Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

November 10, 2022 at 6:45 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248574

With this being said, I think we need to distinguish ‘actual capitalization’ from ‘as-if capitalization’. As Ulf Martin explains, capitalization is an ‘operational symbol’ – namely, a symbol that does not simply represent the reality, but explicitly defines and creates it in the first place. And, to me, this feature suggests that for something to be labeled capitalization, it needs to be consciously articulated as such. In this context, we can think of ‘actual capitalization’ as one that the capitalizer explicitly spells out; as-if capitalization as one that the outside observer-theorist imposes; and in-between cases as weighed by their proximity to either pole. A wage payment in this scheme is actual capitalization if the capitalists and workers involved calculate it as such, but it is only as-if capitalization if the idea is merely imposed by the outside observer-theorist. And in my opinion, the same goes for discoveries of ‘ancient capitalization’: unless we can demonstrate that the price was consciously or at least explicitly articulated by the price setter as the discounting of expected further earnings, it remains a retrospective, as-if imposition. *** Martin, Ulf. 2019. The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery. Review of Capital as Power 1 (4, May): 1-30.

What you describe as “as-if capitalization” is a type of presentism, a fallacy that is often unwittingly embraced by those dealing with history, and I agree we need to be careful to avoid that.

As I allude to in my last two replies, I do not believe that discounting and capitalization are one and the same, and part of what I am trying to explore here is, if discounting is not necessarily capitalization, what distinguishes capitalization from merely discounting?

I am not quite ready to agree that consciousness of or explicit reference to discounting in the process of price-setting is enough for there to be capitalization, which means I don’t necessarily agree that the discounting of medieval bills of exchange was capitalization. The example used by Faulhauber and Baumol just applied a pro rata allocation of the bill’s mark-up (r/1+r) to determine what interest had already accrued and was due to the holder at the time he sold the bill of exchange. The buyer and seller were just allocating the principal and already accrued mark-up of the bill to the seller and the remainder of the mark-up to the buyer (who would have recourse for the entire amount of the bill if the debtor failed to pay).

I do think the existence and use of medieval bills of exchange caused merchants to become conscious of compounding and discounting and incorporate it into how they priced wages and goods, but that process may have already been underway in agrarian England as reflected by the enclosure of the commons to increase yields (I have found some scholars who seem to argue that the discussion of “yields” really refers to the rate of financial return to the landowner, not necessarily to increased rate of production of the commodity on enclosed land).

To me, sabotage starts with the managed scarcity of money, which is the basis for the differential accumulation of property.

Could you clarify what you mean by this? While I think that the MMT/Chartalist crowd have gotten a lot wrong, I do think there is some validity to the idea that the State controls the creation of currency, and forces society to utilize their currency by requiring that taxes be paid using their currency. The legal structures of taxation then permit tax avoidance for the wealthy, and this facilitates differential accumulation. But money and currency are not the same thing, so I’m unsure if this is what you are referring to.

Sure. Let me try it this way (my overarching theory is still coalescing).

I am referring to money broadly, which I believe even under MMT includes both currency and bank deposits.

Regardless of what constitutes money or how we theorize it, money is not neutral. If property is theft, money is assault and battery.

Although it encloses nothing, money is a gate that stands between us and our survival. To access the necessities of life, one must have money, and it is the relative need of money that creates power differentials among individuals, defining and narrowing the options of those who do not have it while creating and broadening the options of those who do. While capital is the stock of capitalist power, money and debt are its flows.

It is the relationship between debt and money that ensures the scarcity of money and the flow of power to capital. There is always more debt than there is money to pay it. This is especially true in a credit money system such as the one we have, where banks create money on the precondition of a promise to pay the bank the money created plus interest in the future (normally, we call this “lending at interest,” but there is no loan, just credit extended on the promise to pay that was fraudulently premised on the fiction that the bank is giving the person money that the bank already possesses).

Yes, MMT shows us we can model the current credit money system as if it is the state that creates money by spending it and destroys money by taxing it away, but empirically that is not yet true, and significant changes are required to transform the theory (MMT) into reality (MMR). Banks create more than 90% of all money in the first instance, and the reserves follow weeks or months later.

If we ever move towards changing our monetary institutions to make MMT “MMR,” I am concerned that it will largely be illusory, a move to further entrench the power of dominant capital, which MMT leaves largely intact. MMT would only affect the rate of differential accumulation, not differential accumulation itself.

I do not object to credit money per se, I just think credit money should not be interest-bearing except in cases where the proceeds are used for purely financial purposes (e.g., speculation or stock buybacks) or other uses unrelated to the production or consumption of commodities. If MMT were to embrace the idea that the state lends the money into existence instead of spends it into existence, then the private servicing of debt would perform the same function as paying income taxes, which could be eliminated for most people. Why does MMT choose to keep the banks in the middle? (NOTE: MMT says that repaying debts destroys money, but that really just means the “money” associated with principal payments is removed from a deposit account on the liability side of the bank’s books. It does not mean that the principal payments don’t show up elsewhere as an asset on the bank’s books, replacing the “loan” it “repaid.” While principal payments are credited against the loan to reduce the book value of the loan, as a legal and accounting fiction, the principal is being “returned” to the bank and cannot and does not disappear. I can find no legal or accounting basis for concluding banks do not treat principal payments as a return of capital, which is not income to them for tax purposes, and nobody who asserts otherwise has proven me wrong when I’ve asked them to do so.)

Credit money was an important innovation and is the foundation of capitalism and capitalist power. To me, all MMT does is recognize that credit money supply is not materially constrained the way hard money supply is, which means we do not have to ensure that the masses remain poor so a few can get rich. In a credit money system, money is not a store of value, capital is, and hoarding capital does not withdraw money from the system. This means policies like austerity are unnecessary artifacts of a bygone age that can be abandoned.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin.

This is a great question Scott, and I think that a lot of good answers will be found in the work of Elinor Ostrom

First, in all of recorded history, has humanity ever enjoyed a world free from sabotage?

It would seem to me that sabotage, as used by Veblen, and Di Muzio, and CasP more generally, would require property that is legally defined in order to exclude access. With legal exclusion, we have the development of the various tools that are utilized in both senses of sabotage. Thus if we want to look at a world without sabotage, we must necessarily look outside the world of enclosures, and this would then mean looking at the world of Commons Pool Resources. Ostrom’s work in this area is very extensive, and has covered everything from physical resources, to intellectual resources.

Second, relatedly, what does a world without sabotage look like? Do we have examples or just a utopic vision that is yet to be imagined or articulated?

I don’t necessarily think that we should limit ourselves to the work of Elinor Ostrom, but it is a good starting point. I certainly don’t hold Ostrom as sacrosanct, and it has been a few years since I read her works, but I feel like her research is invaluable for informing this particular subject. Some Ostrom Recommendations 1. Rules, Games, and Common Pool Resources 2. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons 3. Working Together: Collective Action, The Commons, And Multiple Methods in Practice 4. The Future of the Commons Beyond Market Failure and Government Regulation

Pieter,

Thank you for the recommendations. I will take a look.

I agree with the centrality of property rights to sabotage, but what about money itself? To me, sabotage starts with the managed scarcity of money, which is the basis for the differential accumulation of property.

November 7, 2022 at 9:51 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248555If capitalization is the only pricing mechanism in capitalism, this would imply that what Marx calls exchange value is, in fact, just discounted use value, i.e., exchange value is capitalized use value.

Why do you say that discounting capitalizes use value (rather than power)?

Jonathan,

I’ve taken the time to distill down the observation that inspired my original comment from the unnecessary confusion of use value/exchange value, Sumer, etc.

Basically, my question was “are commodities, including labor, priced the same way as capital assets”? Originally, I thought of mark-up as entailing the arbitrary addition of desired profits to costs, but based on equations 3-6 below, it seems we can model wages paid to labor as the present value of future profits accruing to the benefit of capitalists, discounted for risk. This “discovery” is so obvious in hindsight that it probably isn’t new to anyone else here.

The reason I bothered referring to Marx at all is because of the concepts of use value, exchange value, and surplus don’t seem to account for time and risk. When viewed through the lens of compounding/discounting, value is either in the past/present, or it is in the future, and there is no surplus, only discounting or compounding based on the perception of risk. “Mark-up” is really the the allocation of rewards based on who takes the risks (at least that is what a capitalist might argue), and there is really no value outside of that.

I don’t think this view of how prices are set affects CasP theory negatively because, after all, setting the discount rate is a pretty straightforward assertion of power, as is rendering people unable to object to the allocation of rewards (e.g., through structural violence that requires labor to accept the wages offered or cease to exist).

I will leave it to you to determine whether this instance of discounting is an example of capitalization, but I provide some thoughts below. Now to the analysis.

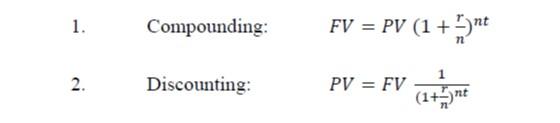

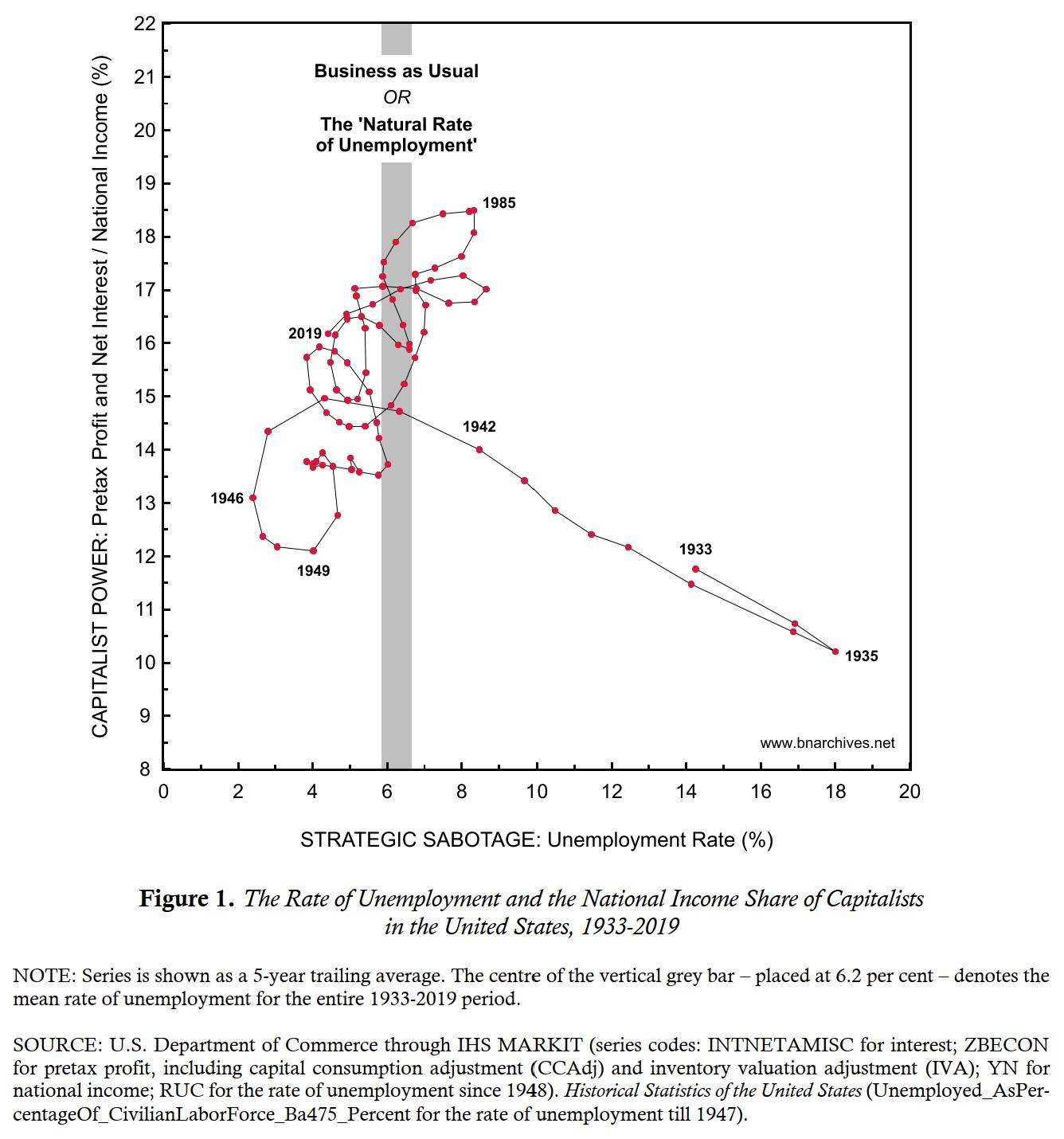

Beginning with the basic formulas for compounding and discounting, where FV is future value and PV is present value:

Assuming n=1, t=1, wages paid to labor today (Wagest) are the only input costs associated with revenues generated by the future sale of commodities produced by said labor (Revenuest+1), and the capitalist expects a rate of return r from the future sale of said commodities, we can express Revenuest+1 as the expected FV of Wagest (PV) using the simplified compounding formula:

Equation 6 is the same form as the capitalization formula (5) found at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Thus, wages paid to labor today can be viewed properly as the “risk-adjusted discounted value of expected future earnings” (i.e., Profitst+1), i.e., wages can be viewed as the capitalization of expected profits (or power, if you would prefer). As you’ve said, “capitalization represents the present value of a future stream of earnings: it tells us how much a capitalist would be prepared to pay now to receive a flow of money later.” Capital as Power, at p. 153.

Of course, unlike stocks and bonds, there is no distinct property right associated with the payment of wages, i.e., when a capitalist pays wages, he is not acquiring a capital asset that is distinct from his business. However, the capitalist already owns the business that owns the products produced by the labor paid for by the wages, and, therefore, the capitalist is entitled to the income stream arising from the sale of said products. The capitalist pays wages to secure a future income stream, and the capitalist sets wages by discounting that future income to a present value adjusted for risk.

November 6, 2022 at 9:58 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248550Bagnall’s text is intended for the specialist, and I find it really hard to follow. I do understand, though, that: 1. The discussion involves fragmented ancient evidence that the experts piece together, fill the in-between blanks and then interpret the results as if they were modern financial transactions. 2. The transactions involved aren’t purely monetary, but hybrids of money and ‘in-kind’ flows. This mix means that even when the transactions are clearly stated — and most aren’t — their underlying magnitudes are only partly specified:

We can now summarize the types of transactions involved in the Tetoueis documents and the new Berlin text: (1) loans in kind to be repaid in kind with interest of 50 per cent ;20 (2) loans in money to be repaid in kind, with both amounts specified but not the interest; (3) loans in money, amount specified, to be repaid in kind at a price not specified but reduced by a third; (4) loans in money, with amount not specified, to be repaid with a fixed amount of produce. (Bagnall: 93)

With this in mind, interpreting the ‘pricing’ of these contracts as if they were acts of capitalization, however embryonic, seems to me far fetched.Thank you for reviewing and responding.

As I see it, medieval bills of exchange were just supply on demand contracts in reverse. Both types of agreements involved disguised interest-bearing loans made in connection with the sale of goods in which the delivery of the money and the goods differ in time. For medieval bills of exchange, the goods are delivered today in exchange for payment at a later time subject to interest. For the sale on delivery contract, the money is delivered first, and the sale price of the goods delivered at a later time is discounted by a discount rate (at least that is what Bagnall argues). As a result, the face value of a sale on delivery contract is the present value of a future transaction discounted for risk (the discount rate). If Bagnall is correct, discounting was known at least as early as the 4th century CE, and others argue that it was known much earlier.

NOTE: Faulhauber and Baumol, upon whom you rely at page 155 of Capital as Power (2009), seem to misunderstand the nature of medieval bills of exchange. It is not true that “Italian merchants allowed customers to pre-pay their bills at a ‘discount’, applying the rate of interest to the time left until payment was due.” The amount of the bill of exchange remained fixed, due and payable by the customer. The discounting occurred between the merchant and the exchange bankers, allowing the merchant to receive payment and the exchange bankers to enjoy the mark-up as payment and trade bills amongst themselves in settlement of debts. See Colin Drumm’s discussion on his substack.

Whether discounting is always capitalization is a separate question. The “after market” of bills of exchange may be a valid basis for viewing only the discounting of bills of exchange as capitalization and not supply on delivery contracts, given the apparent absence of such an after market for supply on demand contracts. Still, supply on demand contracts used the discounting formula directly in the pricing of the exchange and, more likely than not, the buyer realized income by selling the goods he purchased for more than the discounted price for which he purchased them. Value is value because money makes it so.

October 30, 2022 at 5:49 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248492Thank you Scot. I read Chapter 2 in Tan’s book, ‘The Use and Abuse of Tax Farming’, and found it really interesting. What I didn’t find, though, is any evidence that tax farmers discounted future earnings — in Rome and elsewhere. In your post, you write that

Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on.

Well, from Ch. 2 in Tan’s book it seems that historians of tax farming know relatively little, if anything, about the profitability of tax farmers. One guesstimate puts the rate of profit of Roman publicani in a certain region between 8-215%, while another speculates it was 30% (pp. 57-8). But no one really knows. Similarly, judging by this chapter, nobody knows what calculations contract bidding was based on. The chapter does not mention discounting/capitalization of future earnings, let alone offers any evidence that such discounting/capitalization took place. Reading between Tan’s lines, my impression (again, nobody really knows) is that contract bidding was largely a matter of arms wrestling. When the tax farmers overcame their mutual disdain and acted in unison, prices were low and they could make a bundle; when they bickered, prices were high and they earned little or even lost (and sometimes demanded retroactive rebates, no less). There was no need for any risk coefficients and raising the normal rate of return to the power of five. It was simply a matter of strongmen groping for what the ‘Republic will bear’. This isn’t an area I know enough about, and there may be other studies where discounting of tax farming is discussed and assessed. But without such evidence, the claim that these contracts reflected discounting seems to me unsubstantiated.

Jonathan,

Here is a link to a 1977 article by Roger Bagnall entitled “Prices in ‘Sales on Delivery'” from the journal of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies.

The transaction Bagnall describes at pages 91-92, which occurred in the 4th century CE, is similar to a medieval bill of exchange, i.e., a disguised loan at interest, but the money is delivered before the goods. The interest (or discount) rate (r) is 50%, resulting in a discounting of the price of the goods at the time of delivery by 33%. Implicitly, according to Bagnall, the 4th century lender appears to have calculated the discount (d) of 33% using the discounting formula, or its equivalent, that Faulhauber and Baumol claim Italian merchants invented in the 14th century CE, i.e., d = r/(1+r); when r = 50%, d = 33%.

At page 287 of his 2013 book The Roman Market Economy, Peter Temin cites to the Bagnall article to argue that such contracts were used in Rome in the 3rd century BCE.

Please review and let me know what you think. Thanks.

Here is an interesting question about capital as power from Guy Tal (Twitter thread: https://twitter.com/guytal10/status/1582666152064344064)

Isn’t there a danger of transforming this argument [capital as power] into a mirror of the util theory? If capitalists only care about the effect a certain asset has on capitalization, and since capitalization is differential power… Couldn’t we say that this power is virtually the ability to sabotage society’s welfare through prohibiting this asset’s use? And that wouldn’t be just the mirror of the asset’s possibly contribution to society? Then in order to specify the material foundation of this power (the ability to wreck sabotage and affect society mediated by ownership over ideas and materials) we eventually restore similar problems of mainstream economics?

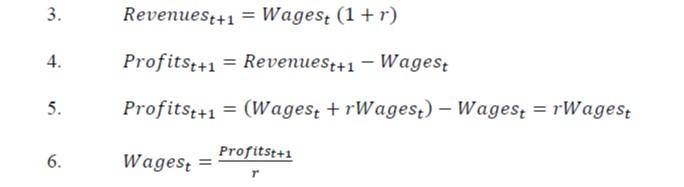

In CasP: 1. capitalization = (future earnings x hype) / (risk / normal rate of return) And: 2. differential capitalization = (differential future earnings x differential hype) / differential risk My understanding of Guy’s argument is that, if the elements on the right-hand side of Equation 2 are determined by various forms of sabotage, then the overall effect of this sabotage, reflected in differential capitalization, is in fact an inverse proxy for the forgone utility to society of the sabotaged entities/processes/institutions. The greater/lesser the utility of the sabotaged item, the greater/lesser the differential capitalization of the saboteurs. Is this argument valid? I’d say that the answer is a tiny yes and a very big no. THE TINY YES. In the aggregate, for sabotage to generate capitalist earnings and hype and to reduce risk it must be applied to something that is ‘useful’ to society (I prefer to expunge the neoclassical term ‘utility’, whose meaning and quantity are forever unknowable). Thus, sabotaging or threatening to sabotage the overall level of oil production, the general application of food-growing technology, cultural creativity, or freedom of movement is likely to affect the overall level of capitalist income, hype and risk. But this loose association does not imply that capitalization in general and differential capitalization in particular are inverse proxies for society’s wellbeing. The key reasons are as follows. THE BIG NO (1): The connection between sabotage and capitalization is nonlinear: too much or too little sabotage are likely to undermine capitalization. This nonlinearity is why, following Veblen, we speak not of sabotage but of ‘strategic sabotage’. In the U.S. chart below, for example, we see that unemployment, a general form of sabotage, relates to the capitalist share of national income, but that the relationship is nonlinear (https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/663/). And this nonlinearity means that the same capitalist share of national income (for example, 13%) can be related with more than one level of sabotage (in this case, with unemployment rates of 2.5% and 10%). In other words, knowing the capitalist share of national income tells us little or nothing about the lost wellbeing of forgone employment.

THE BIG NO (2): A given level of sabotage need not translate to a unique level of earnings/hype/risk, let alone to unique differential magnitudes for these variables. For example, in our work we found that Middle-East Energy Conflicts tend to boost the differential rates of return of the Petro Core (leading oil companies) – but as this chart shows, the magnitude of this effect varies greatly across conflicts. So here, too, knowing the differential consequences of sabotage tells us very little about the wellbeing they presumably sabotage.

THE BIG NO (2): A given level of sabotage need not translate to a unique level of earnings/hype/risk, let alone to unique differential magnitudes for these variables. For example, in our work we found that Middle-East Energy Conflicts tend to boost the differential rates of return of the Petro Core (leading oil companies) – but as this chart shows, the magnitude of this effect varies greatly across conflicts. So here, too, knowing the differential consequences of sabotage tells us very little about the wellbeing they presumably sabotage. THE BIG NO (3): In the capitalist mode of power, ‘wellbeing’ is not some externally given entity, but a constructed imposition that conditions people to accept specific notions of necessity and desirability (think: junk food, debilitating entertainment, urban sprawl, private transportation, overmedication, advertisement, patriotism, private=good/public=bad, etc.). In our view, this imposition of ‘preferences’ is a major form of sabotage. And, if we are right in this claim, then when capitalists threaten to withdraw access to these imposed preferences, they are not limiting wellbeing, but augmenting their own sabotage… So, I’d say that, all in all, the capitalized consequences of sabotage cannot be considered the inverse of social wellbeing, let alone of neoclassical utility.

Utility theory and utilitarianism are two different things. Since Guy refers to “util theory” and Jonathan seems to respond in kind, I assume we are talking about utility theory.

I don’t see any similarity, correlation, congruence or potential convergence between utility theory and CasP theory, especially as it relates to mainstream economics.

First, both utility theory (as employed in mainstream economics) and utilitarianism are normative theories, and CasP is descriptive, not normative. CasP only seeks to describe capitalist behavior, not to shape it. If anything, CasP portrays capitalist behavior as insane, not rational.

Second, utility theory asserts that rational actors make decisions in order to maximize utility, and CasP rejects the notion that utility (as utils) is an objectively measurable quantity. As much as I don’t think “hype” exists as CasP theory expresses it (as a scaling factor), my objection can be overcome relatively easily by re-expressing hype as something akin to entropy (a separate quantity that is solved for independently to account for error between expected future profits and actual future profits). In any event, utility theory claims to measure absolute quantities, and CasP claims what actually matters is differences between quantities, not the quantities themselves.

Finally, focusing on Guy’s question itself, we need to reintroduce utilitarianism, which is the normative theory of mainstream economics (neoclassical economics is applied utilitarianism, political rhetoric, and not a science at all). In the tradition of Bentham and Mill, mainstream economists assume free market capitalism is morally right because it produces the most good, i.e., it maximizes the “overall good” of society as a whole, not just the good of capitalists at the expense of everybody else. Merely by describing capitalist action as sabotage, CasP categorically rejects this foundational assumption of neoclassical economics. Mainstream economists employ utility theory normatively to reinforce and prove the idea that capitalism promotes the common good, and I do not see how anyone can adapt CasP theory to make the same argument.

Guy’s question is insightful, though, because one could argue that neoclassical economics was the capitalist response to, and inspired by, Marx’s criticism of capitalism using classical economics (Henry George argued that neoclassical economics was a response to him, not Marx). Can capitalists create “mainstream econ 3.0” by doing to CasP what mainstream econ 2.0 did to Marx (and George)? No, because societal sabotage is irreconcilable with maximizing the overall good of society as a whole. An arsonist who starts a fire can never be considered the hero, even if he puts out the fire he started, and capitalists must be the heroes of mainstream econ, whatever version it may be.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: removed extraneous text that was inadvertently included

October 12, 2022 at 10:12 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248443I am not sure if I am adding anything to this discussion. However, I think we should be clear on definitions. The first steps in any academic argument must be to agree on (a) a priori assumptions and (b) definitions of terms. Leaving aside a priori assumptions for the moment (for we can’t even expose and examine a priori assumptions without agreed terms) [1], what are our definitions of capitalism, capital and capitalization? 1. Capitalism Is the Wikipedia definition for Capitalism serviceable here? “Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private property, property rights recognition, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. In a market economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to manoeuvre capital or production ability in capital and financial markets—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.” When we look at the Wikipedia definition in Wikipedia, we note that a whole list of terms in this definition have color-highlighted. underlined links. These further definitions are essential ingredients to understanding the “capitalism” definition. I’ve sometimes been faced by arguments that capitalism is non-existent, as a system, because it is not pure and not ubiquitous. The biggest plum pulled out of this magic pudding is the mixed economy argument. This argument is much like saying policing does not exist because it is not pure and not ubiquitous. It is now commonly asserted that capitalism is a global system. I concur. This is despite the fact that it is not pure and not ubiquitous. Purity and ubiquity are not possible for any finite system in the cosmos or in the world. Any system is always embedded in something that is “all systems together” (the monistic totality) and we can always note combinations, conglomerates, agglomerates. The best analogy (and it is not just an analogy but a monistic homomorphic congruence) is a net. Capitalism extends its net, of connections, and (dynamically) nets the world. It hasn’t netted the whole world. Small stuff gets through. Big stuff breaks through, tears the net. But ever the net is expanded, repaired, meshed out autocatalytically, to use Ulf Martin’s applied term. Ultimately, large fundamental forces can (and will) “explode” the net or rapidly unravel the net but that is another topic. Looking back in time (which is more the issue here), we can nominate capitalism’s starting point, with an agreed comprehensive definition of capitalism. 2. Capital Next we get to the definition of “capital”. Here, “CasP (Capital as Power) already has a problem with classical economics encompassing capitalist economics and Marxist economics. Note 1 – And our agreed terms can already contain unexamined a priori assumptions. How do we deal with that? I would argue that we can only do that iteratively, after provisionally agreeing on terms, by then examining the set of currently agreed terms, currently agreed principles and currently agreed methods. Thence we find anomalies (internal inconsistencies) and lacunae and then resolve them if possible. We keep trying to iron out and mend our investigative system out until we agree we can find no more wrinkles and no more holes, for the present at least. Then we apply it to the real world for the necessary empirical testing.

Thanks, Rowan.

The point of contention here is not the definition of capital, capitalism, or even capitalization, it is the origins and terminus a quo of capitalization (its earliest start date). Jonathan and I agree that capitalization was established “as the heart of the capitalist nomos” some time in the second half of the 20th century (Bichler and Nitzan say by the 1950s, but I place it in the 1960s after the publication of Miller’s and Modigliani’s “Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares ” in 1961). See p. 158 of Capital as Power (2009).

Bichler and Nitzan find the origins and terminus a quo of capitalization in fourteenth century Italy:

Simple computations in this spirit were used as early as the fourteenth century. Italian merchants allowed customers to pre-pay their bills at a ‘discount’, applying the rate of interest to the time left until payment was due. Initially, the practice was relatively limited.

Capital as Power (2009) at p. 155 (citing Faulhaber’s and Baumol’s “Economists as Innovators: Practical Products of Theoretical Research” at pages 583-584

By “bill,” Bichler and Nitzan are referring to a bill of exchange, not what we think of as a bill today, which is just an invoice from the seller to the buyer. A bill of exchange is a financial instrument (contract) that simulates a short term loan at interest by having a price equal to the principal plus all interest due at the end of the term. By “merchant,” Jonathan is referring to the holder of the bill of exchange, which by the end of the term may or not be the merchant who sold the merchandise in exchange for the bill of exchange (which was presented by the buyer’s agent to the merchant, not by the merchant to the buyer).

If the merchant had actually made a loan at interest, early payment of the loan would automatically exclude any interest that had not accrued because it was not due, i.e., “discounting” is automatic for the early payment of a loan, but not for a bill of exchange. Merchants who had accepted the buyer’s bill (i.e., his unsecured promise to pay) and agreed to discount a bill were merely honoring the underlying intent of the contract by foregoing interest that would not have been due but for the form of the loan.

For whatever reason, Bichler and Nitzan privilege this form of discounting as being in the “spirit” of his capitalization formula, presented at pages 153-155 of Capital as Power (2009), while seemingly ignoring others. But you don’t actually need their (or any) version of the capitalization (discounting) formula to provide this type of discount, all you have to do is calculate the interest due at the time of early payment, subtract it and the principal amount from the par value of the bill, and that is your discount. Ta daaa.

In some ways, I am both more and less demanding of what the earliest example of capitalization could be. I don’t think it should be limited to simulating the early payment of an unsecured loan, as Bichler’s and Nitzan’s example is, because that does not capture anything that looks like buying and selling shares on a stock exchange, upon which CasP theorists focus with rare exception. The key is at risk future income, regardless of how that future income is expressed (e.g., whether as profits or interest).

The earliest and closest analog to contracts to purchase future income (as opposed to just making an loan or simulation of one) of which I am currently aware is tax farm contracts in which a private party purchased the right to collect tithes/taxes from defined territories of the state (i.e., the farm), typically for a set term of years (e.g., 5 years). Hammurabi employed tax farmers. So did the Ptolemies of Egypt and the aristocrats of the Roman Republic.

In Rome, tax farm contracts were put up for auction (you know, sold on a market), and applicants bid on the contracts. The winning bid got the contract, and the Roman Republic received money equal to the winning bid as full payment for any taxes the bidder might recover. Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on. Interestingly, the buyers of tax farm contracts were often the Roman equivalent of a corporation with shareholders. But, hey, Sumer. Nothing to see here.

I am currently reading James Tan’s 2017 book about Roman tax farming (among other things), entitled Power and Public Finance at Rome, 264-49 BCE. The book focuses on how Roman aristocrats of the Republic era relied on tax farming to keep the state weak while enriching themselves and keeping their aristocratic rivals at bay. The decentralized aspects of Rome’s mode of power (the Roman republic served its aristocrats, not the other way around) disappeared when Julius Caesar seized power and effectively became the state.

As interesting as I find all this, it is tangential to my original post in which I queried whether wages are priced in a manner that capitalizes labor’s contribution to the at-risk income. I feel confident that is the case today because the typical response to seeing 15% of profits evaporate in the present and the future is to layoff 15% of the wages (they don’t really think in terms of other human beings).

If you want, I would be happy to share copies of the journal papers I cite above. Just let me know.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: added formatting to quote

October 12, 2022 at 1:48 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248440Of course, we can never know for sure, but it seems to me that the ontology of the Sumerians, whose gods created humans to be their slaves, whose Anu was supreme authority and Enlil turbulence at will, whose ironclad rate of interest was religiously sanctified, and whose military conflicts were won and lost by competing gods, was very different.

So what you are saying is that Sumer had a “risk free” rate of return (i.e., the financial benchmark of an ironclad rate of interest that was religiously sanctified) for loans collateralized by land and the person of the debtor (and the persons of his kin, most likely).

Kidding aside, I really don’t know why you have fixated on Sumer (you brought it up, not me) to dismiss the possibility that capitalization (discounting) predates capitalism by potentially thousands of years. I was thinking specifically of Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic when I suggested the possibility, but hey, Sumer.

October 11, 2022 at 11:32 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #2484331The future was deemed unknowable, subject to the whims of the gods.

At best, we have evidence of what elite Sumerians said in writing, but we don’t know what they actually thought or believed.

Today, neoclassical economic dogma essentially claims that the market is an all-seeing, all-knowing god that decides who wins and who loses. economically. Our future is unknowable because it is subject to the whims of the market.

But we know better because we can see how capitalists own and control the market, a fact that may not be so obvious far into the future, long after the age of capitalism has ended. Indeed, if humanity survives for another two thousand years, it is likely to view the theodicy of our capitalist era much as you view the theodicies of ancient civilizations such as Sumer.

October 11, 2022 at 9:48 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248432I came across a very interesting passage recently in a paper on virology. (I am not a virologist but I read papers in it from time to time.) It referred to self-assembly and coded assembly. The natural world exhibits features of both self-assembly and coded assembly at the level of life. Let us assume here that life begins at viruses. At the non-life and/or inorganic level, the natural world exhibits only self-assembly (where it is not exhibiting the plain old general cosmic process to ever greater entropy). A good example of self-assembly is the formation of a crystal under natural conditions. The paper I refer to states: “In the same way that a roll of magnets will spontaneously assemble together, capsid proteins also exhibit self-assembly. The first to show this were H. Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams in 1955. They separated the RNA genome from the protein subunits of tobacco mosaic virus, and when they put them back together in a test tube, infectious virions formed automatically. This indicated that no additional information is necessary to assemble a virus: the physical components will assemble spontaneously, primarily held together by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150055/ People on this forum may well assume at this point I am down an esoteric rabbit hole unrelated to political economy. I don’t entirely think so but it’s a long discussion and I’ve never succeeded in making my case. Suffice it to say, the task in political economy is in my view to stop looking for natural laws in political economy (aside from the natural laws involving the exothermic, endothermic and self-assembly reactions which we utilise in the real economy for inorganic production and the biological laws of (RNA and DNA) coded assembly we utilise in organic production like food and fibre production). At all levels above this, political economy is about complex human behaviours and encoded laws (i.e. legal laws, regulations, conventions, rituals etc.). This is my view which is obviously partially derived from CasP insights.

Rowan,

I made an off-hand reference to it earlier, but I am considering the possibility that hierarchies in human societies are self-assembling through the transmission of debt-based obligations, which include but are not limited to strictly monetary debts. Debt-based obligations are themselves a form of code that establish the senior party (e.g., the creditor or manager), the junior party (e.g., the debtor or subordinate), and the subject/object of their differential power (e.g., a loan of money at interest or a job). Capitalism is constructed of many level os debt-obligations, but so were prior modes of power.

One of the reasons I am looking well past the earliest date CasP assigns to the start of the capitalism (which I view as a few centuries too early) is to understand whether and how debt obligations worked differently in other modes of power. Again, I view western European feudalism as an aberration because it shunned finance as a state institution, whereas earlier modes of power were built around institutions that provided what were equivalent to (or at least analogous to) “financial” functions even in the absence of what we tend to view as money (e.g., coins and modern money).

October 11, 2022 at 8:36 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248431With this in mind, should we trace the origins of capitalization back to Sumer? In my view, the answer is no:

- One of the distinguishing features of the capitalist mode of power is that power appears as a universal quantitative relationship between entities (relative prices). This feature first emerged in the early the European Bourgs and was later formalized by Johannes Kepler to describe the forces of the cosmos. In Sumer, powers (in plural) were stand-alone qualities. The idea that power was a universal quantitative relationship between entities was inconceivable.

- The “larger use of credit”, as Veblen called it, also a key feature of the capitalist mode of power, presupposes the growing universality of the price system. This condition did not exist in Sumer.

- Forward-looking capitalization is a derivative of the larger use of credit, again, inconceivable in Sumer

- Differential capitalization emerges from the wider use of capitalization, unimaginable in Sumer.

Of course, if you can show that these observations are false, or that tracing capitalization back to Sumer is indeed useful and revealing, I’ll withdraw these contestations.

If evolutionary scientists can look to other primates for the origins of the human species, we can look to Sumer for the origins of capitalization (discounting future value to present values), and it is even more obvious why we can do so. Can we look to Sumer for origins of the capitalist mode of power in every detail? No. Sumer was missing a lot of essential ingredients for that. But can we look to Sumer for the origins of capitalization? Sure.

Anything that affects future earnings, hype, risk and the normal rate of return impacts capitalization. But undermining these factors must be intertwined, or at least go hand in hand, with autonomous, non-capitalized form of organization to address the material needs and wellbeing of most people. Without these alternatives, the power logic of capitalization remains intact and its quantities will rebound.

Again, I highly recommend Bob Meister’s Justice Is an Option, which posits the idea of using financial tools to “capitalize” the disruption caused by social movements; i.e., decapitalization through capitalization.

From the book description:

More than ten years after the worst crisis since the Great Depression, the financial sector is thriving. But something is deeply wrong. Taxpayers bore the burden of bailing out “too big to fail” banks, but got nothing in return. Inequality has soared, and a populist backlash against elites has shaken the foundations of our political order. Meanwhile, financial capitalism seems more entrenched than ever. What is the left to do?

Justice Is an Option uses those problems—and the framework of finance that created them—to reimagine historical justice. Robert Meister returns to the spirit of Marx to diagnose our current age of finance. Instead of closing our eyes to the political and economic realities of our era, we need to grapple with them head-on. Meister does just that, asking whether the very tools of finance that have created our vastly unequal world could instead be made to serve justice and equality. Meister here formulates nothing less than a democratic financial theory for the twenty-first century—one that is equally conversant in political philosophy, Marxism, and contemporary politics. Justice Is an Option is a radical, invigorating first page of a new—and sorely needed—leftist playbook.

Re-upping a link to a recent panel discussion with Meister regarding the book (in which he cites to Bichler and Nitzan) and his ideas.

October 10, 2022 at 10:42 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248417Scot Griffin, I would counsel throwing classical economics’ value theory and Marx’s value theory out the window. Just throw it all out the window and start thinking from scratch again. This equates to throwing Utils and SNALTs out the window.

Thanks, Rowan.

Actually, I think what I’ve done here is to throw everything out the window, including CasP’s asserted history of modes of power (including the history of capitalism itself). Again, if there is only one pricing mechanism in capitalism, i.e., prices as the risk adjusted discounting of future value to present value, then there is no such thing as exchange value, use value, or surplus, and one needs to look elsewhere to site exploitation of the ruled (I look to money itself, regardless of how instituted).

I presented my thoughts as questions not because I was baffled or confused, but because I was trying to provoke responses that go beyond rejecting the very idea that the basic concepts that animate capitalism have been with us for thousands of years, at least since ancient Athens and Rome, if not earlier (e.g., Sumer). What makes capitalism “capitalism” is modern money, i.e., credit money, and the reason why modern money came about is the Catholic church prevented the integration of finance with the monetary system of “feudal” Europe, something that had been a hallmark of both Athens and Rome (aka “the state of hard money”). Finance was always part of the state of money-based societies until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Catholic church’s effort to establish itself as its own sovereign power by preventing the formation of state financial institutions. Private bankers had their own ideas.

Feudalism was an aberration, not an evolution of prior modes of power, and CasP’s story of prior modes of power is heavily burdened by Marx and those who came before him urging a new theodicy to explain extreme inequality in view of a new mode of power that claimed to stand for equality. While the private credit/money system of Europe did first come into existence around the 14th century, capitalism could not and did not exist until that kind of financial system merged with the “state” England with the founding of the Bank of England in 1692, creating what we understand today as modern money. The fact that some of what happened in the preceding 200-300 years looks a lot like capitalism only emphasizes that many of the concepts of capitalism predate it by a long while.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: edited for readability

October 10, 2022 at 10:17 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #2484161. I don’t understand the idea that capital discounts use value. The processes of power may or may not involve the creation of use value, but, in my view, capitalization is entirely independent of it.

To a certain extent, I am arguing that there is no such thing as exchange value, use value, or surplus. If we consider wages to be priced the same way capital assets are priced, i.e., wages represent the capitalization of value added by labor, then there is only one value, and that is equal to wages paid.

2. In Sumer, wealth wasn’t thought of as Capital in the modern sense, let alone as discounted future earnings. Wealth was obtained by force, confiscation and royal/religious decree. There was no notion of “normal earnings” and “risk”. The future was deemed unknowable, subject to the whims of the gods. I don’t see the point of generalizing the modern ritual of orderly capitalization to pre-capitalist societies, let alone ancient ones.

Sumerians understood the concepts of both compounding interest and discounting (e.g., via tax farm contracts), which are the inverse of one another. The fact that we have no evidence that Sumerians were as sophisticated about risk-adjusted discounting as the moderns does not mean they did not understand the basic outlines of it well enough for us to consider Sumerian wages as the “capitalization” of labor just as wages are today (if you accept that frame).

Again, I’ve argued in other comments in the forum that wages are priced like commodities and not capital assets, that capitalism, in fact, has two very different approaches to pricing things, but there is a good argument that “capitalization” is the pricing mechanism for everything in capitalism, that the perceived “mark-up” of commodities is just the accumulation of the risk-adjusted discounting of future value that the capitalist captures as profits through exchange of the end product, which eliminates the risk. What we call profits are just unwinding the discounting of the input costs to the seller’s benefit. Capitalists compress the future into the prices they pay for inputs, and they decompress that future when it becomes the present at the time of sale. Monetary exchanges are a time machine.

While capital could not exist without modern money, which allows wealth to accumulate as capital without affecting the circulation of money, there is a lot of evidence that most, if not all, of the basic concepts of capitalism, including risk-adjusted discounting and limited liability corporations, have been known for thousands of years. The conflict between hoarding and circulating hard money just prevented capitalism from coming into existence. Rome and Athens were too smart to allow private bankers to compete with the state money/credit system and ensured finance was part of the “state of hard money.” The only reason we have capitalism is because the Catholic church created a situation in which private finance created its own international money/credit system that came to dominate the intentionally anemic monetary (only) systems of individual sovereigns.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: corrected a typo

-

AuthorReplies