Corporate Taxation and the Power Theory of Value

May 4, 2016

Sandy Hager

This is a (longer) draft version of an article that is under consideration for the newsletter of the Tax Justice Network: Tax Justice Focus.

Taxation is all about power. We are constantly reminded of this when flipping through any newspaper (or browsing any news website). The Panama Papers, the stuff of which front page headlines are made, provide the names and the numbers to confirm what was already widely understood: that offshore finance exists to help the global elite avoid taxes. Scandalous exposés reveal how G.E. — one of America’s largest companies — makes record profits whilst paying nothing to the U.S. Treasury. Their method? A combination of “innovative” accounting to shift most profits offshore and fierce lobbying for tax breaks in Washington. Google’s sweetheart settlement with HMRC, allowing the company to pay 130 million for ten years of back taxes (an effective tax rate of just three percent), left many wondering where the power to design and enforce tax policy really lies: with politicians or with the corporations themselves?

These examples highlight the intuitive linkages between taxation and power. Yet more systematic research needs to be conducted on the tax strategies of the powerful and the forms of resistance that emerge to challenge them. Systematic research in this area could provide useful insights into what should be done to reform tax policy at the national and global levels. In this piece, I discuss what the power theory of value can tell us about the relationship between power and corporate taxation.

The power theory of value approaches the question of valuation from the top down. In other words, it focuses on the process by which the dominant owners of the bulk of societal wealth (i.e. the top 1% of households and the largest corporations) determine the value of their assets. This process is known as capitalization: the discounting of risk-adjusted future earnings into present value.

For the power theory of value, capitalization is the main ritual, the overriding logic, through which owners understand the world, and the metric through which they measure their performance. The goal of owners is to increase the relative value of their capitalized assets by beating the average rate of return, and thereby increase their share of societal wealth and income. To the extent that owners beat the average they achieve differential accumulation. Power is both the means and ends of differential accumulation. Beating the average requires power (e.g. the power to mould consumer preferences through advertising, the power to lobby government for lax regulation, the power to punish violators of intellectual property rights), and, in turn, beating the average further augments power (e.g. more resources for advertising, lobbying and legal representation).

To understand how all of this relates to corporate taxation, we can start by breaking capitalization into its component parts:

K = E / δ × r

Where capitalization [K] is equal to earnings [E] divided the risk coefficient [?] multiplied by the normal rate of return [r]

As the equation indicates, the earnings that get valued (or capitalized) are future earnings that have not yet been earned. Given that the future is unknowable, owners use past earnings as an anchor, along with the calculable risks that might impact the course of future earnings. Thus forward looking capitalization involves a complex juggling act: owners keep track of past earnings performance, they keep track of what they think will happen in the (unknowable) future, and they keep track of their competitors, to see if they are beating the average rate of return.

Now, the past earnings that serve as a guide within the capitalization formula can also be broken down as follows:

E = R – C

Where earnings [E] are equal to revenues [R] less costs [C]

Tax is a cost of doing business. And all other things being equal, a company that lowers its taxes also boosts its earnings. To the extent that lower taxes result in higher relative earnings, and to the extent that taxes are expected to remain low in the future, a company will boost the relative market value of its shares. How, then, does a company lower its tax burden? As the examples from the introduction to this piece suggest, the ability to decrease taxes is dependent on power. Corporations use their instrumental power — lobbying resources and cozy relationships with politicians — to pressure for changes to the tax regime that work in their favour. Structural power — the latent threat of an ‘investment strike’ or ‘capital flight’ — can also discipline governments to create a tax regime favourable to business. In essence, when it comes to taxation, what gets capitalized are the expectations concerning the corporation’s power to lower its tax burden in the future.

Cutting costs by reducing taxation is, however, a double edged sword. Although an aggressive tax strategy can boost profits and capitalization, it also carries certain ‘reputational risks’. Protests against corporate tax avoidance can lead to boycotts, which lower revenues. If such boycotts are expected to continue to dint a corporation’s revenues in the future, this will negatively impact on its capitalized value. Similarly, policy changes might target tax loopholes. If policy changes are expected to impact the future cost cutting abilities of corporation, this will also have an impact on its capitalized value.

How does this power theory of value actually help us to research corporate taxation? And what can it tell us about limits and possibilities of corporate tax reform? In the remainder of this piece, I discuss a couple of examples of so-called tax inversions that illustrate the “value” of researching corporate taxation from a power perspective.

Tax inversions are a type of merger deal in which a (usually larger) company in a high tax jurisdiction allows itself to be bought by a (usually smaller) company headquartered in a low tax jurisdiction. On paper, the smaller company buys the larger one, but in reality it is the larger company that swallows up the smaller one in order to take advantage of the low tax regime in which the target is headquartered. The end effect is doubly fortuitous for the larger company. Not only does it lower its tax burden, but it also gains access to any cash reserves that it might have stockpiled to avoid the high taxes of their original jurisdiction. Supporters of inversions justify them on the same grounds that they justify ordinary mergers (e.g. exploiting “synergies” and creating economies of scale and scope). But critics view them as little more than a tax dodge, one that consolidates global corporate power through the creation of ever-larger business entities.

Informed by the power theory of value, D.T. Cochrane offers an insightful analysis of Burger King’s inversion deal with Tim Horton’s, which allowed the American fast-food chain to relocate to Canada (where the 15 percent statutory corporate income tax rate is considerably more attractive than the 35 percent rate in the US). From the moment the deal was announced in the summer of 2014, it drew the ire of politicians and activists, who called for a boycott of Burger King in response to its “unpatriotic” tax strategy.

Yet despite the reputational risks, the owners of Burger King were undeterred. Due to the high costs involved, the shares the acquiring company (Burger King) often dip when a merger deal is announced. But as Cochrane’s research shows, the prospect of a lower tax burden was, in this case, enough to allow both companies to achieve differential accumulation. With the announcement, the S&P 500 index stayed flat, while both Burger King and Tim Horton’s experienced a roughly 20 percent rise in their respective market capitalizations. Not only did the inversion deal allow both companies to the beat the average, it also created the world’s third largest fast food conglomeration, further concentrating an already heavily concentrated sector.

This example from the world of fast food illustrates how tax avoidance can help corporations to beat the average and augment their power. But it is important to acknowledge that multinational corporations, although powerful, are not omnipotent. Political action can discourage the most egregious forms of corporate tax avoidance by punishing offenders where it hurts them most: their capitalized bottom line. Evidence of the meaningful effect of such action can be found with the U.S. Treasury Department’s unveiling of new regulations to combat inversions in early April of 2016.

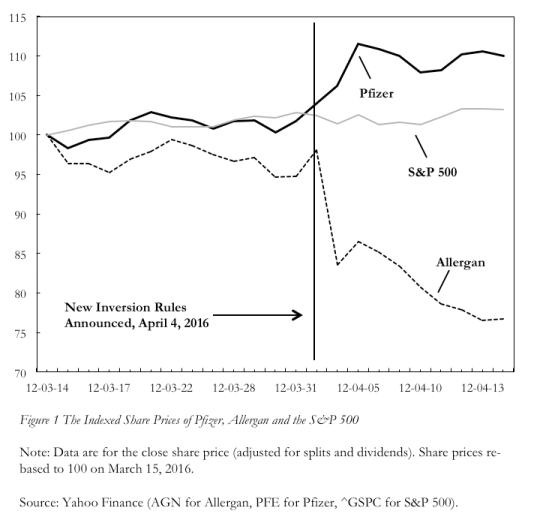

Thanks in large part to sustained pressure from activists, the Obama administration has been trying to tackle tax inversion since 2012. But in April it announced its most ambitious actions yet. These measures were, in large part, implemented in order to prevent American pharmaceutical giant Pfizer from merging with Ireland-based Allergan. In what would have been the largest inversion in history, the deal would have allowed Pfizer to take advantage of 12.5 percent Irish corporate tax rate. As we can see in Figure 1, prior to the rule changes, Pfizer’s shares had been meeting the average, but climbed four percent in the week after the announcement on April 4th. Pfizer’s share price was likely buoyed by the expectation of cost savings due to the collapse of the deal and by the expectation that the company would be able to complete another tax saving deal that got around the new rules in the future.

But for target company, Allergan, the announcement of the new rules to curb tax inversions was nothing short of disastrous. Prior to the rule changes, Allergan’s shares performed slightly below the average, but fell nearly 18 percent in the week after the announcement. The reason for this dramatic decline has to do with the way that the new rules prohibit so-called “serial inverters” such as Allergan — companies that have already completed other inversion deals over the past three years — from completing further inversions. Now labelled a serial inverter, Allergan maxed out its capacity to cut costs through tax avoidance.

As a guide to political action, the power theory of value lends itself to a two pronged approach to corporate tax reform. In the short term, the Allergan case shows that meaningful change can be brought about by working within the logic of the system. Tax shaming, protests, boycotts and rule changes that harm the bottom lines of tax avoiders do indeed discourage the most harmful practices by punishing the offenders at their own game. In long term, however, reform efforts should also aim at challenging the system itself. It is the logic of capitalization and its incessant drive to beat the average that motivates corporate tax avoidance. Is it possible to create an alternative political economic system — including an alternative approach to taxation — that tames or eliminates this drive altogether?