Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

February 16, 2021 at 12:28 pm in reply to: Exchange with Blair Fix on an ecological Kalecki/Goodwin model #245353

To clarify to forum readers, this is an exchange that started via email. Brian asked me the question above, and I responded below. After Brian’s second response (which he will post shortly) I asked him if he’d like to continue the discussion on this forum, so that the back-and-forth would be public, and also so that other people could weigh in if they wish.

Hi Brian,

Thanks for getting in touch. About heterodox economics and biophysical economics, you are correct that there is a disconnect. I am increasingly convinced, however, that the way to solve this is not by ‘speaking the language’ of economics to heterodox economists. That’s because I think that almost everything about economic growth theory (including heterodox approaches) goes down the wrong path. (Obviously, many people don’t agree with me on this).

The problem is that the goal, in economic growth theory, is to explain the growth of real GDP. Even heterodox economists, who are generally skeptical of neoclassical theory, mostly agree on this goal.

In contrast, I think real GDP is a garbage indicator. Hence it’s growth is not worth explaining. (See this post for details: https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/2019/04/29/real-gdp-the-flawed-metric-at-the-heart-of-macroeconomics/). When we throw out real GDP (and the concept of ‘economic output’), that leaves models of economic growth (Solow, Goodwin, etc) with nothing to do. So there is virtually nothing left of economic growth theory.

The solution is to turn not to economics, but to biology. Ecologists and biologists study the growth of natural systems all the time. They never use production functions. They never measure ‘output’. Instead, they study biophysical flows. It’s these flows that are important in their own right. We should study them directly, and how they relate to social structure.

Yes, it may be politically easier to get heterodox economists on board with thermodynamic limits by evoking their models. But I think the result is bad science. On that front, I’d rather have good science that is politically naive, in the sense that most economists will ignore it.

That said, there are economists doing good work. Some of the most interesting stuff (that’s heavily influenced my thinking) is work by Giampietro, Mayumi and Sorman. They have written two books about the role of energy in human societies. They do not use production functions, nor indeed anything recognizable from economic theory. Instead, they’re influenced by ecology. The books

- The Metabolic Pattern of Societies: Where Economists Fall Short

- Energy Analysis for a Sustainable Future: Multi-Scale Integrated Analysis of Societal and Ecosystem Metabolism

To drill down to the point, you ask:

do you think there can be a Kaleckian or a Goodwin model that accounts for energy and natural resources – or that treats them as “factors of production” – and explain the determination of aggregate demand and income distribution?

My answer is no. I think these models are dead ends. But if you think otherwise, I would encourage you to explore your ideas.

Hope this helps.

Blair

- This reply was modified 4 years, 10 months ago by Blair Fix.

February 16, 2021 at 9:40 am in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245347Hi David,

I have always interpreted Munford’s idea of the ‘mega-machine’ as a metaphor, not to be taken too literally. That said, I agree with Scott that if you do want to take it literally, then you should interpret the word ‘machine’ in a biological sense.

All living things are essentially robots — bits of matter that have become animated. None of the fundamental constituents (molecules and atoms) have any agency. Nonetheless, through the miracle of complexity, matter somehow organizes into forms that at least appear (to us) to have agency.

What may interest you is something called a ‘major evolutionary transition’. This happens when a whole new level of natural selection emerges. Life started as replicating molecules, that then organized into larger proteins (RNA), that then organized into prokaryotic cells, that then merged into eukaryotic cells, that then organized into multicellular organisms, that then grouped into eusocial animals …

At least in the context of human evolution, the emergence of civilization counts as a major evolutionary transition. We went from being a social primate to being ‘ultrasocial’.

Enter Mumford’s ‘megamachine’. The emergence of civilization went hand in hand with the concentration of power. Humans, for the first time, organized in large-scale hierarchies. If you want to frame this transition in terms of evolutionary theory, then it’s just part of a longer story. With every major transition, units that were previously ‘autonomous’ became cogs in the emergent larger ‘machine’. But in a strict scientific sense, it’s still ‘machines all the way down’. There is no unit where you can distinguish between ‘living’ matter and ‘dead’ matter. It’s all just matter.

One last point. You write that you are interested in state theory. I am not an expert on the literature at all … mostly because I find it impossible to understand. My impression (and others can correct me) is that much of state theory seems to a dive into the bowels of Marxist theory with little connection to science (i.e. empirical evidence).

The problem, in my view, starts with the word ‘state’ itself. Most lay people have no idea what it means. But if you use the word ‘government’, they suddenly understand. I may be wrong, but I can’t see how the ‘state’ is any different than ‘government’. It’s just one form of organized power. D.T. Cochrane has been tweeting about this lately, so perhaps he can add more.

Adam, I think your charts provide a good illustration of log vs linear scales. On the linear scale, what stands out are the two bumps in differential capitalization — one in 2013 and one in 2018. The log scale, in contrast, emphasizes the long-term downward trend.

Something to note. You can emphasize this downward trend by changing the limits of your y axis. Right now, excel is using a scale from 1 to 1000. But the data never gets close to either of those extremes. Have a look at the min/max values of your data and then limit the scale appropriately. This will make the log-scale graph look better.

One last trick. When you’re using a log scale that varies over only a few orders of magnitude, showing only factors of 10 (on the axis) leaves a lot of blank space. I find factors of 1, 2, 5, 10 fill in the space nicely. See the chart below for an example.

Fascinating results. I would personally use both series. As James says, the results for either denominators are more or less the same. That’s actually important to show.

Also something to think about. See what the data looks like using a log scale on the vertical axis. This will ‘zoom’ in on the recent collapse in differential capitalization. On a linear scale, a collapse in differential capitalization looks like a flat line at y = 0. But on a log scale, the line will head south forever.

Use the scale that best tells the story you want to highlight.

February 5, 2021 at 2:10 pm in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245280I have posted Tim Di Muzio’s commentary on the GameStop phenomenon. Worth a read:

GameStop Capitalism: Wall Street vs. The Reddit Rally (Part 1)

February 2, 2021 at 2:08 pm in reply to: Dominant Capital is Much More Powerful Than You Think #245263Thanks for this update, Shimshon and Jonathan. I wonder how changing the denominator might affect what we find. You compare the profits of dominant capital to the average profit of all US corporations. This is fair, but it masks an important trend.

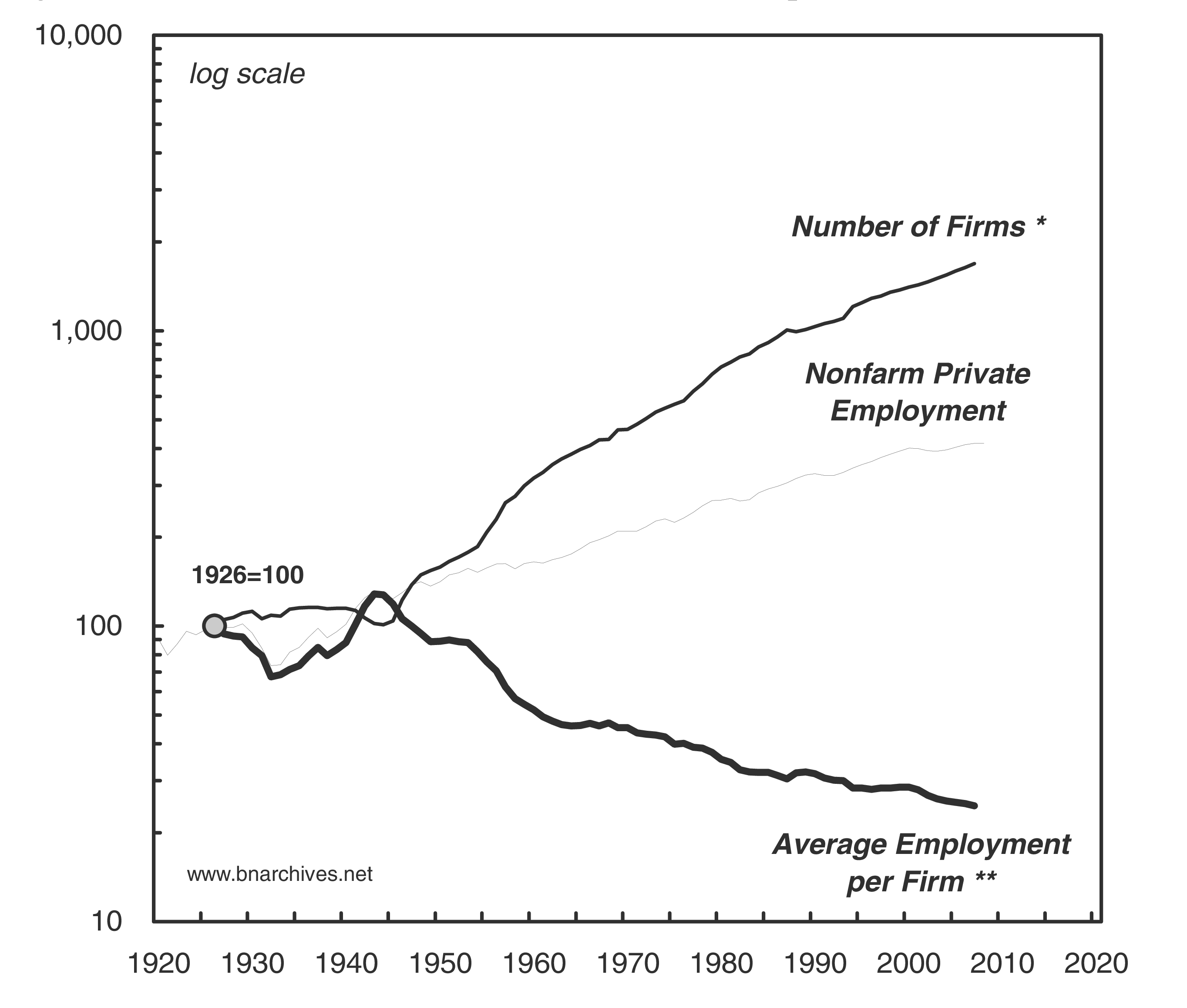

In the 20th century, in addition to the trend towards corporate bigness, there was a trend towards more businesses incorporating, rather than operating as proprietorships. This trend tended to make corporations smaller. That’s what you found in the figure below, taken from Capital as Power

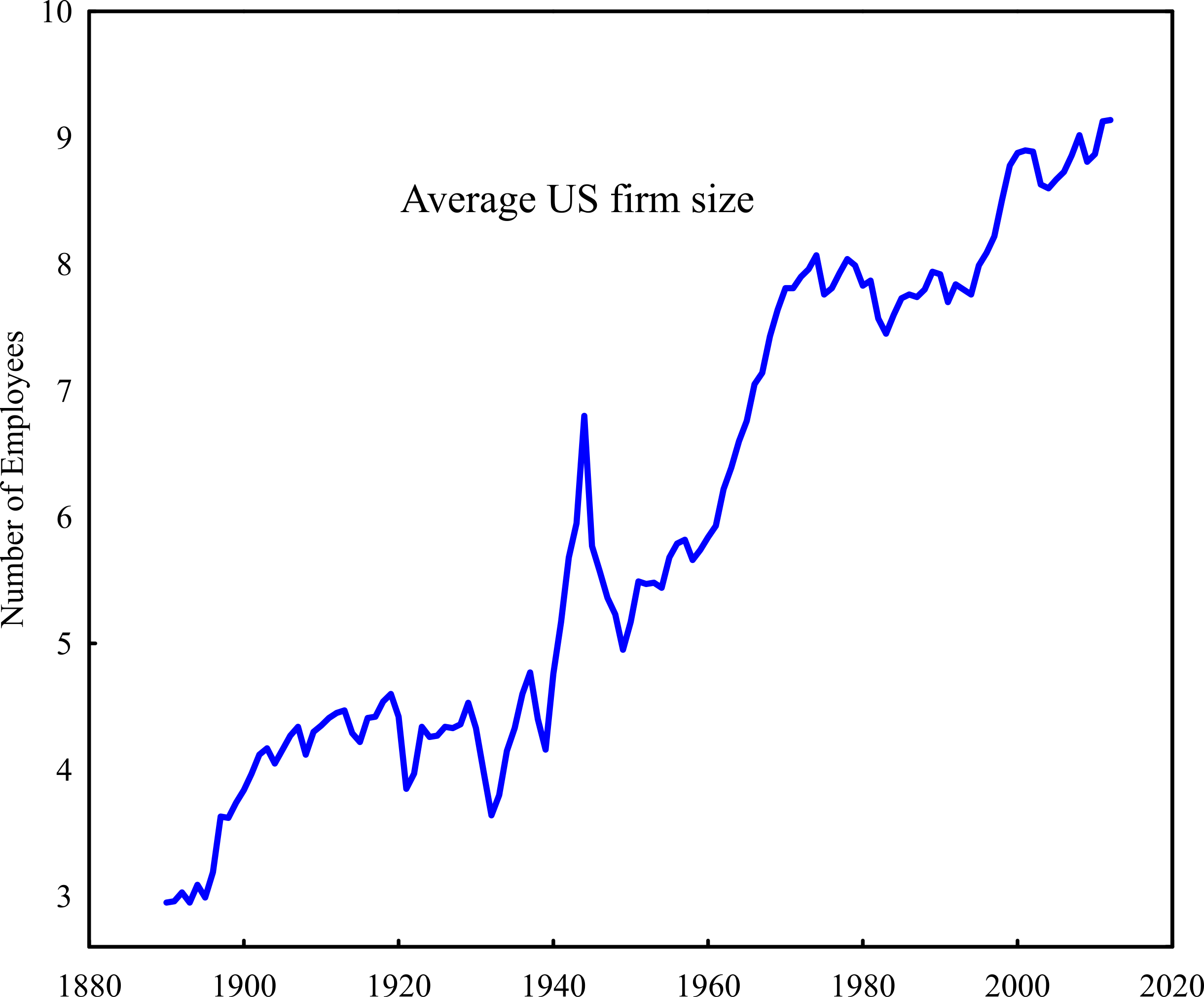

In my own research, I’ve looked at the same trend, but instead of looking only at the size of corporations, included also the size of proprietorships. When I do that, I find a very different trend — not towards smaller firms, but bigger firms.

Both results are ‘correct’, but they measure different things. I wonder, instead of comparing the profits of dominant capital to the average profits of all corporations, what would we find if we included proprietorships in the denominator. Then we’d be mixing income types (profit and proprietor income). But the reasoning is that, whether incorporated or not, small businesses are competing with dominant firms. I wonder how the trend might change?

I conquer. Very glad that you’re jumping in the quantitative water and interested to see what you find.

January 29, 2021 at 2:17 pm in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245235I just have time for a quick comment.

1. Calling the stock market ‘fake’ or ‘fictitious’ is a big mistake, because fake things aren’t supposed to impact the real world. And yet the stock market hugely impacts the social order.

2. I am still trying to come to grips with the recent events you mention. The best take I’ve read so far is by Cory Doctorow: https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/28/payment-for-order-flow/#wallstreetbets

Doctorow is a sci-fi fiction writer by trade, but offers very insightful commentary on political economy. I recommend following his blog.

3. I agree that we must ultimately abolish the stock market and replace it with a more democratic form of organizing. But I have no idea what that would look like.

I agree with DTC here that the basics of CasP research (differential capitalization) are quite simple. When I started to do this type of work, it was revelatory.

I also remember the panic I felt when I tried to fit too much quantitative work into my master’s thesis. I didn’t have the time to do it right, or interpret the results to my satisfaction. I ended up getting the thesis done. But my mental health suffered.

Now that I know what I’m doing, I can usually churn out quantitative analysis on a tight deadline. But that’s because I’ve got the learning curve out of the way. The last thing you want is to be dealing with both a tight deadline and a steep learning curve.

Something else to consider. Sometimes, as in James’ example, the webpage is served in html. That’s easy to scrape. Other times, however, the server just provides javascript code, which your browser then renders. If you want to scrape that, you need to have software that renders the javascript to give you the ‘inner’ html. I use the Selenium Webdriver in python.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 12 months ago by Blair Fix.

I too have been webscraping recently. I’m working on a project that involves mass downloads from Library Genesis. The tricky part is that their server(s) are unreliable and downloads sometimes fail.

I’m currently using R to execute the Linux command wget. I have it keep a log for each file. I have a script that then reviews the logs and retries any downloads that failed.

My code works, but it’s not very clean. I’m looking for a better alternative.

Side note: The Library Genesis server is slow, so scraping more than a few thousand books is not really an option.

Hi Adam,

Here’s my two cents.

First, empirical work is slow going, especially if you’re new to it. You need to find the data, learn how to use it. And if you’re completely new to empirical work, learn the basics of data analysis. These are all things that take time to learn and you do not want to rush. If you had lots of experience, I’d say 2-3 months is lots of time. But since it sounds like you’re new to quantitative work, that’s very little time. You also have to keep in mind that you might not find what you wanted (i.e. the empirical evidence may contradict the arguments you’re making).

For all of these reasons, my gut feeling is that trying to do good-quality empirical work for your PhD thesis will take more time than you have. It may be better to delay this work for when you publish your PhD research. Then you can take the time you need.

I’m curious what other CasP researchers think.

Blair

Devil’s advocate: The total return to the S&P 500 is a theoretical construct in the sense that no individual actually earns this indexed value. To do so, they’d have to own exactly the stock that the S&P was composed of. With modern ETFs, that’s easy. A century ago, it was not.

More problematic, though, is that few capitalists perpetually reinvest their dividends. And as people die, their fortunes tend to be disperse among many decedents.

My point is that this comparison of stock market total returns to wages paints a picture of runaway income inequality — something that hasn’t actually happened. Many people earn close to the average wage (over time). But few people (if anyone) earns the actual S&P total return.

Thoughts?

December 4, 2020 at 1:14 pm in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #245107Thank-you, Jeremy, for you well-thought-out response to my work. I accept most of your arguments, so I’ll use this response to outline some related ideas.

As I’ve started to popularize my research on hierarchy, a common response (by those who are skeptical of it) is that hierarchical rank simply indicates skill. People with more skill are rewarded with a promotion, where they then earn more income. I’ve had some time to think about it, and I’ve realized that this thinking ties into deep-seated ideas about meritocracy.

To get started, let’s formalize this meritocracy reasoning using a causal diagram:

skills ⟶ hierarchical rank ⟶ income

Skills cause (greater) hierarchical rank, which then causes (greater) income. So on it’s own, skill does not cause income. Instead, skill must be ‘realized’ though a promotion.

I agree that my ‘timing’ argument does not dispel this meritocracy model. Skills can build slowly and then be rewarded suddenly with a promotion. As long as ‘skills’ are the criteria for promotion, people can claim that ‘skill caused income’.

In a sense, they are right. If we take the ‘meritocratic’ corporate hierarchy for granted, then gaining ‘skill’ is the path to earning more money. Or at least, gaining the credentials that people think indicate skill is the path to earning more money. Hence the need to get an MBA to get into management. Never mind what you actually learned in your MBA …

For many people, this thinking is enough to satisfy their curiosity. It tells them "if you want more money, do x." But from a scientific standpoint, it’s unsatisfying. It doesn’t tell us why skill (however defined) can only be transformed into income when it is ‘realized’ by a promotion. Which brings us back to hierarchy.

Here you raise an excellent point:

… the ultimate decisions about that individual’s skills and position are made on the terms established by the corporation—or more specifically, the corporation’s hierarchy.

As soon as we think this way, the idea of ‘skills causing income’ gets hopelessly muddied. I’ve lamented on my blog that many social scientists don’t understand causation, and I think this is worth restating. Many social scientists are trained in the tradition of methodological individualism, in which a ‘cause’ must ultimately be attributed to a trait of the individual. That ‘causes’ can be social does not compute.

As you point out, it is the hierarchy that decides which traits get rewarded and which do not. In a feudal society, the hierarchy rewards birthright. In a ‘meritocratic’ society, the hierarchy rewards ‘merit’. But as you point out (and as I’ve explored here), not every trait is rewarded with a corporate promotion. Only those skills that are deemed valuable to the corporation are rewarded.

The problem is that once we admit that the social environment is itself a cause of income, then things get really complicated. What caused the social environment? Where did the belief in birthright come from? Where did the corporate belief in ‘merit’ come from?

Thinking about these questions is where the methodology of economics completely fails us. Take the current obsession with randomized experiments. Imagine we take one group of people and give them a Harvard education. Take another group and give them a community-college education. Which group earns more income? The Harvard group, obviously. Conclusive proof, the randomistas would say, that skill causes income.

Now imagine trying to test the effect of the social environment. Now you have to take a group of people and put them into different societies. One group goes to a hunter-gather society with no hierarchy. Another group goes to a feudal society where rank is awarded by birthright. And a final group goes to a corporate ‘meritocracy’. It’s a fun experiment to think about, but one that is impossible to implement.

Still, I think about this experiment a lot because it is useful for understanding causation. In his Book of Why, Judea Pearl defines ‘cause’ in counterfactual terms. If x causes y, then taking away x removes the effect y.

With this definition in mind, let’s go back to our meritocracy model:

skills ⟶ hierarchical rank ⟶ income

Understanding the causal role of hierarchy rank in determining income requires taking away hierarchy. In other words, in a world without hierarchy, you can observe what statisticians call the ‘direct’ effect of skill on income:

skills ⟶ income

The funny thing is that societies that lack hierarchy also lack any significant form of inequality. So the direct effect of skill on income is … nil. Not really surprising. The reward to any human trait is mediated by our social environment … so it’s ‘direct effect’ is nil.

I’ll close by returning to the idea of ‘hidden skill’. My research shows that no personal trait (with available data) affects income as strongly as hierarchical rank. The reason, I believe, is quite simple: there are many paths to hierarchical advancement. Maybe you inherited a business from your parents. Presto — rank by birthright. Maybe you live in a racist society. Presto — rank by race. Maybe you live in a society that worships ‘intelligence’. Presto — rank by IQ score.

Many different traits are rewarded with advancement. And that’s why no individual trait predicts income as strongly as hierarchical rank. That’s because no individual trait perfectly predicts hierarchical advancement.

But imagine that there was such a skill. Although unobservable, this skill perfectly predicts hierarchical rank, and this ‘explains’ the returns to hierarchical rank.

I’ll call this the ‘dark matter’ argument. In cosmology, ‘dark matter’ is inserted anywhere that the Newtonian theory of gravity fails. In our theory of income distribution, ‘hidden skills’ are our dark matter. We insert them where ever observable skills don’t explain income (as well as hierarchical rank does).

You’re quite right that my argument about a ‘timing mismatch’ doesn’t dispel this argument. I think that the strongest critique is that the hidden skill hypothesis simply isn’t science. It’s irrefutable … hence garbage.

That said, I think we both agree that we shouldn’t dismiss ‘skills’ as a pathway to hierarchical advancement. I would love to see research about how the beliefs and attitudes of corporate brass affect the traits that are (or are not) rewarded in the corporate hierarchy. We need a modern-day Veblen to write a ‘Theory of the corporate class’.

November 22, 2020 at 9:23 am in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #4533A quick note, Jeremy, to say that your comments are well received. They highlight many of the problems of understanding causation in a social environment, and are worth a detailed reply. I hope to have one by next week.

-

AuthorReplies