Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

December 24, 2022 at 12:37 pm in reply to: Effective Discount Rate or the Reciprocal of the Trailing P/E #248789

Thank you for your replies, Scot.

Questions drive thinking, so I thought it was clear that, in saying that you asked many questions but that it wasn’t always clear why, I didn’t criticize you for asking them. I simply meant that I, personally, didn’t understand the reason behind them.

Let me try to clarify my thinking here.

1.

As I see it, the rate of return at any point in time is a backward-looking straightforward computation of the rate of change of the asset’s price (or total return, as the case may be).

By contrast, the discount rate at which future earnings are capitalized to give an asset its price is a much more slippery forward-looking construct. In my work with Shimshon, we suggested two things: (1) that in the mind of capitalists this rate is the product of a ‘normal rate’ common to all investments and a ‘risk coefficient’ unique to the asset in question; and (2) that both quanta vary over time and across investors and can be known only by asking them (finance manuals don’t count here, since investors are free to ignore them).

With this conceptual difference in mind, the rate of return and the discount rate will be the same only by fluke.

2.

The positive long-term U.S. correlation between stock prices and trailing earnings shown in Figure 7 of our ‘CasP Model of the Stock Market’ is backward-looking and therefore cannot tell us how capitalists set asset prices looking forward.

3.

Contrary to your interpretation, we – Bichler and I – do not argue that the trailing E/P ratio is the effective discount rate. Our claim, rather, is that capitalists change the earnings they discount depending on their power relative to workers and their systemic fear. When capitalists are less powerful and more confident, they follow their dominant ritual and tend to discount expected future earnings; when they are more powerful and less confident, they tend to abandon this ritual and discount trailing earrings. The purpose of the bottom panel of Figure 7 and of Figure 9 in our ‘CasP Model of the Stock Market’ was to substantiate this proposition.

4.

Firms with similar backward-looking data can be priced differently – and yield different rates of return — because forward-looking capitalization pretends to see a future that isn’t necessarily the same as the past.

5.

You seem to suggest that finance is somehow separate from and perhaps more important than economics, and maybe you are right. In our view, though, they are not separate but integrated. I think we agree that to understand capitalism we must understand finance, among other things (in our case, because finance is the main architecture of capitalized power). But in our opinion, finance has no theoretical underpinnings of its own. Complex as it may look in practice, finance is a ritualistic derivative of mainstream economic reasoning (or, as an erudite late friend of mine once bluntly opined, ‘it’s not even a “branch of knowledge”’.)

6.

You argue that saying that ‘capital is power’ is ineffective as saying that ‘water is wet’. Somehow, I doubt you really mean it. Researching and demonstrating the ways in which capital is power helps undermine prevailing political-economy and create a new way of understanding and resisting capitalism. The fact that we personally seldom engage in ‘policy recommendations’ is because, at this point, we don’t feel there is anyone to recommend policies to. But you and others are more than welcome to do so.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

December 22, 2022 at 8:30 pm in reply to: Effective Discount Rate or the Reciprocal of the Trailing P/E #248778Scot,

You ask many questions, but it isn’t always clear why.

Obviously, capitalization/discounting/compounding can be made as complicated as you like, but in my mind, the purpose of analysis is to achieve the very opposite — i.e., to simplify. How much to simplify depends on the concrete subject of analysis, which you are yet to specify.

1. Regarding discounting with current known earnings as opposed to expected future earnings. In our 2009 book Capital as Power and later in our 2016 ‘CasP Model of the Stock Market‘, we showed that, over the very long haul, capitalization is tightly correlated with current earnings. This tight correlation is shown in the top panel of this U.S. figure from our ‘CasP Model’.

However, the bottom panel of the chart demonstrates that, over the short run (one year), the correlation between current earnings and capitalized values varies greatly, ranging between +0.6 and -0.2. In other words, in the shorter run, capitalists are very shifty.

2. What causes these changes in the impact of current earnings on capitalization? Our tentative answer was that these shifts depend on the extent of capitalized power (relative to workers): the more powerful/weaker the capitalists, the greater/smaller the correlation. The validity of this claim is shown by the chart below, which correlates capitalized power with the short-term correlation between current earnings and capitalization (taken from the previous chart).

In our work, we speculated that power is bounded. In our view, this bound means that the greater the power, the more frightened capitalists become about their ability to sustain it, and therefore the greater their reliance on visible earnings here and now when capitalizing the future. This is why we labeled the short-term earnings correlation with capitalization the ‘Systemic Fear Index’. (For more on these issues, see Baines and Hager (2020), McMahon (2021) and the work by Fix (2021) that you cite.)

3. On the extent to which capitalists must peer into the future to capture the bulk of their earnings from here to eternity, see our ‘Capitalist Degree of Immortality’ (2021). The chart below shows these computations for various levels of (r–g), where r is the discount rate and g is the geometric long-term growth rate of earnings. It turns out that, under rather normal condition, the capitalist gaze doesn’t have to extend beyond a few dozen years….

Thank you Scot.

Perhaps you mentioned it somewhere in the thread, but it is only now that I realize you define revenues = sold capital + sold output. Since this definition is rarely if ever used either in practice or in accounting pedagogy, I won’t be surprised if others were perplexed by your derivations as I was.

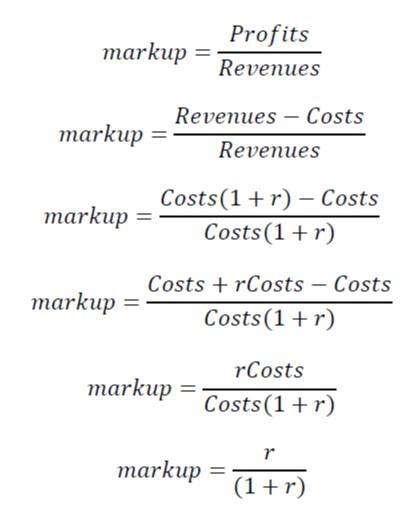

Unrelatedly, there seems to be an error in footnote 20 on page 241 of Capital as Power (2009). To achieve a target return of 20%, you need a markup of 16.67%, not 10% (markup equals r/(1+r)), and 16.67% is what you get when you divide $200M in profit by $1.2B in sales (2/12 = 1/6 = 16.67%) on an initial investment of $1.0B.

Yes, there is a mistake here, but not the one you refer to.

I don’t have the book by Kaplan et al. with me, but if I recall correctly, they define the markup = profit/cost. Our mistake was to use their definition in the footnote without noting it was different than the one we used in the text. In any event, thank you for pointing it out.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Scot.

I think we are talking past each other. Accountants distinguish between capital invested and the rate of return on the one hand, and the cost of items sold and the markup on the other, such that:

1. rate of return = profit / capital

so: profit = rate of return * capital

2. markup = profit / cost of items sold

so: profit = markup * cost of item sold.

***

In your notes, you say that:

3. profit = rate of return * cost of items sold

Unless I made a mistake somewhere, for this last equation to be true, cost of items sold = capital, which normally isn’t the case.

December 19, 2022 at 11:38 am in reply to: Proximity to Legal Authority as a Measure of Power #248754Thank you Pieter for the useful clarification.

When they first emerge, ideas and research projects often seem opaque and ‘problematic’, which is only understandable given that they are new.

A thought: perhaps you can think of the relation between capitalized power on the one hand and ‘proximity to legal authority’ (however defined) on the other non-linearly: As proximity decreases capitalized power increases as you describe, but only up to a point. After that point, when we’ve gone past the legislators, pork-barrel interest groups and the big capitalist entities and reached the underling population, lower proximity goes with lower power.

December 16, 2022 at 11:40 am in reply to: Proximity to Legal Authority as a Measure of Power #248741Counterintuitively, the most power is not held by those with direct access to the creation and re-shaping of law, but rather by those with influence over the law-makers.

In our CasP work, we tend to start with capitalized power — a concept whose magnitudes, we argue, are readily observable through differential capitalization, earnings and risk — and then correlate changes in this capitalized power with its alleged determinants, including policies/legislation.

Your notion of ‘proximity to law’ could be useful in this inquiry, because, in capitalism, the law is often a far more effective regulator of power than convention/influence, violence and illegal action.

The problem is that ‘proximity to law’ doesn’t have an easy-to-measure metric, and that is partly because the very notion of ‘distance’ here is ill defined, if not totally open-ended.

For example, in what sense can we say that legislators of intellectual property rights are ‘closer’ to the laws they draft and vote on than the people, entities and processes whose pressures they are subjected to and whose impacts their actions often mirror?

- This reply was modified 2 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Julien.

1. Our Systemic Fear Index measures the short-term correlation between stock prices and current EPS. We argue that this measure indicates the extent to which asset pricing deviates from the key ritual of capitalizing expected future profits, and that this deviation indicates systemic fear because it shows the extent to which investors doubt their own central compass (A CasP Model of the Stock Market, 2016).

2. The VIX index is a short-term approximation of expected stock-price volatility (30 days to 1 year, depending on the measure).

Although both measures are related to fear, the nature of their respective fear seems different. The first measure is long term, focusing on very limits of capitalization, the second short term, focusing on stock price volatility in the near future.

Perhaps there is reason for them to correlate, though that reason doesn’t seem obvious on the surface.

Thank you Rowan and Pieter for your interesting interventions.

I believe that the notion that power is both the means and end of accumulation was central to CasP from early on. In fact, it was the motivating force for formulating CasP in the first place.

For a recent articulation, see our 2019 piece, ‘CasP’s “Differential Accumulation” versus Veblen’s “Differential Advantage” (Revised and Expanded).

Scot,

If I understand you correctly, you use r to denote the discount rate, which is distinct from the markup, representing the ratio of profits/revenues.

To me, the discount rate r denotes the rate of return (i.e., the rate at which the entity’s assets grow).

- Do you share this view? If you do, why is your following expression valid: revenues = Cost (1 + r)

- If you don’t share this view, what do you mean by the discount rate?

Scot,

Apologies if I misinterpreted your intention. The truth is that I read your long reply to my 8 points, but found myself lost in its details. I also didn’t see an explicit retraction of you original argument that capitalists determine their profit — but, again, there are many moving parts in your reply, so maybe I didn’t understand it properly.

Instead of answering each of your individual points, let me try to digress our view and suggest how it might differ from yours (as I understand it).

Capitalization is given by:

1. K = expected future earnings / discount rate

The right-hand side of this expression can be decomposed into to 4 elementary particles

2. K = (future earnings * hype) / (normal rate of return * risk)

Power-driven capitalists try to augment their differential capitalization (marked by the .d extension) (Note that, because the normal rate is common, its differential value normalizes to 1 and drops from the equation.):

3. K.d = (future earnings.d * hype.d) / risk.d

***

POINT 1. When Eq. 3 is applied to a capitalized entity or group of entities, every element in it represents a distinct aspect of the power of that entity: the future earnings it will receive relative to those of the benchmark, the hype it can create relative to the benchmark, and the risk it can keep low relative to the benchmark, all contribute to its overall capitalized power relative to the benchmark.

From this viewpoint, the differential discount rate (which reduces to differential risk in this formulation) is distinct from differential future earnings and differential hype and therefore has to be treated as only one aspect of power. This conclusion differs from your notion, as I understand it, that, because pricing supposedly relies on discounting, all power can be reduced to the discount rate.

POINT 2. In our view, none of these elementary particles is set exclusively by the entity owners themselves. Instead, these particles are determined by the power conflicts in which the entity is embedded and on which it acts. Thus, differential future earnings, even if greatly influenced by the differential power of the entity, are meaningful only as a conflictual relation with the power of other entities and processes who boost/reduce it (including workers, governments, customers, criminals, culture, wars, etc.). Similarly with differential hype and differential risk, which the entity can alter in one direction but others can change in another.

The result is that capitalized power — which we understand as the quantitative differential representation of many qualitatively different conflicts — is not a top-down dictate of the powerful, but an ever-changing culmination of an ongoing conflict that spans society at large. Capitalists and the entities they own are at the top of the capitalized hierarchy, but their position in that hierarchy as well as the very structure of that hierarchy are constantly changing because power always invites and is exercised against opposition (Ulf Martin’s autocatalytic sprwal).

POINT 3. These considerations might serve to explain why CasP puts so much emphasis on theoretically informed empirical research. Without such research, we cannot decipher — and simplify — the complex trajectories of differential capitalization nor understand the underlying qualitatively different processes that drive those trajectories. Without this deciphering and understanding, our equations and theories remain empty shells at best and misleading corps at worst.

Scot,

I think the issue here is not only whether we can write the equations correctly (which often we don’t), but also – and perhaps more so — whether the equations justify our conclusions.

You write that:

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits.

I think this interpretation is fundamentally wrong.

In and of themselves, capitalist expectations of profit, the ex-ante discount rate used to concoct these expectations, and the impact these expectations have on how much they spend on inputs, do not and cannot determine, let alone ensure, actual profits.

It seems to me that your claim here is not only unrealistic, but also self-contradictory.

Imagine every potential capitalist expecting his/her own profit into existence. This mana-from-heaven magic will make everyone an instant, insatiated capitalist, bring their individual expectations into conflict with each other, and pretty much ascertain that their actual profits will differ from what they expect.

In my view, discounted values do not generate power. Instead, it is power that generates discounted values.

But we can agree to disagree.

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits. See equation 6, below.

Scot,

That’s a clever way of presenting your point, but I don’t think the point itself is correct.

1. What capitalists agree to pay workers certainly depends on their profit expectations, but this dependency is not what your equations express.

2. The discount rate is what investors use to capitalize expected future profits. In your equations, though, r is not the discount rate (the rate of growth of capitalization), but the profit markup over costs (assuming all costs can be expressed as wages).

3. Moreover, the way you express it, r reflects not the intended markup, but the realized one.

4. The realized markup – and therefore actual future profit — is neither at the capitalist’s discretion nor knowable beforehand. It depends on how much capitalists will be able to sell in the future, which is anybody’s guess (and the reason why profit forecasters are almost always wrong).

5. Since capitalists don’t know their actual future profit, they cannot set current wages as a function of that profit.

6. By definition, the wage bill is the product of the wage rate and the level of employment. In general, capitalists control the level of employment — but, in my view, they don’t set the wage rate, which is the result of historical conditions and an ongoing, complex power conflict within the firm and across society. Expected (though not actual) future profit is merely one element of this conflict.

7. For Kalecki, the markup reflects capitalist power. But this reflection is ex post, not ex ante. The discount rate, by contrast, is set ex ante, not ex post. I think it is erroneous to treat them as if they were the same.

8. Perhaps it will be useful to try to express your equations in ex-ante terms (rather than ex post), using the discount rate (rather than the markup).

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

“power is confidence in setting the discount rate,” or, more simply “power is the ability to set the discount rate.”

1. I think we need to distinguish between individuals and groups who determine the discount rates they apply when trying to price expected future earnings (me, Elon Musk, JPMorgan Chase) and the average discount rate prevailing in society. If we take the individual perspective, my power is the same as Musk’s and JPMC, since all of us are free to set our own discount rates as we see fit. If we take the average perspective, then there is no singular entity or group to associate this power with, since the average discount rate is determined by the shifting structures of capitalism.

2. By saying that power is simply ‘the ability to set the discount rate’, you seem to imply that the power of any given entity — me, Musk, JPMorgan Chase — is independent of its (expected) profit. Do you really mean that?

Thank you, James. The 602-page doorstopper is on its way to the bookstores, though, for some reason, the publisher’s book page isn’t up yet.

The book presents and situates CasP theory and research — our own as well as that of others — within the broader evolution of political economy. Some of this material has already appeared in English, but much of it hasn’t, so a translation would be nice. Whether we will do it is another matter….

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

In his interesting 2010 book, Misplaced Generosity. Extraordinary Profits in Alberta’s Oil and Gas Industry (Edmonton, Alberta: Parkland Institute, University of Alberta), Reagan Boychuk offers an account of Alberta’s oil and gas revenues, costs and profit, plus imputations of ‘normal’ and ‘excess profit’. (Twitter thread)

The computations/imputations are built from the bottom up – i.e., they are based on estimates of the industry’s output, average oil/gas selling prices and investment and production cost, so, on the face of it, they reflect the business performance of Alberta’s oil and gas industry — and nothing else.

But here is a question: output levels are collected at the provincial levels, as are selling prices (I assume). But capital and operating costs probably come from the companies themselves, and since these companies are often large transnationals rather than Albertan only, it is hard to know the extent to which their data reflect local operations ‘uncontaminated’ by transfer pricing.

-

AuthorReplies