Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

From my brief glance I’m sort of surprised CASP doesnt appeared to have been reviewed much by some people in the field

For more on the relationship of mainstream and Marxist political economists to CasP, see “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/641/, written to contextualize the rejection of our invited interview with Revue de la régulation: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/640/.

I think what i consider the best ‘neo/classicals’ –the ones who did the theory—Arrow, Hahn, Samuelson, Mantel, Debreu, Sonnenschein..–i dont think either misunderstood or misrepresented the world anymore than anyone else before or after. I think they were quite clear that they were making an ideal model which did not apply to the real world . They just understood their model and made no claims about the real world.

Many neoclassical economists hide behind this Teflon veil: it’s ‘just math’.

The high and low priests who engage in this type of ‘just math’ call themselves economists, not ‘mathematicians’. And I think it is wrong to say that they do not intend their models to apply to the real world. They don’t speak about abstract X, Y and Z entities, but about social concepts such as rational agents, markets, utility maximization, productivity, growth, income, etc (as well as the ‘distortion’ that upset these pristine social concepts). They also tend to be highly biased in favour of capitalist ideology, both in terms of the questions they ask and the answers they give. Last but not least, they never turn down a Nobel Economics prize, least of all on the grounds that they are ‘not economists’ and that their theories are not about the ‘economy’.

So when economists assume ‘perfect information’, I think they are convinced that this concept represents how the world works or at least should work, and that it should be the basis on which economists could, at some point, be able to understand it. In doing so, they mislead themselves and their followers to never look at many of the things that actually mater in capitalists society. In my view, this is the main reason why they are heavily supported and often exclusively subsidized by corporations and governments.

I doubt that any of this can be said about theoretical physics, at least not in this harsh way.

For more on these issues, see our “Capital Accumulation: Fiction and Reality” http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/456/

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Would profit exist in a world characterized by perfect, symmetrical information?

Let’s assume that: (1) profit is a manifestation of power; (2) power depends on the use/threat of (i) physical force and (ii) mental/emotional control; and (3) perfect, symmetrical information removes (ii). With these assumptions, profits will depend only on the use/threat of physical force and therefore will be greatly reduced.

However, a world of perfect, symmetrical information is a logical impossibility.

It is impossible because (1) if there is even a whiff of free-will, the future is unknowable; (2) “knowledge”, even of the past, depends, often greatly, on open-ended interpretation; (3) human beings do not have access to all facts, theories and interpretations — and even if they had such access, they don’t know how to tease “perfect” information out of it; (4), and crucially, even if in principle some human beings can have access to all facts, theories and interpretations, and even if they can objectively combine them, in practice, they can always block others from accessing such information, perfect or otherwise….

This is why neoclassicists assume perfect information: it enables them to misunderstand and misrepresent the world, perfectly.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

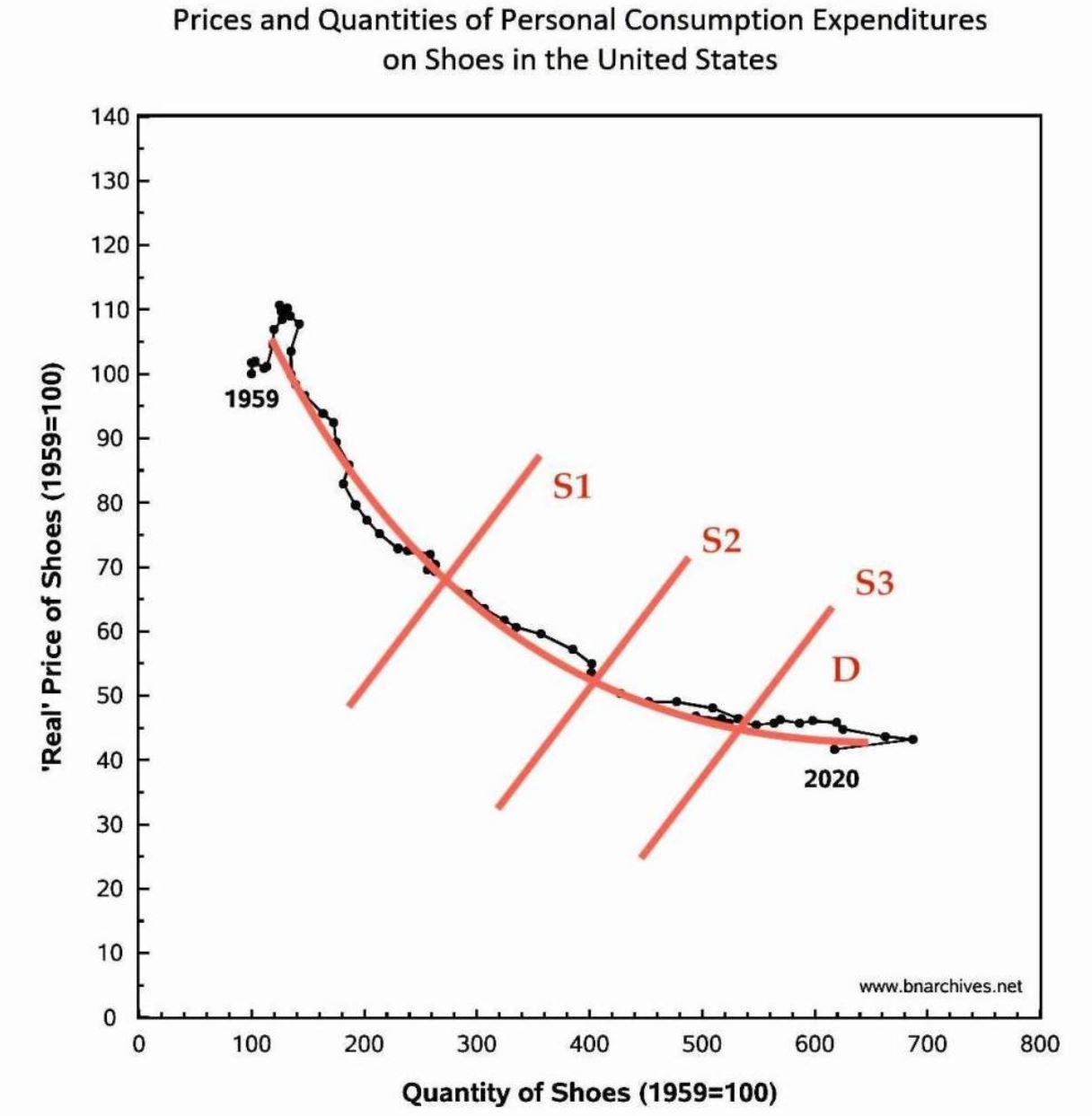

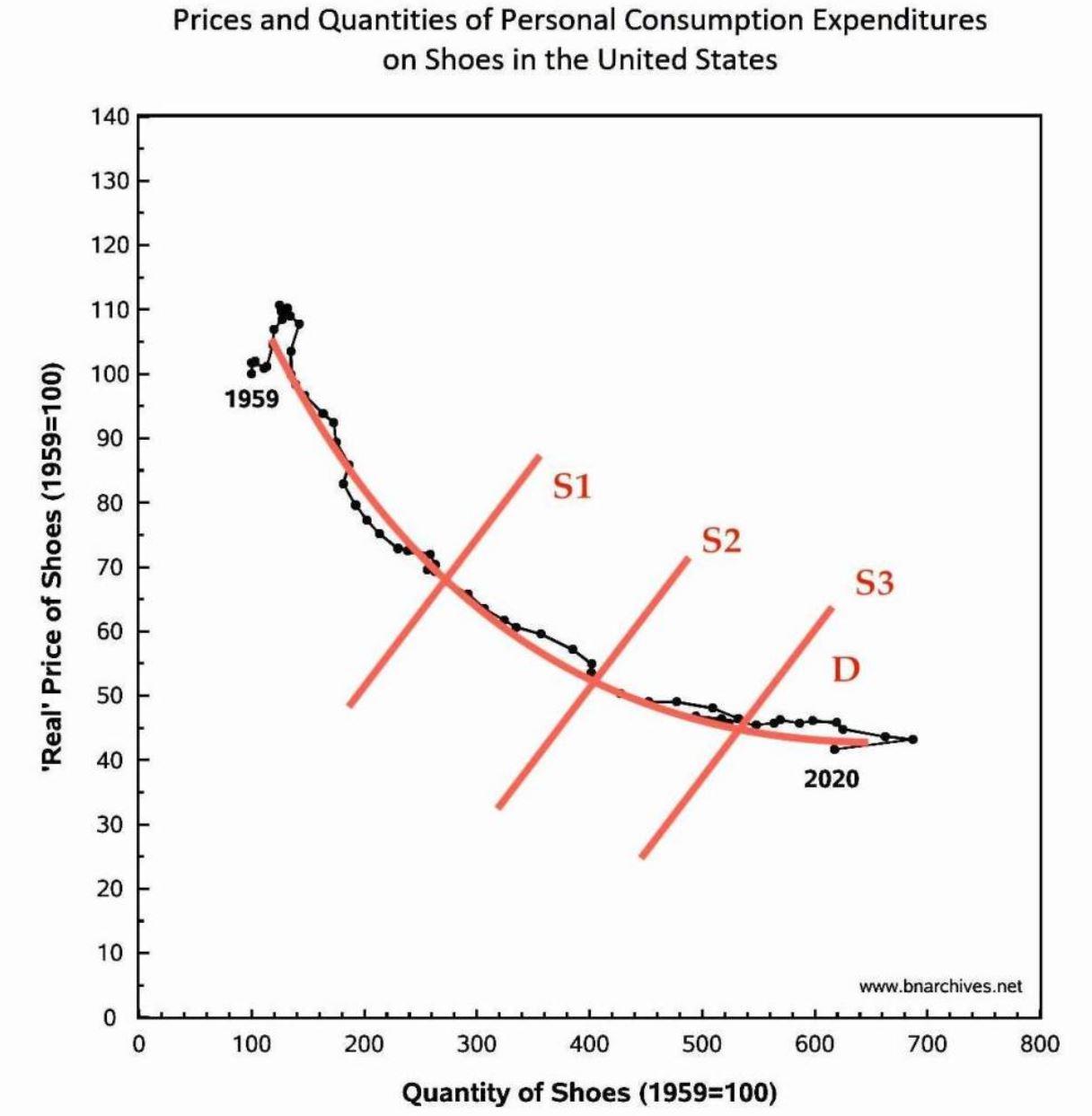

In my classes, both undergraduate and graduate, I present students with this empirical chart and ask them whether the time series in it represents supply, demand, both, or neither. Many students, like Professor Douglas, think that because the curve slopes downward it must be the demand curve, not realizing that their answer implies that none of the underlying parameters changed (or that they changed in a way that their different impacts exactly offset each other). They also don’t realize that whatever their answer, it can never be verified.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

This is a reply to our Working Paper by Alexander Douglas.

It is taken from his blog here: https://axdouglas.com/2021/03/17/defending-microeconomics/ and can also be found here: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/679/

***

Defending Microeconomics?!

by Alexander X. Douglas

I was sent a link to this article by a colleague, who was concerned with the boldness of the central claim – that standard economic theory explains nothing about market behaviour. I thought I might as well share the outline of my response here.

I’m far from being a defender of the foundations of mainstream microeconomics. But this attack goes much too quickly, in my view. I find myself in the odd position of defending something I don’t believe in from an attack I think is unfair – indeed counterproductive.

Bichler and Nitzan attack the textbook explanation of prices and quantities as determined by an equilibrium between supply and demand.

Textbook economics represents market equilibrium, for a given commodity, as the intersection between a supply curve and a demand curve. Bichler and Nitzan notice that we never observe demand or supply curves. Of course not, because these represent counterfactuals: the maximum amount consumers would buy if the price were higher/lower, the minimum price firms would charge if the quantity purchased were higher/lower. The famous ‘scissors’ diagram in all the textbooks is not a picture of different states that a system could be in at different times; it’s a picture of a single moment in time, along with a bunch of counterfactuals for that same moment. As Joan Robinson said, time is at right angles to the diagram. So yes, of course supply and demand curves can’t be observed. We don’t observe counterfactuals; we only observe factuals, if I can say that. That is, we only see the price and quantity determined by the actual (factual?) market. So far what Bichler and Nitzan say is obviously true. How do they get from an obvious truth to a devastating critique?

First, they look at a time-series of actual market data. Each point represents the quantity of shoes purchased in a given year (in the US) and the average price paid for a pair of shoes in that year:

They then point out that this data is consistent with each point being a market equilibrium between a different supply and demand curve:

But it’s also consistent with each point being off the equilibrium in any number of ways:

What does this prove? Not much, in my view. It’s hardly news that supply and demand curves can be drawn so as to intersect at any point you like. Since they can’t be observed, they must be constructed on the basis of assumptions. Bichler and Nitzan draw their curves arbitrarily, but they propose that neoclassical economists do the same:

But how did we know what these curves looked like and that they indeed equilibrated at those designated points?

The answer is we didn’t. Just like the neoclassicists, we have no idea what actual demand and supply curves look like. Just like the neoclassicists, we simply plotted them so that they intersected in the observations for 1995, 2000 and 2010. And like the neoclassicists, we did so because these intersections are consistent with the neoclassical doctrine.

But the “just like the neoclassicists” clauses here don’t seem right to me. The ‘neoclassicists’ would surely require some rationale for drawing supply and demand curves a certain way. The curves are counterfactual and unobservable, but they’re meant to represent plausible counterfactuals – plausible given certain assumptions. You can’t just draw them anywhere you like; you need a story about why you draw them where you do.

Now the shifting supply curves drawn by Bichler and Nitzan – S1, S2, S3 – make sense on standard neoclassical assumptions. The years seem roughly to move from left to right in this time-series. A standard assumption is that technology improves over time, and better technology means more efficient, lower-cost production. So this will constantly push the supply curve outwards.

But the shifting demand curves drawn by Bichler and Nitzan – D1, D2, D3 – seem entirely unmotivated. Of course demand changes. Tastes change; changes in income affect demand; changes in one market act unpredictably upon the conditions of all other markets; policy changes have their effects, etc. etc. But I can’t think of any reason the ‘neoclassicists’ would have for supposing a constant outward shift of the demand curve over time. On the contrary, I think the ‘textbook’ assumption would have stable demand – a single demand curve intersected by the outward-shifting supply curves. The curve might jump around a bit, but the jumps could be assumed to go in random directions and thus cancel out over a long period. Then you’d get this:

And this seems to show at least a part of the textbook theory being confirmed in the data. A crucial part of the standard theory is that demand curves slope downwards: as price falls, consumers want to purchase more. Of course here there’s some curve-fitting to make the demand curve match the data. But its basic shape can also be supported on ‘plausible’ assumptions: as markets get saturated, the demand elasticity decreases – thus the flattening out of the curve towards the east.

The above plotting of supply and demand curves isn’t purely arbitrary; it’s based on standard assumptions. So with those (textbook) assumption in place, we have a confirmation of the textbook theory. Nor are the curves simply plotted to match the data, as Bichler and Nitzan’s are; they are justifiable on standard assumptions.

It’s odd to me that Bichler and Nitzan present this data against the mainstream case. I must admit that the part of me that wants textbook microeconomics to fail was disappointed by how well this time-series actually bears out the textbook story. I was actually surprised to see that people really do seem, like the consumers in the textbooks, to buy more shoes as technology reduces the price.

Bichler and Nitzan also cite data showing that the elasticity of demand for different goods varies widely:

This is another case where, aiming to undermine the textbook story, they manage to find data that confirms it! If we were judging the empirical confirmation of a specific economic model we could look at things like the demand elasticity it assumes and see whether this is confirmed in the data. But Bichler and Nitzan are judging textbook microeconomic theory in general. That theory says nothing at all about the specific slope or shape of demand curves. It states only that they slope downwards, and that is, apparently, confirmed in the data.Standard economic theory makes only very generic predictions – more specific ones need specific models. An example of a generic prediction is what appears to be confirmed in Bichler and Nitzan’s Figure 2: as the price falls, people buy more. Of course the data doesn’t confirm that prediction on its own. You need to assume a stable, downward-sloping demand curve. But Bichler and Nitzan inadvertently find empirical support for that also: they have a table that seems to show that, whatever shape the demand curve might have, it’s generally a downward-sloping one.

To repeat, my reservations about their critique don’t stem from a strong faith in the explanatory power of standard microeconomics. My worry is that the material their critique presents seems to be precisely the sort of thing a textbook might include as a defence of the theory. As a critique of textbook microeconomics, this might be a step backwards.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

March 1, 2021 at 10:04 pm in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245396Hi Jeremy:

1.

The percentage of pension ‘coverage’ per se does not tell us the $ size of pension assets saved by different groups.

Here is a table from the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finance, showing the size of retirement accounts by percentile of net worth:

The table suggests that, in 2019, the bottom half of the population has very small retirement account saving: the poorest 25% of households have $4,700 per family, and the next 25% have $19,000 per family. The next 25% have more, but scarcely enough to retire. These savings have risen only marginally over the past 20 years.

2.

Regarding the use of higher returns to lure the underlying population away from the stock market. The vast majority of those who would join such a project are not “invested” in the stock market, certainly not in a meaningful way (you can verify it by looking at the tables offered by the Survey of Consumer Finance). And the attractiveness of the bridgehead program, I think, is not its differential rate of return, but the housing and retirement security it offers and the participation in shaping one’s own life.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 20, 2021 at 1:00 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245384Yes, we often project our social order onto the natural world. But we shouldn’t take this as far as the post modernists, and conclude that we can never understand the natural world because everything is clouded by ideology. Despite our tendency to delude ourselves, good science does happen.

At a risk of sounding simplistic, I’d say that human thinking requires categories; categories imply ‘likeness’; and metaphors are a major form of likeness: they compare and in some sense unite previously orthogonal domains.

Metaphors are everywhere in human thinking, and they pervade both organized religion and science.

One key difference between organized religion and science, is that organized religion worships its own inventions as if they are hetronomously given, while science is painfully aware that its frameworks and theories are its own Protagorean making.

In the monotheistic religions, God is literally the king of the universe, has to be obeyed by its inventors and their laity via his self-nominated earthy representatives, and remains in his position for millennia (or until the worshippers perish). In science, theories and even worldviews, no matter how entrenched, can succumb to counter evidence in a historical jiffy.

I think that as long as we remember that our metaphors are own inventions and don’t use them as externally given evidence, we remain scientists. When we start sanctifying our metaphors as heteronomous, we move over to the domain of organized religion.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 19, 2021 at 5:58 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245381Blair, I saw your post only after posting mine, so just a small comment.

What Sober and Wilson describe is hardly ironic. It is a well-known pattern throughout history. You yourself use the term ‘competition’, but is there really competition in nature, or are we simply imposing our own concept on it? Could Darwin’s ‘natural selection’ appear before the ‘competitive’ world from which Malthus’ theory of population emerged?

February 19, 2021 at 5:35 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245378Thank you for the detailed answer, David. This is all very interesting and inseminating. I remember thirty odd years ago reading and being fascinated by Peter Russell’s work on the ‘global brain’, and I suspect that with easy computing and instant communication this line of argumentation has since exploded.

But it seems to me that the issues I have raised earlier still linger. Your descriptions of the living body and of the planetary body continue to rely heavily on the way in which we describe our society. In your 650-word post above you have used the terms ‘competition’, ‘conflict’, ‘greed’, ‘violence’, ‘reward’, ‘homicide’, ‘suicide’, ‘survival’ and ‘cannibalism’, and I think many more social terms would have crept up were we to continue.

My point: we are imposing our own social world on the natural universe around us. And we aren’t the first to do so. Human societies have always conceived the cosmos in this way. But if the natural world is a human-made mirror of our own, using it as a model is a complicating detour (hat tip to Paul Samuelson). Why not simply look at ourselves?

Regarding apoptosis, a neat video by my daughter, Elvire: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vmtK-bAC5

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 19, 2021 at 12:03 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245372David,

1. There is no need to swear allegiance to CasP. We are doing open science, with critique as its bloodline (in honour of biology!). And your notes are all thought provoking.

2. Alternative formulations are welcome (if they weren’t, there would be no CasP theory…)

3. My main beef with biological body metaphors is that they are not very good in describing internal power struggles, let alone inherent and conscious ones.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but biologists tend to think of bodies as resonating systems whose purpose is ‘survival’ and whose ‘diseases’ are either externally inflicted or the consequence of malfunction. Human societies are different. On some level, they appear resonating. People go to work every day, they think more or less alike, they fight external enemies, they police against internal crime, etc. But much of this apparent resonance is the consequence of an ongoing struggle, often conscious, between a ruling class that seeks and generally succeeds in imposing its own order and the ruled who resist this order.

Can this ongoing internal conflict be effectively described with body metaphors? Is the brain in ‘conflict’ with other organs? Do the heart and kidneys ever try to ‘take over’ the brain in order to rule the body in its stead? Are some cells knowingly ‘fighting’ or ‘forced into submission by’ other cells?

4. And speaking about metaphors:

I believe the emergence of hierarchically organized power societies is better modeled by the emergence of early nervous systems in nature: when cells first specialized to be able to respond to changes in their local and distant environments via depolarization of the cell membrane (action potential), and began organizing into functional hierarchies and major functional systems to facilitate ever greater economies of information transfer, retention, and organization.

Notice how your biology relies on social metaphors. The terms ‘hierarchies’, ‘economies’ and ‘information’ are all borrowed from our understanding of society…

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 17, 2021 at 3:26 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245367Thank you David for another very interesting note.

I must admit I’m no longer sure about the point of contention. I think we all agree that humans are animate rather than inanimate, and that the laws of physics are insufficient to explain their actions and reactions. I think we further agree that there is no complete determinism in human affairs insofar as humans seem to have at least some ‘free will’ — or at least that is how it appears to us. Consequently, models of human and social interaction are open-ended.

But the models are not completely open-ended — first, because humans are conditioned by the laws of physics and chemistry as well as by their biology; and, second, because human psyche, beliefs and actions are at least partly shaped by their society. I think we probably agree on these claims as well.

With these tentative agreements in mind, the idea of a megamachine cannot be more than a loose metaphor. A society of humans cannot function like a clockwork or a Boston Dynamics army of robots. Even within the confines of physics, chemistry, biology and ideology there is plenty of room for novelty, and human beings have even started to change some of these very confines!

But when we consider society, power and resistance to power seem everyone. In this context, we might think of social power as the ability to creorder the evolution of society, and of resistance to power as attempts to oppose and prevent it. And one way of creordering society is to try and mechanize it — i.e., make it responsive, predictably, to one’s commands. This is the basic idea of the megamachine. A megamachine is always partial and never omnipotent for the reasons noted above, but its inherent incompleteness doesn’t prevent the ruling class from trying to impose it nonetheless.

Now, whether ‘mechanization’ in general and the ‘megamachine’ in particular are the most useful descriptions of this process is an open question. Looking at the world around us, I think they are. The mechanical, ‘rational’ worldview is still dominant, and it is accepted by modern rulers everywhere, perhaps more than ever. But I also agree that there could be other, equally useful or even better metaphors. And if you can think of such metaphors and show their robustness, please share your thoughts and findings!

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 16, 2021 at 4:37 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245360Complex societies are problem-solving organizations

The ‘problem solving’ engine takes a positive view: complexity is created because humans try to solve problems created by earlier complexity, attempts that in turn lead to more complexity, hence more problem solving, therefore more complexity, etc.

The negative view, which we much prefer, is described by Ulf Martin’s autocatalytic sprawl: social complexity is created when rulers impose their power, leading to resistance, which in turn leads to more imposition of power, more resistance, further imposition of power, etc. (see ‘Growing Through Sabotage’).

Both processes result in growing complexity, but for opposite reasons.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 15, 2021 at 8:36 pm in reply to: Questions Regarding Mumford’s Theory of the Mega-Machine #245344Thank you for the interesting note, David.

I think you present the metaphor of the megamachine too literally and perhaps too rigidly.

Shimshon and I understand the megamachine not as a one-to-one description of actual society, but as the way that the ruling class tries to structure society. The difference between the two views is important because the rulers are never totally successful in their impositions. And they are not totally successful because the very impositions of the megamachine create conflict and elicit resistance and struggle. This is the dialectical basis for Ulf Martin’s notion of the ‘autocatalytic sprawl’:

‘The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery’

Now, although the ruling class is never totally successful in its impositions, it is certainly successful to some extent. In this context, I think that your point that we cannot observe social cogs harming and killing other social cogs is not well-founded. Capitalism, for example, conditions people to see themselves as stand-alone ‘individuals’ and encourages them, quite effectively, to undercut and sabotage each other, presumably for their own ‘survival’. Capitalism also enables and often drives its subjects to kill other subjects — mostly indirectly, but also directly through organized crime and armed conflict.

Similarly, the fact that the rulers are locked into and conditioned by the logic of the megamachine — for example, the ritual of differential capitalization — doesn’t prevent them from taking plenty of initiative within that logic. And in a complex setting, these multiple initiatives generate multiple conflicts and lead to unpredictable developments. Also, the fact that the impositions of the megamachine are inherently incomplete is another important source of novelty.

can you think of any examples where this would be the case (i.e. where using log scale might be counterproductive)?

The answer depends on what you wish to show.

For example, suppose you have an exponentially growing series and you wish to show its variations regardless of magnitude, a log scale will be the right choice.

But if you are interested not in the variation, but in the actual level of the series — for example, when you plot the growth rate of GDP — a log scale will give you a skewed picture: it will stretch the low growth rates and squeeze the high ones. In this case, a linear scale will be better.

Adam,

The advantage of a vertical log scale are: (1) the slope of the time series is proportionate to the series’ temporal rate of change, so you can see how fast the series changes regardless of its absolute magnitude; this is not the case with a linear presentation; (2) it is equally easy to see small and large changes, which is a nice feature when the series grows or decays exponentially; this is not the case with a linear plot.

When these features are unnecessary or counterproductive, then a linear scale is better.

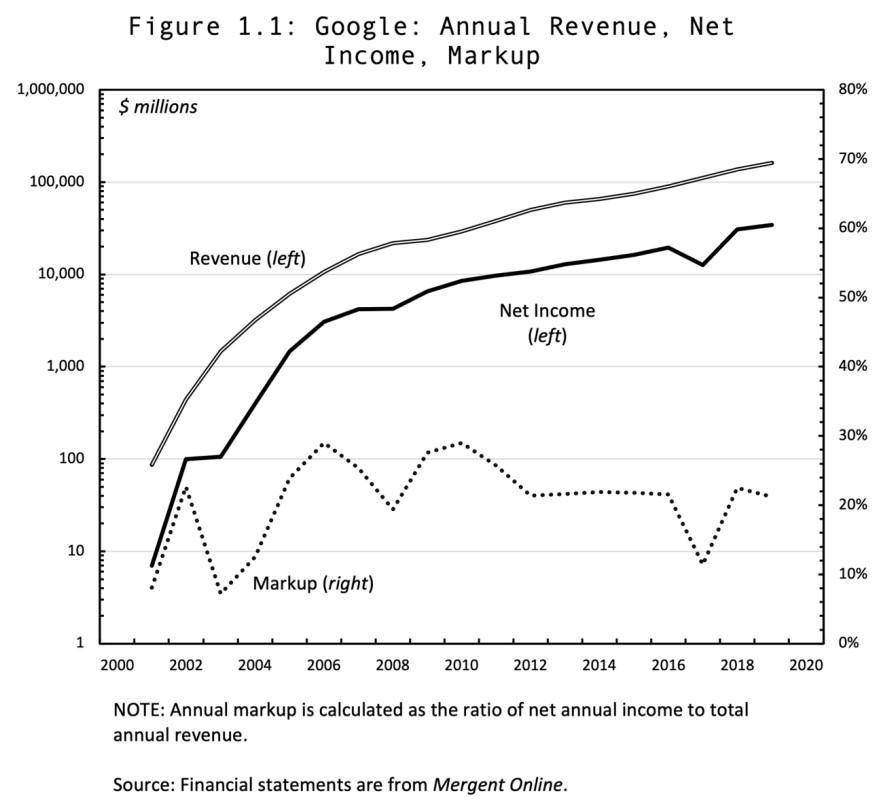

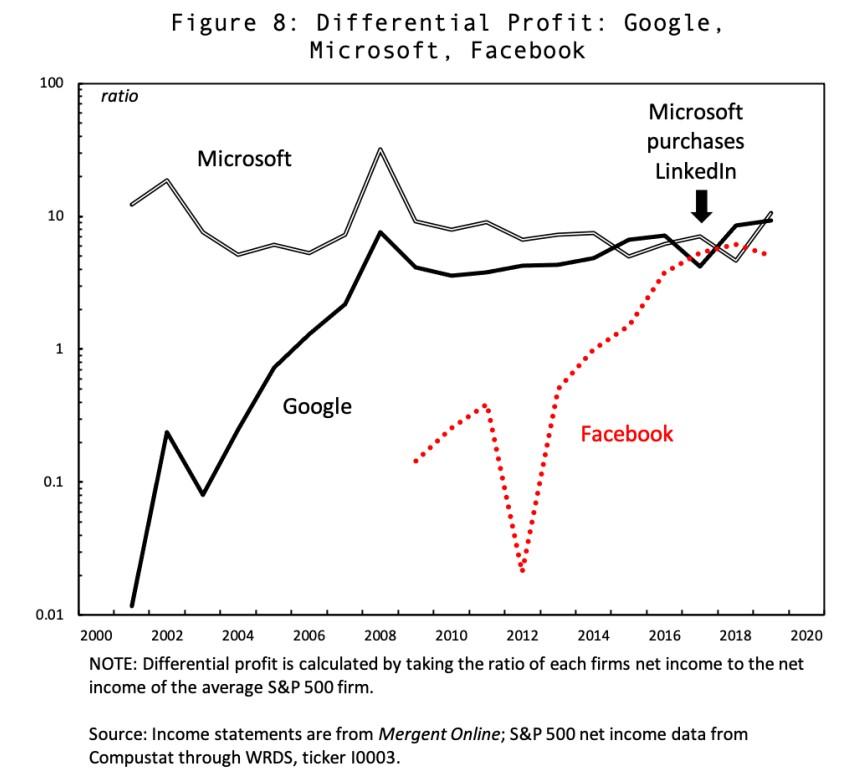

The following two charts, taken from Chris Moure’s 2021 Working Paper on Capital as Power, ‘Soft-wars‘, shows the usefulness of both log and linear scales.

The first figure shows the exponential growth of sales and profit on a log scale and the markup (ratio of profit to sale) on a linear scale.

The second chart compares the differential profit of three large firms that differ markedly in their levels and rates of change. A linear scale won’t be able to visually demonstrate these differences.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies