Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

December 10, 2021 at 2:15 pm in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247324

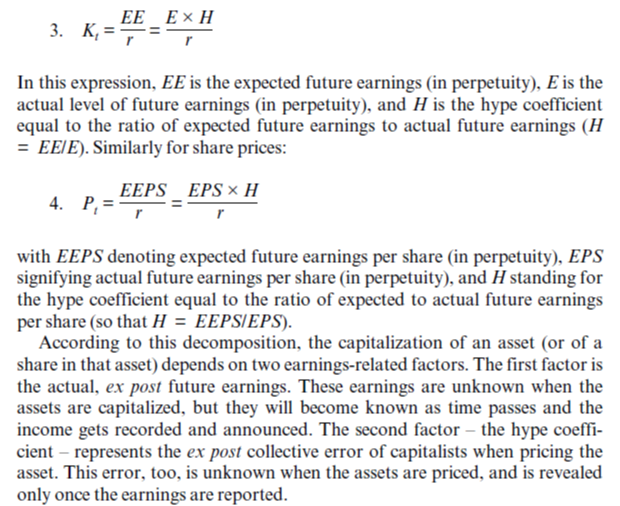

Some clarifications. Definition In our work, we defined: (1) hype = expected earnings / actual future earnings Hype has no moral connotations. You can call it ‘forecasting error’, ‘delusion’, ‘stupidity’, or ‘manipulations’. In retrospect, hype can be measured for any period — a day, two years (as we have done), a century, infinity. If you can specify expected earnings and measure actual earnings in retrospect, hype is their ratio. Scot is correct that, strictly speaking, hype is impossible to measure all the way to infinity. We cannot stand at the end of time and look back to see previous earnings. However, under normal circumstances, we can offer a good estimate of till-end-of-time earnings and therefore for till-end-of-time hype. The reason is that the discount factor makes more distant earnings less significant for capitalization, so usually 50 or 100 years, depending on the discount factor, will give you 80-90% or more of the capitalization of earnings all the way to infinity. And 100 years of earnings is certainly something we can examine in retrospect. You can ignore hype if you wish — but then you’ll be able to say nothing about the gap between actual and expected earnings, and about how this gap is being manipulated and leveraged in capitalism for power ends.

I have been using your definition of hype. The definitions of E and EE that I rely upon above are cut-and-pasted from p. 189 of Capital as Power.

Your definition of hype implies hype has a value that is fixed at the time of capitalization but unknowable until the future.

Your Hype Index implies hype has a value that is variable. Upon closer inspection, however, each value of hype in the Hype Index actually relates to an independent and discrete act of capitalization (a series of forecasts). Whatever the Hype Index measures, it is not hype as you defined it because each value tests the accuracy of a different act of capitalization over a single year, not the accuracy over the long run of a single act of capitalization.

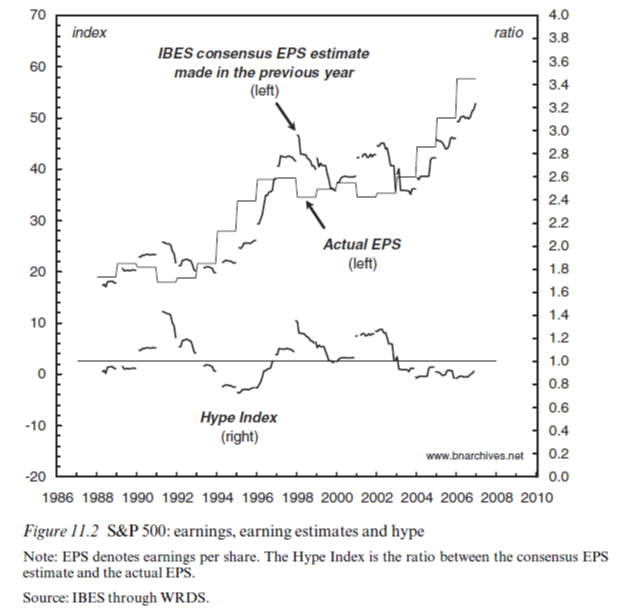

I have yet to see what insight the Hype Index provides. It seems to exist only to prove that “hype” exists. What has it told us about “how this gap [between actual and expected earnings] is being manipulated and leveraged in capitalism for power ends”? What does it tells about creordering? Fig. 11.2 and its related discussion provides no insight into these questions.

Like you, I suspect that stock prices are often manipulated and leveraged to create winners and losers, but I think this is easier to see when looking at specific companies and sectors of the economy, not the S&P500 generally. To me, the real tell of manipulation is a share price that is much greater than what a properly constructed free cash flow forecast determines to be the “intrinsic value” of the stock. In other words, manipulation is most likely to occur when the capitalization ritual appears to have broken down and cannot explain the actual share price or capitalization of a company. The price is not always right. Current examples of this phenomenon are Tesla and Bed, Bath and Beyond, but they are very different examples, with the former seeming to be the result of the manipulation of dominant capital, while the latter is the result of short sellers resisting dominant capital (the pricing mechanism is a two-edged sword). At one time, Amazon was greatly overvalued, as well, but eventually it lived up to the “hype” and is now fairly priced.

Perhaps I am completely misunderstanding CasP theory. Does CasP assume that the “price is always right,” that share price is always and everywhere determined by the discounting of future earnings, even when there is evidence to the contrary? If so, this would imply that capitalization isn’t really a ritual of capitalists, but an assumption of CasP. Does CasP assume that all capitalists agree that the price is right? If so, why would anyone ever sell? More importantly, why buy a stock that doesn’t issue dividends, which is the case for at least 60% of publicly traded companies, unless you expect the price to increase? Every stock sale has a seller, who is shorting the stock, and a buyer who is going long, i.e., every stock sale involves a disagreement about the future value of the stock.

Not a definition In CasP, we theorize that: (2) capitalization = expected earnings x hype / discount rate (Note that this is a simple expression, and that under different assumptions regarding the pattern of earning, the formula might differ.) Scott uses this equation to define hype, such that: (3) hype = capitalization x discount rate / expected earnings In my view, this is a logical error. Equation (2) isn’t true by definition. It is a theory (in this case, of capitalization), and since a theory can be wrong, it cannot be used it to define one of its components (in this case, hype).

Did they suspend the transitive property of equality without telling me about it?

I used equations (3) and (4), not equation (2), and I used them in the same basic manner that you do, only focusing on different identities.

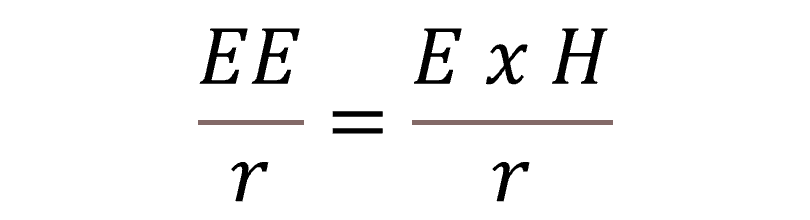

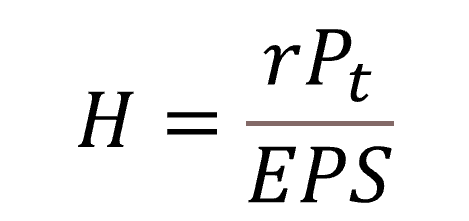

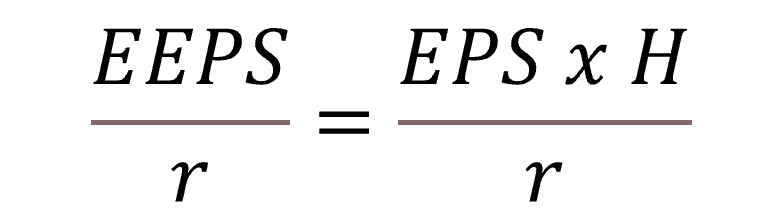

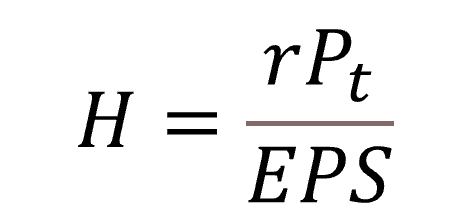

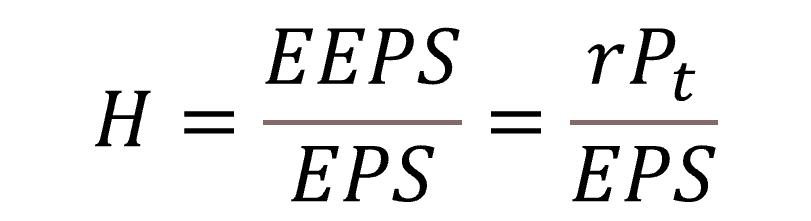

Now, if equation (3) can be expressed as:

According to the transitive property of equality, it can also be expressed as:

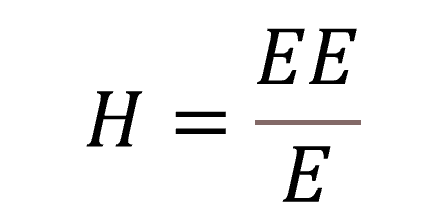

And then you can solve for H:

In the book, you chose a different expression of equation (3):

and then you solved for H

Now, let’s compare what I did with equation (4) to what you did.

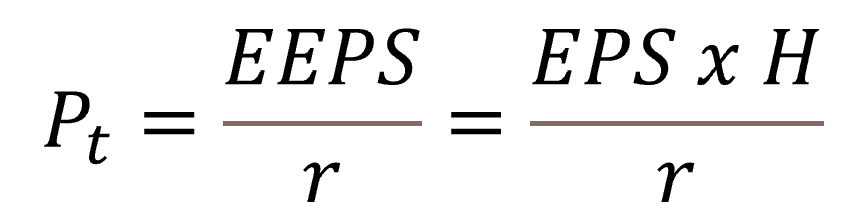

If we start with:

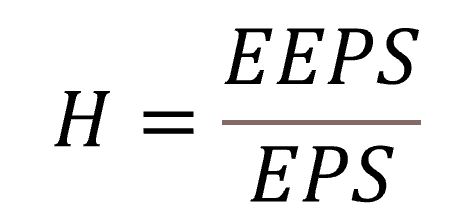

According to the transitive property of equality, I can rewrite equation (4) as

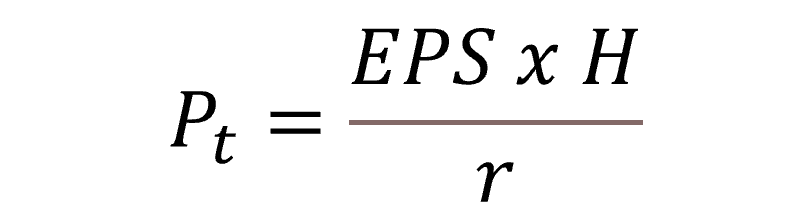

and then solve for H

You chose to rewrite equation (4) as:

and then you solved for H

We simply chose to solve for H using a different sides of equations (1) and (2) (as expressed via equations (3) and (4)). That is, we both used a constituent of a theory to define one of its own determinants.

S&P500: price and EPS The price index of the S&P500 is total market capitalization/number of shares. The EPS of the S&P500 is total earnings divided/number of shares. Both are free-float measures, and in that sense they weigh larger firms more heavily than smaller ones

That wasn’t the case in 2009, when Capital as Power was published. The price was market cap-weighted. EPS was not. When did S&P announce the change? I have not found the announcement, and the SP500 documentation doesn’t really say..

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

December 9, 2021 at 3:31 pm in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247317I am going to set aside my musings and other half-baked thoughts for the moment and just focus on the concept of “hype” as it is presented by Bichler and Nitzan in their 2009 book Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder.

To begin:

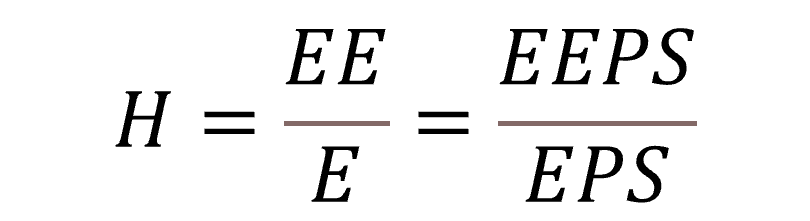

Summarizing

To reiterate, here, EE is the expected level of earnings (in perpetuity), while E is the actual level of earnings (in perpetuity), and EEPS is the expected level of earnings per share (in perpetuity) while EPS is the actual level earnings per share (in perpetuity).

Now, let’s look at the Hype Index of Figure 11.2:

The Hype Index does not measure hype, it measures forecast error. The Hype index cannot measure hype because we do not stand at the end of time, and so we cannot know the final value of EPS.

Is the Hype Index useful? Maybe. I can think of one way to test whether what it tells us is meaningful using readily available data. Equation 3 can be alternatively solved for H, as follows:

so

which implies that EEPS should always be equal to rPt, which I am pretty sure won’t prove to be true.

Alternatively, you can recalculate the Hype Index by dividing rPt from a year ago and by the actual EPS for the date in question. Both r (the expected rate of return of the S&P500) and Pt of the prior 12 months are known for or can be calculated for on a daily, weekly, monthly or annual basis. The Hype Index calculated this way should be identical to that shown in Figure 11.2.

I am pretty sure we will find, however, that dividing rPt of twelve months before by the actual EPS of time zero will not yield the same value for H because the value of Pt is based on the weighted average of capitalization of all components of the S&P500, while the EPS of the S&P500 is just a straight summation of all earnings and losses per share without consideration of the relative size of companies or their weighting in the index.

The term “hype” has a lot of baggage. On the one hand, it imputes a particular state of mind to whoever allegedly purveys it. On the other hand, it triggers cognitive biases in those trying to study the underlying phenomenon. The better term for the “Hype Index” is the “Forecast Error Index,” both because forecast error is what is measured and because it neutral and does not foreclose the consideration of potential root causes for the error other than “hype.”

Summarizing,

- Hype as defined by CasP is immeasurable because we can never know the “actual” EPS at the end of time.

- The Hype Index does not measure hype, it measures forecast error on a rolling 12-month basis. The validity of that measurement is unknown but can be tested/confirmed with an alternative method of calculating said error.

- We have no basis for assuming that “hype” is the reason for the forecast error, and we should avoid using labels that impute the state of mind of others, which is unknowable.

December 8, 2021 at 9:03 pm in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247315Here is a ProPublica report about how algorithms can be biased.

So, when we talk about the ritual of capitalization, we need to consider that the operators of an equation, not just the variables, can affect, if not dictate, the outcomes.

Who needs to put a thumb on the scale when the scale is the thumb?

December 8, 2021 at 5:15 pm in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247314Modern Finance has essentially introduced the institutional and systemic biases of dominant capital into how we understand Finance, capital, and the world, generally. In this sense, “hype” is a vector, not a scalar, and it is universal and not limited to the ritual of capitalization. The biases of dominant capital have both a magnitude and a direction, but the term “hype” implies ideas like “herd mentality” and “mania,” which obscure the real problem and prevent us from identifying capital’s biases, let alone measuring their magnitude or direction.

I might be misreading this, but is the relevance of hype dependent on whether it is only a ritual internal to a dominant group of capitalists? If dominant capitalists can differentially accummulate by stirring up herd mentality with such tactics as overly-optimistic earnings expectations, I might misunderstand the concern with hype being employable by any and all. If the root of hype is social-psychological, the ability to oversell with optimism or downplay with pessimism is universal — and certainly has a social origin before the Italian Renaissance and the bourgs. Yet, power is the root of a dominant class scaling the effects of hype, much in the same way that risk is not an exclusive concern of dominant capital.

I am questioning whether “hype” is even a thing. Certainly, I don’t believe hype is an “elementary particle” of capitalization, as asserted in CasP 2009, nor do I think hype as discussed in equations 3 and 4 is measurable, even though the “Hype Index” of Figure 11.2 of CasP 2009 claims to measure it in a way not suggested by either equation. To me, the closest thing that’s been done to measuring “hype” in the manner suggested by equation 4 of the book is the “Systemic Fear Index,” which suggests to me that perhaps “fear” and “hype” are two sides of the same confidence coin, that maybe what we are better off forgetting about “hype” and “systemic fear” and thinking directly in terms of measuring confidence, as power is confidence in obedience.

Jonathan and Pieter have convinced me that my view of “hype” may be too narrow, that I need to look beyond equations 3 and 4 and to what they see as effects of “hype,” however defined, such as herd mentality, etc., to understand whether the concept of hype is useful in understanding capital as power (and, clearly, I may be the only one questioning the value of hype, as defined in the book, to CasP analysis). So, in the quote above, I was thinking out loud about the possibility that “hype” is better viewed as a broad and pervasive assertion of power that shapes our understanding of the world. This is in-line with, and perhaps inspired by, my understanding of the origins of neoliberalism and the tactics neoliberals engaged in to make it safe to be a capitalist again.

I am reminded of the book The Mismeasure of Woman by Carol Tavris, which made the argument that culturally and historically, the measuring stick for women has been men. When “man is the measure of all things,” woman is forever trying to measure up. Using the white, Christian straight male as the metric for normalcy has generally been beneficial to all white males, but has not necessarily been good for everyone else (see, e.g., what many call “white privilege”).

Is it possible that dominant capital (or capitalists generally) have managed to establish pro-capital biases/metrics that we don’t even recognize as such, biases/metrics that we apply unthinkingly because they are embedded in how we have been conditioned to think? Again, I think the free cash flow valuation models compel what we view, in hindsight, as herd mentality, but the math is the math and has no mentality. If there is any herd mentality, it is in the commonly held but mistaken belief that the future is reliability knowable. What about the things we don’t measure, is there a reason for that? In the capitalist world, they like to say “if you can’t measure it, it doesn’t exist,” so have we been conditioned to not measure or overlook things that make capitalists uncomfortable?

This type of thinking is what led me to suggest that “hype” may be better understood as a set of pro-capital biases/metrics that are not only institutional, but internalized in everyone who is a member of a capitalist society. I don’t know if the right term is “social-psychological” because the phenomenon seems deeper and broader than that. These are things we all know and believe, sometimes without recognizing that we do, because of the culture we live in. It is more than propaganda or puffery (what I think of when I see or hear the word hype). Cultural capitalism, maybe?

I hope I managed to answer your question.

December 8, 2021 at 12:59 am in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247305Thanks for your thoughtful response, Pieter. You helped me to better understand your point of view about “hype,” which appears consistent with Jonathan’s, but, as you can see from my response to Jonathan, understanding does not equal agreement.

In the law, I was taught that you sometimes need to sacrifice precision for clarity, but as someone also trained as an electrical engineer I have difficulty applying the same lesson to what is supposed to be science. Pedantry is a feature of science, not a bug.

–Scot

December 8, 2021 at 12:34 am in reply to: Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization? #247303Thank you Scot and Pieter. 1. Can hype be observed/measured? Hype = EE / future earnings We can observe expected earnings EE by asking those who expect them what they expect. In retrospect, we can know what the future earnings (E) turned out to be. By dividing one by the other, we get Hype. In practice, this computations can be complicated because we have to ask everyone who expects and collect eventual earnings data, but these are practical rather than conceptual difficulties. Backward measuring ‘earnings all the way to eternity’ is of course impossible since eternity is never reached, but earnings over the past 100 or 200 years can be measured — and that should do, since discounting reduces the significance of more distant observations. So no, hype isn’t like utils and SNALT. It can be measured, unambiguously, in principle; and, with enough resources, it can also be measured in practice.

But the future earnings (E) of Equations 1 and 3 of the book (CasP 2009) is asserted as representing ALL future earnings in perpetuity, which we have yet to (and cannot possibly) measure because they have not come into being yet. Interestingly, the trend line of the EE/actual ratio (aka the Hype Index of Figure 11.2 of the book) over time, on average, appears nearly equal to 1.0, which implies accuracy, not error (I think?).

In any event, according to equation 3 of the book, H = rKt/E, and according to equation 4 of the book, H=rPt/EPS.

The “Hype Index,” or EE/”actual” future earnings, does not measure Kt, so it says nothing about H according to equation 3 of the book.

On the other hand, you have measured Pt/EPS as part of constructing what you call the “Systemic Fear Index,” which focuses on the correlation between P and EPS. Perhaps the common explanation for “Hype” and “Systemic Fear” is confidence in obedience, i.e., power itself? If so, do we need “hype” as a separate concept?

FYI – I have been tearing apart the “capitalization” methodology of one value investor pay-site with the intent of publishing their methodology as compared to CasP’s version of capitalization. The site’s primary goal is to determine whether a stock is undervalued or overvalued, i.e., the site’s goal is to identify stocks whose price objectively does not make sense. Thus, instead of creating “hype,” the straightforward application of free cash flow “capitalization” models can identify the presence of “hype,” which means that hype is not an elementary particle of capitalization but is exogenous to it.

2. Is hype important? We think it is. The example we give in Figure 11.2 of our book shows that the two-year earnings projections of analysts contain very large errors, and that these errors tend to be systematic and herd-like. Think of what the errors might be for 10-, 50-, or 100-year projections. The key point is that these large ‘errors’ are often leveraged and indeed creordered by dominant capital, and in premeditated ways, and they often have significant consequences for society (think of the roaring twenties turning into the Great Depression and WWII, or of the dot-com and subprime crises having set the stage for the current global turmoil.)

The fact that all earnings forecasts start with the same data regarding prior earnings and growth makes it easy, in hindsight, to misidentify earnings forecasts as “herd behavior.” People applying the same mathematical models to the same data with slightly varying assumptions (where judgment is allowed) are going to reach similar conclusions. The real question is why do these mathematical models exist?

We know, for example, that CAPM is complete junk, and yet it is central to the valuation approaches of at least 70% of all analysts. How and why is that?

Modern Finance has essentially introduced the institutional and systemic biases of dominant capital into how we understand Finance, capital, and the world, generally. In this sense, “hype” is a vector, not a scalar, and it is universal and not limited to the ritual of capitalization. The biases of dominant capital have both a magnitude and a direction, but the term “hype” implies ideas like “herd mentality” and “mania,” which obscure the real problem and prevent us from identifying capital’s biases, let alone measuring their magnitude or direction.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

November 30, 2021 at 11:07 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247260The other possibility is that economists simply have no idea what they’re talking about.

The answer correct is: mainstream economists are lying liars who lie.

The direction of their “errors” is too consistently in favor of capital to be anything other than purposeful on someone’s part.

November 29, 2021 at 10:07 pm in reply to: Regulation as support structure for the Power of Capital #247246Without getting into the details just yet, because I’ve still got a lot of reading to do on the subject, I want to propose here that Regulatory legislation falls into a few very broad categories

The categories you list are potentially useful and informative, but they are not always easy to delineate in practice. ‘Regulation’, like every other important form of capitalist creordering, has multiple consequences, which, in principle, can affect every one of your categories. In order to make this classification useful, we need not only to theorize it, but also to research its multiple consequences.

I was going to mention this, as well. For example, much of the “regulation” we see in the U.S. today is actually being performed by courts (not legislative or administrative bodies), particularly by judges influenced by the Law and Economics movement, which I’d argue is the dominant legal philosophy today.

If I were to start in on this kind of project, I would focus on the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and follow the thread of federal antitrust law and enforcement through to the present day. We know many of the consequences, e.g., the rise of the modern corporation to avoid antitrust laws, breaking up AT&T, curtailing Xerox’s IP rights, etc., and we can find others through applying CasP logic. Moreover, the Sherman Antitrust Act began as a standalone, bright line law whose enforcement was gradually pushed to administrative agencies, many of which have become captured by the industries they are supposed to monitor.

Other potential areas/topics would be environmental protection laws and copyright laws (there is a massive schism in patent law that has shaped an oddly schizophrenic regime of patent enforcement, but that’s interesting, too; how does dominant capital deal with civil wars among capitalists?), the histories of which are pretty well-established and are likely to yield new insights if subjected to CasP analysis..

In our view, anything that is conditioned and creordered by the logic of capital as power — including capitalists of all types, workers, corporations, labour unions, governments, NGOs, international organizations, crime networks, etc. — can be theorized and researched by CasP. But things that lie outside this logic — particularly alternatives to it — cannot be. The line separating these two categories of course is open to debate.

That is helpful. Thank you.

I view CasP’s logic as tailored to the dominant capital and capitalism of today, but I don’t think the capitalism that existed prior to the modern limited liability corporation or stock markets lies outside of that logic, if it is modified to account for the limited number of tools in the creorder toolbox. Capitalist power is fractal, which involves self-similarity, not exact replication. This issue is what prompted my question: is it fair to translate/modify CasP’s logic to account for differences in the stage of capitalism’s development or the position of the capitalist within the capitalist hierarchy?

For example, I think it would it be fair to consider the financial wealth of an individual capitalist as her “capitalization.” Although she, herself, is not divisible into shares and vendible on a stock market, her financial wealth is denominated in monetary units whose value is determined by the discounting/capitalization ritual, which was true before stock markets were well established (e.g., when “stocks” were typically bonds and other debt instruments, not shares of corporations). Thus, CasP’s logic still applies to the individual capitalist, although “differential accumulation” likely means something other than what it means for dominant capital, e.g., there are no depth or breadth regimes for the individual except indirectly.

November 29, 2021 at 12:43 pm in reply to: Regulation as support structure for the Power of Capital #247241Pieter,

You may want to focus on the developments of a specific time period. The reality is the laws of England and America at the dawn of capitalism were deemed unfriendly to business, i.e., they restricted dominant capital because they restricted everyone, not because of public outcry, and the law was gradually transformed over time to loosen restrictions on dominant capital, culminating in the late 19th century at a time when the so-called legal positivists were ascendant in law. In the U.S., this is when resistance to dominant capital swelled and the Sherman antitrust act was born. (The Horwitz books, linked to below, are a great resource for understanding this phenomenon.)

The time after the beginning of the 20th century around the birth of the administrative state under Democratic administrations (FDR for certain, but I believe Wilson ushered in the era) should be of great interest. It would be interesting to read the original scholarship advocating administrative agencies as rule setters over the traditional bright line rules.

Of particular interest to me is the history behind the formation of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). As general counsel of two publicly traded companies (and corporate secretary of a third), I became convinced that the SEC existed to support businesses, not to restrain them. All you had to do was make sure you were in a “safe harbor,” of which there are many built into the law, for whatever action you took. They made it easy.

Personally, I believe that most, if not all, administrative agencies functioned correctly as rule makers and enforcers, but that those institutions have degraded over time, a circumstance hastened over the last 50 years by neoliberal policymakers (see Bork and antitrust).

–Scot

Here are some books that provide a strong foundation for your topic:

Berle and Means The Modern Corporation and Private Property

John Commons Legal Foundations of Capitalism

Morton Horwitz’s The Transformation of American Law (both volumes)

Katharina Pistor’s The Code of Capital

Adam Winkler’s We The Corporations

Is CasP theory limited to describing the behavior/power of dominant capital?

If not, to what extent does CasP theory explain the behavior/power of capitalists, generally, individually and with respect to dominant capital?

If so, is there any reason why CasP theory cannot be extended to capitalists, generally and individually, as distinct from the corporations that form the core of dominant capital? (Capitalists are not capitalized, only firms are capitalized, and differential capitalization only results in differential accumulation for the individual capitalist when he locks in gains by selling his shares.)

Pieter,

Thanks for your post. I am likely to have additional replies with references to sources that might have additional clues to help you fill in your timeline, which is already pretty good, but I wanted to focus this reply on the different uses of the term “capitalization” as well as how discounting is actually used in Finance compared to CasP’s simplification of it (which is fair in broad terms but leads to dismissive criticism from finance bros who encounter CasP discussions for the first time and don’t know that CasP is using a common term in a unique way).

CasP uses the term “capitalization” in a very particular and peculiar way compared to mainstream finance. Most typically, “capitalization” refers to the mix of debt and equity of a corporation, its capital structure, not its “market capitalization.” Also, investors/capitalists don’t necessarily believe the “market capitalization” (share price x no. of shares) reflects a firm’s true value, which is precisely why the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis were developed to test whether or not the share price is actually at fair market value. There is no “hype” variable in CAPM or DCF analysis, for example.

The ah-hah moment for me as an executive of a publicly traded company (a role I’ve played three times but never again) is that CAPM is used to equate an investment in stock to an investment in bonds. I concluded that, as a manager of a publicly traded company, my job was to manage the company as if it were a bond of infinite duration with a yield greater than a benchmark rate. The goal was not to maximize profits in a given quarter but to simulate continuous earnings growth at a rate equal to or greater than the benchmark rate.

The simple fact is that discounting and compounding are the inverse of one another. Some of the earliest examples of the “capitalization ritual” in B&N’s 2009 CasP book relate to determining an offer to purchase a loan or bond with remaining interest payments is a fair one. A straightforward discussion of the relationship between discount rates and rates of compounding interest may be found here:

A true DCF analysis of the fair value of a stock is a bit more complicated than the simple discounting formula because you have to first calculate future earnings, which is not as simple or straightforward as often discussed in CasP papers, at least for value investors who take valuation (which CasP typically equate with capitalization) seriously.

That said, CAPM is utter crap. It doesn’t work, and its authors have admitted that it doesn’t, but that doesn’t prevent 70% plus of Wall Street analysts from using the approach. CAPM has become a normative myth of Finance to perpetuate a pricing model that CasP’s “capitalization ritual” gets right in big-picture terms.

One of the things I have been working on for the CasP community is detailing a typical methodology, with excel spreadsheet templates, of how CAPM is used along with other common finance tools/approaches to yield a typical DCF fair market valuation of a stock. The goal of this project is to provide a deeper understanding of differential accumulation and differential capitalization, which to me are different but often are presented as the same thing. The power of the owners (capitalists) and the power of the firms (corporations) are different and are expressed differently.

I was unaware of the Open Science Framework (or that Elsevier owns SSRN). Thanks for the link!

–Scot

November 21, 2021 at 10:26 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247201There are two ways to increase differential markup: (1) reduce your costs, including your cost of capital, and (2) increase your prices.

The mid-80s started a fundamental shift in Finance’s attitude towards the cost of captial/credit. We saw both the beginning of a reduction in the 10Y Treasury rate (which reduced the Fed Funds Rate and corporate costs of capital accordingly) and the rise of credit cards whose interest rates were not anchored by the Fed Funds Rate to expand the purchasing power of consumers without increasing their pay.

I think the Werner paper I linked to in a previous post is very important to understanding the broader outlines and consequences of reducing the cost of capital on GDP. What’s missing is research on consequences of easy credit for consumers at high interest rates unconnected to corporate cost of capital.

November 15, 2021 at 7:57 pm in reply to: Modelling the State of Capital (or At Least Trying to Do So) #247183Looking forward to seeing your ideas enable new research.

Me, too. That said, I think the research areas probably need to expand beyond political economy, and even with political economy, they need to pursue other paths, perhaps towards new “indices.”

One area for research is the law, which is where my strength resides (and I’ve been researching the history of the law as it relates to many CasP issues for over a decade). Markets and Finance would not exist, but for the law.

Another area, which you’ve mentioned previously, is accounting. I’ve actually started looking at the history of depreciation and amortization and accounting, generally, mostly trying to track down how/why the term “capital assets” came into usage (it certainly predates Smith, who gets a lot of blame from you and others).

A third area is modern finance. Someone or something was behind the investment in developing (100% wrong but widely used theories such as) CAPM, for example. I’ve actually spent a lot of time over the last decade studying this, as well, but a lot of the work y’all have done in CasP leads me to believe Finance discovered some connection between cost of capital, return on capital and GDP growth that changed everything, resulting in what we’ve seen in the world economy beginning probably as early as the 1960s.

“Research” in these first three areas does not necessarily look like what CasP normally does. Something that is closer to CasP’s home is attempting to understand the causal connection, if any, between (1) interest rates for corporate debt, (2) corporate profits (and growth rates) and (3) GDP growth. (The answer could be in CAPM itself, as the “risk free rate” is the benchmark against which all other interest rates are set.) While free resources like FRED have a lot of the data, they are unlikely to have all that is necessary to study this issue. I am currently developing some ideas on what research can be done by me in this area using the resources I have, and will post those up in the Research section of the forum. Maybe others will know better resources. Again, while I can do some basic data analysis, I am not a data analyst by any stretch.

P.S. I don’t know how familiar you are with the so-called Coase Theorem, but taken to its logical conclusion, it destroys our understanding of private property and would replace it with something else that vastly increases capital’s power. Basically, the Coase Theorem argues that the owner of any particular property ought to be he who can best exploit it economically, as that ensures the greatest utility for society as a whole. What is scary is that the Coase Theorem and other economic ideas such as Pareto Efficiency are central to the Law and Economics movement and have already begun reshaping the law in ways that always further advantage capital over everyone else.

-

AuthorReplies