Why Scorcese is right about corporate power, Part 2

August 28, 2021

Originally published at notes on cinema

James McMahon

Part 1 introduced Scorcese’s argument in his Harper’s essay, which was about much more than Fellini. The first part also explained how we can connect Scorcese’s essay to the drive in the Hollywood film business for major film distributors to differentially accumulate, i.e., beat a benchmark that is relevant to dominant capitalists. By the end, we were left with an open question: how did major Hollywood studios differentially accumulate in the blockbuster era when their differential profits were actually stagnating? This question comes from the evidence in Figure 1, which was first presented in Part 1.

Note: Both series are smoothed as 5-year moving averages. Source: Compustat through WRDS for market capitalization and operating income, 1950-1993. Compustat for operating income of Hollywood firms, 1950-1993. Annual reports of Disney, News Corp, Viacom, Sony, Time Warner (Management’s Discussion of Business Operations for information on their filmed entertainment interests) for operating income, 1994-2019.

This post will focus on the change in attitude that established the blockbuster era. To firmly establish blockbuster cinema, Hollywood changed its attitude about the creativity of its filmmakers. Certainly, any version of Hollywood will need creative people to write, shoot, design, manage and act in films. However, around the early 1980s, the party was over for those whose creativity got in the way of Hollywood’s new path to differential accumulation: reducing risk.

Can we talk about what we just watched?

Kirshner’s history of the “New” Hollywood era (2012) begins anecdotally, with his personal memory of how often he and his friends would spend hours in cafes talking about the films they just watched. This anecdote, in my opinion, points to the heart of “New” Hollywood cinema. Films like The Friends of Eddie Coyle, Klute, Night Moves and California Split are hard to praise for how they look and sound. You can see the grain and muted colours of a typical “New” Hollywood film from a mile away. If you are watching the film at home, you might still not clearly hear the dialogue after raising your TV volume to 100. Nevertheless, a good “New” Hollywood film–and there are many–will certainly make you think, because no other era of Hollywood cinema is so explicit in its intention to make the moral ambiguity of a story as deep as an ocean. For example, in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, one of Robert Altman’s best films, McCabe (played by Warren Beatty) is hardly a hero, but Altman never lets your opinions only travel in one direction. McCabe is weak, but strong enough to fight. He is directionless but also a likeable martyr that hates the correct enemy: a mining monopoly that hires killers to terrorize a defenceless town.

In terms of theatrical attendance in the United States, the “New” Hollywood era was successful. We can see this with two measures of success. Figure 2 shows how the period between 1968 and 1980 had high theatrical attendance of the top five films per year. (Ticket price inflation is why theatrical attendance in the blockbuster era is lower than what one would have expected it to be.) Figure 3 shows a five-year percent change for the per capita theatrical attendance in the United States. A percent change of the series makes the relevant historical shift easier to see; all per-capita theatrical attendance after the 1940s is low by comparison, as theatrical attendance plummeted with the decline of the studio era and the rise of television. Figure 3 demonstrates that, while the level of theatrical attendance per capita was still much lower than what came before it, “New” Hollywood was able to produce positive five-year growth rates after two decades of shrinkage.

Note: Attendance equals total US gross revenues of the top five films, divided by average US ticket price. Sources: Bradley Schauer and David Bordwell, ‘Appendix: A Hollywood Timeline, 1960–2004,’ in Bordwell (2006). For years not covered in Schauer and Bordwell, see www.boxofficemojo.com for yearly gross revenues of individual films and National Association of Theatre Owners for average US ticket price.

Source: Finler (2003) for box-office receipts and ticket prices from 1933 to 1959; Bordwell (2006), ‘Appendix: A Hollywood Timeline, 1960–2004,’ for total attendance 1960–2004; www.natoonline.org/data/admissions/ for attendance 2005–19. IHS Global Insight for total United States population.

Not much to left to see if you ain’t here for blockbusters

In the two figures above, “New” Hollywood earns its name, as the era is defined by the ways studios successfully bounced back by embracing young, often inexperienced, filmmakers, whose film projects were infused with the social issues of America in the 1960s and 70s. There were cracks in the business-artist relationship from the very beginnings of “New” Hollywood–e.g., the studio treatment of Elaine May–but some of cracks that appeared in the mid-1970s were so big that this more free-spirited version of Hollywood was under threat to end almost as soon as it began.

The growth of the financial problem with “New” Hollywood was caused by Hollywood itself. Hollywood studios in the 1970s liked the newest post-studio-system distribution strategy, saturation booking, which is the act of releasing a big film like The Godfather, Part I in as many theatres as possible. Yet saturation booking needs a lot of people to come to the theatres, and the early problems with saturation booking would only be solved when Hollywood was more effective at using the saturation-booking strategy. The ability for saturation booking to be the solution to its own problems existed because Hollywood in the 1970s was a curious mix of proto-blockbusters, auteur blockbusters, and hard-to-market films produced by directors like John Cassavetes, Hal Ashby and Robert Altman. Look beyond the two most obvious financial successes of the 1970s–Jaws and Star Wars–and there are examples of this decade having qualities that undermined the interests of a Hollywood system that was now hungry for pure, uncut blockbusters. First, if blockbusters were to be high-octane fuel for the big engine of saturation booking, Hollywood studios would need to learn how to design enough “must-see” films for the top financial tier. As shown in Figure 4, this lesson was first taught in 1976, the year that was sandwiched between Jaws and Star Wars. Jaws created a new pecuniary standard for high-grossing films, and in this environment, the great financial success of Rocky–the highest-grossing film in 1976–was, as Cook describes, “puzzling and unnerving” (Cook, 2000, p. 52). Rocky was a low-budget project that featured, at the time, a cast of unknown actors. Its unexpected success twisted the knife in the side of designed-to-be-blockbuster films like King Kong (1976) and The Deep (1977), two films that could not repeat the financial success of Jaws.

Note: Attendance equals total US gross revenues of the top three films, divided by average US ticket price. Sources: Bradley Schauer and David Bordwell, ‘Appendix: A Hollywood Timeline, 1960–2004,’ in Bordwell (2006). For years not covered in Schauer and Bordwell, see www.boxofficemojo.com for yearly gross revenues of individual films and National Association of Theatre Owners for average US ticket price.

This frustration with Rocky needs to be viewed through the lens of risk. In both its technical and conceptual senses, risk is relevant to the study of how Hollywood, as a business, utilizes social creativity. The conventional wisdom is that cinema is a very risky business enterprise, which means that even the biggest Hollywood firms are uncertain about their financial success. Yet, we will see going forward that Hollywood has devised strategies to reduce the possibility that the future of culture will be radically different from what capitalists expect it to be. This making of order does not eliminate risk entirely. Rather, by exercising corporate power again and again, industrial art of filmmaking and the social world of mass culture can be transformed into an order of cinema, in which film projects are weighable and calculable in terms of future expectations. Under such historical conditions, estimations of a film’s social significance can, with a degree of confidence, be low risk or “sure bets”.

For the blockbuster style to be low risk, Hollywood needed to selectively nurture the “right” type of creativity. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were certainly proving their worth early on, but many of their contemporaries in the late 1970s were making auteur/blockbuster hybrids that proved to be incompatible with the saturation booking strategy. On the one hand, the production costs of films like Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, Peckinpah’s Convoy, Friedkin’s Sorcerer, Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Scorsese’s New York, New York, and Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate were far too big for a small-release strategy to be profitable; on the other hand, the form and content of these films were also too esoteric to ever reach the revenues plateau of a Jaws or a Star Wars.

Figure 5 helps illustrate the transformation from the 1970s to the current era of Hollywood cinema, 1980-2019. The figure is a proxy for the consumer habits of American cinema. It presents the volatility of attendance for both the top three and top five films per year. Volatility is computed in two steps. For both the top three and the top five films per year, the annual growth rates of total attendance are computed from the 1940s to 2019. The two series in Figure 5 are measures of, for each year, a 20-year trailing standard deviation of these growth rates.

Note: Attendance equals total US gross revenues of the top five films, divided by average US ticket price. Sources: Bradley Schauer and David Bordwell, ‘Appendix: A Hollywood Timeline, 1960–2004,’ in Bordwell (2006). For years not covered in Schauer and Bordwell, see www.boxofficemojo.com for yearly gross revenues of individual films and National Association of Theatre Owners for average US ticket price.

Interestingly, the volatility of attendance in the 1970s was similar to that of the 1960s and even the mid-1950s–two periods when saturation booking was not yet a method of distribution for mainstream films. Thus we can surmise that while the theatrical events of Billy Jack in 1971, The Godfather in 1972, Jaws in 1975 and Star Wars in 1977 were big in terms of levels of revenues, they had yet to translate into, for interested capitalists, high levels of confidence about the predictability of future earnings. To be sure, having single-handedly pulled in around 128 million attendances in the United States, Jaws was an example to be mimicked immediately. Justin Wyatt describes the saturation-booking strategy that followed on its heels:

Following Jaws, high quality studio films developed even broader saturation releases; in 1976, King Kong (with a 961 theater opening); in 1977, The Heretic: Exorcist II (703 theaters), The Deep (800 theaters), Saturday Night Fever (726 theaters); in 1978, Grease (902 theaters) and Star Trek–The Motion Picture (856 theaters) continued to expand the pattern of saturation release and intense television advertising.

Wyatt, 1992, p. 112

Despite this flurry of wide releases, however, Figure 5 illustrates that there is still a difference between the 1970s–a decade when blockbuster cinema was still in its infancy–and the contemporary period from 1980 to the present–a time when blockbuster cinema has become Hollywood’s predominant style. The two series–“Top Three Films” and “Top Five Films”–both start their decline in the 1980s and reach their lowest levels in the 2000s. By 2011, the 20-year trailing standard deviation for the attendance of the top three films was 48 percent less volatile than it had been in 1980. The same can be said for the attendance of the top five films.

Next post: Seeking low-risk cinema

This reduction in the volatility is neither accidental or a lucky externality of general market behavior. The next post will show examples of where, I believe, we can see Hollywood using capitalist power to reduce risk. In the day-to-day experiences of filmmaking, this mode of power can appear in flashes, such as when executives “give notes” to creatives or when studios suggest casting stars to boost a film project’s “bank-ability”. However, even when the sabotage of filmmaking is micro enough to be imperceptible (much like the slow boiling of a frog in a pot?), the key is that the oligopoly at the centre of Hollywood has the power to act when creativity is perceived to be “too risky”. Some film projects, on account of their subject matter or style, can be effectively withheld from the market because no major firm will purchase the rights to distribute them. A film project may be able to find financing, but under a contract that stipulates conditions about form, content, budget, cast, crew, etc. A film can be produced, but management will have a role in the direction and pace of creation. And if business interests are still sceptical about their investment in potentially chaotic artistic creativity, the right of film ownership often includes the right of “final cut”–i.e., the right to modify a film before it is released but after the director presents his or her final version (Bach, 1985).

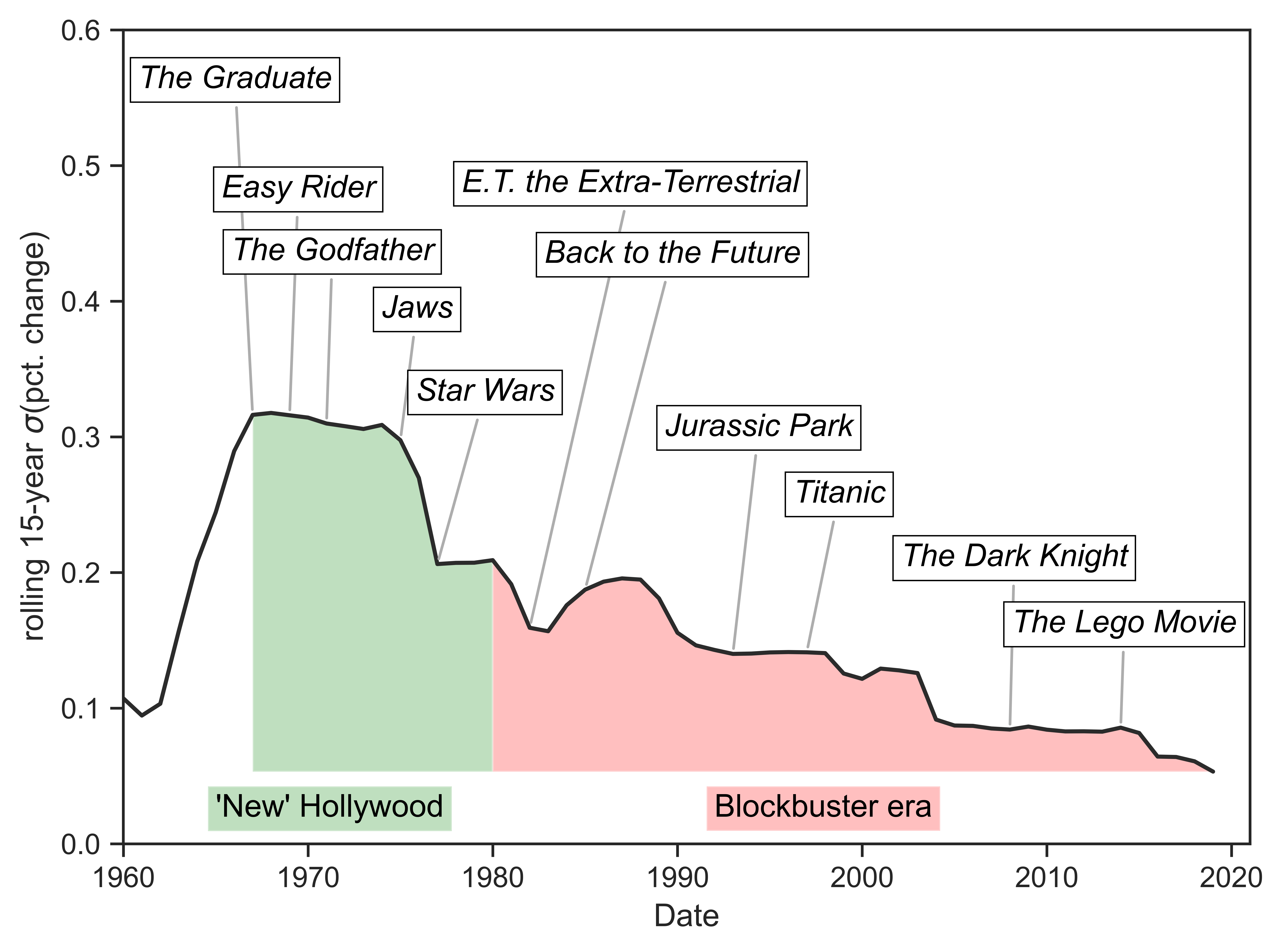

Hollywood’s drive for risk reduction is implied in Figure 5 but clearly found in the long-term reduction of earnings volatility. Figure 6 presents an updated version of my index for the volatility of the earnings per firm of Hollywood’s major studios. The figure is presenting ex post risk. For each year, I compute the percent rate of change of earnings from its five-year trailing average. Second, I measure, for each year, a trailing fifteen-year standard deviation of the computed rates of changes. Thus, the larger the standard deviation, the greater the volatility in the earning growth rates of Hollywood’s previous fifteen years.

With data going into the late 1940s, the time series in Figure 6 confirms that, in terms of profits, the troublesome period was from the late 1960s to the last years of the 1970s, when risk spiked and stayed high. After the 1970s, risk steadily declined and continued to decline to 2019. The level of risk in 2019 is also lowest in the period from 1950 to 2019. The annotations in Figure 6 are meant to remind us of the film history that overlaps this reduction in risk. We might not know the contribution of each film to this decline–and there are many other important films in any story about Hollywood–but the coincidence of a significant reduction of earnings volatility occurring after the twilight of “New” Hollywood is unlikely an to be an accidental one.

Note: Before the percent change is calculated, series is smoothed with a five-year rolling average. Source: Annual reports of Columbia, Paramount, Twentieth Century-Fox, Universal, and Warner Bros. for operating income, 1943-1955. Compustat through WRDS for operating income, 1950-1992. Annual reports of Disney, News Corp, Viacom, Sony, Time Warner (Management’s Discussion of Business Operations for information on their filmed entertainment interests) for operating income of Major Filmed Entertainment, 1993-2019.

TO BE CONTINUED …

Further reading

McMahon, J. (2013). The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema. Review of Capital as Power, 1(1), 23–40.

McMahon, J. (2015). Risk and Capitalist Power: Conceptual Tools to Study the Political Economy of Hollywood. The Political Economy of Communication, 3(2), 28–54.

McMahon, J. (2019). Is Hollywood a risky business? A political economic analysis of risk and creativity. New Political Economy, 24(4), 487 – 509. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1460338

References

Bach, S. (1985). Final Cut: Dreams and Disaster in the Making of Heaven’s Gate. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Bordwell, D. (2006). The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Cook, D. A. (2000). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate, 1970-1979 (C. Harpole, Ed.) (No. 9). New York: C. Scribner.

Finler, J. W. (2003). The Hollywood Story. New York: Wallflower Press.

Kirshner, J. (2012). Hollywood’s Last Golden Age: Politics, Society, and the Seventies Film in America. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Wyatt, J. (1994). High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood. Austin: University of Texas Press.