Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Jonathan,

If neoclassicals and Marxists want to assign a portion of the value of an end product as arising from the capital goods that helped produce them, they can do so by dividing the depreciation for a period by the number of end products produced in that period to get the per unit contribution of the capital goods.

Regardless, capitalists depreciate the cost of their capital goods over time as an operating expense to smooth out their profits taxes. From an accounting perspective, there is no way around the fact that capitalists consume their capital goods, they do not accumulate them.

If economists want to theorize a different system in which capital goods are accumulated (which I don’t think they have to do, they can just admit that depreciation, amortization and depletion are ways to reflect the contribution of capital to an end product), that system is not capitalism. If they do choose to do the right thing and look to accounting tricks like depreciation to understand capital’s contribution to the cost of the end product, then the contribution of capital goods in all cases reduces down to monetary units, but I don’t know if that tells us anything about the value of capital’s contribution.

Personally, I think the reason why they insist on capital being a material thing is they want to avoid admitting that money and finance are central to capitalism. They want to continue in a world where physical commodities are bartered and no money exists, thus keeping the discussion in the cooperative world of industry and avoiding even acknowledging the predatory world of business (aka Finance). The irreduciability of material capital goods is what allows them to argue an outsized share of the value of the end product should go to capital.

Chris,

Of the additional $1B in revenue Q-o-Q, most of that is due to 2 months of revenue from the acquired Norbord business. “Only” $300M is from increasing lumber prices, and it looks like all of the increase was due to mark up (unit lumber sales must have been about identical Q-o-Q because the costs associated with producing and selling them was almost identical). See pages 15-16 of the Q1 report you linked.

So,I am with Mark Blyth in the belief this is a short term shock until supply catches up with demand, and there’s a lot of M&A happening right now, so I see the continuation of the breadth regime (of which West Fraser/Norbord is an example).

Discussion on the Real-World Economics Review Blog.

I’ll say. Quite a discussion.

But did that profitability result in differential capitalization compared to other S&P 500 companies?

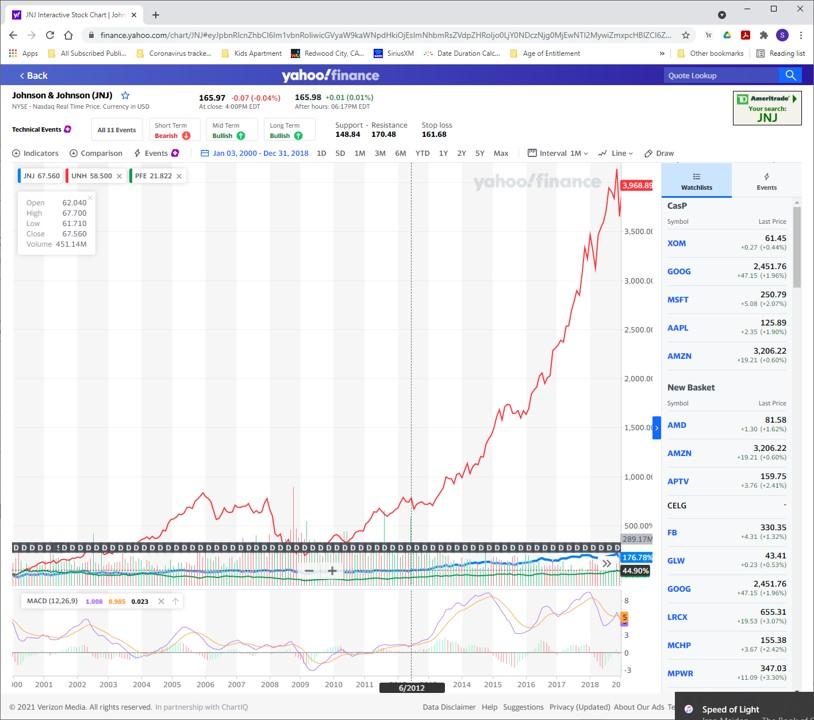

Health insurance provider United Health Care (UNH) may not have been as profitable as pharmaceutical companies, but its share price grew much more (>13x) over the same period (2000-2018), at least compared to the two largest market cap pharma companies today:

Here is a link to a comparison between UNH and the top 5 pharma companies from 2000 until today. UNH’s share price has grown 6000% compared to Roche’s 425% (the largest increase of the 5) in the same period. The S&P500 grew only 188% over the same period.

FYI – it is my understanding that health insurance companies, like all insurance companies, are judged by a different set of metrics than product companies, as insurance companies don’t do anything other than try to maximize the percentage of premiums they keep as profits. Also, regardless of the rate of inflation, healthcare costs go up by 7% a year in the US because the health insurers and providers negotiate annual price increases and lock them in a year in advance. UNH is fine with annual growth, as long as it retains its 15% of premiums as profits.

You focus on analysts, but how well do analysts predict earnings (figure 1, CasP, p. 213)?

Actually, I don’t focus on analysts. I am merely sharing how your capitalization ritual works in real life.

I’ve done investor relations (IR) at three different publicly traded companies, all as an executive officer. What I have shared on this forum is how things worked at every single one of them. I don’t endorse the analysts, who are often 26 year old kids straight out of business school, but they are what they are and they do what they do, as do the companies who have to manage them to ensure there is not too much, or too little, “hype.”

Believe it or not, the future is actually unknowable. The job of public companies and Wall Street analysts is to create the illusion that the future is not only knowable, it is known. Why? Is this illusion a “nice to have” or a “must have” for dominant capital?

Your theory creates an opportunity to ask a lot of questions that otherwise would not be asked, which is why I find it interesting and worthwhile. I’m just trying to provide some practical experience to inform the theory (and to ask better questions).

1. Yes, reduced risk perceptions increases capitalization, but you mentioned findings that were not in James’ work. 2. Yes, of course. Companies do all sort of things, including trying to project next quarter’s earnings. But capitalization tends to look into the deep future, which is unknowable and unverifiable here and now. And I think that, in general, it is these long-term earning expectations that drive capitalization.

1. The second sentence was my own conclusion. James did find that reduction of differential risk led to an increase in differential capitalization “despite falling differential earnings from 1980 to 1994.”

2. If you look at a typical analyst report, their models usually take current earnings (and maybe a year prior) and assume a common annual growth rate over the next 3-5 years. Companies successfully influence that baseline growth assumption all the time, and that’s pretty much all they can do. But it is usually enough unless you have an unusually bearish or bullish analyst, in which case you better hope you have several so consensus is reasonable.

1. James’ work on Hollywood showed that the leading firms didn’t manage to increase their differential earnings. Instead, they reduced their differential risk. 2. Regarding the causal chain between earnings and capitalization (of both interest as debt and profit as equity), I think you might be putting the cart before the horse. Conceptually, capitalization is based on expected future earnings, so that, all else remaining the same, greater earnings expectations –> larger capitalization The thing is that, in practice, capitalization occurs before the future interest and profit are earned, leading to the (false?) conclusion that larger capitalization –> greater earnings In retrospect, firms that see their capitalization increase are driven to accommodate that increase by higher earnings, lest they crash, but the original impetus for that higher capitalization was greater earning expectations.

1. Shouldn’t reducing differential risk equate to reducing the discount rate, effectively increasing (growing) the net present value of discounted future earnings even if the nominal future earnings remain the same? At some point, reducing risk won’t be any more effective than reducing cost as a long term strategy for growing earnings.

2. Companies try to use the quarterly earnings call ritual and follow-up calls with investors and analysts to avoid earnings projections they don’t think they can meet. Nothing hits your stock price like over-promising and under-delivering.

This has turned into a very interesting thread. To return to Brian’s original comments, I think that the law and capital as power are in need of further research. The way I think of it is that Nitzan and Bichler have laid out what they see as the broad goals/methods of capitalism. The legal regime is the primary place where these goals are contested and enacted via property rights.

I, for one, could never be a lawyer because I find the minutia of the law to be incredibly dull. Still, it is a rich area to study. In particularly, I’d be interested in work that compares how different legal regimes relate to capitalization and differential accumulation.

I have been practicing law for most of the last 30 years (with some breaks here and there to focus on the business side of things). I enjoyed law school because I focused on what connected things together (the so-called “seamless web” of the law) and not the small details. Generally, I found law school to be a great place to learn history.

Capital is power because of the law: but for the law creating a separate domain for Finance to rule according to accounting principles, capital as we know it would not exist. Capitalism is its own game within the broader game of society, but the game within the game rules everything.

This problem is methodological and I think that it makes industry/sector research a better starting point to build CasP (not to say that we can’t do more with what we build). For example, when I worked on my dissertation I had an acute fear that I could not put my finger on how Hollywood accumulated through power–hence the metrics, proxies, triangulation. Because if I could not measure how Hollywood accumulated through power, how would I know if my reference to power was more metaphorical than literal?When earnings growth is the imperative, as it is for every publicly traded company, you will always find what you found with respect to Hollywood, regardless of industry or sector. “Dominant capital” (which to me is everywhere and always Finance) has been remarkably effective in making earnings growth the imperative for listed companies. As a former CEO of mine liked to say “If you aren’t growing, you’re dying.”The real question is why is earnings growth the imperative, i.e., what makes growth so important to dominant capital? The answer is in the modern bank-money system, which requires every increasing debt and spending to avoid collapse (and to accumulate capital). This is why I am partial to Tim Di Muzio’s work.May 31, 2021 at 11:55 pm in reply to: A proposition of “ecological antiturst” (as a potential research subject?) #245737This might be my pure delusion, but I think we might need a kind of “ecological antitrust” policies to reduce the size and power of institutions based on, for instance, the complexity of their production and based on the distance of shipment. Of course, this perspective is not something that antitrust law and commercial law currently cover, but I think there are ways that these fields can start to talk about it. (For instance, I think, the “business” protected by the law in fact includes the degree to which it can control and command logistics.)

Brian,

I am currently active in the development of a new battery technology intended to enable all-electric aviation (“AEV”, e.g., an 180 passenger commercial airplane capable of traveling from SF to NY on a single charge). I also hope the technology will allow battery storage to cost less than transmitting power over a grid, thus reversing the current power generation and delivery paradigm (which would substantially reduce wildfires here in California).

The problem with getting to zero carbon emissions is about 30% of current emissions have no economically viable solution, which suggests that we will have to do without (or with less of) the products that result in such emissions. Unfortunately, the primary culprits of these emissions are international travel, international shipping, concrete manufacturing, steel manufacturing and chemical manufacturing. International travel/shipping are the easiest for us to tackle in the near term through AEV, and by limiting international shipping to the delivery of raw materials (no more shipping of manufactured goods).

If we seek to address global warming to fundamentally change the nature of globalism by limiting it to the international transfer of capital, raw materials and IP/information, hierarchies will necessarily be reduced in size because they will be regional, not global, for agriculture and manufacturing and local for energy production (solar, wind and hydro). These days (since the ascent of Bork’s analysis), antitrust laws have been largely reduced to being applied with respect to international competition (e.g, anti-dumping), and to secure low-cost and widespread international licensing and transfer of IP/information, antitrust laws may need to be loosened, not strengthened. For example, competitors in the semiconductor industry may need to share fabrication facilities and basic manufacturing technologies (which they already do to a certain extent, but implicitly through common vendors, not explicitly).

FYI – I am not necessarily a proponent of globalism, but capitalist fear change, and maintaining some form of globalism is probably necessary to drive consensus.

P.S. I view most environmental regulation these days as dependent on Pigou, not Coase. Ironically, the so-called Coase Theorem eliminates private property and thus the entire basis for both liberalism and capitalism.

Thanks, David, for the email!

What is the main thesis of the book [Nitzan and Bichler, Capital as Power (2009)]? Are you trying to show that

1_ The capitalist regime will one day be overthrown as “the masses” become enlightened? (If so, hopefully something better than the communism of the Soviet Union will replace it.)

2_ The capitalist regime should one day be overthrown ?

3_ “The capitalists” will continue to grow in power until they own — and control — everything. And there is nothing that “we, the people” can do to prevent this. Any help you can give me to understand your book would be appreciated. US$ 50 billion).

I would argue “none of the above.” The primary insight of the book is “Capitalism is a mode of power,” and the book uses this insight to present a new framework for thinking about and understanding Capitalism. The book offers no predictions, recommendations or judgments about Capitalism itself.

In context, I understand “mode of power” to refer to a “political” (loosely defined) system that creates and enforces social order. Historically, such systems were merely referred to as a “state,” as Aristotle did. Unlike prior modes of power (and especially states), however, capitalists wield their power covertly and indirectly through the assertion of legal rights such as private property, not overtly and directly through violence as the rulers of a state do, and capitalists do so by encouraging constant social change instead of by enforcing a static social order.

PS. I am also having trouble understanding the term “capitalization”. Do you mean by this term just the “total value” in a corporation (as in the market capitalization of Microsoft is US$ 50 billion).

The Capitalist Mode of Power includes a glossary of terms and defines capitalization as follows:

“Capitalization . Capitalization is the discounting to present value of risk-adjusted expected future income. For listed corporations, capitalization –which is often called market value – is calculated by multiplying the price of one share by the number of outstanding shares. For example, if Facebook has 2.17 billion shares outstanding and one share is currently trading at US$24, then the company is currently capitalized at US$52 billion. But capitalization is also the dominant mathematical ritual of capitalist societies. Anything that generates an income stream can theoretically be capitalized and, in that sense, is part of capital.”

The glossary also defines “mode of power” differently than I do (my definition explicitly equates “mode of power” with politics and “mode of production” with economics, thus refuting the duality of economics v. politics; capitalism is both systems in one):

“Mode of power . The specific architecture of power that creates and recreates a given hierarchical, class society. The notion of a mode of power differs from that of a mode of production: whereas the latter emphasizes production and labour as central to understanding society, the former prioritizes the role of organized power.”

Yap. CasP has plenty of room to expand. In the meantime, here is a small sample of “fine brush” insights into the “underlying mega-machinery of capitalism”: Joseph Baines http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Baines=3AJoseph=3A=3A.html DT Cochrane: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Cochrane=3ADT=3A=3A.date.html Tim Di Muzio: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Di_Muzio=3ATim=3A=3A.date.html Blair Fix: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Fix=3ABlair=3A=3A.date.html Sandy Hager: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Hager=3ASandy_Brian=3A=3A.date.html Ulf Martin: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Martin=3AUlf=3A=3A.date.html James McMahon: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/McMahon=3AJames=3A=3A.date.html Joon Park: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Park=3AHyeng-Joon=3A=3A.date.html Jesús Suaste Cherizola http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/view/creators/Suaste_Cherizola=3AJes=FAs=3A=3A.date.html

I know you love Ulf Martin’s paper, but what is “Autocatalytic Sprawl” and how does it relate to “Pseudorational Mastery”? Stringing obscurae phrases together is not a path to enlightenment for anybody. To get your point across, you should be able to use terms to convey ideas that are meaningful to most people, regardless of education. That is why the neoliberal movement was so successful in reviving capitalism after its many obvious failures, even over Marxism, which itself is relatively easy to understand.

And yes, people like Cochrane, Di Muzio, Fix and Hager have tried to breathe value and meaning into CasP, but despite their best efforts it remains obscure. With the notable exception of Tim Di Muzio’s The Tragedy of Human Development, most CasP efforts seem focused on finding new ways to show capital’s power in this industry or that industry, using this new metric or that new metric. Why should we care if capital is power? How would our lives be different if capital was not power? Why should we care about power at all? (To me, the answer is none of us should be subject to the arbitrary coercive power of another without our consent, which is implied in the case of states but not for private actors.)

Eventually, someone will have to declare CasP’s purpose, and if that goal is not to constrain the power of capital, I don’t see the point.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Scot Griffin.

So, my questions are:

1) From the viewpoint of CasP, does the issue of corporate governance – whether a company should serve only shareholders or serve stakeholders too – matter, in the context of the accumulation of capital and concentration of power?

2) There have been talks on “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)” and now recenlty “ESG” due to more public interests in climate change. From the viewpoint of CasP, *should* corporations (or *can* they )serve the society in general? And how would CSR/ESG look like in reality?

3) How does CasP see Galbraith’s call for countervailing force or stakeholder governance to contain corporate power? Does it have at least some merit? Thank you!

Brian,

Katharina Pistor’s The Code of Capital is a good resource that provides valuable insights into how the law is used to manifest capital’s power, and, as a lawyer who read her book at the same time as my first reading of Capital as Power, I think her book can be used to extend significantly the breadth and depth of CasP theory.

Unfortunately, at this point CasP is primarily a framework for understanding capital as power in broad brush strokes. It’s dialectical approach relies on a aggregate data, which is good for identifying the existence of power (through trends that seemingly defy conventional wisdom) and opposition to that power (through apparent tensions that demonstrate a lack of confidence in obedience), but which offers very little when it comes to actually understanding the underlying “mega-machinery” of capitalism.

There are always exceptions, of course, and I think you might find this article from Jongchul Kim of particular interest because it is consistent with Pistor’s work. I also highly recommend the works of Tim Di Muzio, and in particular his books Debt as Power and The Tragedy of Human Development.

Turning to your questions, I’d argue that CasP is a theory in search of a purpose, or at least a practical application, and people like you and me are free to propose a purpose or application. As a result, “CasP as CasP” has no answers to your questions. CasP is not an ideology, it is an observation that shows its work. Please consider Bichler’s and Nitzan’s response to Debailleul, a CasP paper Prof. Nitzan graciously directed me to in response to some of my own questions. Also see an updated version of the article that triggered Debailleul’s queries.

May 25, 2021 at 1:06 pm in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #2457027. I look forward to seeing your ideas articulated in a systematic piece!

Me, too! Our conversation is helping me understand how to present my ideas better within the CasP framework. I recognize that I often tend to present my ideas in an idiosyncratic way, so gaining a deeper understanding of your theory directly from you should help me “normalize” my presentation.

Let me summarize my understanding of your reply (and add a few comments/observations): 1. Banks do face a repayment risk, but this risk can be eliminated (though I’m not sure I understand how they can eliminate it without foregoing or undermining their expected profit).

Yes, banks do face the risk of nonpayment, but what does that risk really entail and why do they incur it?

Until recently, mainstream economists (including Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman) and central banks insisted that banks acted merely as intermediaries between savers and borrowers, a theory that supported the assertion that economics need not consider money or banks in its models.

Now, central banks openly admit that commercial banks conjure money into existence when they extend credit.

Legally and from an accounting perspective, there ought to be consequences for this admission. First, legally, for years banks committed accounting fraud by claiming to have loaned existing money/capital, which is what allowed them to accumulate the principal tax-free. That’s not “profit,” that’s a form of theft. Second, we know nothing will happen legally, but the accounting rules should be changed, at the very least, to disallow “loans” to be treated as assets except to the extent payments have actually been received. That simple change would not affect the banks’ profits at all, just the timing of if and when those profits accrue as assets on their balance sheets. Personally, I don’t think that goes far enough, as the extension of principal is really the creation of money, a sovereign power. Either (1) banks should not extend credit at interest but instead share an origination fee of 5-15% of the principal as it is repaid, or (2) if lending at interest should continue, 100% of the principal should be taxed while leaving the taxation of interest as it currently is (which would make everybody’s understanding of bank profits true, i.e., banks only profit from the interest, not the principal).

If capital is power, credit money as it currently exists is power laundering through immaculate accumulation.

2. Finance (banks?) creates risk primarily by making ‘bad bets’ (isn’t this true of all capital?). 3. Financial crises are associated mainly with speculation. Finance often initiates these crises through its relation with speculators — but this initiation happens not because it lends to speculators per se, but because it insists they repay their debt — and in ‘hard cash’ to boot (Isn’t all investment/lending ‘speculative’ – i.e. future dependent? Isn’t debt always a ‘collectable asset’ until capitalists realize/admit it isn’t?) 4. My comments suggest that the topic we deal with is both technical and theoretically foundational to negotiate cryptically as we have done here. 5. Your question about my dissertation: perhaps you’ll figure the answer after reading it. 6. “I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics”. That’s your prerogative.

Thanks again for your comments. I am in the middle of writing an essay that I initially hoped to submit for the RECASP competition earlier this year, but I have been struggling with the proper scope of the endeavor. Our conversation has helped me to narrow things down. I should be able to respond to your comments in that essay, hopefully sometime in June.

May 24, 2021 at 11:35 pm in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245699Thanks for the interesting reply, Scot. 1. Bank-originated money. Thank you for the links. I’m familiar with these claims, though I’m not sure how they affect our exchange here. Yes, private banks can create deposits and loans in one fell swoop, but this ability has no bearing on the fact that the loans – be they to corporations, NGOs, governments or individuals – are eventually withdrawn from the accounts in order to be utilized; that they have to be repaid with interest in the future; and that occasionally they are not. Isn’t this last fact a risk for the banks?

There is always a risk of nonpayment, but the banks put nothing of their own (or their depositors’) at risk, and a simple change of the accounting rules could eliminate that “risk,” which the banks only take on because (1) banks don’t want to pay taxes on the “principal” that they did not put at risk in the first instance, and (2) banks want to be able to claim the loans as assets they can use as collateral. Again, the core COP of capitalism appears to be deception.

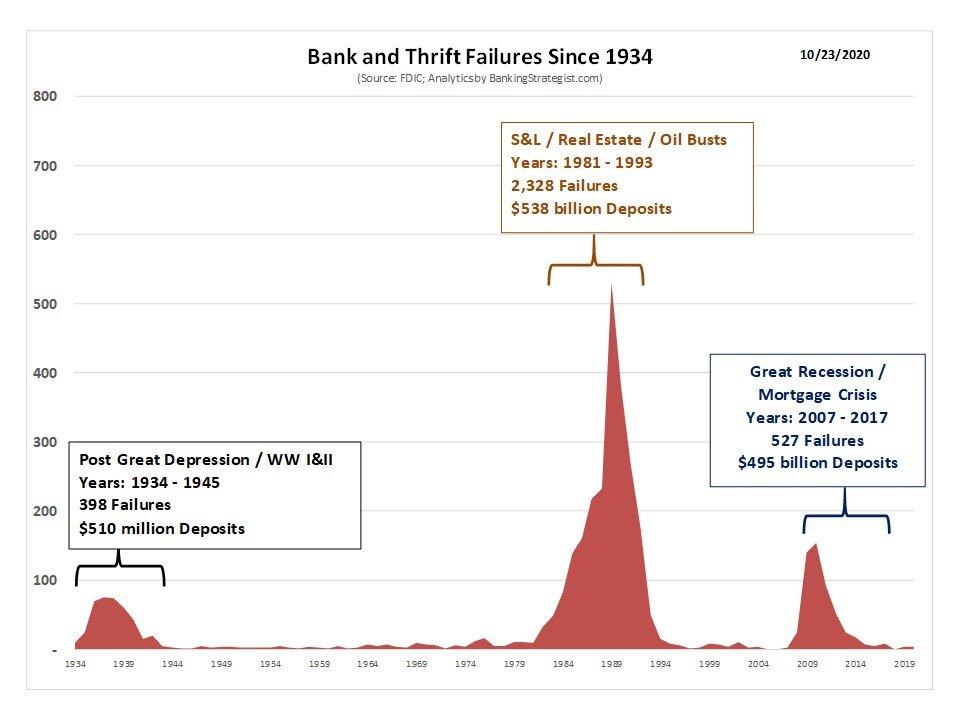

2. The facts. Over the past two centuries, banking crises affected between 5-30% of all countries on an ongoing basis (first figure). In the U.S., banks fail all the time – and occasionally, they fail spectacularly (second figure). Aren’t these crises and failures evidence that banks are risky? [1] Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2008. This Time is Different: A Panoramic View of Eight Centuries of Financial Crises. March. NBER Working Paper Series (13882): 1-124. https://www.nber.org/papers/w13882 [2] https://www.bankingstrategist.com/history-of-us-bank-failures

Yes, Finance creates a lot of risks for itself, and when it loses its bets, society as a whole pays for it. That does not mean that any lending of existing capital/money occurs when banks “loan” money into existence. The Gold Standard never really restrained the Bank of England, for example, who triggered the Long Depression by making bad bets on American railroads in excess of what the Gold Standard allowed (it has been about a decade since I read the late 19th early 20th century text that makes that point, but I can find it again).

I recently read Richard Vague’s A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. (I threw away my hardcover Reinhart and Rogoff a long time ago.) While Vague rightly focuses on excessive private commercial debt as a harbinger of a financial crisis, that debt is usually tied in some way to stock market speculation, i.e., (using a Ghostbusters reference) Finance decided to “cross the streams,” and disaster ensued.

The irony is that banks initiate cascading financial crises not by extending credit to speculators in the first place, but by calling for speculators’ loans to be paid in full when certain money liquidity covenants are triggered. It is the lender’s insistence on being paid in money (as opposed to using other capital assets) that results in fire sales of capital assets that trigger other speculator’s covenants, causing the whole thing melts down.

3. Capitalization. The act of capitalization does not occur in the balance sheet, which is backward-looking. It happens in the equity/debt market which is forward-looking. In this sense, banks are like every other corporation: their ultimate goal is to augment their capitalization by raising their discounted risk-adjusted expected income. That’s why corporations, including banks, are in business.

I disagree with CasP’s definition of capitalization because it does not apply to all capital assets, only stocks. For example, bank deposits, which are a form of capital, are priced by their nominal value. Similarly, the price of a bond can vary even though its yield is known because that yield is less than or more than the prevailing yield of similar bonds (i.e., bond prices reflect discounts or premiums based on whether they have negative or positive differential accumulation with respect to other bonds of the same class and maturity). I have developed my own definitions of capital and capitalization to address all capital assets in a manner that otherwise remains consistent with CasP.

4. Balance sheets. The balance sheets of banks are similar to those of non-bank corporations in that their owners/managers can enlarge them, often at will. Non-bank corporations can do it by borrowing and/or issuing stocks; banks can do it by issuing stocks but mostly by extending loans against deposits (external or self-created). In both cases, the expansion occurs because the owners/managers think it will increase their expected risk-adjusted earnings. But neither banks nor other corporations expand their balance sheets without end. And why not? Because debt leverage and equity dilution are risky.

Balance sheets are very important to Capitalism and may be an innovation that was even more important to the rise and survival of Capitalism than the modern corporation.

But much (if not all) of the risk on banks’ balance sheets is created by the banks’ insistence that banks get to treat the non-existent loan principal they conjure into existence as already-existing capital/money the banks put at risk so the banks can accumulate payments of principal without paying taxes (“immaculate accumulation”). That is, the banks create and embrace the risk to ensure their own differential accumulation. This risk, which is of their own creation, is only exacerbated by the banks’ refusal to accept capital assets other than money deposits as satisfaction of called loans. As a result, I have less than zero sympathy for commercial banks and believe they need to be reduced to public utilities.

By the way, today I started reading your 1992 Ph.D thesis, which is pretty impressive. Given that neoclassical economics insists that power is exogenous to the economy and economics, I just don’t understand how you came to embrace your intuition that inflation is a form of restructuring, i.e. the assertion of power. Trying to quickly follow the through line between your thesis and the 1998 article introducing the concept of differential accumulation did not help me figure out why you chose to take a path so orthogonal to your home academic discipline. I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics. Capitalism transcends prior conceptions of the state as it is agnostic to and capable of subsuming/subordinating all of them by rendering them as little more than bread and circuses for the masses.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Scot Griffin.

-

AuthorReplies