

To begin with, I will look at the process of law-making. As far as I understand it:

In the US, smaller pieces of legislation can originate directly from a member of Congress, who generally receives receive input from constituents, lobbyists, or staff on a particular issue. The member then directs the staff to take that policy idea to the Office of Legislative Counsel. Where attorneys turn the concept into the proper legislative language.

Both the U.S. House and Senate have Offices of Legislative Counsels. Those Offices have very specific language requirements on how a bill must be written.

From there, the bill language is reviewed by the Congressperson’s office before being dropped in a hopper and given a legislative number.

Then there is the process of the legislation passing through Congress, where it receives direct or indirect support or opposition from members of Congress. Regardless of support or opposition, there are layers of access and influence throughout the process. There are also courts that get to weigh in on the constitutionality of the legislation. There is the executive branch which has the ability to veto or approve the legislation. And then lastly there is the entire justice system that has the right to interpret the legislation in case law.

Larger bills run through essentially the same process but have more staff writing the initial documents, and more lawyers involved throughout the writing process to ensure it is compliant with the required legalese.

So here we have several levels of proximity.

Level 1 – We have direct access represented by the congress member’s staff and the congressperson , and the state organs involved in ensuring “legalese” compliance.

Level 2 – Then we have the influencers during the initial proposal (constituents, lobbyists, advisors, and staff) that are indirectly connected, who are one level removed from access.

Level 3 – Yet another level of influence sits behind these entities. Lobbyists are funded by interest groups, constituents are backed by influence networks, and advisors tend to represent specific schools of thought, which are shared by interest groups and influence networks.

Level 4 – Here we find the ultimate beneficiaries, predominantly these would be comprised of those accumulating capitalized power. But may also represent individuals with varied interests in strategic sabotage that are abstractly linked to capitalized power.

In the framework I am trying to envision here, the power accumulation will tend to occur in Levels 3 and 4, but I am trying not to make too many assumptions until I have had time to review some pertinent literature on the matter. I should also note that the lines here between the levels are not particularly clean or clear. Many congresspeople are the ultimate beneficiaries of capitalized power and can be both, directly and indirectly, related to legislation. Hopefully once I have read enough, I can figure out a better taxonomy for this proximity to power formation.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Pieter de Beer.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Pieter de Beer.

Hi Rowan,

While I do think CasP has thus far been applied as a “specific theory” rather than a “general theory” to use your language from above. I don’t think that its specific use is a limiting factor.

If what we are able to take from CasP is a framework of analysis for the current mode of power, then many of the attributes of the analytical framework would be generalizable to power relations, both historically, and in the future.

Capitalism is not the first mode of power we have experienced, and it is unlikely to be the last. And while the CasP framework is limited to observations about The State of Capital as a mode of power, it has identified certain rules about power that are already generalizable.

Sabotage is one of the first such rules. Hierarchies of domination, throughout history, have had to strategically sabotage their populations in order to maintain dominance. Whether we are looking at Slavery under Athenian democracy, or patriarchy’s suppression of matriarchal religions. While CasP makes very specific use of Sabotage, an argument can easily be made for its general application to power theory.

Then we have the Prefiguration of power as both means and ends. While CasP never phrases it this way, it becomes relatively obvious that when Capitalists seek Power for its own sake, the means by which they must achieve such power, is through the use of power. Anarchists have been using this kind of terminology for decades, but CasP has provided the quantitative and qualitative arguments that demonstrate it with extreme precision.

CasP did not come up with the idea of the Megamachine, but again they have provided quantitative and qualitative arguments for why the State of Capital can be classified as a megamachine, and then how both past and future modes of power can be analyzed along similar lines. The megamachine analogy actually compliments the analysis of power in terms of complex systems theory extremely palatable.

The Depth and Breadth Cycle ontology provides a solid basis for rejecting the idea that power is accumulated using singular strategic mechanisms.

And probably most important of all (in my opinion) is the elucidation of Creorder as a dynamic and ongoing structuring and restructuring of society according to the logic of power and resistance to power.

These things (and others I haven’t touched on) all make CasP far more than a theory focused on Capitalism, but rather a solid theory of Political Economy more broadly.

-

AuthorReplies