Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

COVID-19 is not to capitalism what the Black Death was to feudalism. Capitalism has survived prior pandemics (see, e.g., the Influenza Pandemic of 1918), and it will survive COVID-19.

The collective action problem that is an existential threat to capitalism, a real stress test, is global warming. Global warming has sparked a civil war within capitalism, with the extractive industries (e.g., mining, oil and gas) on one side, and everybody else on the other. In the U.S., the Republicans generally represent the extractive industries, and the Democrats represent the remaining capitalist industries (including Finance). This division is meaningful because it has shaped, in large part, the American response to COVID-19, which varies greatly depending on which party controls which state. The nihilism of the extractive industries influences Republican policy-making well beyond global warming, and it has deeply influenced the Republican response to COVID-19.

That said, COVID-19 is a stress test on liberal/neoliberal governments, and it is not clear to me that all of them (including the United States) will survive. But capitalism does not need liberalism or neoliberalism (both are just apologetic propaganda for capitalism) to exist. See, e.g., Pinochet’s Chile and Orban’s Hungary.

There is a reason the Republicans are lauding Orban. And there is a reason they have politicized the COVID-19 pandemic. To them, COVID-19 is just a tool to prevent the U.S. and the world from addressing global warming because the actions needed to do so would wipe out the ability of the extractive industries to continue accumulating wealth the way they do today.

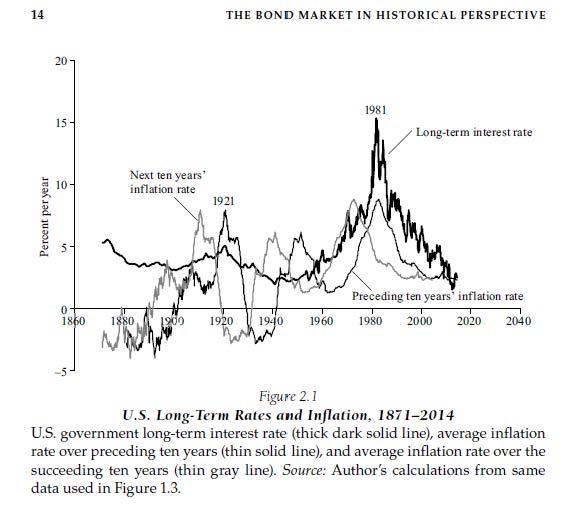

From 1960 until 2000, 10-year US treasury yields appear to have correlated with the average inflation rate of the previous ten years.

How does this relate to the Power Index and/or systemic fear, if at all?

Or is this just what creordering looks like?

From Chapter 2 of Schiller’s Irrational Exuberance:

4. I think the WSJ critique here is misguided. The writer contrasts two examples – one relative, the other absolute: (1) an equal 10% increase/decrease in the stock prices of a very big and a very small company; and (2) an equal $10bn increase/decrease in the earnings of these same companies. In my view, this is a comparison of apples and oranges. Because the very large company has a greater number and/or a more expensive stock price than the very small company, a 10% increase in the price of this very large company has a much lager absolute effect than a 10% increase in the price of a very small company. Market-cap basing helps reflect these absolute differences. This market-cap basing isn’t necessary with EPS, since this measure is already computed in absolute terms (dividing the $ sum of all earnings by the number of all outstanding shares). This is why a $10bn gain/loss of the two companies should be treated equally. Had the WSJ writer complained that S&P weighted equal % changes in prices but didn’t weight equal % change in earnings, then the criticism would have been valid. But as stated, I think it is invalid. 5. I look forward to an empirical analysis of both stocks and bonds that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings, and why changes in the correlation correlate so tightly with the stock price/wage ratio.

4. I just wanted to bring this to your attention just in case it mattered. Again, I am not a statistician, but I was concerned there might be something in how the S&P was doing things that might create a dependency somehow. If you are good with their approach, then I am fine, too.

5. I look forward to somebody doing that, as well. The fact remains that a lot of things in finance started changing around the same time. To me, they indicate aggressive creording, as you say. Capitalists no longer fear the ruled because the ruled think they’re capitalists, too, and they’ve been conditioned to blame their government for their failures, not capitalists. If you accept the phenomenon you’ve discovered as true, regardless of how you label it or what you believe motivates it, it seems to indicate a fundamental change to the capitalist creorder, and if the correlation is increasing with time, maybe that indicates we’re still in transition towards a new steady-state.

In closing, one of the necessary constituent elements of capitalism is fraud. Without fraud, in particular the “normative myths” such as the duality of politics and economics, capitalism would never have been successful. Capitalists indicate in everything they do that they know that the stock market is subject to risk and uncertainty, i.e., they know they can’t just let everything ride and hope for the best, but as long as they can control that to ensure differential accumulation, they don’t mind making less in the near term to ensure steady growth in the long term. What you call “systemic fear” may just be another manifestation of differential accumulation.

A brief follow-up to some of your specific points, Scot: 1. Compounding interest is backward-looking (it adds the interest that wasn’t paid to the balance), so in that sense, it is ‘opposite’ to forward-looking capitalization. I look forward to insight from considering them jointly. 4. Stock index data are often adjusted and spliced. I doubt that in the case of the S&P series adjustment/splicing alters the overall trajectory. As far as I know, EPS and price indices are based on the same stock weightings. 5. I look forward to bond-stock analysis that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings. 6-8. I don’t understand your ‘one question’. Our power index is the stock price/wage ratio. Our systemic-fear index is a correlation between stock price and recent earnings. I cannot see any technical reason for these totally different indices to correlate.

1. I would argue that lending (or, more correctly, extending credit) at interest, whether the interest is simple or compounding, is always forward looking because the simple act of doing so creates future revenue stream (i.e., the interest), the timing and amounts of which are certain and subject only to the risk of non-payment (no need for “hype,” etc.). Capitalization as a process attempts to simulate the simplicity of lending at interest in the presence of uncertainty as to timing and amounts of returns. The “discount rate” used in capitalization as part of a capital budgeting decision-making process is set to the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of the company to determine whether the company makes any money when the costs of borrowing to fund the project are considered. For these reasons, I view capitalization as something that was originally developed as a way for comparing investments in stocks with investments in debt (whether lending directly or purchasing bonds). (I think your 2009 book refers to using discounting methods to determine whether the early payment of debt would actually provide a discount to the debtor.)

4. Here is a link to a blog post referring to how S&P calculated the Index price and the EPS in 2009. EPS was not weighted then, and I have no reason to believe anything has changed since then, and I have downloaded the latest mathematics methodology documents from S&P.

Here is a link to the referenced WSJ article: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB123552586347065675

I don’t have full access to the article, but here are a couple of paragraphs:

A simple example can illustrate S&P’s error. Suppose on a given day the only price changes in the S&P 500 are that the largest stock, Exxon-Mobil, rose 10% in price and the smallest stock, Jones Apparel Group, fell 10%. Would S&P report that the S&P 500 was unchanged that day? Of course not. Exxon-Mobil has a market weight of over 5% in the S&P 500, while the weight of Jones Apparel is less than.04%, so that the return on Exxon-Mobil is weighted 1,381 times the return on Jones Apparel. In fact, a 10% rise in Exxon-Mobil’s price would boost the S&P 500by 4.64 index points, while the same fall in Jones Apparel would have no impact since the change is far less than the one-hundredth of one point to which the index is routinely rounded.

Yet when S&P calculates earnings, these market weights are ignored. If, for example, Exxon-Mobil earned $10 billion while Jones Apparel lost $10 billion, S&P would simply add these earnings together to compute the aggregate earnings of its index, ignoring the vast discrepancy in the relative weights on these firms. Although the average investor holds 1,381 times as much stock in Exxon-Mobil as in Jones Apparel, S&P would say that that portfolio has no earnings and hence an”infinite” P/E ratio. These incorrect calculations are producing an extraordinarily low reported level of earnings, high P/E ratios, and the reported fourth-quarter “loss.”

5. I think it is important to consider the entirety of the landscape of capital assets that make up investors’ portfolios. If you consider the dynamics and interactions between debt and equity markets, it is not difficult to imagine an alterative narrative and label for the “systemic fear index.” Rather than reflecting increasing fear of disobedience of the ruled, it may indicate increasing certainty of their power to command the obedience of the managers/executives. As a way to maintain discipline and ensure management deliver on forecasts, exercising ruthless control over management’s fortunes (which are tied up in stock options and grants) is a great way to do it.

The narrative in the US begins with the destruction of US manufacturing (and its unions) in the late 1970s and early 1980s followed by the easing of consumer credit standards to increase purchasing power even as wages remained stagnant. Extracting interest from the ruled allowed Finance to drive down yields of corporate bonds and commercial lending, which act as a drag on earnings and lead to cost-push inflation. This left the stock market as the only place to seek high yields and increased capital accumulation, which is not a bad thing because the stock market, unlike the credit markets, allows for the creation of new capital without (necessarily) increasing the money supply. Since the stock market is the only game in town, Finance rigs the game to ensure differential accumulation relative to the real rate of inflation.

6-8. I apologize for mischaracterizing the systemic fear index. That was an error on my part.

August 31, 2021 at 12:06 am in reply to: Questions on the schism betwen monetary consumption and material consumption #245997Interestingly, I’ve been having an email conversation with Jason Hickel on this topic. I think the most important thing for degrowthers to achieve is to take the focus off GDP. GDP growth (or decline) just doesn’t matter.

I would argue that GDP growth, more and more, does not represent economic growth but wealth transfer, and I would exclude extractive segments of the economy (e.g., healthcare and higher education) from the calculation of GDP.

Over 60% of healthcare costs are incurred by people over 50. Treating cancer is not something you can get a loan to do near the end of your life expectancy. You have to tap into your existing wealth or take on credit card debt, which can be fobbed onto your heirs.

By the same token, the payoff of higher education increasingly does not justify the cost of taking on high debt levels, a risk that can affect both the children and their families in negative ways. And I say this is somebody who believes that a college education is its own reward and would like to see everybody who wants a college degree given the opportunity to obtain one debt-free. I hate that there has to be a “payoff” for going to college, but that’s the reality we live in, if you have to borrow tens (or hundreds) of thousands of dollars.

There is Congressional testimony from Simon Kuznets regarding the value of GDP as a metric of well-being. You’ve probably seen it before, but if not, I can track it down (I know generally where it is on my hard drive). The money part of the quote is easy to find on Google, but I recall he provides a bit more context in the full testimony.

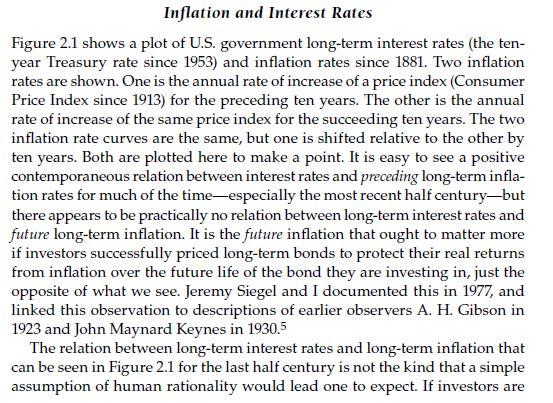

Thank you Scott. Here are some thoughts. 1. The CasP emphasis on forward-looking capitalization has nothing to do with investors/capitalists being ‘rational’ or ‘irrational’. In our view, forward-looking capitalization is a ritual. (Until the early 20th century, it was heatedly debated by investors and theorists, many of whom thought it was fraudulent and that asset prices should reflect backward-looking ‘real’ means of production.) 2. Forward-looking capitalization does not mean that capitalists ignore the past. It simply means that they use whatever information they have — including the past and including recent earnings — to predict future earnings all the way to infinity. 3. I think we agree that the short-term gyrations of last year’s earnings cannot tell us much about their long-term trajectory. So, if investors indeed discount expected long-term future earnings, stock prices should not be correlated with the ups and down of recent earnings. 4. The data in the following chart show that, during the 1880-1980 period, as the forward-looking ritual gained traction, the correlation between price and recent earnings trended down, In the 1950s, and then in the early 1980s, it turned negative.

5. This long-term decline inverted in the early 1990s. Since then, the correlation between stock prices and recent earnings rose more or less uninterruptedly, reaching all time highs recently. 6. This inversion, we argue, represents a breakdown of the forward-looking capitalization ritual, and this breakdown is not accidental. In our opinion, it represents systemic fear – investors’ fear that the capitalization system itself might be unsustainable. 7. As the following chart shows, the entire history of the systemic fear index is associated, dialectically, with the capitalized power of capitalists, measured here by the stock price/average wage ratio: the higher this power, the greater the fear of capitalists that it cannot be sustained, and therefore their greater systemic fear.

8. The correlation in this chart suggests that the future profit expectations of forward-looking capitalists are calibrated by their power: the lesser/greater their power, the smaller/larger the significance of recent profit for their future-earning predictions. 9. This discussion deals with capitalists as a group and in that sense is unrelated to differential accumulation. Hands-on capitalists accumulate differentially by creordering the power underpinnings of their own assets in ways that affect expected differential profit, hype and risk perceptions, while absentee owners do the same by correctly predicting this creordering. The ongoing changes in overall power of capitalists calibrates the way in which their differential efforts translate into future earnings expectations: the greater/lesser this power, the greater/lesser the impact of their current actions-turned-profit on future earnings expectations. 10. And all of these differential processes — although happening here and now, and even though they are affected by the present to various degrees — are focused on the future.

8. The correlation in this chart suggests that the future profit expectations of forward-looking capitalists are calibrated by their power: the lesser/greater their power, the smaller/larger the significance of recent profit for their future-earning predictions. 9. This discussion deals with capitalists as a group and in that sense is unrelated to differential accumulation. Hands-on capitalists accumulate differentially by creordering the power underpinnings of their own assets in ways that affect expected differential profit, hype and risk perceptions, while absentee owners do the same by correctly predicting this creordering. The ongoing changes in overall power of capitalists calibrates the way in which their differential efforts translate into future earnings expectations: the greater/lesser this power, the greater/lesser the impact of their current actions-turned-profit on future earnings expectations. 10. And all of these differential processes — although happening here and now, and even though they are affected by the present to various degrees — are focused on the future.Thank you. Attempting to reply to each point in turn:

1. I agree that what CasP calls “capitalization” and a ritual has become increasingly important to capitalism over the last 50 years, but I believe the original “ritual” was the compounding of interest on credit/loans. Capitalization is basically the inverse of compounding interest. To fully understand capital as power, I think it is important to consider capitalization and compounding together.

2. Thanks. Your clarification was very helpful. I think we are on the same page.

3. Correlation is something I should understand better, especially as it relates to this specific data. My current understanding is that positive, non-zero correlation between two variables indicates some kind of dependency (inter-dependency?) between the two, and the effects of correlation are largely directional (moving up or down together) not necessarily in terms of absolute magnitude.

4. I have some concerns about the SP500 data that I might not have if I were more immersed in statistical analysis. First, the SP500 didn’t have 500 stocks until 1957. Second, the index is curated, removing and adding stocks, as well as adjusting relative weighting, over the years in part, it appears, to maintain its upward trajectory. Third, the index price and EPS data are derived considering using a different number of shares, where index price is sums the weight-adjusted shares of the outstanding float of each company, and EPS is a straight summation of the EPS of all shares of all constituents without weighting. Does weighting a smaller number of shares for one variable but not the other leave something that doesn’t cancel out, thus creating the appearance of correlation?

Regardless of correlation, aren’t there potential causes other than “systemic fear”? For example, what about high frequency trading (HFT) and dark pools, which prevent price discovery and increasingly dominate the number of shares traded each day? What about good old fashioned concerns/fears about the business cycle: the longer a boom continues, the more behavior changes as the perceived risk of a correction grows? And where is there independent evidence that capitalists should fear the ruled?

5. What happened in the bond markets in the 80s and 90s? It looks like the long-term decline of correlation reversed when bond yields began to decline and people piled out of the bond markets into the stock market, which historically have been inversely correlated, right? Considering the stock and bond markets together might help complete the picture.

6-8. Leaving the “fear” label aside for the moment, the ascendance of the stock market and the steady decline of the bond yields since the 1980s should be cause for worry as it implies credit creation may no longer be a useful tool in differential accumulation (at most it helps you tread water). Before, the capitalist had it easy: just pile into stocks when yields fell, and pile into bonds when stock prices fell. Now they only have one lever to work with, and they work it all the time, nervously.

One question: shouldn’t the Power Index and the Systemic Fear Index be correlated when each is Index Price divided by a different variable, i.e., wouldn’t one expect P/x to be positively correlated to P/y, particularly when P is much larger than x and y, even if earnings (x) and wages (y) are likely to be somewhate inversely correlated?

True or false: The systemic fear thesis (“SFT”) is based on the assertion/assumption that a rational investor/capitalist does not consider current or past information in making investment decisions. I believe the sentence as written is “true” and the assertion/assumption is false and has been proven empirically to be so.

My concern is that the sentence, as written, is setting up an impossible situation, where any looking backwards in a period of low systemic fear cancels the thesis. As I see it, systemic fear is a symptom of being able to see a future for differential accumulation. Benchmarking, rolling-averages, reading the Financial Times, teaching important ratios like CAPE3–the past is repeatedly incorporated into investor behavior. The systemic breakdown is when there is little to do with all of this information, other than pin price to past earnings (a rising correlation of P ~ E). A 1980s capitalist can use all sorts of methods to discount future expectations–this is not the direct issue–but they have the confidence to throw future expectations farther from the past.

Item no. 2 of Jonathan’s reply adequately refutes the sentence, thankfully.

Now I need to formulate my next set of questions (or straw man assertions), which relates to correlation and causation (and maybe a little history, as well). I am not a statistician, so I am not in a position to argue whether or not the data show correlation. I accept that they do. I am, however, in a position to question what that means statistically and what that might mean in terms of political economy.

For example, I believe as an historical matter that the ritualization of capitalization did not really begin taking root until the 1970s, after Fama’s efficient market hypothesis, the introduction of CAPM and Miller and Modigliani’s seminal papers on market capitalization. With the advent of cheap computing power in the 1980s, financial modeling became easily accessible and widely disseminated, which may explain the rapid rise of “systemic fear” starting in the 90s. Technology has empowered capitalists to be more vigilant and engaged with their investments than ever before.

As long as there are other explanations for the phenomenon called “systemic fear,” I have a hard time accepting the label. Now, if there were independent evidence that the rulers should fear the ruled, I would feel differently. But here in the US, everybody is distracted by capitalist-created “culture wars,” and everybody seems to believe there is a market-based solution for everything, even when the market is obviously the problem (e.g., housing, healthcare, education). If I’d read the original systemic fear paper back when the Occupy movement was gaining traction, I might have felt differently, as well. Nowadays, even aggressively progressive people like Elizabeth Warren self-identify as capitalists and only offer solutions to make life more bearable for the ruled, not to fundamentally change the system.

True or false:

The systemic fear thesis (“SFT”) is based on the assertion/assumption that a rational investor/capitalist does not consider current or past information in making investment decisions.

I believe the sentence as written is “true” and the assertion/assumption is false and has been proven empirically to be so.

This why I don’t understand the value of SFT except as a way to attack the legitimacy of CasP theory. I mean, what’s the point of “differential accumulation” when all capitalists will wind up in the same place eventually, if they just let it ride and ignore facts as they develop? Never mind the fact that the stock market is cyclical, power (and, therefore) capital, is forever and infinite. Right?

Think about it: the only way you can compare yourself to the average is if you consider past information, but SFT assumes doing so is irrational even as CasP more broadly insists that it is how capitalists acquire power.

I really want somebody to explain to me what I’ve missed or overlooked about this basic aspect of SFT. I have other concerns about the methodology and data, but this issue is fundamental. Models only work (i.e., are scientific) to the extent that their assumptions and boundary conditions hold true, and my understanding of SFT’s assumptions is they are false.

Thanks in advance.

–Scot

Regarding IT products, you may enjoy the following documentary, which begins with the owner of an inkjet printer discovering that the printer was failing because its maker, HP, designed it to incapacitate itself after a specific number of pages were printed.

Here is an article specifically about the conspiracy that gave the documentary its title.

https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-great-lightbulb-conspiracy

To me, manufactured scarcity and forced obsolescence are two sides of the same coin because they both ensure continuous demand to avoid oversupply.

One dimension of sabotage that I don’t think has been addressed is access to credit, which, if severely restricted, leads to deflation (e.g., the Great Depression) which is much worse for society (but not capitalists) than stagflation. On the other hand, if credit is easy to get, differential accumulation goes through the roof (and the wealth gap widens).

Thanks for the reply. You say ¨Unlike prior modes of power (and especially states), however, capitalists wield their power covertly and indirectly through the assertion of legal rights such as private property, not overtly and directly through violence as the rulers of a state do, and capitalists do so by encouraging constant social change instead of by enforcing a static social order.¨ Are you suggesting that some (possibly most or all) of the political unrest — e.g., Democrat versus Republican, BLM, Antifa, Boycott Israel (BDS), etc — in the United States is being fomented by wealthy capitalists? How can capitalists exert power by encouraging civil unrest / social change ? What do capitalists have to gain from an unstable United States? Can you give one or more examples of this exercise of control? — CamelGuy

No, I was not trying to suggest that dominant capital are trying to foment civil unrest, although nobody can rule out that possibility. After all, there is a recent history of right-wing astroturfing in the U.S. (see the Koch-bankrolled “Tea Party”) as well as Fox News and the alt-right media, which are owned or funded by right-wing billionaires and keep their audiences in a constant state of fear and agitation. Antifa is more of a label than an organization, BLM arose organically in response to the extra-judicial killing of people of color, and BDS or some form of it has been around since before I was in college in the 1980s. Nevertheless, each of these recently has been elevated into a bogey man by right-wing media, even though BLM appears to be the only organization that has a substantial power base and is growing.

What I was originally attempting to express was B&N’s concept of a “state of capital,” which they pose as much as a question as anything else. The owner of private property has a right to invoke the state to eject trespassers making the property right itself a threat of violence. The owners of a corporation enjoy a form of sovereign immunity, i.e., limited liability, that human actors in the market do not. The state’s legal delegation of privileges (property ownership) and immunities (e.g., the corporate form, safe harbors, etc.) to dominant capital transfers power from the public sphere to the private sphere, creating a domain of state power controlled by capital.

Turning to your question “what do capitalists have to gain from an unstable United States?” Some of them, like Koch industries and the oil industry have everything to gain because they face losing much of what they have because of proposed climate change legislation. Instability means maintaining the status quo, thus ensuring their differential accumulation.

We really should not think of capitalists as a monolith. In CasP, there is “dominant capital” and there are all the other capitalists, which themselves should be further divided into groups based on common interests. Currently, I’d argue that dominant capital in the U.S. is finance, but the oil industry was a very important part of that coalition not too long ago and remains very powerful. George Monbiot once suggested that Brexit was caused by a civil war between English capitalists.

Broadly speaking, there are two dominant forms of capitalist enterprise. The first could be described as housetrained capitalism. It seeks an accommodation with the administrative state, and benefits from stability, predictability and the regulations that exclude dirtier and rougher competitors. It can coexist with a tame and feeble form of democracy.

The second could be described as warlord capitalism. This sees all restraints on accumulation – including taxes, regulations and the public ownership of essential services – as illegitimate. Nothing should be allowed to stand in the way of profit-making. Its justifying ideology was formulated by Friedrich Hayek in The Constitution of Liberty and by Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged. These books sweep away social complexity and other people’s interests. They fetishise something they call “liberty”, which turns out to mean total freedom for plutocrats, at society’s expense.

Scot– On the Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery: It could also be called something like “The Continually, Unendingly Self-Reproducing Expansion of Society’s Tendency Toward Meritocratic Expert-ification into All Aspects of Life as a Means of Legitimizing its Paradigm of Rule Despite All Evidence to the Contrary” if that wasn’t so long and horrible, but it still wouldn’t directly hit on the fact that the paper is largely about innovations in symbolic representation and Ulf trying to define enormous German words/concepts. I’m of the mind that big ideas sometimes require big words so expressing them doesn’t get overly cumbersome. On why capital being power matters: Life still could look like building physical pyramids for our rulers instead of just pyramids of control. It also means, because capital can’t be anything other than power, that any society with capital will inevitably be a society where people are empowered based on their accumulation of capital. Without capital, power and its expressions will obviously still exist but would need to be mediated through other forms. What those forms might be, however, is tough to say until they’re wrenched into being. Sounds like yet another revolution in waiting. Otherwise, asking what life might look like if capital weren’t power seems hollow, since it is and can’t not be. Ishi/JMC– On films about capitalist development: Have you ever seen Norman Jewison’s 1975 film Rollerball? If not, you should!

Jeremy,

Thank you for your comments. I look forward to further discussions.

I believe that CasP as a whole is actually a “big idea” that should, could and would have a much larger following, if it were expressed in simpler, more accessible terms. Instead, the language around CasP has become increasingly more complex since JN’s PhD thesis, carrying CasP farther away from the masses and general consumption. The increasing complexity of the language is neither necessary nor inevitable, and it is something that I am working on addressing myself (I am writing an essay to submit to the RECASP Journal, and my interactions on this forum are a big help in shaping what I ultimately submit).

My questions regarding why/how capital being power matters were rhetorical and aimed at making the conversation more concrete and less abstract. The individualism of liberalism promises a society free from the existence and exercise of arbitrary power over individuals without their consent. Capitalism claims to be necessary to achieving freedom from arbitrary power, but is, in fact, the vehicle for creating and asserting such power. The power of capital can be (and has been) restrained, and I think it is quite possible to end it over the span of a few generations, provided we address the deceit and ignorance that perpetuates capitalism itself. CasP is the theory that is best positioned to address that deceit and ignorance in the current political environment, which is due to what George Monbiot has declared to be a civil war among dominant capital (which he referred to merely as “capitalists”).

Everybody should watch the original Rollerball.

I found the explanation of the logic of capitalism – capitalization, a process that attempts to derive the “present value” of future earnings with a “discount rate” – described by CasP (Chapter 11.) Indeed, it’s a mathematical ritual, which is, arguably being “arbitrary”, nevertheless consistent and binding, and it’s the logic and working principle of capitalism. I also found Blair Fix’s recent article on it very informative: https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/2021/06/02/the-ritual-of-capitalization/ I think it’s important to address the real functioning of our mode of capitalism, which is monetary: as much as the logic of capitalism mentioned above is real and intact, I think, the dynamics of money is as important as the logic. So I wonder what can be said about the capitalization process and the money creation in the economy. As post-Keynesian economics has elaborated, money is endogenous: contrary to the neoclassical notion of money which is just a medium of exchange used just for convenience, whose stock is physically limited (that can be controlled by either via a loanable funds market or via money multiplier), and thus is just a “veil”, monetary dynamics is real and money is credit whose creation and circulation is ultimately depending on the general expectation of future (as eloquently described by Keynes, mediated via liquidity preference.) Indeed, under our modern banking system, money is created endogenously: money creation is an endless process of double-entry bookkeeping, and when banks provide loans to customers, they create money out of nothing (ex nihilo) by marking the amount of money in both asset side and liability side of their balance sheets. (While still most mainstream economists, legal scholars, journalists, and policymakers adhere to the money multiplier myth, now some central banks, including Bank of England and Bundesbank, (albeit tacitly) admit endogenous money.) I think the (better) purpose of banking system is most well elaborated by Hyman Minsky, who is famous for his “Financial Instability Hypothesis” but who I think provided valuable insights into other issues too, including banking regulation. (For more detailed explanation, you can check articles on Minsky by Jan Kregel: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/121994/1/722271182.pdf; and Minsky’s proposal for “post-Glass-Steagall” banking regulation https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/hm_archive/72/) For Minsky, banks are beneficial as long as they contribute to the “capital development of economy”, which means a broader advancement of economy, including maximizing the level of employment and an equitable distribution of income. To achieve this, in line with the post-Keynesian view of money, what Minsky identifies as the fundamental banking activity is “acceptance”: deposit creation following guaranteeing that the debtor is creditworthy. Indeed, banks basic activity is the creation of their own liabilities that are used to “guarantee” and acquire the liabilities of enterprises. These liabilities issued by banks then can be used for investment, but in this process their liquidity and their ability to be substituted for (or accepted as) legal tender remains crucial. Liquidity creation for financing capital development thus is fundamentally connected to the payment system, and here rises the problem of the “two masters”: potential losses from loan creation threatens the stability of payment system. So the core goal of banking regulation, Minsky identifies, is insulating the health of payment system from potential adverse effects of “credit enhancement.” Even when it comes to capital markets – stock markets, MMMFs, – purchases of assets are financed by banks’ acceptance of broker-dealers’ inventory as collateral, and therefore the “liquidity” provided by primary/secondary markets is ultimately dependent on the liquidity generated by deposit-issuing banks (as we all well witness the subprime crisis, and recently, the Gamestop saga). (Here, what Minsky identifies as the problematic tendency of financial capitalism, as elaborated via his FIH, is that entities, after a prior crash, overall increases risks, taking more fragility – feeling “euphoria – on their balance sheets, and ultimately due to the accumulated fragility the cost of borrowing increases, ending up with a crash. This applies to banks too, in that banks increasingly, instead of basing their “acceptance” on the profitability of enterprises, base it on the market price of assets (and the extent to which they can be sold at securities market), and increase off-balance sheet risk-taking activities. His solution to this destabilizing nature of monetary capitalism is establishing a “narrow-banking” system, based on that first proposed by Henry Simons. In his proposal, instead of requiring that banks always maintain 100% reserves as proposed by Simons (which anyway cannot control money creation), while continuously providing liquidity via central bank and deposit insurance, banks are required to *always* go through discount window, so whenever they creates a loan they have to submit it to the central bank in exchange for liquidity. By doing this, while still enabling capital development, central authorities can have a far better sense and oversight on the status of banking system. Of course, this indeed limits money creation and poses a threat of deflationary tendencies. To maintain full employment a functional finance-level government spending is required, and in this context Minsky called for an employer-of-the-last-resort scheme, which now is called a jobs guarantee.) I recently read a paper “Capitalized money, austerity and the math of capitalism” published recently by Tim DiMuzio and Richard Robbins, in which the authors try to connect CasP and endogenous money. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0011392119886876 As the authors put,

“…the act of capitalizing an income stream is the primary act made by capitalists or investors and one of the major features of this ritual is that income generating assets… the dominant owners of banks are capitalizing a very special power unique among the corporate universe: the power to create new official money as credit/debt bearing interest as well as issue fines and fees.” “A future research agenda in the capital as power tradition would examine how bankers specifically use their power to generate earnings… The question is who primarily benefits from the accumulation and the rising capitalization of commercial banks?”

I think much more about the Casp/capitalization and endogenous money can and should be investigated, and here are some question that I have. 1. Can it be said that the deposit/loan creation process or Minsky’s “acceptance” also involve the logic of capitalism – deriving the “present value” of future earnings with a “discount rate” – that capitalization of other assets has (in a sense that, for instance, bankers calculate the profitability of projects or debtors when that make loans?) 2. How would or does exactly endogenous money participate in the process of capitalization? We know, as I wrote above, liquidity of capital markets too depends on bank liquidity, but does it just have some indirect effects or does it have some direct involvement in capitalization of assets? 3. As CasP explains, earnings are a matter of exercising power – “creorder” – across society. How do banks do it exactly?

For a more complete treatment of endogenous money from a CasP perspective, see Di Muzio’s and Robbins’ books Debt as Power and An Anthropology of Money. While both books predate the article you cite, the books contain much more detail (obviously).

From my perspective, credit begets money which begets capital. That is, endogenous money is the original source of capitalist power, and it is the reason for capitalization, which is a secondary “ritual” for determining whether the compounding interest (aka “the yield”) associated with a particular capital asset is greater than the rate of inflation (which is ultimately caused by endogenous money). Accumulating money as “capital” in the financial system does you little good if its value is inflated away due to how endogenous money works, so capitalists figured out a way to create new capital without creating new money.

As Jonathan has explained to me elsewhere on this forum, Bichler and Nitzan do not believe there is an “ultimate” or “primary” source of capital’s power. While that may be true now, capitalism is something that developed over time. It did not leap fully formed from the mind of Adam Smith. The simple fact is that credit is neither capital nor money, i.e., when a commercial bank extends a “loan” it is not lending money, it is extending credit, and thus it does not put existing money (i.e., capital) at risk, notwithstanding the fiction supplied by accounting rules. Thus, the only value (personal commitment) in the loan transaction is the debtor’s promise to “repay” the loan plus interest, something he will not be able to do unless other people take loans, too. I call the “repayment” of loans “immaculate accumulation” because the fiction of accounting rules allows the “lender” to pretend the principal of the loan was its money/capital at the time of the loan, thus avoiding taxation of the principal altogether. All capital began as indentured servitude.

But once you’ve accumulated capital without putting any capital at risk, why would you put the capital you’ve accumulated at risk unless you can secure yields greater than the rate of inflation (or better), thus ensuring the continued process of accumulation (all capital accumulation is necessarily differential accumulation because of the inflation caused by endogenous money) ? That’s the conundrum the ritual of capitalization solved, i.e., the capitalization of future income streams of capital assets was a solution to the inherent instability caused by endogenous money, which demands exponential growth due to compounding interest.

Hi Chris: 1. From power to inflation, or from inflation to power? In my view, the interesting question is not the effect of power on inflation, but rather what inflation can tell us about power. From our CasP perspective, modern power is observed as a quantitative relationship between entities. In capitalism, the ultimate manifestation of this relationship is differential capitalization. You can also examine the components of this power, one of which is differential prices (and their rate of change — namely, differential inflation). From this viewpoint, it makes little sense to say that ‘a lack of workers’ power prevents a rise in future inflation’, simply because nobody knows the future pricing power of workers. Instead, I think it makes more sense to say that the fact that there is currently only limited inflation suggests that workers have limited power and therefore are unable to help fuel it here and now. 2. Absolute versus differential inflation From our CasP viepoint, inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional process. This means that what matters is not the absolute but relative rates at which prices change. Furthermore, the redistributional patterns of inflation may or may not correlate with its absolute levels. This is something that can be deciphered only through empirical research. (For more, see Inflation as Restructuring.) 3. Do asset prices fuel inflation? Over the longer haul, higher asset prices need to be ‘validated’ by higher profit (and/or lower risk and normal rates of return), and profit can indeed be increased by inflation. But for that to happen, capitalists must be able to raise their differential prices, and I doubt that this ability is connected to asset prices as such. 4. Does low inflation means more M&A? In our opinion, the answer is no. In our work, we argued that differential accumulation depends mainly on M&A and stagflation, and that the conditions underlying these two processes are contradictory, so they tend to move counter-cyclically to each other. However, these tentative observations do not mean that there must be either M&A or stagflation. Instead, we simply suggest that at least one of these processes is required for differential accumulation, and that if dominant capital is unable to achieve either, it will end up with no differential accumulation or might suffer differential decumulation.

Jonathan,

In your study of inflation, has it ever been proven that inflation is caused by increased money supply (e.g., the Friedman monetarist argument)? Generally, it would seem that if you put more money in the hands of people who save it, they would simply save more of it, and if you put more money in the hands of people who spend it, they would buy more things, not pay more for what they already buy.

That being said, here in Silicon Valley it is pretty clear that real estate prices (and, therefore, rents) are driven up by easy money from successful IPOs, but usually it seems like inflation is due to price-push or simple mark-up. (I don’t deny supply/demand shocks cause temporary increases in prices, but don’t know if that counts as inflation if the increases aren’t sticky.)

I don’t mean to begin a debate on this issue, just a couple of notes: 1. I don’t think economists think capitalists accumulate any given capital good. Obviously, individual capital goods depreciate. But in the view of economists, capitalists not only replenish the overall capital stock, they also cause it to grow. For them, one of the key hallmark of capitalism is a growing physical capital stock overall made of an-ever shifting array of capital goods and measured in value-read-money-in-‘constant-prices’ (figure below). 2. One has to distinguish accounting from so-called economic depreciation. Accounting depreciation is determined by accounting rules. So-called economic depreciation is determined, supposedly, by the (productive) value of the capital good. In practice, national accounting statistics measure depreciation differently that company accountants.

I don’t mean to begin a debate, either. I was just trying to make sure my point was being understood and looking for any guidance or understanding you and others might offer. Your comments were helpful in clarifying things for me, which should allow me to make my argument better.

Ultimately, “capital stock” seems to be a vague concept that continues to exist solely so that economists can gesticulate and yell “ta-daaaa” in justifying capitalists’ outsized distribution of value. They’ve taken an accounting rule that grants a tax benefit and turned it into an economic parlor trick that cannot be justified because capitalists themselves don’t measure their performance that way. If there is a conflict between accounting and economics, accounting must win.

Jonathan,

If neoclassicals and Marxists want to assign a portion of the value of an end product as arising from the capital goods that helped produce them, they can do so by dividing the depreciation for a period by the number of end products produced in that period to get the per unit contribution of the capital goods.

Regardless, capitalists depreciate the cost of their capital goods over time as an operating expense to smooth out their profits taxes. From an accounting perspective, there is no way around the fact that capitalists consume their capital goods, they do not accumulate them.

If economists want to theorize a different system in which capital goods are accumulated (which I don’t think they have to do, they can just admit that depreciation, amortization and depletion are ways to reflect the contribution of capital to an end product), that system is not capitalism. If they do choose to do the right thing and look to accounting tricks like depreciation to understand capital’s contribution to the cost of the end product, then the contribution of capital goods in all cases reduces down to monetary units, but I don’t know if that tells us anything about the value of capital’s contribution.

Personally, I think the reason why they insist on capital being a material thing is they want to avoid admitting that money and finance are central to capitalism. They want to continue in a world where physical commodities are bartered and no money exists, thus keeping the discussion in the cooperative world of industry and avoiding even acknowledging the predatory world of business (aka Finance). The irreduciability of material capital goods is what allows them to argue an outsized share of the value of the end product should go to capital.

-

AuthorReplies