Complexity Science and Political-Economy: Post 1 – Networks

August 20, 2014

Shai Gorsky

This series of posts will explore some contemporary fields in “complexity science”. They summarize experiences from the Santa-Fe Institute Complex Systems Summer School 2014, with the hope of suggesting to readers useful research tools for political-economy. Please feel free to contact the author if you are interested in discussing or utilizing any of the approaches for research in the Capital as Power framework.

Networks

The following notes summarize (mainly) lectures by Prof. Aaron Clauset, University of Colorado, Boulder and the Santa-Fe Institute. Full graduate level course lectures notes (including further readings) are available online.

The recent rise of the internet and digital social networks has led to a surge in interest and research in network analysis. The mathematical basis for analyzing networks is somewhat older: Euler’s solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg riddle, proposed in 1735, is considered to be the cornerstone for a branch of mathematics known as Graph Theory. The city of Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) spanned over two banks of the river Pregel, with two islands and seven bridges over the river. Figure 1 shows a contemporary map of Kaliningrad and the approximate locations of the original seven bridges in red circles.

The challenge was to find a path that visits all the four land masses of the city and crosses each of the seven bridges only once. Euler abstracted the problem by treating only the land masses and the bridges (ignoring, e.g., distances or any other physical characteristics). In Figure 2, taken from Euler’s original solution, the four land masses are denoted by the uppercase letters A-D and the bridges are by the lowercase letters a-f.

A contemporary graphical representation of the same abstraction is suggested in Figure 3.

We leave to the reader to find the solution to the riddle. Our interests here lie elsewhere: in the abstraction of a city map – a highly detailed and complex object – to a graph comprised of only two types of components, and in the analytical treatment of graphs.

Some terminology: graphs are mathematical objects which have vertices (or nodes, actors) and edges (or links, ties). In our first example the vertices are the land masses (A-D in Figures 2 and 3) and the edges are the bridges (a-f in Figures 2 and 3). Vertices must be distinct objects, while edges are pairwise relations between these objects. The degree of a vertex is the number of edges that are connected to it. The term network, in our context, will be used interchangeably with the term graph. Thus, for example, the term “social network” will remain meaningless lest we define what the vertices are, what the edges are, and which vertices are connected by edges. A possible network representation of a social domain may include persons as vertices and friendships as edges. However, one may suggest other network representations of the same thing.

Some examples of popular network representations of various phenomena are given in Table 1:

Table 1: popular network representations

Network |

Vertex |

Edge |

| Internet | Computer | IP network adjacency |

| World Wide Web | Web page | Hyperlink |

| Documents | Article, patent or legal case | Citation |

| Power grid transmission | Generating or relay station | Transmission line |

| Rail system | Rail station | Railroad tracks |

| Neuronal network | Neuron | Synapse |

| Food web | Species | Predation |

| Banking networks | Bank | Lending between banks |

| Bitcoin | Bitcoin wallet | Transaction |

There are several types of networks. A Simple Network is undirected, unweighted and has no self-loops. Euler’s graph of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg is indeed such a simple network. When edges are directed – point from one vertex to another – the network is directed. When different edges are assigned with numbers the network is weighted. Several types of vertices may be introduced in a single network, and Multiplex Networks also have several types of edges.

What kind of questions can we ask about networks? What kind of answers does network science provide? We will survey here some quick examples of answers to the above questions.

Centrality

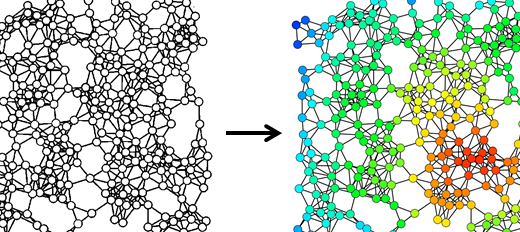

How important is a vertex? Can we quantitatively discern more important than less important vertices? The concept of centrality is supposed to provide some insight into this question. There are many measures of centrality of vertices. These measures receive network data as input, and assign each vertex with a number representing its centrality (different measures may provide differing quantifications). Figure 5 shows for example the Eigenvector Centrality measure of a given network structure, which assigns a higher centrality measure to vertices that are connected to vertices with a high degree. Google’s search engine famous page ranking algorithm is a variant of the Eigenvector centrality measure.

Community Structure

Community, of course, is a rich notion that cannot be fully covered by a network representation or any all-encompassing quantitative measure. In the context of network analysis, community structure is a group of vertices that connects with other groups of vertices in similar ways. We’ll provide two examples of community structures.

Suppose our vertices are divided into subgroups. To what extent are vertices more highly connected to vertices of the same kind? The assortativity coefficient quantifies exactly this. High assortativity indicates that vertices of the same kind have many edges between each other. Figure 6 demonstrates how a highly assortative network may look like.

The presence or absence of an assortative community structures is of high importance in, e.g., the study of epidemics. Define a network such that persons are vertices and edges are interactions amongst persons that allow infection with a disease. If an assortative community structure exists and vaccination is at hand, then the spread of infectious diseases may be more easily controlled by vaccinating the persons that correspond to the vertices that connect the subgroups of vertices, thus containing the disease in a smaller group.

Another widely discussed community structure is the core-periphery community structure. A core-periphery structure exists when a group of vertices that are densely connected to one another (the core) is connected to a sparser group (the periphery). Figure 7 demonstrates how a network with a clear core-periphery community structure may look like.

Indeed, the core-periphery analogy rings a familiar bell from the world-systems analysis tradition. Della Rossa, Dercole & Piccardi have demonstrated how network core-periphery characterization when applied to world trade data, generates the following core-periphery world map.

Other major topics in networks science involve the evolution of networks over time; building statistical generative models that may shed light on the processes that underlie the development of different kinds of networks; developing algorithms for predicting missing links; and detecting network change points over time (“phase transitions”).

There are many additional concepts and research interests in network science that we will not mention here. To conclude, we will suggest as a starting point for discussion some concepts from the Capital as Power framework that may benefit from network analyses. For one, the concept of dominant capital has been quantitatively defined so far somewhere between loosely and arbitrarily. Can a network representation of capitals be found such that centrality measures or core-periphery analyses will assist in identifying dominant capitals, and in deriving meaningful conclusions about them? Second, phase transitions of networks may, given a relevant network representation, in fact be regime shifts of capitalist differential accumulation. Third, can network community structure detection delineate coalitions of dominant capitalists? What may we learn about the robustness of such coalitions from network measures? Of their development over time? Fourth, ownership structures seem intuitively to be very susceptible to network analysis (by defining financial entities as vertices and ownership as weighted and directed edges), but full data is absent. Can a partial dataset be completed with inference methods?

In a nutshell, a successful network research depends on a good definition of the network, one that will allow interesting insights to arise from the various established network analyses. Doing so may indeed be a reachable goal.