Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

February 9, 2022 at 8:20 pm in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247787

If I understand correctly, CasP implies that capitalization (discounted future earnings) is power so a decline in this, which would happen in a stock market crash, is a positive outcome.

I am not sure how you get from “capital is power” to “stock market crash good.” Seeking to understand capital as a mode of power does not require animosity towards power. Indeed, one of the knocks on CasP is that CasP doesn’t attempt to suggest to us what can/should be done with its conclusions; i.e., CasP lacks praxis. See, Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

I offered up Tim DiMuzio’s Debt as Power because it is the only example of a CasP researcher proposing solutions (twelve of them, of which the debt strike is but one means to implement those solutions) of which I am aware.

February 8, 2022 at 8:09 pm in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247759Here is a link to what appears to be a good resource on the rise of the semiconductor foundry and fabless business model.

February 8, 2022 at 7:48 pm in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247758It is worth noting that in most cases ‘capacity’ measures refer to the maximum volume that businesses think they can produce profitably. In a minority of cases, when business surveys are not available, the statisticians simply connect production peaks and interpret the interpolation (or extrapolation) as capacity. These methods mean that published capacity is not the technical maximum, but the business maximum — either in the mind of managers, or based on the interpolated/extrapolated history of business production.

That’s right. For example, large semiconductor companies like Intel and Samsung typically target a minimum of around 85% fab utilization, assuming 15% downtime for maintenance, etc.. One of the reasons why these companies are starting to offer foundry services is they cannot reach 85% utilization of the new fabs they are building, if they only make their own products.

February 8, 2022 at 7:31 pm in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247757Thanks Scot, You articulated much more clearly one of my guesses, namely that high fixed costs of fabs eat into operating margins when production is slow. But there are still at least two puzzles for me. First, why such a tight correlation? I’ve looked at a few other sectors and so far I haven’t found much if any correlation between these two variables. Second, if its just an accounting issue, what happened after 2007?

Interesting questions. I would argue there are two primary factors driving the correlation (or lack thereof): (1) the rise of the fabless and fab-lite semiconductor business models; and (2) the shift in the semiconductor industry’s focus from personal computing to wireless, especially smart phones.

First, fabless companies do not bear the risk of underutilization, their foundry partners do. Similarly, fab-lite companies have reduced risk and typically manage that by only keeping fabs they can run at near 100% capacity (at Spansion in the early 2010s, we averaged 95% utilization in our legacy fab). In the 80s and 90s, most large semiconductor companies were IDMs (integrated device manufacturers) who made all their own chips (or even provided foundry services), and they did not use foundries. This changed over time, and today only 2 of the top 10 semiconductor companies make all their own chips (5 are fabless, 1 is fab-lite, and two are IDMs who are significant foundry customers).

Second, as PCs became less important and wireless/mobile became more important, many fabless companies became industry leaders, and even large IDMs like Intel were forced to make competing chips in foundries, often because to compete in the new area they acquired companies that were fabless.

So, when most semiconductor companies made almost everything they sold, you had a tight correlation. As the semiconductor industry increasingly outsourced manufacturing to foundries (due to a combination of the economics of fabs and a change in product mix), the correlation disappeared.

Fabless and Fab-Lite

TSMC, which currently has over 50% of the foundry market, was founded in 1987 to provide contract semiconductor manufacturing services. Originally, most of their customers were companies like IBM, GM, etc. who designed their own chips but didn’t want or have the ability to make the chips themselves. Over time, especially with the success of PC in the early 90s, you saw a lot of specialty chip companies adopting a fabless model. Nvidia, for example, was founded in the early 1990s by former engineers at Sun Microsystems who wanted to make a single-chip multimedia (graphics, video and audio) chip for PCs and gaming consoles. (They could never get the multimedia chip to work, so they stuck with just the graphics, which is what the founders really knew how to do well.)

Starting around 2000 a lot of IDMs decided to stop building new fabs and/or to divest themselves of existing fabs to go fabless or fab-lite. These decisions were typically announced around the time companies had to decide whether to invest in the next node of lithography. A few dropped out at the 90nm node, more at the 65nm node, and a lot more at 45nm. AMD, whose original CEO claimed “Real men have fabs,” went fabless in 2008-9 (near the 45nm node), spinning out Global Foundries and letting it invest in 32nm instead. A prior AMD spinout, Spansion, which I later worked at, went fab-lite in 2010 (we had a fully depreciated fab in Austin, TX, doing primarily legacy stuff at >90% capacity, and all the new stuff went through foundries in Taiwan and China).

Today, even the largest IDMs are big foundry customers. Indeed, Intel, who was number 2 in semiconductor sales in 2021, is TSMC’s largest customer (and it has its own foundry business, too).

Of the top 10 semi companies in 2021, 5 are fabless (Qualcomm, Nvidia, AMD, MediaTek and Broadcom), 1 is fab-lite (TI stopped making their own chips at 45nm) and 2 are big foundry customers (Intel and Samsung). Only the pure-play memory (DRAM and flash) makers like Micron and SK Hynix (who round out the top 10) remain IDMs, and that is only because they don’t have any margin to share with foundries.

The move towards fabless has been accompanied by a lot of industry consolidation, as well. Shortly after I left Spansion in 2014 (after we acquired a division of Fujitsu), Cypress acquired it, and last year Infineon acquired Cypress. So you have fewer companies selling chips, and more chips being made by foundries.

Shift from PC to Wireless

In the 1980s and 1990s, the PC drove semiconductor sales, especially for microprocessors and DRAM (system memory). Flash memory was just being introduced in the 1980s (I was at Intel as a co-op engineer in 1987 when they taped out their first NOR flash product), and did not find much use in the PC until recently (SSDs were being invented in the early 1990s, but did not see production until the 2010s).

Everything started to shift in the mid-2000s with the rise of affordable cellular phones and other mobile devices. Then Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007 and the iPad in 2010. By then, PC industry growth had slowed (if not started dropping), so wireless became the semiconductor industry’s driver, changing the pecking order of the industry as a whole, with many of the most prominent fabless companies rising to the top 10 in sales (what had been specialty products like baseband processors were now mainstream, high volume runners) and a lot of old line top semiconductor companies (like Toshiba, Fujitsu and Sony) focusing on internal customers, dropping out of the top 10 (or even top 20).

February 8, 2022 at 12:25 pm in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247754I think the correlation is due to accounting rules.

Regardless of utilization, running a fab involves fixed costs and variable costs (together, the cost of goods sold) and depreciation (which hits the operating margin, not the gross margin). When you budget for 85% utilization, your fixed costs are equal to what it costs to run the fab at 85% utilization. So, if you are actually running at 65% utilization, your fixed costs are spread out over 20% fewer units, decreasing the gross margin. Depreciation does not depend on utilization, so you are spreading 100% of depreciation over 65% of the maximum number of units, reducing your operating margins.

When I was at Intel (20 years ago), I heard that utilization below a certain threshold can result in the acceleration of depreciation that would further squeeze margins in the quarter the write down occurs, but I can’t recall if that kind of write down is triggered by a single quarter or multiple quarters below the threshold. I think this kind of accounting rule depends in part on utilization history. A new fab, for example, can’t be expected to immediately be at 85% utilization.

See this risk factor from Intel’s most recent 10-K, which discusses the accounting consequences of underutilization:

Due to the complexity of our manufacturing operations, we are not always able to timely respond to fluctuations in demand and we may incur significant charges and costs. Because we own and operate high-tech fabrication facilities, our operations have high costs that are fixed or difficult to reduce in the short term, including our costs related to utilization of existing facilities, facility construction and equipment, R&D, and the employment and training of a highly skilled workforce. To the extent product demand decreases or we fail to forecast demand accurately, we could be required to write off inventory or record excess capacity charges, which would lower our gross margin. To the extent the demand decrease is prolonged, our manufacturing or assembly and test capacity could be underutilized, and we may be required to write down our long-lived assets, which would increase our expenses. We may also be required to shorten the useful lives of under-used facilities and equipment and accelerate depreciation. As we make substantial investments in increasing our manufacturing capacity as part of our IDM 2.0 strategy, these underutilization risks may be heightened. Conversely, at times demand increases or we fail to forecast accurately or produce the mix of products demanded. To the extent we are unable to add capacity or increase production fast enough, we are at times required to make production decisions and/or are unable to fully meet market demand, which can result in a loss of revenue opportunities or market share, legal claims, and/or damage to customer relationships.

February 7, 2022 at 5:33 pm in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247752Chapter 5 of Tim Di Muzio’s and Richard Robbins’ Debt as Power offers ideas on how to change/improve things centered around reforming our monetary system to eliminate debt-based money (aka credit money). See beginning at page 135 of the pdf (125 of the document): https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/509/

Also, Di Muzio’s The Tragedy of Human Development: A Genealogy of Capital as Power builds on the analysis of Debt as Power and explores how and why the logic of differential accumulation is fundamentally at odds with humanity itself. The book is available online at places like Amazon, but the table of contents and foreword are available here: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/530/

One thing to keep in mind is that CasP seeks to understand and explain the behavior of dominant capital, not the behavior of individual capitalists/investors. There are similarities, e.g., the drive for differential accumulation, but they are not the same.

Seems like the data is fuzzy with regard to the prevalance of dividend payments. If we assumed that corporations do redistribute their profits as dividends, would that be enough to cast doubt on Ciepely’s thesis?

No. If corporations distributed all of their un-invested profits as dividends, that would simulate actual ownership, but issuing dividends is a discretionary act of the board of directors and management.

What other rights/benefits do shareholders not receive which prevent them from being considered owners?

Shareholders can sell their shares and therefore have the right to alienate and by using votes, have the right to control the company’s assets. It seems to me that the bottom line is that between them, shareholders and managers enjoy the full bundle of rights to a company and i’d argue that shareholders still enjoy the lion’s share of those rights even though many may choose to not exercise their rights due to disinterest or trust in the managers appointed

Shareholders lack the control necessary to be considered owners of the corporation itself. Simply put, they do not control, nor do they have the right to control, the corporation, its managers or its assets, by vote or otherwise. That’s the job of the board of directors.

Shareholders are allowed to vote at the annual shareholder meeting, but the board generally determines what items/issues are up for a vote. Shareholders can place their own proposals to be added to the proxy and put up for shareholder vote, if they do so within the time and manner specified by law. Of course, the board controls the printing and presentation of the proxy and is free to oppose any shareholder proposals. (By the way, shareholder proposals are rare, but see the latest Apple proxy statement.)

The most aggressive shareholder proposals involve trying to replace current board members with their own candidates. This is called a proxy fight. Typically, though, corporations have staggered boards or have other mechanisms in place to ensure that only a minority of board seats are open any given year, e.g., a 9-member board will only have 3 seats open each year. So, even if you as a shareholder get your members elected to the board, they’re still in the minority. Boards typically act unanimously (you never see a dissenting vote in board minutes) and won’t put anything up for a vote that has not been informally agreed. Thus, minority board members have a kind of veto power that potentially allows them gum up the works, but it is in their interest to go along on most things. For their hot-button issues, they need to convince the other board members to vote with them.

Large shareholders do have a voice and many of them seek and receive access to top management, often on a quarterly basis after an earnings call. Shareholders in growth companies don’t want or expect dividends because they want the money to be invested in creating earnings growth. If growth slows and a company is sitting on a lot of cash, I am sure large shareholders will ask about dividends (I’ve heard them ask for share buybacks, for example).

Board approval is (theoretically) required before stocks can be issued and if board members represent shareholders, then this gives shareholders a de facto right to exclude others from ownership.

Publicly traded companies rarely issue new stock after their initial public offering, except as part of employee compensation as stock options and restricted shares. Thus, virtually all of the shares traded on a stock exchange every day are already existing shares.

The only way the board of a publicly traded company could prevent shares from being traded on a stock exchange is by voluntarily delisting the company, which is rarely done (and typically only if the board believes the company is undervalued). The whole point of taking a company public is to allow current shareholders to sell their shares to new shareholders. By delisting the company, you get rid of all liquidity for the stock, effectively reducing its value substantially (because there is no longer an objective market value for the shares).

February 1, 2022 at 11:07 pm in reply to: Does CasP Really Have a Theory of Value? Does It Need One? #247698SC’s reign was short, just 40 years (ca. 1945-1985). SC has nothing to do with Alger. SC and SP are hypothetical types of business culture is a very simply cultural evolution model intended to explain how inequality (measured as top 1% income share) varies over time. Inequality is seen as a proxy for the relative amount of SP vs SC culture present at any time. Since 1916 the business economic environment has changed dramatic as shown by things like top income tax rate, which has varied between 24% and 91% since 1916. There were long stretches of time when stock buybacks with illegal and times when it was perfectly acceptable. There were times with low real interest rates and times with high rates. There were times of strong labor power (measured by strike frequency) and times with weak labor power. These environmental changes affect which type of business strategies are more likely to lead to success, and how success is translated into symbolic markers of prestige, thus leading to their emulation by other businesspersons. Emulation means the spread of the meme being emulated, which is akin to “fitness” in conventional biological evolution.

I assumed your “SC” referred to the first two-thirds of the 19th century, before the rise of trusts and monopoly capitalism. Now that I understand you place SC in an era that was the direct product of the New Deal, I view SC itself as a product of the New Deal, i.e., SC was the product of government-imposed restrictions on the rapacious nature of capitalism. As history shows us, capitalists rebelled against these restrictions and ultimately threw them off. Thus, SC is an aberration.

I do not see how or why capitalism and the liberal creed would have any connection. It seems to me that it is perfectly possible to have one without the other. China, Vietnam, and if one accepts the idea that the USSR was actually state capitalism, are examples of capitalism w/o liberalism. True socialism is presented as a system with liberalism but w/o capitalism.

Capitalism and liberalism were fraternal twins that gestated together in 17th and 18th century England and emerged fully grown around the same time in the 19th century Europe more broadly (before that you had mercantilism and a much more radical, revolutionary version of proto-liberalism). Classical and neoclassical economics are all about equating capitalism with liberalism, which is why these economic theories talk about free markets and use counter-factual constructs such as the “laws of supply and demand” to “demonstrate” the absence of coercive power in the market. Similarly, Locke’s philosophy is also used to equate capitalism and liberalism.

I do not believe that there is some elite conspiracy where they are oppressing everyone. They are as clueless as our foreign and economic elites, but since they wield great power, they can (and actually do) cause much harm.

I do not believe that there is an elite conspiracy, either. But when Congress passes a law that helps a handful of people and harms millions, we don’t call that a conspiracy, do we? No, we call it legislating. Capitalism as we have it today was the result of a struggle among elites who decided upon a solution that requires the masses to pay for it.

As to whether the elites are “clueless,” how do you judge that? Perhaps they operate using a different set of metrics than you do because their goals are not the same as yours. Do we have any basis for believing our elites care about anybody but themselves, that there is an ounce of altruism in any of them?

In my book I try to present an explanation for how we have come to where we are, how we successfully navigated this sort of crisis last time, and provide some ideas on who we might be able to do it a second time. People sense America is in decline, our civilization is falling. Civilizations fall because their leaders engage in folly. Folly is when decision makers operate in what they perceive as their short term self-interest, that ends up producing a very different outcome.

Over the last decade, we have seen an increase in anti-liberal (e.g., alt-right) and “post-liberal” rhetoric and action, which has given rise to leaders like Orban and Trump. To me, capitalism is the cause of everything these “post-liberals” complain about, but they claim to embrace capitalism while rejecting liberalism (i.e., individual rights, personal liberty, equal justice, etc.). FDR and the New Deal navigated this “sort of crisis” by constraining capitalism so that capitalism could survive. Today’s solutions require reinventing capitalism so liberalism can survive, which requires entirely new thinking.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Scot Griffin.

January 30, 2022 at 9:55 pm in reply to: Does CasP Really Have a Theory of Value? Does It Need One? #247694In the beginning, capitalism resulted in output growth because the would-be capitalist needed to exploit some market that had not yet been fully exploited. This results in new or expanded products or services, resulting in more division of labor. For example the voyages of exploration were partly about finding products to sell at home. At first, Columbus and de Gama seeking a source of pepper, a product for which unmet demand existed. Over time, a number of recreation drugs: sugar, tobacco, rum, tea, coffee, were developed, all of which were new products to be produced alongside the existing industries. Besides traveling overseas in search of new markets to exploit, entrepreneurs also sought to develop new products, or ways to produce existing things more efficiently, to produce industry that when harnessed to a business, generated profit. Entrepreneurs could acquire patents granting them monopoly rights over this created industry. Queen Elizabeth issued 55 patents over her reign, showing that some of this sort of activity was happening already in the 16th century, although there was significant cronyism and corrupt practices involved as well. Things became more regularized after 1623 and the rate of useful inventions creating new economic activities accelerated: eyeballing a list in wikipedia and counting what seem to be commercial (as opposed to scientific) inventions I see 1 invention in 16th cent 2nd half 2 inventions in 17th C 1st half 3 inventions in 17th C 2nd half 5 inventions in 18th C 1st half 11 inventions in 18th C 2nd half … and so on. This quickening of invention/entrepreneurship is the beginning of capitalism. The merger of natural philosophy and technology created modern science. Thus the emergence of capitalist is intertwined with the scientific revolution. The industrial revolution is the child of this early entreprenarial/scientific activity. Not all kinds of capitalism result in expanded output. The forms of capitalism that see capital as something real do this. Among these are early capitalism and what is sometimes called stakeholder capitalism (SC). The shareholder primacy (SP) form of capitalism sees capital as purely financial. I suspect that the CasP view of capital as power reflects SP capitalism, which is largely what we have now. How SC and SP evolving into each other is described in chapter 3 of my book. With SP capitalist, output is uncoupled from the operation of capitalism. I never really thought of what the operation of SP capitalism entails, but capitalism as a mode of power (or mind-fuckery for that matter) kinda hits the nail in the head. Marx conceived of capital the way he did because his initial take as a young man in the 1840’s was still during the early period of capitalism when it did involve output increases. Since humans provided the “life force” of economic production all output came from labor, as magnified by accumulated previous labor (i.e. capital), it was labor all the way down according to Marx. OTOH, CasP was developed at a time when capitalism was mostly SP, which would be defined in financial terms (see chapter 4 for the link between business culture and finance). https://mikebert.neocities.org/America-in-crisis.pdf

Capitalism existed at least a century before the Industrial Revolution, and some (not I) would argue that it dates back at least two centuries earlier than that in the agrarian English economy. Capitalism did not complete its conquest of the Western world until at least the late 19th century with the rise of the limited liability corporation (and in the US, a little later). Stakeholder capitalism (SC) seems mythical to me, fed by Horatio Alger stories and the like. Certainly, SC’s reign, if it ever existed, was very short-lived.

Regardless, your vision and understanding of capitalism are very romantic. Mine, which I expect to share later this week, are not. As a preview, I come to the question of “what is capitalism” from the point of view of a (former) true believer in the promises of liberalism, i.e., human rights, equal dignity, the absence of coercive power, the unfettered ability to improve one’s self, etc. Although I have achieved success as a capitalist, I cannot but conclude that capitalism is the antithesis of the liberal creed (and that the liberal creed is, in fact, a fig leaf to hide the true nature of capitalism).

–Scot

Here is the U.S. dividend payout ratio. It has risen significantly since the 1980s, and at times it even exceeds 1!

The ratio exceeds one because many corporations aren’t profitable. Ironically, the only companies I know who pay dividends even when they lose money are the big oil companies like Exxon Mobil.

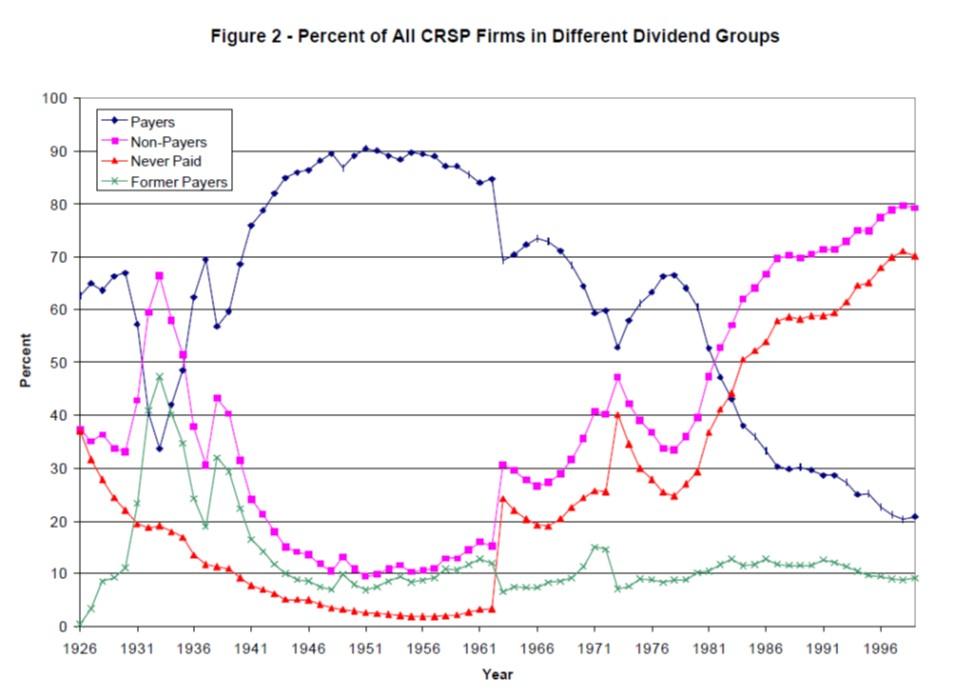

A paper of interest is Fama, Eugene F. and French, Kenneth R., Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower Propensity to Pay? (June 2000). Available at SSRN or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.203092

Here’s the “money” chart from the paper:

Miller and Modigliani’s work, along with CAPM and the Rational Market Hypothesis, form the bedrock of Modern Finance that currently drives the inner logic of capitalism. Their two key papers were published in June 1958 and October 1961 (the dividend paper).

Justin Fox’s The Myth of the Rational Market is a very readable account of the rise of Modern Finance.

The inner hierarchies of the corporations themselves are only one aspect of hierarchical power, and not necessarily the most important one. In Section 3.3 of ‘Growing through Sabotage’ (2020), we classified corporations as micro hierarchies, nested in meso-hierarchies and further in meta-hierarchies. If we consider the full spectrum of social hierarchy, we might find that today’s capitalism is the most hierarchical society ever.

This is a good way of thinking about things, actually. Thanks.

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons. First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake. But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons. First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake. But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.Still, asking the question of what do you really own when you own a financial asset is of extreme interest, even beyond the question of ownership and control of a corporation. Understanding the legal underpinnings of capital ought to help better understand the logic of capitalism itself.

In the final analysis, capitalism is not governed by individual capitalists, even though it often seems that way. It is not the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Morgans, Soroses, Zuckerbers and Musks of the world that run the show. And it is not even the corporations that they own that stir capitalism. Instead, it is the inner logic of capital that subjugates them all.

The gravitational pull of the logic of capitalism seems to grow stronger the closer you get to dominant capital. I don’t know if that is a phenomenon anyone has explored with CasP. Clearly, everyone is subject to the Market and, therefore, subjugated by the inner logic capital to some extent. But there are plenty of low-grade capitalists (individuals and firms) for whom differential accumulation (as compared to other capitalists) is neither a goal nor a concern, for example.

But once you find yourself in the orbit of dominant capital, which every publicly-traded company necessarily is, hoo-boy. Private equity firms and certain private conglomerates like Khoch Industries are the inner logic of capitalism personified.

the imperative of differential power drives and creates taller and taller hierarchical structures headed by state-supported large corporations, their top executives and key owners.

Is this always the case? One of the reasons I believe Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have such large market caps is because they’ve managed to capitalize the future earnings of those outside of their corporate hierarchies. Amazon, for example, makes a good amount of money through tribute paid by firms that will never reach the scale required to go public who want to expand their reach using the Amazon platform. The platforms of each of these companies allow them to “enclose” other corporations without purchasing them or giving them a seat at the dominant capital table. They are fractally replicating the market itself.

I just picked up English translation of The End of the Megamachine, which is available on SCRIBD for “free” (if you have a subscription) and for sale by all the usual suspects.

I am also skimming Peter Temin’s The Roman Market Economy (available at the same outlets as above)

David is correct. Here is a link to his essay.

The American Legal Realist movement of the early 20th century recognized that what most of us think of as “property” is actually a bundle of rights (e.g., the right to enjoy, the right to exclude, the right to alienate, the right to control, etc.) Interestingly, not all things that are legally considered property convey every one of the bundle of rights.

For example, the law considers patents to be property, but a patent only gives its owner the right to exclude others from making, using or selling the patented invention. The owner has no right to make the invention himself, if somebody else owns a patent patent covering a sub-system or component of the patented invention.

A share of common stock gives its owner no property rights in the underlying corporation whatsoever. It provides certain contractual rights (a different bundle of rights than provided by property), including the right to receive pro rata distributions of dividends, the right to pro rata distribution of residual value upon dissolution, and the right to vote in the annual shareholder meeting (and any special meetings that might be called), but that’s pretty much it.

Yes, a large enough block of shareholders can exert a great deal of influence on a management team, but that typically results in a negotiation between that block of shareholders and the management team, and activist shareholders are relatively rare (and tracked under SEC rules; the management team knows well ahead of time if they have activist shareholders).

Most companies no longer pay dividends. This has been the case since 1960s, after Miller and Modigliani successfully argued that the overall value of the company is not affected by the payment of dividends (see, Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares, 1961). Indeed, paying a dividend typically reduces the share price by the amount of the dividend (at least temporarily). Four of the ten U.S. largest companies (by market cap), including Amazon, Google (Alphabet), Facebook (Meta Platforms) and Tesla have never paid a dividend, and they are all sitting on piles of cash.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: Added link to referenced article

-

AuthorReplies