An Evolutionary Theory of Resource Distribution (Part 3)

March 1, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

When it comes to earning income in a hierarchy, it’s not what you know that matters. It’s who you control.

This was the provocative idea that I proposed in Part 2 of this series on an evolutionary theory of resource distribution. In this post, I put this thesis to the test. I look for evidence of the power ethos inside modern firms.

A Recap

Before we get to the evidence, let’s review what I’ve done so far in this series. I’ve used ideas from sociobiology to develop an evolutionary theory of resource distribution. My thesis is that humans have a dual nature. We are both selfish and selfless.

Drawing on the work of E.O. Wilson and David Sloan Wilson, I’ve argued that our dual nature stems from a tension between two levels of natural selection. At the group level, selfless behavior is advantageous. But at the individual level, selfish behavior is advantageous. This tension, I’ve proposed, is key to understanding how we distribute resources.

In An Evolutionary Theory of Resource Distribution Part 1, I explored this tension from the top down. I looked at how groups compete with each other, but suppress competition internally. In Part 2, I explored the same tension from the bottom up. I looked at how humans use social relations to build groups, and how these relations get used for selfish gain.

The building block of large groups, I proposed, is the power relation. This is a bond in which one person submits to the will of another. Because power relations can be used to create a chain of command, they’re a potent tool for organizing large groups. But the benefits of concentrated power come at a cost. Individuals inevitably use their power to enrich themselves. So concentrated power leads to inequality.

I argued that this inequality should have a distinctive pattern. It should follow the power ethos: to each according to their social influence.

In this post, we’ll look for evidence of this ethos.

Can we measure power?

To test for the power ethos, we need to quantify power.

It’s at this point that my colleagues protest. “How can you quantify power?” they ask. “It has so many different forms!”

My colleagues are correct to point out this problem. The multifaceted nature of power has long been a thorn in social scientists’ side. Many social scientists have argued that concentrated power leads to inequality [1]. But because power is difficult to quantify, this idea has rarely been tested.

As a consequence, a promising theory of resource distribution has languished. There are compelling reasons to think that income (within hierarchies) grows with power (I reviewed some of these reasons in Part 2). But without quantitative evidence, why should anyone believe this theory?

They shouldn’t.

And there’s the crux of the problem. Yes, power has many forms. And yes, this makes it difficult to measure. But unless we quantify power, we can’t test the power ethos.

The solution is to bite the bullet and try to quantify power. We admit that power is complex. But we forge ahead anyway.

The two dimensions of power

To measure power, I propose that we break it down into two dimensions. We’ll distinguish between the number of people one influences and the strength of this influence. The purpose of doing so is to distinguish between qualitative and quantitative aspects of power.

The strength of one’s influence over others is a qualitative aspect of power. It’s determined by the obedience of one’s followers, which is difficult to quantify. This obedience, I think, is what most people mean when they speak of different ‘forms’ of power. Having thousands of Twitter followers, for instance, is not the same as having thousands of slaves. Slaves are far more obedient than Twitter followers. So these two forms of social influence are qualitatively different.

In contrast, the number of people one influences is easy to quantify. We just count people! The problem, though, is that comparing the number of people one influences isn’t useful unless the ‘forms’ of power are equivalent. So we have a dilemma.

Here’s where our two dimensions of power are useful.

While we may not be able to (easily) quantify the obedience of followers, we can probably agree on a rough ranking. We can agree that social media followers are less obedient than employees in a corporate hierarchy. And these employees, in turn, are less obedient than cult members.

Once we rank obedience, I argue that we can reduce power to a single dimension. As long as we stay within the same ‘zone of obedience’, we can measure power in terms of the number of followers. With this in mind, let’s look at Figure 1.

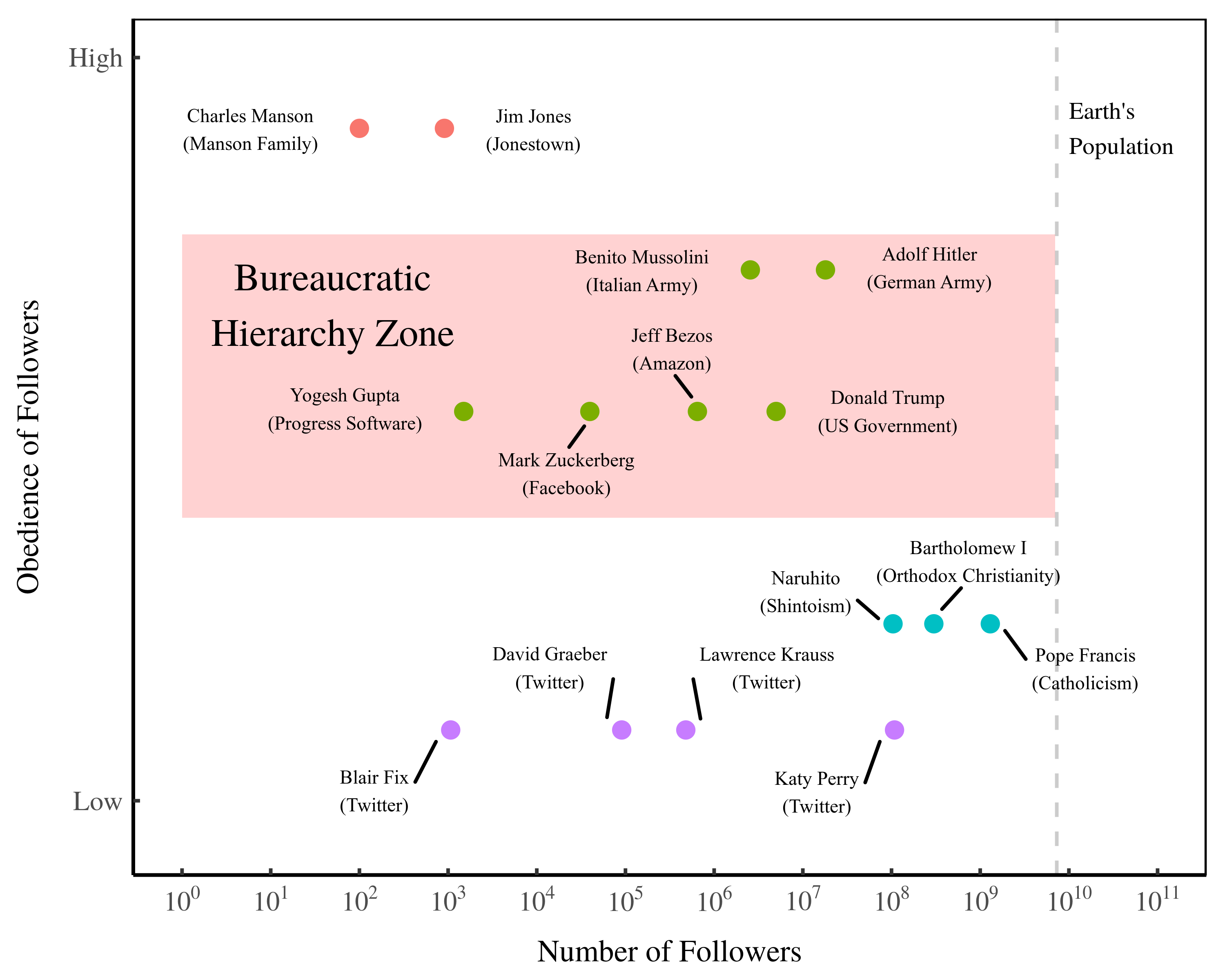

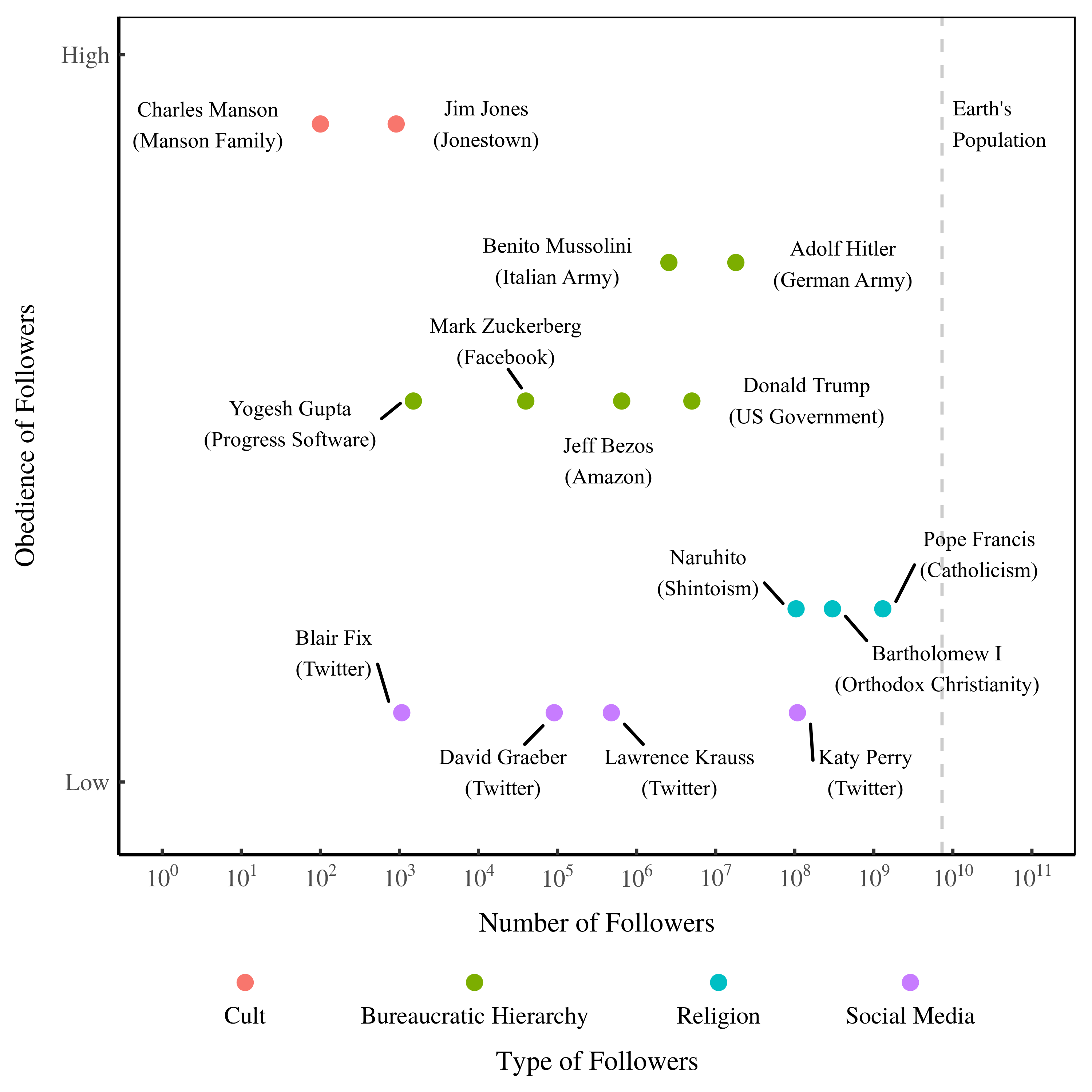

Figure 1: The Two Dimensions of Power. The y-axis ranks different forms of power in terms of the obedience of followers. The x-axis shows the number of followers of the given individual. For religious leaders, this is the number of people of the given faith. For CEOs, it’s the size of the firm they command. For government leaders, it’s the size of the government (or the military). For cult leaders, it’s the cult size.

Figure 1: The Two Dimensions of Power. The y-axis ranks different forms of power in terms of the obedience of followers. The x-axis shows the number of followers of the given individual. For religious leaders, this is the number of people of the given faith. For CEOs, it’s the size of the firm they command. For government leaders, it’s the size of the government (or the military). For cult leaders, it’s the cult size.

In this Figure, I’ve chosen a handful of individuals and split their power into two dimensions. The x-axis shows the number of followers of each individual. (Note the log scale. Each tick mark indicates a factor of 10). On the y-axis, I rank these forms of power by the obedience of followers. Full disclosure: I’ve pulled this obedience ranking out of my head. It’s based on my intuition about different forms of social influence.

Let’s first go through this obedience ranking. Then we’ll discuss why it’s relevant for measuring power.

We’ll start at the low end of obedience with social media followers. When you follow someone on Facebook or Twitter, you’re not pledging allegiance to them. You probably just think this person is interesting. So your level of obedience to the person you follow is low (or non-existent).

Religious followers are a little bit more obedient. The average religious person listens to their religious leader, but chooses which doctrines they’ll obey. For instance, many people who profess to be Catholics ignore most of the Pope’s decrees.

Still more obedient are members of bureaucratic hierarchies. These people are obedient because their job depends on it. In totalitarian regimes, even more is on the line. For this reason, I’ve ranked dictators (like Mussolini and Hitler) higher on the obedience scale.

At the upper end of obedience are cult followers, who can be so devoted to their leaders that they are effectively slaves. The members of Jim Jones’ cult are the most extreme example. Jones convinced hundreds of his followers to kill themselves in a mass suicide. It’s hard to think of a higher form of obedience.

Zones of obedience

The point of ranking obedience is to remind us that power has different forms. We shouldn’t compare Twitter followers with cult followers. But we can compare power within the same ‘zone of obedience’. Within this zone, we assume that everyone’s followers have the same obedience. We then reduce power to a single dimension: the number of followers.

So on Twitter, Katy Perry is about 100,000 times more powerful than me. She has 100 million followers, I have about 1000. And within corporate hierarchies, Jeff Bezos is about 400 times more powerful than Yogesh Gupta (who you’ve never heard of). Bezos commands about 650,000 Amazon employees. Yogesh Gupta commands a small tech firm with 1500 employees.

In this post, I’m going to stay inside the bureaucratic hierarchy zone of obedience. Here’s how I visualize it:

Figure 2: The Bureaucratic Hierarchy Zone of Obedience

Figure 2: The Bureaucratic Hierarchy Zone of Obedience

Inside the bureaucratic hierarchy zone, obedience is institutionalized. This means that obedience doesn’t depend on personal characteristics. Instead, it depends on institutional position. Amazon employees don’t obey Jeff Bezos because he’s Jeff Bezos. They obey him because he’s the CEO of Amazon. If I replaced Bezos as Amazon CEO (cue laughs), Amazon employees would then obey me.

The other important aspect of bureaucratic hierarchy is that obedience is mostly indirect. Amazon employees don’t directly obey Jeff Bezos. Instead, Bezo passes commands down the chain of command. Each Amazon employee then obeys their direct superior, who relays Bezos’ commands. Contrast this with power on Twitter, which is direct. Katy Perry has 100 million Twitter followers who listen to her directly (albeit flippantly).

The bureaucratic hierarchy zone is where the institutions of capitalism live. Bureaucratic hierarchy is how firms and governments are organized. More broadly, I’d guess that it’s how all large institutions in human history are organized. But that’s a topic for another post. Here, we’ll focus on modern firms.

When we’re inside the bureaucratic hierarchy zone, we’ll ignore variation in the obedience of followers. We’ll pretend that Mark Zuckerberg’s employees are as obedient as Jeff Bezos’ employees. By doing so, we can reduce power to a single dimension. Power is proportional to the number of subordinates one controls.

Hierarchical power

Within a hierarchy, I define an individual’s ‘hierarchical power’ as the number of subordinates plus one:

hierarchical power = number of subordinates + 1

I add 1 to the number of subordinates to signal that each person has control of themselves.

To count the number of subordinates, we add both direct and indirect subordinates. Here’s an example:

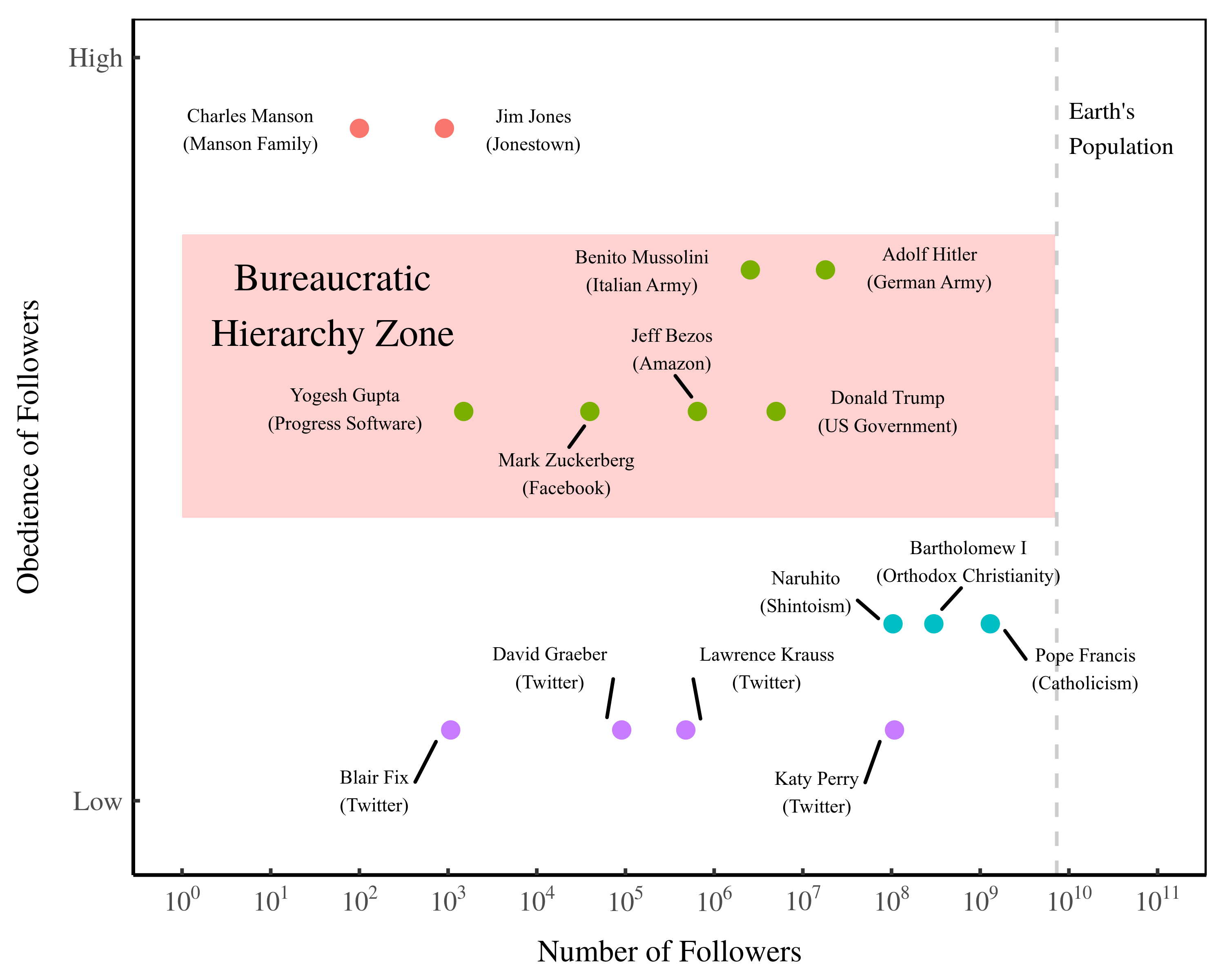

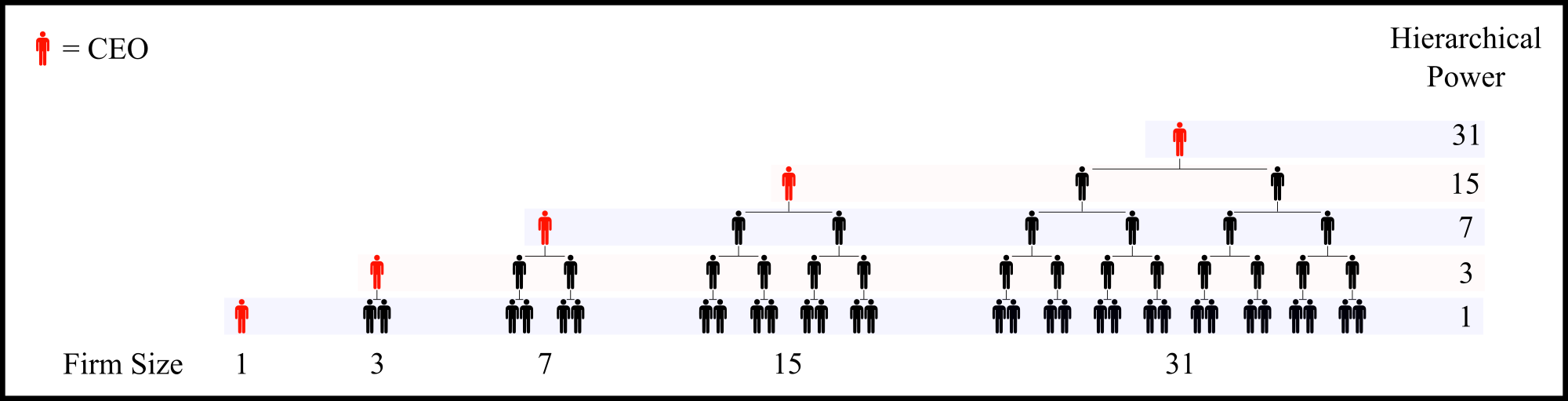

Figure 3: Measuring Hierarchical Power

Here, the red person has 6 subordinates, so their hierarchical power is 6 + 1 = 7.

With our measure of hierarchical power in hand, we’ll test for the power ethos inside firms. We’ll see if individual income grows with hierarchical power.

The power ethos among US CEOs

We’ll look first for the power ethos among US CEOs. We’ll study CEOs because it’s easy to estimate their hierarchical power.

Because CEOs command the corporate hierarchy, their hierarchical power is equal to the size of their firm. Here’s an example. If a firm has 100 employees, 99 of them are subordinate to the CEO. So the CEO has a hierarchical power of 99 + 1 = 100. Figure 4 shows this equivalence between firm size and the hierarchical power of the CEO.

Figure 4: The Hierarchical Power of CEOs. Because CEOs command the corporate hierarchy, their hierarchical power is the same as the size of their firm.

Figure 4: The Hierarchical Power of CEOs. Because CEOs command the corporate hierarchy, their hierarchical power is the same as the size of their firm.

We’ll use this equivalence to see if the relative income of CEOs grows with hierarchical power. To measure relative income, we’ll divide CEO pay by the income of the average worker. We’ll call this the ‘CEO pay ratio’.

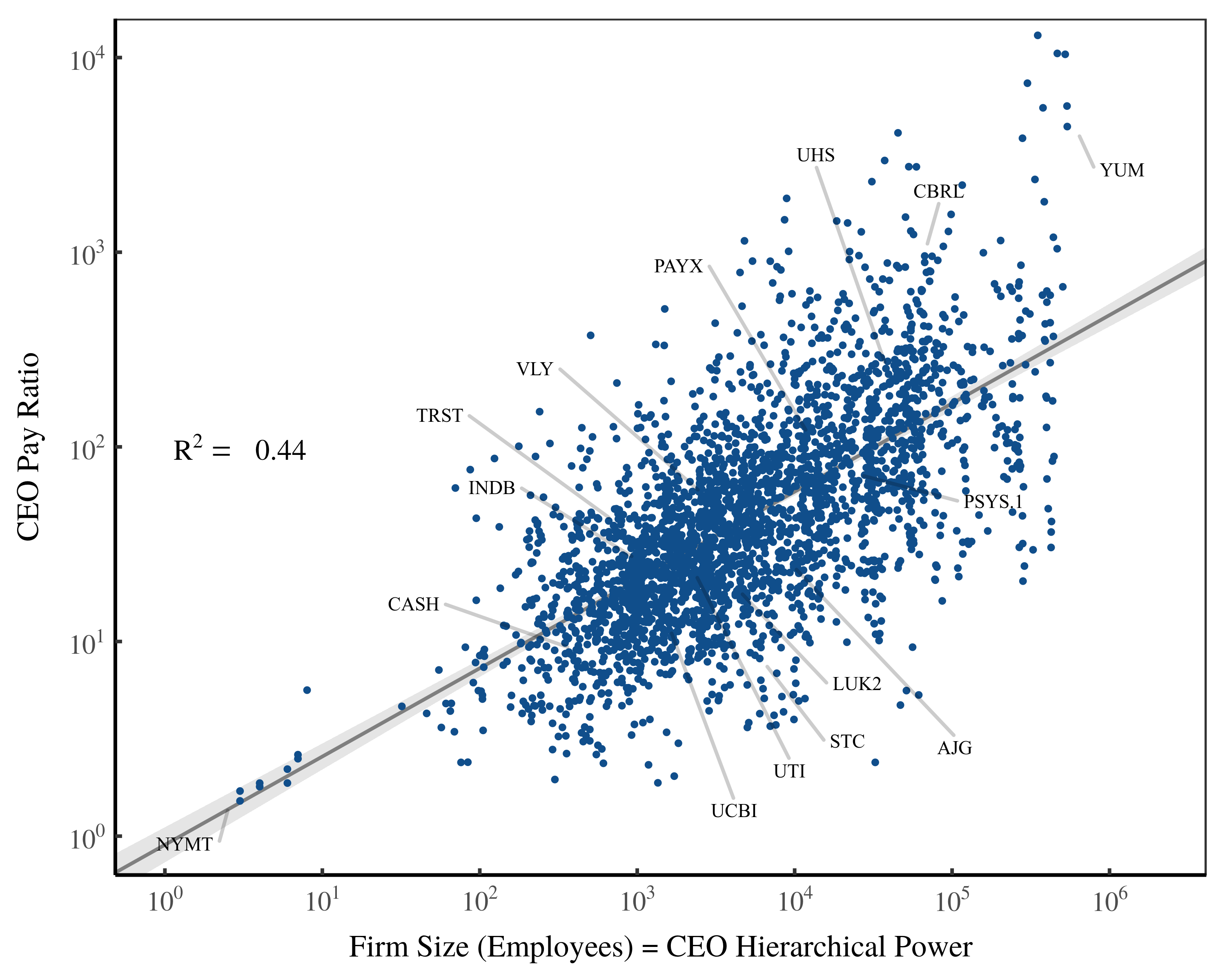

Figure 5 shows how the CEO pay ratio grows with hierarchical power among US CEOs. Among these CEOs, it seems that the power ethos prevails. Relative income grows with hierarchical power.

Figure 5: Evidence for the power ethos among US CEOs. Data is for about 3000 US CEOs covering the years 2006 to 2014. I’ve shown stock market tickers for a few of the firms. You can look up the tickers here. For sources and methods, see How the Rich Are Different: Hierarchical Power as the Basis of Income and Class.

The power ethos within firms

Next, let’s look at the income of all employees within firms. To do this, we’ll have to relax our standards for data.

The problem is that few social scientists have studied the structure of firm hierarchies. I’ve scoured the literature for years and found only a handful of quantitative studies. And these studies use differing methods to classify employees in the firm hierarchy.

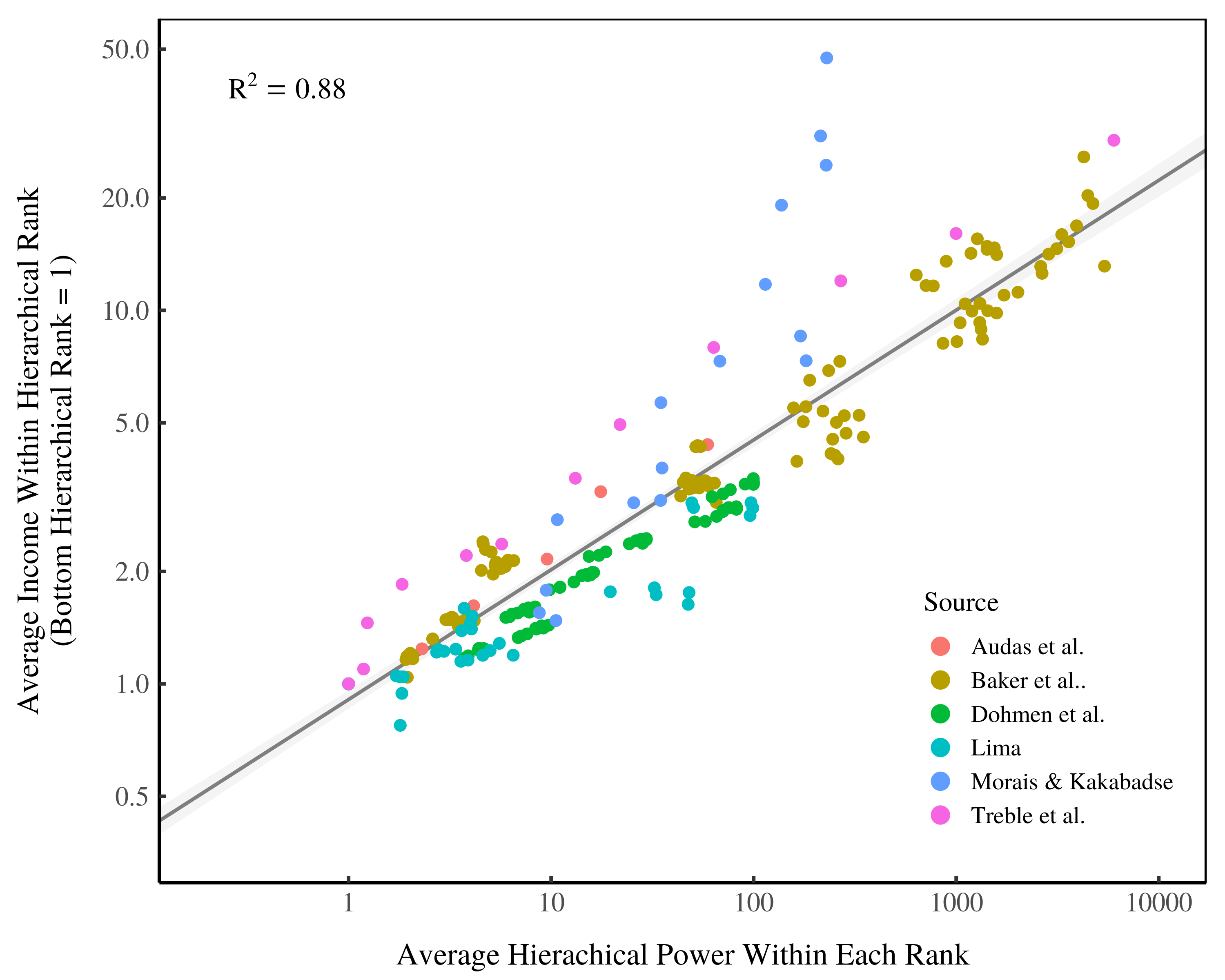

Despite inconsistencies in the empirical work, I’ll forge ahead and analyze the trends within these case-study firms. Figure 6 shows the results. In these firms, it seems that the power ethos prevails. Average income within hierarchical ranks is strongly proportional to hierarchical power.

Figure 6: Evidence for the power ethos within firms. The vertical axis shows average income relative to the bottom hierarchical rank of each firm. The horizontal axis shows average hierarchical power for individuals in each rank of the firm. Points indicate a hierarchical rank in a firm in a given year. For sources and methods, see Personal Income and Hierarchical Power.

Hidden skill?

When I show the above evidence to mainstream economists, I get a common response. “This isn’t evidence against human capital theory,” they claim. Instead, they argue that individuals with more hierarchical power are actually more skilled. And it’s this (unmeasured) skill that explains the returns to hierarchical power.

The lesson is clear. Human capital theory is still correct. I’m just not measuring the right things.

Mainstream economists Daron Acemoglu and David Autor have a (fittingly opaque) name for this type of thinking. They call it the “unobserved heterogeneity issue”. Translated to English, this means that economists tend to assume that their theory is true. They assume that all pay differences stem from skill, even when these skills are unobserved.

According to Acemoglu and Autor, this assumption is “not a bad place to start”.

I disagree.

Acemoglu and Autor are effectively saying that economists should barricade their theory from falsifying evidence. So if you find that measurable skills don’t explain income, don’t worry. Human capital theory is still correct. You just haven’t yet measured the ‘right’ skills. And if you find a variable that explains income better than skill, don’t worry. This variable is actually a proxy for some hidden skill.

This thinking is why human capital theory survives. And it’s why the evidence above doesn’t convince mainstream economists to abandon their theory. It’s impossible to disprove that an unmeasured skill causes the returns to hierarchical power.

The best we can do is show that measured skill doesn’t explain these returns. I’ve done this in The Trouble With Human Capital Theory. I show that common measures of skill (like education and firm experience) can’t explain the returns to hierarchical rank.

Still, the spectre of hidden skill haunts us. Is there a way to show that the hidden skills hypothesis is unreasonable? I think there is. To do it, we have to introduce time.

Time is important because there’s a mismatch between how we learn skills and how we acquire hierarchical power. We learn skills gradually. But we acquire hierarchical power in lumps.

This mismatch boils down to differences between the two traits.

Skills are an individual trait. To learn a new skill, you must forge new pathways in your brain. This takes time. Like all animals, our ability to learn has physiological limits.

But accumulating hierarchical power has no such limits. That’s because hierarchical power is a social trait. When you gain more hierarchical power, it’s your social position that changes (not you). And this change can happen literally over night. You can leave work as a middle manager and return the next day as the CEO. All it takes is a promotion, and you immediately gain more hierarchical power.

So skills grow gradually, while hierarchical power grows in lumps. Here’s why this difference is important. Suppose we find that during a promotion, income changes with hierarchical power. This would be a problem for the hidden skills hypothesis. Why? Because skills don’t change when you get promoted. The timing is too short. So in this scenario, it’s unreasonable to insist that hierarchical power is a proxy for skill.

With this in mind, let’s look at how income and hierarchical power change during promotions. I’ll use data provided by George Baker, Michael Gibbs and Bengt Holmstrom. (You can download the data here). This dataset tracks, over two decades, the pay and rank of employees within an anonymous American firm. I’ll call it the ‘BGH firm’, after the study authors.

Figure 7 shows promotion data from the BGH firm. For each promotion (or demotion), I plot changes in pay against changes in hierarchical power. You can see, in this figure, data for about 16,000 promotions and demotions.

Figure 7: Power ethos during promotions or demotions in the BGH firm. Each point represents an individual promotion/demotion. Color indicates the individual’s change in hierarchical rank within the firm. The y-axis shows fractional changes in individual pay. The x-axis shows fractional changes in hierarchical power. For methods, see Personal Income and Hierarchical Power.

The trend is clear. The more hierarchical power someone gains during a promotion, the more their income increases. For demotions, the reverse is true. The more hierarchical power someone loses, the more their pay decreases.

It’s hard to square these results with the hidden skills hypothesis. During a promotion, income and hierarchical power change suddenly. But skills don’t change like this. Moreover, skills rarely decline over time (until old age). Yet in the BGH data, we have many observations of a sudden loss of income after a demotion. Did these people suddenly become less skilled?

Doubtful.

A more likely explanation is that income in this firm is attached to rank. As individuals move up or down the corporate hierarchy, their income changes accordingly. Behind this movement of individuals, there is a connection between rank and hierarchical power. The result is that changes in income correlate strongly with changes in hierarchical power.

A universal ethos?

I’ve shown you evidence that the power ethos prevails in a sample of modern firms. But how general is this relation? Does income always grow with hierarchical power inside hierarchies?

I predict that it does.

Whenever we find institutional hierarchy, I predict we’ll find the power ethos. It doesn’t matter if we’re studying a feudal fiefdom, an archaic kingdom, a totalitarian regime, a democratic state, or a modern corporation. If there is hierarchy, I predict that access to resources will grow with hierarchical power.

So here is a task for empirical researchers. Go out and prove me wrong. Find a hierarchy and show me that income within it doesn’t correlate strongly with hierarchical power. I’m prepared to eat humble pie.

Having made a bold prediction, I’ll admit that we know very little about resource distribution within hierarchies. And that’s odd. It’s as though we (social scientists) have ignored the thing that most dominates our lives. Think about where social scientists work. We spend our lives in universities, which are large hierarchical institutions. And yet when we study income, we ignore this hierarchy.

This isn’t an accident. It’s happened because researchers have been driven by a bad theory — a theory that thinks income stems from characteristics of the individual. It’s time to put this approach behind us. Income is a social phenomenon. To understand it, we need to understand social relations. And there’s no better place to start than to study the power relations that dominate our working lives.

It’s time for a revolution in economics. It’s time to study hierarchy, and to ground this study in an evolutionary framework.

Notes

[1] Many people have proposed that income stems from power. Gerhard Lenski wrote a book about it (Power and Privilege). It’s a major part of Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler’s research. It’s also a popular idea among institutional economists like Thorstein Veblen, John Rogers Commons, Christopher Brown, and Marc Tool. And it’s been proposed by sociologists like Max Weber and Erik Olin Wright.