Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Adam,

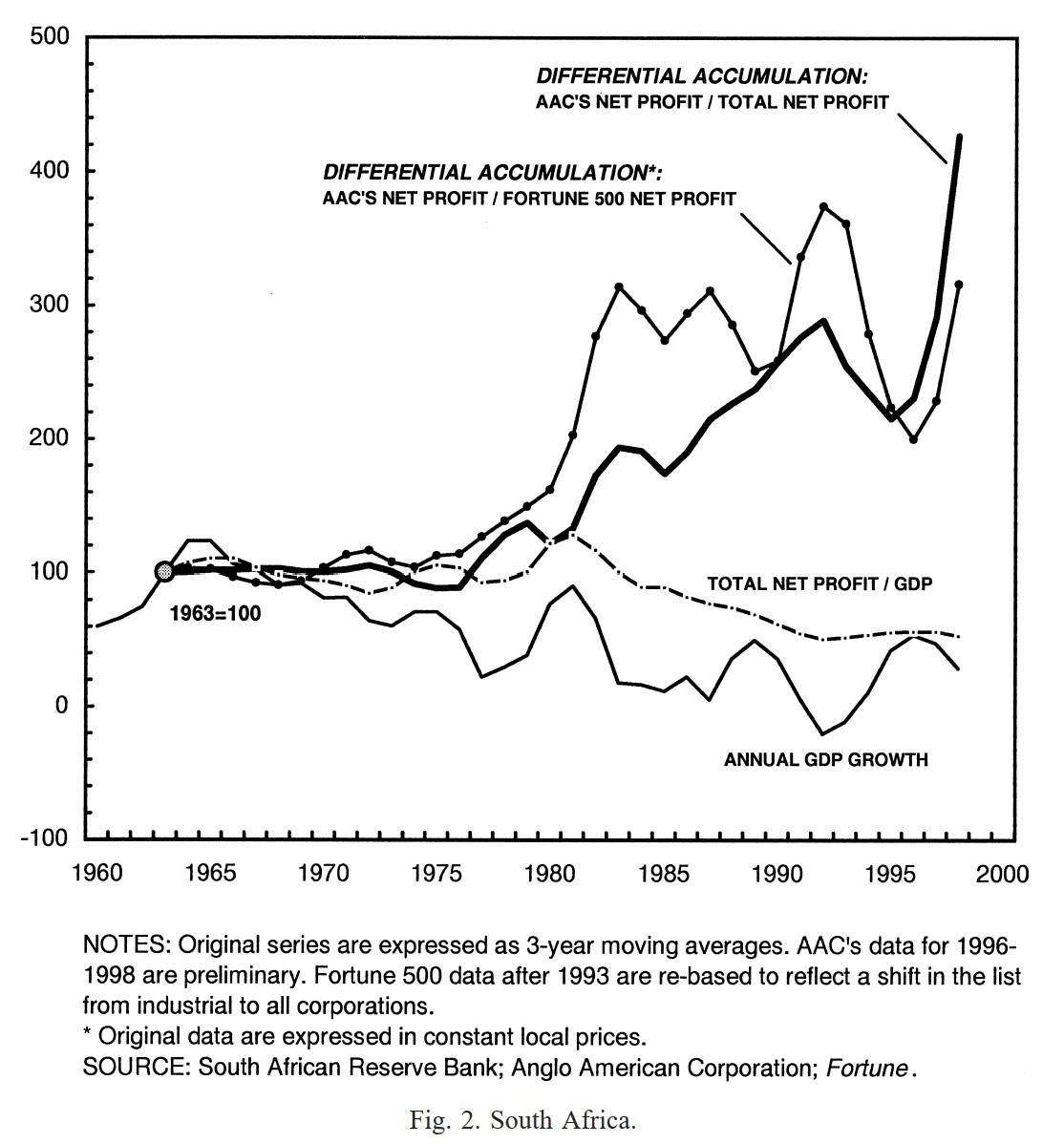

In South Africa, growth was negative in the 1990s, and you cannot compute the log of non-positive numbers. Also, the numbers in South Africa were not growing exponentially as in Israel.

Adam,

Regarding which indices to use, I think Blair’s advice is sound. Usually, more evidence makes your case more robust — although too much evidence can also clutter it.

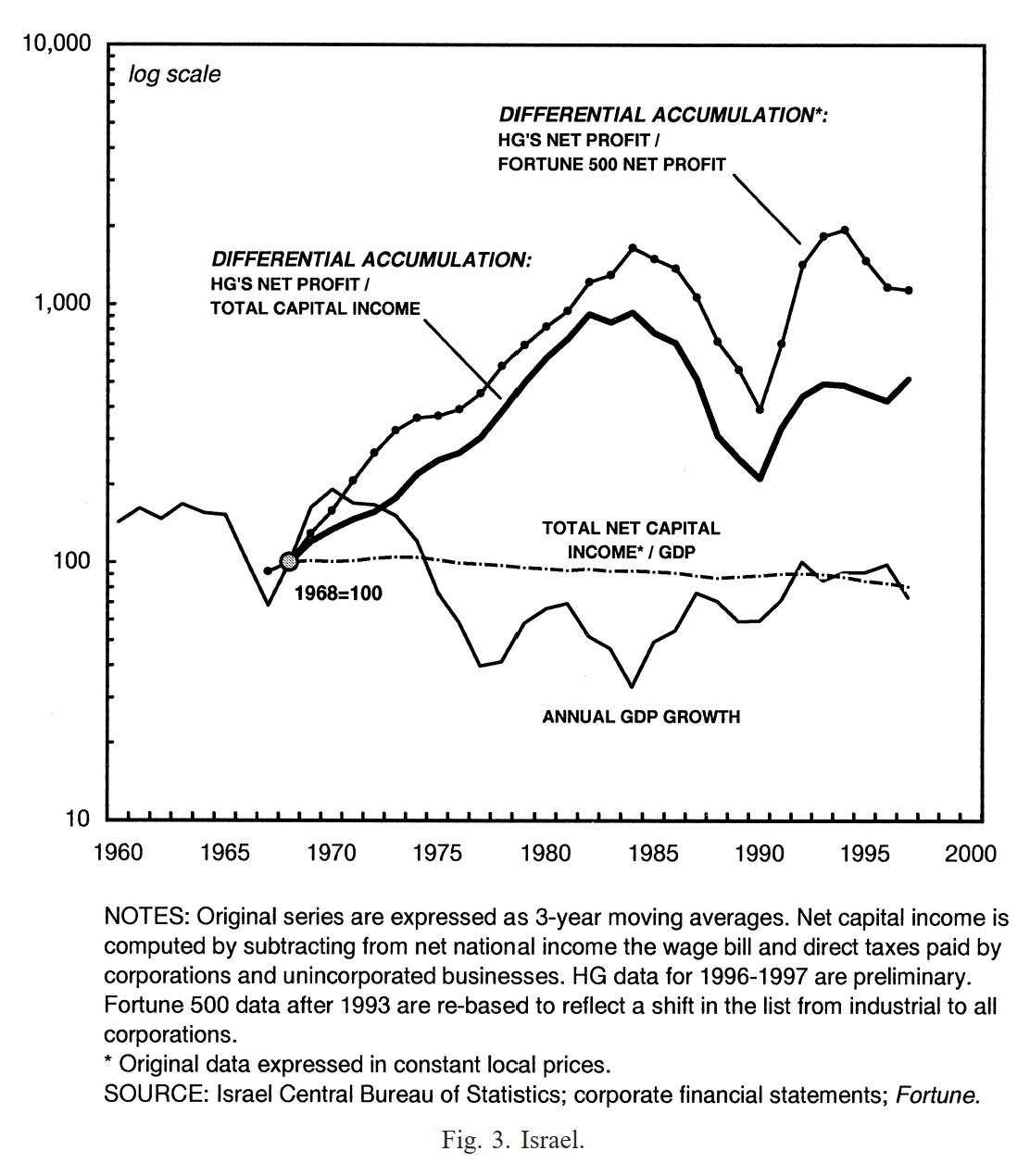

Below are a couple of graphs from a 2001 comparative article we wrote on the dominant capital groups in South Africa and Israel and the extent to which their differential accumulation impacted the end of Apartheid and the agreement with the Palestinians. In this article, we tried to look at both global and local measures, and we often did so in the same graph.

Going Global: Differential Accumulation and the Great U-turn in South Africa and Israel

- This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Some memorable war novels, many of them autobiographical, are listed below. They are all worth reading.

1. Babchenko, Arkadiæi. 2008. One Soldier’s War in Chechnya. Translated from the Russian by Nick Allen. London: Portobello.

2. Ballard, J. G. 1984. Empire of the Sun. A Novel. New York: Simon and Schuster.

3. Browning, Christopher R. 1998. Ordinary Men. Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Reissued with a New Afterward by the Author. 1st HarperPerennial ed. New York: HarperPerennial. [Not a novel, but a masterpiece nonetheless.]

4. Céline, Louis-Ferdinand. 1932. [1983]. Journey to the End of the Night. Translated by R. Manheim. np: New Directions. [The first part of the book on WWI is unmatched.]

5. Cendrars, Blaise. 1918. [1984]. The Severed Hand. New York: Stein & Day Pub.

6. Clavell, James. 1962. King Rat. 1st ed. Boston: Little Brown.

7. Coonts, Stephen. 1986. Flight of the Intruder. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press.

8. Deighton, Len. 1982. Goodbye, Mickey Mouse. 1st ed. New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House.

9. Duffy, Peter. 2003. The Bielski Brothers. The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Saved 1,200 Jews, and Built a Village in the Forest. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins.

10. Fisher, David. 1983. The War Magician. New York: Coward-McCann.

11. Gary, Romain. 1960. A European Education. New York: Simon and Schuster.

12. Graves, Robert. 1929. Good-bye to All That. An Autobiography. London: Cape.

13. Hameiri, Avigdor. 1952. The Great Madness. New York: Vantage Press 1952.

14. Hasek, Jaroslav. 1937. The Good Soldier: Schweik. Translated by P. Selver. Garden City New York: The Sun Dial Press, Inc., Publishers.

15. Levi, Primo. 1960. If this is a Man. Translated from the Italian by Stuart Woolf. 2nd ed. London: Orion Press.

16. Malraux, André. 1934. Man’s Fate: La Condition Humaine. New York: Modern Library.

17. Marlantes, Karl. 2010. Matterhorn. A Novel of the Vietnam War. 1st ed. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press: Distributed by Publishers Group West.

18. MacLean, Alistair. 1955. H.M.S. Ulysses. London: Collins.

19. Monsarrat, Nicholas. 1951. The Cruel Sea. 1st ed. New York: Knopf.

20. Orwell, George. 1938. [1966]. Homage to Catalonia. (And Looking Back on the Spanish War). Harmondsworth, Middlessex, England: Penguin Books in association with Martin Segker & Warburg.

21. Remarque, Erich Maria. 1929. [1982]. All Quiet on the Western Front. New York: Ballantine Books.

22. Remarque, Erich Maria. 1954. A Time to Love and a Time to Die. Translated from the German by Denver Lindley. New York: Harcourt Brace.

23. Wouk, Herman. 1951. [2003]. The Caine Mutiny. A Novel of World War II. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Co.

24. Wouk, Herman. 1971. The Winds of War: A Novel. 1st ed. Boston: Little Brown.

25. Wouk, Herman. 1978. War and Remembrance: A Novel. 1st ed. Boston: Little Brown.

February 2, 2021 at 3:33 pm in reply to: Dominant Capital is Much More Powerful Than You Think #245264Thank you Blair for the interesting question.

In principle, the relevant universe is open-ended and depends on the question we seek to answer. In our work here, we compared the top corporations to all corporations. You suggest that the results might differ if we compare the top corporations to all firms — incorporated as well as unincorporated. The impact of this change can be assessed with additional research.

Some preliminary thoughts:

Your chart on ‘average firm size’ in the U.S. suggests that, compared to 1950, this size rose by about 80%. But your chart measures size in terms of the number of employees, whereas our paper here looks at size in terms of dollar amount of income — in this case, profit. And the temporal movement — and even the direction — of these two measures need not be the same.

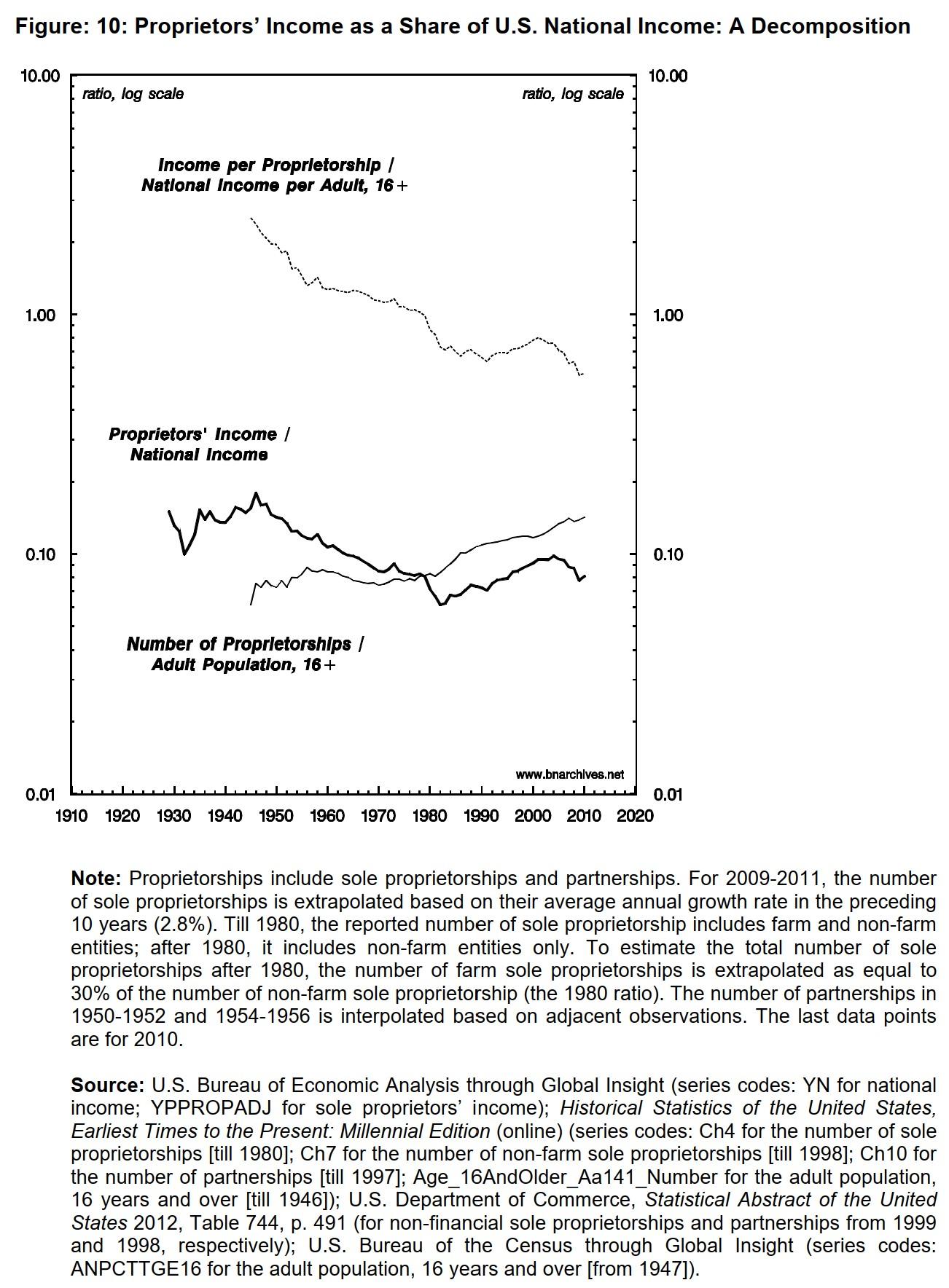

In our own 2012 paper ‘The Asymptotes of Power‘, we looked at proprietors’ income.

Figure 10 below shows that, while the number of proprietorships per adult has risen (solid thin line), overall proprietors’ income as a share of U.S. national income fell by more than 40% (thick line) and the ratio of income per proprietorship relative to national income per adult (dashed line) fell by about 75% (these percentages are all ballpark figures). So my initial impression is that the relative income size of proprietorships is falling even if their absolute employee size is rising.

Of course, the precise way in which these trends relate to the measures of our paper requires further empirical work.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Merridale, Catherine. 2006. Ivan’s War. Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945. 1st ed. New York: Metropolitan Books.

There is a huge literature on Soviet side of WWII. But this book is unique in its focus on the Soviet soldiers. Merridale, a British historian, conducted numerous interviews with war veterans and ordinary people who experienced the war first hand and weaved their recollections and thoughts with the broader history of the conflict. It reads like a story from another planet. Riveting and horrific.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

January 31, 2021 at 10:37 am in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245246The question is what do stock prices ‘represent’?

According to Keynes, in his General Theory, the answer is a differential guess about what others think they represent:

This tongue-in-cheek seems reasonable a description for short-term investment and for particular stocks, but over the longer term and for broad aggregates, investors price stocks by discounting risk-adjusted expected future earnings. In most cases, prices correlate positively with earnings expectations, and negatively with risk perceptions and the normal rate of return. The correlations themselves — particularly between prices and earnings — can change over time (see Figures 7 in our CasP Model of the Stock Market), but they tend to be positive.

From a capitalization perspective, terms such as ‘manias’, ‘bubbles’ and ‘irrational exuberance’ represent excessive profit expectations — or rising ‘hype’. Of course, most frenzied investors who buy into these upswings don’t think of future earnings. They follow Keynes’ narrative. But in their actions they drive up – and are further driven by — the hype.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

January 30, 2021 at 11:19 am in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245240Market tops are congested with hype-laden fanfare and scandals, which is where the ‘shoe shining boy’ theory of financial investment kicks in.

The theory, which many an exist-in-time mogul claim their own, posits that when you start getting investment tips from shoe-shiners and other folks who normally just work for a living, it’s time to sell your equity holdings.

January 29, 2021 at 4:21 pm in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245236Thank you Jeremy and Blair.

Capitalization is the ‘operational symbol’, to use Ulf Martin’s language, that creorders the capitalist mode of power. If this statement is correct, abolishing financial markets implies abolishing capitalism, or at least changing it so drastically that it becomes unrecognizable.

In the last section of our 2018 paper, ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’, titled ‘bridgehead’, we suggested one possible first step toward that end. It goes as follows:

[…]

Bridgehead

These considerations make praxis crucially dependent on fusing political action with ongoing empirical and theoretical research. To illustrate this necessity to know what we are doing, consider the following thought experiment. What if, instead of creordering the entire fabric of society, we start with a narrow bridgehead? Rather than trying to revolutionize the whole thing, we focus on one well-defined sphere. We inject into this sphere greater autonomy, cooperation and creativity, and then gradually tie these changes with, pull in and transform additional social spheres and processes, as well as our very understanding of society.

One promising site for such a bridgehead is the intersection of housing and pensions. The rapid urbanization of the planet makes affordable housing a key concern – and increasingly an impossible dream – for most wage earners. Similarly with pensions. According to the International Labour Organization, the vast majority of the world’s working-age population – up to 90 per cent – is not covered by pension schemes capable of providing adequate retirement income (Gillion et al. 2000). Left unattended, these trends are akin to social time-bombs. Used wisely, though, they might offer a leverage for autonomous social change around the world.

If we could come up with a democratically managed system that ploughs pension contributions into affordable housing and uses mortgage repayments and rent to pay pensioners, we might be able to align with and mobilize large chunks of society. And that’s just for starters. Affordable housing can be tied to sustainable urban planning, with creative architecture and new forms of public transportation to counteract and reverse the ecological devastation ushered in by uncontrollable sprawl. Those who live in autonomously developed urban areas and experience the democratic process might in turn wish to reform the educational system and broaden their self-government. The conceptual challenges created by a democratically managed pension-housing system might give rise to alternative accounting methods based on computations of public welfare rather than individual utility. Success in any of these areas could spill over into other areas of society, while failure would encourage rethinking and exploring of alternative routes. What started as a mere bridgehead could gradually expand into a broad creordering of society at large.

Can this thought experiment be translated into praxis? Perhaps – but only if we are able to conceive, develop and implement it in conjunction with ongoing empirical and theoretical research.

There are three related reasons for this requirement. One is that the changes outlined above constitute a direct assault on the capitalist mode of power: to democratize housing is to undermine the concentration of private real-estate ownership and management; to withdraw pension funds from the stock market is to arrest asset-price inflation and deprive capitalists of the nearly total leverage they have over middle-class incomes and the middle-class way of life; to demonstrate the efficacy of self-management in more and more realms of society is to delegitimize the sanctity of private enterprise and sound the death knell for accumulation.

So dominant capital and its power belt of government officials, economists and public-opinion makers are bound to fight this process nail and tooth. They will dismiss its underpinnings and attack its supporters. They will thwart its planning and sabotage its implementation. They will use sticks and carrots, brainwashing and threats, persuasion and violence. There is no way for us to withstand, resist and overcome these attacks without understanding – in general and in detail – the power logic they obey and the power structures they mobilize. And that understanding requires relentless, in-depth research.

Another reason is that even if we succeed and see our bridgehead gaining traction and spreading into other areas of society, initially these areas will have to coexist and interact with parallel structures of capitalist power. To put this parallelism in context, note that the modern capitalist principles of investment and accounting, discounting and finance and wage labour and increasing efficiency emerged in the early part of the second millennium AD, but that until very recently – perhaps as late as the nineteenth century – they operated within and alongside the logic of feudalism. And if that proves to be the case with post-capitalist alternatives, our praxis will depend crucially on understanding the ever-changing dynamics of capitalist power in which these alternatives exist.

Last but not least, enfolding research with praxis could boost the morale and optimism of progressive groups around the world. To show that democratic schemes such as pension-supported housing can actually work – i.e., that they serve the autonomy and wellbeing of their members while weakening the power logic of capital – is to demonstrate that we understand capitalism and can do better; that alternatives to capitalism can be imagined, planned and implemented.

This understanding, however, is difficult if not impossible to gain when we embrace academic dogma, cling to outdated political slogans and shun empirical research. The only way to achieve it – certainly on any meaningful scale – is through a series of autonomous, non-academic research institutes that are informed by and cater to societal action. These are not mere sidekicks. In our complex world, they have become a prerequisite for effective praxis.

On this subject, you might want to read:

Blair Fix, 2017, ‘Energy and Institution Size‘.

Bichler & Nitzan, 2020, ‘Growing Through Sabotage: Energizing Hierarchical Power‘.

***

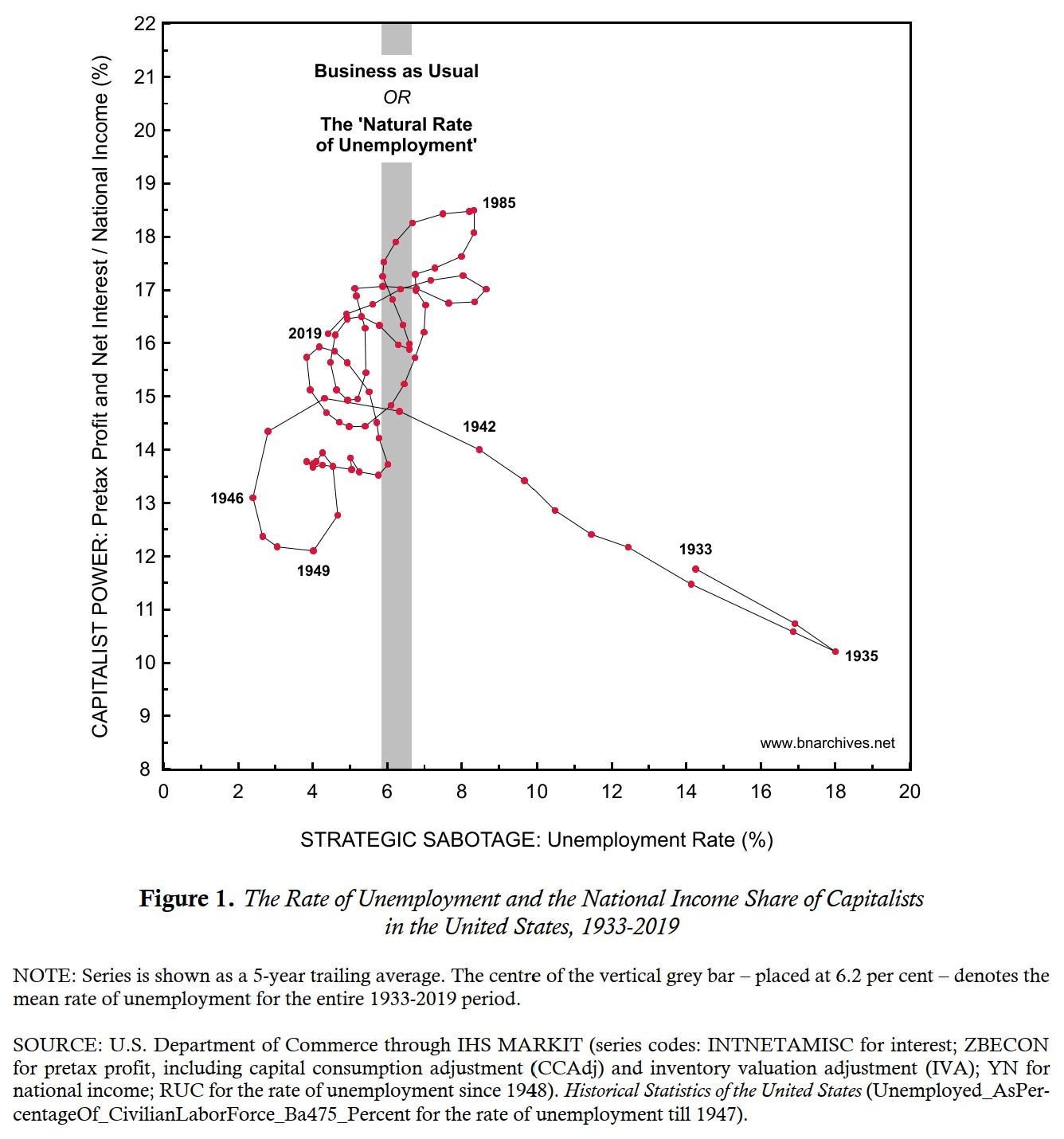

The chart below, taken from our recent paper ‘The Limits of Capitalized Power. A 2020 U.S. Update‘, suggests that U.S. capitalists require not absolute, but strategic sabotage: not too cold, not too warm.

Like with Goldilocks, too much sabotage reduces their earnings share, but so does too little sabotage. The optimal level of sabotage — otherwise known as ‘business as usual’ — is what economists call the ‘natural rate of unemployment’.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

How much difference do you think the ongoing economic reorganization toward already dominant, quarantine-readied businesses like Amazon, Walmart, etc. during the current health crisis will make for this regression trend?

It’s hard to tell. On the dominant capital side, some online firms have seen their EBIT rise significantly in 2020, but others have suffered. With smaller firms, if the carnage decimated mostly those at the very bottom of the distribution, the effect would be to increase the average EBIT. On balance, then, it’s hard to guess the direction differential EBIT took in 2019-2020.

[D]oes this annual rate of change graph look about the same if viewed with the top 50 firms rather than 200? What about the top 10?

Don’t know, we haven’t done the empirical work using different thresholds.

Is this tendency for the annual rate of change to regress the CasP version of Marx’s tendency for the rate of profit to fall?

Interesting question. Marx proposed that, over the long run, the organic composition of capital tends to rise faster than the rate of exploitation, and that this differential implied that, over the long run, the rate of profit will tend to fall. In our CasP case here, the downward tendency comes from the growing difficulty of keeping the pace of corporate amalgamation in particular and the growth of power in general.

The difference is threefold.

1. To demonstrate Marx’s tendency of the rate of profit to fall requires leaps of faith, particularly in defining the “proper” rate of profit. In CasP, the measurement of differential earnings and differential capitalization is relatively straightforward.

2. The reason for the downward tendencies is different. In Marx, it is inherent, in CasP it depends on the dynamics of power.

3. Marx’s claims have been researched for over a century. CasP work is in its infancy.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

December 30, 2020 at 11:37 am in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #245166There is plenty of research on institutionalized waste and inefficiency in capitalism, dating back to the early neo-Marxists and Veblen, among others.

Institutionalized waste and inefficiency are often seen as a ‘trick’ designed to create additional demand to ‘absorb’ the ever-growing surplus output generated by capitalism. They are presented as paradoxical, since the assumption (including of Veblen and the neo-Marxists) is that capitalists try to maximize profit, and that this maximization is generally presumed to require efficiency and abhor waste.

In CasP, the focus is not on maximum profit but differential profit, which often requires inefficiency and waste (and which can easily sustain both insofar as they are universal).

The tongue-in-cheek equation you refer to is written from the perspective of the individual manager (or rather the theorist of the individual manager), not the differential accumulators. And it seems nearly if not totally impossible to operationalize.

1. Do you know of any papers/books that analyse the crisis of 2007-08 through the lens of CasP?

Yes.

‘Systemic Fear, Modern Finance, and the Future of Capitalism’ (2010) http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/289/. This paper elicited a critique and reply here: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/314/ and eventually led to our ‘CasP Model of the Stock Market’ below.

‘The Asymptotes of Power’ (2012) http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/336/

‘Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Three Views on Economic Policy in Times of Crisis’ (2014) http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/414/

‘A CasP Model of the Stock Market’ (2016) http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/494/. Additional work on the subject by Hager and Baines: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/599/ and McMahon: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/643/

2. How would you go about assessing the power of organisations for which market cap data doesn’t exist

Unlisted assets, although having no observed market value, can be examined through estimates of sales, markups and profits. I’m not aware of CasP research on this subject.

3. [H]ow easy it is to do a CasP analysis when the powerful/controlling interest is a private entity (i.e. a private equity firm) who own a public company that is weak on paper with a low market cap?

When small assets are part of larger firms or conglomerates, they are hard to analyze independently – not only for CasP researchers, but for anyone. James McMahon grappled with this question in his 2015 PhD on the large entertainment conglomerates and their movie subsidiaries http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/463/.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by jmc.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

We just posted a new WPCASP, titled ‘The Limits of Capitalized Power: A 2020 Update’ http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/663/. The paper shows the significance of strategic sabotage for the distribution of income between capital and labour and between large and small firms. The purpose of strategic sabotage is to control production (among other things), so as to redistribute income and assets. If capitalists ‘liberated’ themselves from this process, how could they control it?

Reading suggestions:

- If you need the Full Monty, the place to start is our 2009 book: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/259/

- A shorter up-to-date summary is offered in this botched interview: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/640/

- A 2018 summary of CasP research — including the research of others — is given here: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/536/

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Labban asks: “Has capital accumulation been completely liberated from production? This seems to be the conclusion drawn from reading Nitzan and Bichler.”

Hmmm.

I have no idea where Labban concocts this claim from. It certainly doesn’t come from us, or from any CasP work I know of.

Our research reiterates, again and again, that capital is not about production, but about the control of production. But that doesn’t delink capital from production. Indeed, the very purpose of CasP research – our own as well as that of others — is to understand the ways in which capital creorders – or creates the order of – society, including its productive activity.

Now, given that capital is partly about the control of production, it is rather obvious – although not to Labban — that it cannot be ‘liberated’ from it.

But, then, maybe I misunderstand Labban’s misunderstanding….

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

You haven’t misinterpreted anything, Adam: qualitative research is as important as quantitative research, and facts always require theoretical interpretations — just as theory can rarely stand without empirical work.

-

AuthorReplies