Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Keynes considered the accumulation urge useful in bringing humanity to a state of material bliss, after which it would be recognized for what it was — a pathological condition befitting the psychiatrist couch. Had he though about it as the power drive that organized the capitalist world, he wouldn’t conclude it could be easily discarded.

Interesting proposal, Pieter.

If I understand you correctly, your aim is to create a taxonomy for mapping the processes of coordination, of which power relations are a subset.

Two comments come to mind.

1. Regardless of its specific details, such taxonomy is likely to face the built-in challenge of quantifying qualities – i.e., of bringing the incommensurate aspects of coordination into one or more common denominators without which quantification and aggregation are difficult if not impossible.

2. In some sense, your universal articulation, however tentative, puts the analytical cart before the empirical horses. I think it would be useful – for yourself and for others – to concertize the elements of your proposal with empirical examples and/or research, so as to assess both their logical validity and empirical fruitfulness. In my own experience, concrete examples often proved a useful check against going astray.

- This reply was modified 3 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

An empirical rather than analytical observation, right?

I think a bit of both.

1. Replacement cost is based on prices of newly produced capital goods. Unlike the prices of existing capital goods, which reflect the changing capitalization of their risk-adjusted expected earnings, among other factors, those of new capital goods are commonly ‘administered’ by their producers in line with normal cost and desired markup. During times of inflation and high interest rates, these administered prices tend to rise.

2. Market capitalization is affected by inflation positively (mainly by boosting expected profit in the numerator), as well as negatively (by increasing the discount rate in the denominator). However, the capitalization formula suggests that the latter (-ve) impact will usually outweigh the former (+ve) impact. For example, all else remaining the same, a 5% increase in expected future profit due to 5% increase in prices, accompanied by a 5 percentage points increase in the discount rate from 3% to 8%, will reduce capitalization by roughly 60%.

Obviously, these are partial back-of-the envelope arguments that invite further research….

Thank you for the thoughtful comments, Max. Here are three observations.

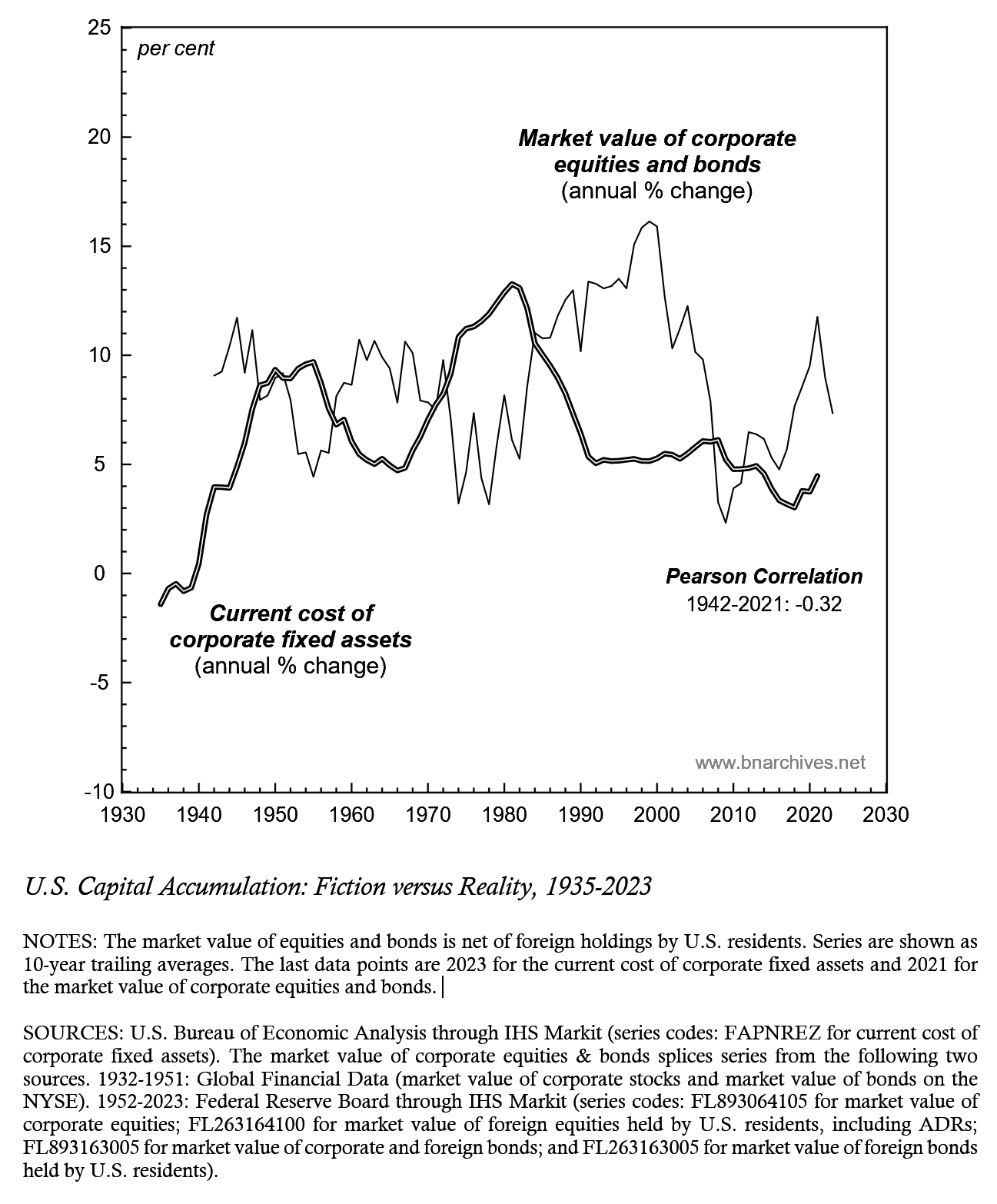

1. Our figure uses replacement cost because, in principle, this is what national-account statisticians use to impute the ‘real capital stock’ (= replacement cost / price index of investment goods). In other words, when economic researchers – be they NC or heterodox – use the ‘real capital stock’, they use not its utils or SNALT content, but the capitalized price of ‘capital goods’, corrected, or so they believe, for price changes. And since this ‘real’ measurement template applies not only to capital goods, but to all commodities, it follows that value theories are not only conceptually circular/arbitrary but also lack an objective measure to quantify the ‘real economy’ they theorize.

2. Why does the replacement cost of the capital stock oscillate inversely with corporate capitalization? Although we haven’t researched this question, one possible answer is the co-movement of inflation and interest rates, which tends to have a positive effect on the replacement cost of the capital stock and a negative impact on corporate capitalization.

3. You suggest that established heterodox political economists are busy analyzing the ‘distortions’ of finance and other extra-economic ills and are unaware of or indifferent to the fact that they do not have a consistent theory of value to stand on. I agree – but, based on our long experience, I don’t think this is a trap we can easily trick or lure them out of. We are likely to be better received by younger thinkers — though even here, the window of opportunity tends to close rather quickly.

“…the real capital stock, which political economists see as the beginning and end of capitalism, has nothing to do with (tangible) book value, which is the sole god of heterodox, anti-finance, economists.”

While this statement may be theoretically correct, it is NOT what we want to say.

Our point, rather, is that forward-looking capitalization and backward-looking real capital are de-linked (and in the U.S. case inversely correlated, as the figure below shows).

I think that Hudson’s reference to ‘book value’ here is misleading; as I indicated above, book value represents forward-looking capitalization at the point of its recording and therefore includes rent which Hudson wishes to exclude…. From his vantage point, it would be more accurate to talk of ‘real capital’, and specifically, of the direct + indirect ‘labour cost’ of producing it.

I think that Hudson’s reference to ‘book value’ here is misleading; as I indicated above, book value represents forward-looking capitalization at the point of its recording and therefore includes rent which Hudson wishes to exclude…. From his vantage point, it would be more accurate to talk of ‘real capital’, and specifically, of the direct + indirect ‘labour cost’ of producing it.- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

March 12, 2025 at 10:33 am in reply to: Capital as Power in the 21st Century: A Conversation #250239If I understand you correctly, your question concerns the difference between ‘real capital’ and ‘book value’.

REAL CAPITAL is an economic concept, denominated in universal units of either neoclassical utils or Marxist SNALT (socially necessary abstract labour time). The utils/SNALT presumably contained in any real capital were generated/produced in the past. Economists claim they can measure real capital, but as we explain in Chapter 8 of Capital as Power (2009), their measurement is entirely arbitrary if not circular.

BOOK VALUE is an accounting concept, denominated in dollars and cents. Usually, it denotes the money price of the asset at the time of its purchase. In Capital as Power (pp. 255-256) we note that book value represents the asset’s forward-looking capitalization at the time of its acquisition (the oil-tanker example). This feature means that, unlike the fluctuating market capitalization on the stock and bond markets, once set, book value no longer changes.

Are these two concepts related? Perhaps — but only in a perfectly competitive equilibrium with a perfectly known future (+ other assumptions that eliminate all resemblance to any known society).

- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Responding with fundamental critiques of neoclassical or Marxist value theories is not really effective in this context. So a reorientation of exposition and argument might be required if we to facilitate more fruitful engagements.

So far, our exposition — namely, a critique of existing neoclassical and Marxist frameworks and findings + an articulation of CasP’s own framework and research — seems to have resonated with young, free-spirited researchers (like yourself) and to have elicited more or less dead silence from established political economists.

So something in our exposition (and substance) speaks to one group while deterring another, and I wonder how you and others think this exposition can be ‘reoriented’ to make engagements more fruitful without diluting CasP’s contents.

- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

I look forward to your take on the conversation and the hurdles for CasP it points to.

Thank you for the question. Could you please elaborate?

October 17, 2024 at 8:01 pm in reply to: The dark matter of CasP? What can’t we observe about capitalist power? #250159The ‘dark-matter’ syndrome is inherent to scientific modelling. All scientific models are wrong to some extent – either because the modellers exclude important elements and misrepresent or omit relevant relations, or because they over-simplify. The built-in errors are not always apparent — for example, initially, Ptolemaic cosmology seemed superior to the heliocentric one. And often the errors are being hidden by inventing new terms, such as Phlogiston in chemistry, the production-function ‘residual’ in economics, and (perhaps) the ‘dark matter’ of cosmology.

I think that, as a new approach with few researches and a very limited number of studies, CasP must be full of dark matter, residuals and Phlogiston-like substances. And I suspect that its unknowns extend far beyond the black and grey economies and unreported activities. In the grander scheme of things, CasP theory is still in its early sketching stages, and even its most brilliant studies merely scratch the empirical surface.

But there is an upside. Unlike neoclassical theory, which gave up science in defence of capitalism, and contrary to Marxism, which has been impaired by dogma and/or surrendered to postism, CasP is still young and uncommitted and therefore able to plow through many of these difficulties — at least for the time being!

- This reply was modified 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

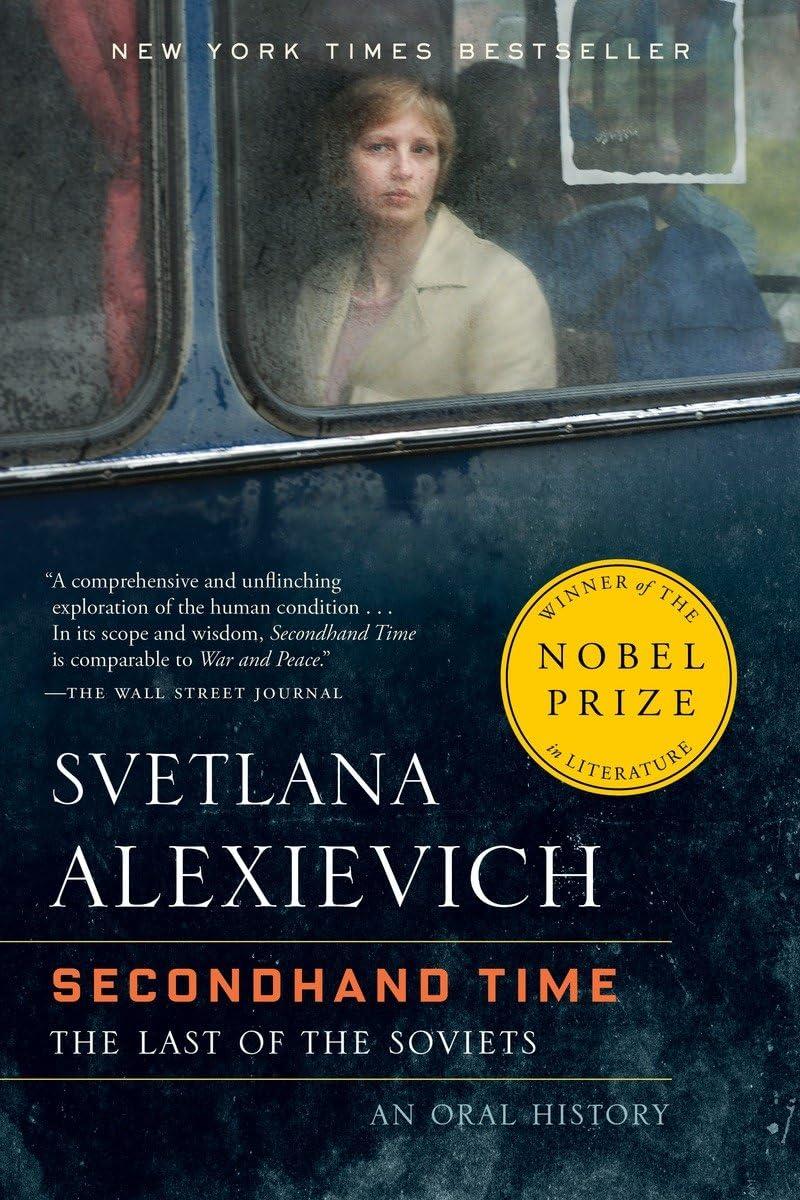

Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time chronicles the transition from the Soviet mode of power to Russia’s new capitalist mode of power. And it is unique because it is written not from the top, but from the bottom. The book is a collection of interviews conducted over a period of more than twenty years following the fall of communism. Alexievich spoke with many people from all walks of life, old and young, communist and anti-communist, those who lived in the Soviet Union and others born after its collapse. None of them belonged to the elite. They were all from the underlying population.

The stories are riveting, sometime mind-bending and often horrific. They are also very diverse and therefore difficult to generalize, certainly not after the first read.

But one lesson seems clear: hierarchical modes power, be they communist, capitalist or something else, are incredibly powerful. Stalin’s regime, like its tsarist predecessors, managed to butcher, enslave, terrorize and condition Russians in the millions. And the capitalist oligarchs and their current czar, Putin, use new social technologies to achieve similar ends.

Faced with these mega-machines, the path toward direct democracy is daunting indeed.

- This reply was modified 9 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 9 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

I agree with your hesitancy, James. However.

I think Whitehead did a very good job describing the mental state on which U.S. slavery was built.

I thought that the most unsettling parts of the book were those describing the honorific cruelty against captured runaway slaves, cruelly that often served as lunchtime entertainment for the puritan masters and a stern warning to their remaining slaves.

This cruelty was made possible by seeing slaves as ‘non-persons’. Even where salves were liberated, like in North Carolina, they were often turned into state property, and, as such, were fair game for biological experimentation.

Slave hunters continued to operate in ‘free states’, where slavery was prohibited, on the premise that the sanctity of property trumped over the sanctity of life. These hunters acted like ‘private’ IRS or FBI agents, with trans-border privileges, to find and return runaways to their ‘legal owners’.

Finally, and perhaps most devastatingly, the slaves themselves often lacked the most basic sense of self. Families disintegrated, children were sold, parents were murdered. There was no ‘community’, let alone a stable one, so there was no social locus to relate to and construct one’s own social personality.

- This reply was modified 9 months, 3 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 9 months, 3 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 9 months, 3 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Blood and Oil in the Orient: A 2024 Update

After years of falling relative oil prices and differential oil losses, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine boosted both and helped pull the Middle East out of its ‘danger zone’.

A year later, the war that broke out between Israel on the one hand, and Hamas-Islamic Jihad-Hezbollah-Iran on the other, promised to increase those relative prices and differential returns even further.

But these hopes were dashed.

As the figure below shows, in 2023, relative prices and differential profits both sank, pushing the Middle East once again into the ‘danger zone’.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 1 week ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Jiang, Rong. 2008. Wolf Totem. Translated by Howard Goldblatt. New York: Penguin Press.

A semi-autobiographical novel about a Chinese student sent during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s to live as a herder in Inner Mongolia.

The broader context is the impact of population growth on the changing balance between agricultural and nomadic life and the inevitable destruction of the latter by the former.

The focus is the radically different worldviews of the two groups — the complex, long-term holistic perception of the nomads versus the one-dimensional, short-term emphasis on the farmers.

The main axis are the wolves: their pivotal role in regulating the ecology of the steppe, their impact on the consciousness and behaviour of both humans and animals, and their lasting imprint on the historical development of Mongolia and beyond.

Thrilling.

- This reply was modified 1 year, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 1 year, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

True — but (1) a significant part of this increase is due to input-price inflation, and (2) construction is roughly 4% of U.S. GDP, so its impact on the overall growth trend is limited.

-

AuthorReplies