Wal-Mart’s Power Trajectory

A Contribution to the Political Economy of the Firm

JOSEPH BAINES

March 2014

Abstract

This article offers a power theory of value analysis of Wal-Mart’s contested expansion in the retail business. More specifically, it draws on, and develops, some aspects of the capital as power framework so as to provide the first clear quantitative explication of the company’s power trajectory to date. After rapid growth in the first four decades of its existence, the power of Wal-Mart appears to be flat-lining relative to dominant capital as a whole. The major problems for Wal-Mart lie in the fact that its green-field growth is running into barriers, while its cost cutting measures seem to be approaching a floor. The article contends that these problems are in part born out of resistance that Wal-Mart is experiencing at multiple social scales. The case of Wal-Mart may tell us about the wider limits of corporate power within contemporary capitalism; and the research methods outlined here may be of use to scholars seeking to conduct political-economic research on the pecuniary trajectories of other major firms.

Keywords

capital as power, corporate power, differential accumulation, differential capitalization, power theory of value, Wal-mart

Citation

Joseph Baines (2014), ‘Wal-Mart’s Power Trajectory: A Contribution to the Political Economy of the Firm’, Review of Capital as Power, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 79-109.

By some measures Wal-Mart is the world’s largest corporation. The retail giant has garnered more annual revenues than any other business for seven of the last ten years. And with 2.2 million employees, it has about as many people in uniform as the People’s Liberation Army of China. However, since the turn of the twenty-first century the retail behemoth has undergone a massive slowdown in its pecuniary growth. Indeed, at the beginning of the 2000s, Wal-Mart’s revenue was increasing annually by almost 16%. By 2013, year-on-year revenue growth had fallen to less than 6% (Gara 2013). Wal-Mart’s troubles are perhaps typified by its increasingly antagonistic relations with its employees. To express their dissatisfaction with the firm, around 400 workers went on strike for a day just before Thanksgiving for the second year running. Protests were held in up to 1500 locations and over 100 people were arrested (Eidelson 2013). The episode represents just an eruption in the conflict within and against Wal-Mart. The task of this paper is to trace the underlying tectonics of resistance to the company’s power.

A number of authors have already sought to make sense of Wal-Mart’s growth path and the challenges the company is currently experiencing. In the field of management studies, the retail ‘life-cycle’ concept has been used to analyze the interaction of CEO leadership, organizational structure and market complexity in a stage-model approach to the shifts that Wal-Mart has undergone from rapid expansion to contemporary slowdown (Palmer 2005). Other studies move away from the ‘life-cycle’ concept and zone in on the more specific organic metaphor of ‘maturation’. In these investigations, the role that market saturation plays in stymieing Wal-Mart’s pecuniary advance is emphasized. As these studies suggest, the causes of market saturation are manifold: from declining population growth, to sluggish consumer demand, to rival retailer consolidation (Serpkenci & Tigert 2006). Additionally, business studies scholars have shifted the focus from the consumer-side of Wal-Mart’s operations to the role of logistics development in the shaping of the company’s trajectory (Roberts & Berg 2012). Meanwhile, proponents of global value chains (GVC) analysis have given particular attention to the global shifts in Wal-Mart’s relations with its suppliers (Gereffi & Christian 2009). And there is now a burgeoning body of work on Wal-Mart’s internationalization (Aoyoma 2007; Christopherson 2007; Durand & Wrigley 2009). Perhaps the most impressive appraisal of Wal-Mart’s evolution has been offered by the labor historian, Nelson Lichtenstein. In particular, his book Retail Revolution: How Wal-Mart Created a Brave New World of Business brings forth a detailed analysis of the transformation in US labor relations as they appertain to the retail sector. Lichtenstein combines this analysis of labor relations with a broad, historical examination of Wal-Mart’s supply chain changes, logistical innovations, stuttering internationalization and domestic slowdown. The result is an appraisal of the firm that is both rich and holistic.

Given these multiple contributions, one would be excused for asking whether the analysis of Wal-Mart’s growth trajectory has itself reached saturation point. Will another contribution create new currents in the pool of literature on Wal-Mart? Or will it unceremoniously sink, like so much scholarship, into the stagnant sediment of forgotten thought? This article has been written out of the conviction that a value-theoretic analysis of the company’s evolution is required. Indeed, although many of the above-mentioned contributions bring rich insights to bear, they are not sufficiently informed by an account of what exactly Wal-Mart is accumulating. The absence of an explicit value-theoretic approach to Wal-Mart’s contested expansion is perhaps unsurprising. In its unreconstructed form, the liberal approach to political economy views the market as a sphere of freely transacting atomistic agents and thereby conceptualizes power as an external distortion to the equilibrating cadence of supply and demand. This exogenous reading of power and the conception of the economy as a realm of atomistic individualism is clearly inimical to the study of an organization as vast and as powerful as Wal-Mart. Similarly, the analytical tools of classical Marxist political economy appear to be ill-disposed to elucidating Wal-Mart’s growth trajectory. In fact, if we follow the Marxists in viewing capitalism as a mode of production, then the most important labor conflict in recent American history – that between Wal-Mart and its workers – is just a sideshow, played out in the ‘sphere of circulation’ where value is not ‘extracted’ but merely ‘realized’.

Needless to say, few analyses of Wal-Mart fit neatly within the bracket of classical Marxism or free-market liberal political economy. The GVC approach, for example, draws on a confluence of influences, including world systems theory and Schumpterian economics. This theoretical eclecticism makes GVC analysis seem better suited than both unreconstructed liberal theories and classical Marxist theories of capital to analyze Wal-Mart’s development. In particular, the notion that ‘barriers to entry’ redistribute ‘value-added’ in supply chains points to the importance of power in the capitalist political economy. Moreover, the GVC approach provides useful ideal-types that help the researcher better make sense of the role of ‘lead-firms’ in commandeering commodity chains. The most illuminating ideal-types are perhaps the ones that were originally conceived: those of ‘producer-driven’ and ‘buyer-driven’ commodity chains, with Wal-Mart convincingly presented as a paradigmatic lead-firm of the latter (Gereffi & Korzeniewicz 1994).

However, given its intellectual lineage in mainstream economics, the GVC approach implicitly cleaves to a hedonic conception of value. Accordingly, its emphasis on the role of power in shaping developmental outcomes in value chains sits awkwardly with its underlying view of capital (Baines 2014). To be sure, if capital is considered a hedonic entity accumulated by utility maximizing agents, then power can only be incorporated into the analysis a posteriori. Thus, while GVC analysts have a good deal to say about how value is redistributed in commodity chains, some of the leading exponents of the GVC approach have themselves admitted that the question of how value is created “has hardly been discussed at any stage of the development of GVC analysis” (Gibbon, Ponte & Bair 2008, p.332). Ironically, ‘value’ remains the under-theorized core of the global value chains schema.

Perhaps the most interesting analysis of retail power in recent years has been provided by Céline Baud and Cédric Durand (2012). In an empirically rich investigation of the ten largest retailers in the world, including Wal-Mart, Baud and Durand argue that the retail internationalization wave of the early 2000s was instigated by the slowdown in revenue growth in retailers’ domestic markets. And once the possibilities of exploiting the ‘first-mover’ position in foreign markets had been exhausted, retail firms increasingly turned towards ‘financializing’ their activities as a way of increasing shareholder returns on equity. Despite the impressive range of data presented in Baud and Durand’s article, its contribution to understanding Wal-Mart’s trajectory is limited by a number of factors. Firstly, the authors cover only the period from 1990 to 2007, and therefore the vista of historical inquiry is rather narrow. Secondly, while some of the arguments that the authors make may apply to the ten firms as a group, they are often misleading when applied specifically to Wal-Mart. In fact, during the period under discussion, the proportion of financial assets out of Wal-Mart’s total assets has only increased from approximately 8% to 11%, so the notion that the company has been ‘financialized’ seems overstretched.1 And thirdly, at the risk of sounding repetitive, the authors fail to explicate a clear conception of value. Although they invoke VI Lenin’s and Rudolf Hilferding’s analyses of imperialism to explain how ‘overaccumulation’ in retailers’ domestic markets led to an expansion of investment abroad, they do not unpack these analyses. But it is worth noting that even if Lenin’s and Hilferding’s ideas played a more prominent role in the framing of Baud and Durand’s argument, the criticism that their investigation lacks an adequate value-theoretic grounding would still hold. For while Lenin and Hilferding gestured away from Marx’s labor theory of value in their analyses of imperialism, neither offered a coherent value theory to replace it (Nitzan & Bichler 2012a).

Every study of accumulation needs value-theoretic foundations, and as I seek to demonstrate, the power theory of value, propounded by Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, offers exciting possibilities in this regard. As Nitzan and Bichler argue, value in the context of capitalism is governed by the metric of capitalization: the risk-adjusted discounting of expected future earnings to their present magnitude. Additionally, the capacity of corporations to augment future earnings and reduce risk is determined by their power to restructure social reproduction for their own pecuniary purposes, over and above the pecuniary purposes of other corporations, and against social opposition. It follows that value and power are figuratively identical. Moreover, as power is inherently differential, value should be understood not as an absolute entity but as a relationship between entities (Nitzan & Bichler 2012b, p.24). From this viewpoint, the problem that GVC analysts have in conceptualizing both the creation and distribution of value recedes into irrelevance. To be sure, if value viz. power is inherently relational, value-creation is not prior to value-distribution; instead, value-creation and value-distribution are one and the same social process.

This article is divided into four sections. The first section outlines the power theory of value and demonstrates how it may enable researchers to better comprehend Wal-Mart’s evolution in the last four decades. In particular, I sketch out Nitzan and Bichler’s conceptualization of the relative extensiveness of a firm’s control over social reproduction – its ‘differential breadth’; and the relative intensity at which this control is enforced – its ‘differential depth’. I then connect this reading of firms’ differential breadth and depth to Nitzan and Bichler’s more recent notion of the asymptotic trajectory of corporate power. The second section seeks to make sense of Wal-Mart’s golden age of rapid growth by offering new differential and longitudinal measures to gage the power that firms command over their supply chains. The third section examines the slowdown in Wal-Mart’s accumulation of capital viz. power in the 1990s and 2000s. It suggests that this slowdown can in part be understood in relation to the mounting resistance that Wal-Mart has faced, from its own workers, from community organizers, from consumers, from rival retailers and from those toiling in sweatshop conditions for Wal-Mart’s suppliers. Given the space constraints, the analysis is principally limited to the transformations in Wal-Mart’s US retail operations, in its logistical innovations and in its supply chain relationships. However, the concluding section proposes broadening the inquiry by considering the internationalization of Wal-Mart’s retail operations. It suggests that, despite Wal-Mart’s foreign expansion, the company’s accumulation appears to be approaching a quantitative limit, or asymptote, that it may be unable to surpass. As such, the aim of this article is not simply to accentuate aspects of power alluded to in previous analyses of Wal-Mart’s trajectory, but to make the study of power the organizing principle of investigation. In so doing, I plan to contribute to the existing literature on the dynamics of corporate power in contemporary capitalism, and to point to empirical methods that may help researchers engage in political-economic investigations of other major firms.2

I The Power Theory of Value

Building in part on Thorstein Veblen’s theory of business sabotage, Nitzan and Bichler argue that all profits stem from the institution of private ownership as it confers upon owners the power to exclude others from using their assets. Without private ownership there could be no restriction on the use of goods; and without restriction on the use of goods, goods could not be priced into commodities that yield pecuniary earnings. But exclusion within capitalism goes way beyond matters of pricing power. It entails the delimitation of the manifold possibilities of human creativity and social development down avenues propitious for profit growth. The foundational exclusionism of private ownership is evidenced in the etymological roots of the word private: ‘privatus’ and ‘privare’ – Latin for ‘restrict’ and ‘deprive’ (Nitzan & Bichler 2009). Thus, while GVC analysis views exclusion, as manifest in the erection of ‘barriers to entry’, to be ultimately epiphenomenal to capital; the power theory of value takes exclusion to be integral to capital’s social significance.

As Nitzan and Bichler argue, unlike modalities of exclusion that were widespread in the past such as feudal relations of custom and fealty, capital encodes exclusion with a universalizing quantitative syntax. The generative grammar of this quantitative syntax is capitalization: the formula through which risk-adjusted future earnings are discounted to their present value. Nitzan and Bichler’s theoretical innovation lies in recasting the discounting formula from the perspective of what they call dominant capital: the major firms and government entities at the core of accumulation. Capitalization is all encompassing. Any power process that seems to bear on the future earnings of any given asset is factored into the capitalization formula. And since dominant capital actively seeks to re-shape power processes in a manner that augments future income and reduces risk, market value is itself the master signifier of business power. This insight has far-reaching implications. Instead of being a mere tool that enables owners to passively measure the value of their ownership claims, capitalization is the means through which dominant capital appraises its capacity to actively restructure society.

However, the CasP approach is not just influenced by Veblen’s analysis of business, but also by Karl Marx’s reading of GWF Hegel. As Marx argues, social reality is constituted by negation. Just as exclusion is predicated on the threat of its transgression, power presupposes resistance. Following on from this presupposition, the CasP framework suggests that corporate agency does not exist in a vacuum, but rather in a force-field of social struggle. Thus, in the final analysis, capitalized power represents “confidence in obedience” (2009, 17). It is the quantitative analogue that tells the researcher how certain dominant capital is of the underlying population acquiescing to its pecuniary advancement. This insight has profound implications for how we view the space within which business operates. Instead of following neo-classical economists in taking power to be a distortion external to the market, the CasP framework suggests that the market is itself a mechanism of power. As such, the researcher should consider every social process where the dynamics of control and resistance bear on the pecuniary earnings of business. These dynamics encompass, but are by no means limited to, ‘the sphere of production’ privileged in Marxist political economy. Nitzan and Bichler draw on the concept of the hologram to explicate this notion: power emanates from each and every part of the whole; and the overall power shifts within the whole reflect back on each and every part.

Due to this relational conception of power, Nitzan and Bichler argue that firms’ pecuniary operations should be understood in relative rather than absolute terms. This relativity has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. On the quantitative side, it is indicated by the fact that corporations do not seek to reach a ‘profit maximum’ (which, in Nitzan and Bichler’s view, is conceptually indeterminate). Instead they benchmark their own performance in relation to the average performance. And on the qualitative side, the relativity is manifest in the fact that different groups of corporations constantly seek to transform myriad institutions of social order, against resistance, so as to augment their power over and above the power of other business groups.

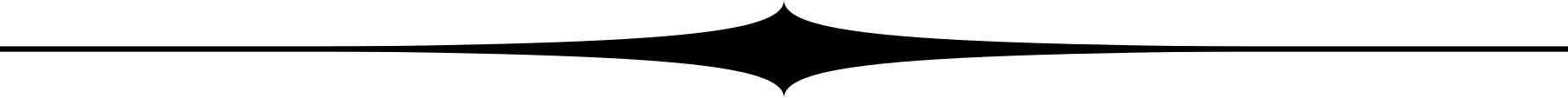

Through charting the long-running historical correlation between earnings per share and stock prices in the S&P 500 dataset, Nitzan and Bichler show that current earnings are used by investors as the central guide for discounting expected earnings to present value (2009, p.186). Thus, differential profit growth is the main long term driver of differential capitalization growth. But what propels differential profit growth? Observing that a firm’s earnings can be calculated as the product of the number of its employees and its average earnings per employee, Nitzan and Bichler argue that companies can augment their differential profit in two main ways: i) by increasing their employee numbers faster than the average; or ii) by increasing their profit per employee faster than the average. Moreover, there are a variety of ways in which firms can attain more employees and more profit per employee. This schema is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Axes of Corporate Power.

The breadth axis of pecuniary growth refers to the firm’s overall employee numbers. Early on in the development of firms, breadth expansion usually takes the form of green-field development. However, as firms become larger in size they are increasingly able to raise capital to buy up other firms through merger and acquisition. The depth axis refers to the firm’s profits per employee. Increased depth can be achieved through cutting costs, via operational efficiency gains and lower input expenses; or through oligopolistic price rises. As with mergers and acquisitions, oligopolistic price rises are characteristic of larger firms’ operations. This is because firms usually have to be of a significant size in order to engage in successful collusion. But as Nitzan and Bichler argue, the same does not apply to cost cutting. Rather than just being the preserve of dominant business, cost cutting is a ubiquitous feature of corporate strategy. New and improved production techniques easily spread from one firm to another; moreover reductions in input costs are usually not restricted for the benefit of one firm. As such, Nitzan and Bichler contend that in the long-run, cost cutting enables corporations to merely ‘meet the average, not beat it’ (2009, p.363).

According to the CasP framework, the differential accumulation of dominant capital as a whole is achieved primarily through countercyclical waves of oligopolistic price rises and mergers and acquisitions. However, as Nitzan and Bichler argue, the patterns of dominant capital as a group may not be representative of how individual firms have augmented their own pecuniary earnings. This insight is certainly true in relation to Wal-Mart. In terms of depth, downward ‘price leadership’ rather than upward price collusion has defined its business model of lean retailing. It is thus primarily through cost cutting that Wal-Mart has sought to increase its profits per employee. In terms of breadth, for much of its history Wal-Mart’s preponderant means of increasing its organizational scale was not mergers and acquisitions but green-field investment. And rather than operating counter-cyclically as with the breadth and depth waves of dominant capital as a whole, Wal-Mart’s cost cutting and green-field investment have proceeded in a coeval and symbiotic manner. This symbiosis can be seen in the ‘virtuous cycle’ of differential profit growth in which relatively high sales volume finances relatively low-margin pricing and relatively low-margin pricing drives relatively high sales volume.

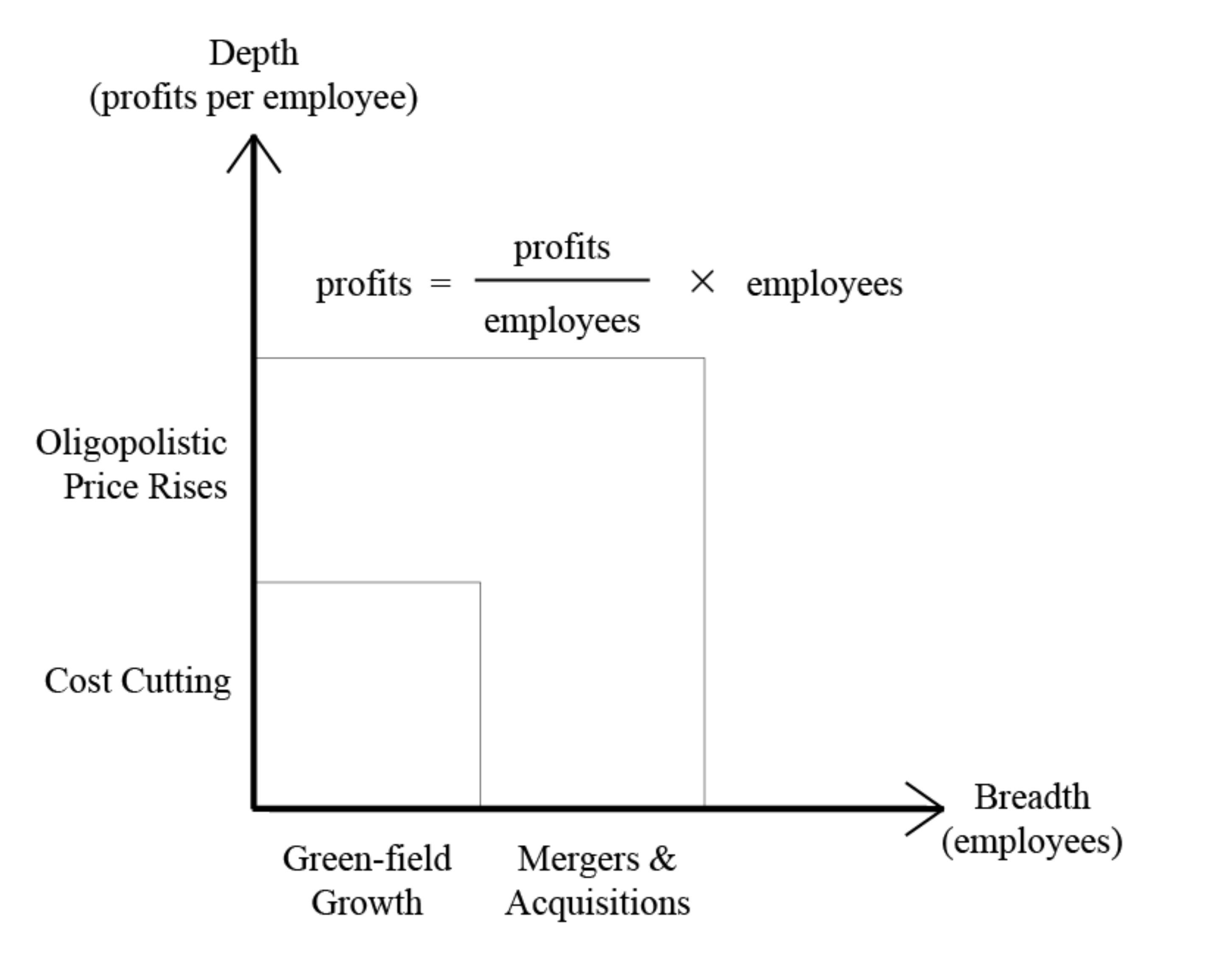

With some key aspects of CasP’s theory of accumulation sketched, we can now begin to trace the historical power trajectory of Wal-Mart. Figure 2 (see next page) offers the starting point of the empirical analysis. In what may be the first explicit quantitative explication of Wal-Mart’s power trajectory to date, the chart depicts the firm’s capitalization and profit relative to the average corporation within dominant capital, with both series plotted against a logarithmic scale. The proxy I use for the dominant capital benchmark is the Compustat 500 – the 500 largest firms by market capitalization listed in the .

Three major observations can be made from the chart. Firstly, the growth in differential capitalization and differential profit of Wal-Mart are very tightly correlated. This strong correlation underlines the importance of understanding current earnings as driving the long-term increases in the capitalization of the company. Secondly, the figure clearly shows that the period spanning from the late 1970s to the early 1990s represents a true golden age for Wal-Mart. Indeed, in 1975, the market capitalization of Wal-Mart is just one-tenth of the average firm in dominant capital, but in less than two decades the relative capitalization increases almost one hundredfold, so that by 1993 Wal-Mart’s capitalization is over nine times larger than the average dominant capitalist firm. Thirdly, from the early 1990s onwards Wal-Mart’s capitalization appears to oscillate below a differential ceiling, reaching a peak in 2003 and then trending downward slightly for all but two of the following ten years.

These insights on Wal-Mart’s differential pecuniary trajectory may be related to Nitzan and Bichler’s recent analysis of the possible limits on the pecuniary growth of dominant capital as a whole (2012b). In this analysis, Nitizan and Bichler suggest that dominant capital may be reaching an ‘asymptote’ – a pecuniary power limit that dominant capital cannot surpass. This focus on pecuniary limits is grounded in their understanding of capital accumulation as a process of relative gain. From this view, the greater the share of profits that dominant capital strives to secure, the more resistance it will encounter. The more resistance dominant capital encounters, the more force dominant capital will have to project on society in order to retain its power. And the more force dominant capital projects on the rest of society, the greater the potential for severe dislocation and concomitant backlash.

Figure 2: The Differential Capitalization and Differential Net Profit of Wal-Mart.

Note: Differential capitalization is the ratio of Wal-Mart’s market value to the market value of the average corporation in the Compustat 500. Differential net profit is the ratio of Wal-Mart’s net income to the net income of the average corporation in the Compustat 500. The Compustat 500 is the top 500 firms by market value listed in the United States.

Source: Wal-Mart and Compustat 500 net income and market capitalization data from Compustat through WRDS. Series codes: NIQ; PRCQ and CSHOQ.

To the extent that a corporation as vast as Wal-Mart can be seen as a microcosm, it is perhaps a microcosm of this process. As stated in the introduction, the company has recorded the highest revenues out of any firm in the world for seven of the last ten years. Wal-Mart is thus positioned at the apex of dominant capital. And according to the data presented in Figure 2, if there is an asymptote for the company’s pecuniary growth, it seems to be around a differential capitalization ratio of 10, or 2% of the profits secured by the Compustat 500. In this respect, the CasP approach furnishes us with the means to make sense of the power dynamics behind the process that scholars investigating Wal-Mart have euphemistically described as ‘maturation’. Such an organic metaphor elides the resistance, both implicit and explicit, that stymies the onward advance of corporate power. In much of what remains, I draw on the power theory of value to bring this mounting resistance into full view.

II Wal-Mart’s Golden Age of Accumulation: The 1960s to the Mid-1990s

Wal-Mart’s model of lean retailing took shape in its early development during the 1960s in Bentonville, in North West Arkansas. At the time, agricultural production in these rural backwaters was belatedly getting mechanized and this mechanization caused the displacement of tens of thousands of workers from the region’s farmland. Wal-Mart was thus able to draw upon surfeits of cheap, mostly female, labor. And the company wanted to keep things this way. To be sure, in Wal-Mart’s regime of labor control, patriarchy and pecuniary gain dovetail. From the company’s foundation, around 70% of its low-ranking employees have been female, yet even to this day women receive far less pay for the same work that their male counterparts carry out, and they only receive around one-third of all promotions to managerial positions (Seligman 2006, p.237). Moreover, unlike other retail giants, such as Sears, that accommodated unionization in the post-war era, Wal-Mart took a zero-tolerance approach to organized labor. It viewed, and still views, unions as an intrusion upon managerial authority and an impediment to the firm’s hallmark cost cutting strategy (Lichtenstein 2006).

Wal-Mart’s aversion to unions was manifest in the geography of its early expansion. For the first two decades of its existence, Wal-Mart built almost all of its stores in small towns in the Southeast and where organized labor has historically been weak. It largely avoided the ‘archipelago’ of union strongholds stretching from the to the metropolitan areas of , , , and (Lichtenstein 2009, p.174). The company’s focus on rural also stemmed from two other considerations. Firstly, land-use regulations were relatively loose in the Midwestern and Southeastern states. Secondly, Wal-Mart’s rivals tended to rule out non-urban communities as being too insignificant to bother with. Wal-Mart’s top managers were not beholden to this urban-bias and saw the vast swathe of near virgin retail territory in rural America as the potential outlet for irresistible growth (Holmes 2011).

However, Wal-Mart’s rural green-field growth strategy was not without its challenges. Most notably, by opening its stores in remote parts of the , Wal-Mart had difficulty securing dependable and low-cost deliveries from its suppliers (Graves 2006). Given this problem, Wal-Mart chose to develop its own distribution system and soon became renowned for being a true pioneer in ‘logistics’ – a field of knowledge which had hitherto been associated with the science of war-making. Wal-Mart did away with whole regiments of supply chain middlemen and unleashed a barrage of penalties on suppliers that did not deliver to the last letter on their contracts. Moreover, in the 1970s Wal-Mart began replacing traditional warehouses with distribution centers (DCs). Through facilitating cross-docking – a process through which merchandise is transferred directly from incoming rail cars and trucks to outgoing trucks – these DCs reduced the time that Wal-Mart held inventory from a matter of months to a matter of hours (Lichtenstein 2009). The savings from this process were considerable. By the end of the 1980s, Wal-Mart’s distribution costs were only 1.35% of sales, while the corresponding figures for rival companies Kmart and Sears were 3.5% and 5% respectively (Vance & Scott 1994, p.92).

Moreover, these DCs constituted the basis for the company’s hugely effective ‘hub and spoke’ strategy of green-field growth. This strategy entailed setting up a DC in one location and then constructing 75 to 100 stores within one day’s drive away from the DC. Once the catchment area was filled with stores, Wal-Mart would open up a new DC in an adjacent region. There were two major advantages of this strategy of differential breadth expansion. Firstly, it increased name-recognition for Wal-Mart within the areas in which it operated and thus lessened advertising costs. And secondly, it discouraged the market entry of retail rivals that belatedly recognized the commercial potential of small-town retail markets (Roberts & Berg 2012). By the end of the 1980s the company became the third largest retailer in the US, eventhough it operated in only half of the American states (Vance & Scott 1994). Thus, Wal-Mart’s method of taking control of its distribution networks proved to be a very effective way of forestalling the mimetic effects of cost cutting, on the one hand, and of accelerating its green-field growth, on the other. In the face of scant opposition, Wal-Mart was successfully threading an intricate patchwork of stores into the entire fabric of rural America.

In an attempt to increase its differential depth, Wal-Mart was one of the first discount firms to adopt Universal Product Code, or UPC, scanning. This barcode scanning technology obviated the need for retail clerks to engage in the cumbersome practice of keying in inventory data by hand and it thus enabled Wal-Mart to expedite consumer traffic at its checkouts. And by offering such an expeditious way of capturing purchasing patterns, the technology also helped curtail the informational advantage that manufacturers had in regard to consumer behavior. Moreover, Wal-Mart sought to increase its informational advantage further by launching the world’s largest private, integrated satellite network in the mid-1980s. Wal-Mart’s very own geostationary satellite, positioned some 34km above the world’s surface, transmitted all of the barcode data scanned at store checkouts to company headquarters in Bentonville. These data were then processed almost instantaneously, thus allowing Wal-Mart to speed up the reordering of store merchandise. The satellite also beamed live pep talks given by company founder, Sam Walton, to hundreds of thousands of his employees at a time, via the company’s television network (Lichtenstein 2009). And in 1990, Wal-Mart sought to build upon its existing barcode and satellite technologies, through the introduction of Retail Link – a ‘just in time’ supply system that facilitated the communication of real-time sales and in-stock data to its suppliers. Through its sophisticated infrastructure of consumer surveillance, Wal-Mart was able to further enhance the efficiency of its restocking operations, and this greater efficiency in turn helped it to attract consumers from other retailers and to invest in more store openings. Increased differential depth thus fed into increased differential breadth.

Due to this mutually reinforcing dynamic between cost cutting and green-field expansion, Wal-Mart was almost becoming a state within a state. It even had its own nomenclature. The company’s precariously employed workers were christened ‘associates’; its human resources department was termed ‘the People Division’; its founding father was known by the sentimental moniker ‘Mr. Sam’ and his multimillionaire directors were named, in true Orwellian fashion, ‘Servant Leaders’. Within this hierarchy, Sam Walton had no qualms about imbuing the firm with a cultish philosophy. In one bizarre instance of megalomania, he broadcast a video of himself to his employees enjoining them to raise their hands and repeat the following pledge: ‘[f]rom this day forward, I solemnly promise and declare that with every customer that comes within ten feet of me, I will smile, look them in the eye, and greet them, so help me Sam’ (cited in Vance & Scott 1994, p.107). Walton even invented a rallying cry for the firm – ‘the Wal-Mart Cheer’ – that its retail clerks and shelf stackers are still expected to sing with gusto at the beginning of every morning shift. As such, charismatic authority, a pseudo-communitarian spirit and the latest scientific innovations in logistics and supply-chain management, intersected to create a formidable institutional matrix for differential accumulation (Lichtenstein 2009).

However, it would be wrong to attribute Wal-Mart’s early pecuniary success solely to the corporation’s own agency. As the CasP framework suggests, we need to relate our findings back to the social hologram: the general force-field of power within which corporations operate. For one thing, the almost uninterrupted two-decade long decline of the minimum wage in the US from its zenith in 1968 was highly propitious for Wal-Mart’s expansion (Appelbaum & Lichtenstein 2006). What is more, it is worth emphasizing that these minimum wage declines took place in the context of Wal-Mart’s gendered strategy of differential accumulation. As Appelbaum and Lichtenstein explain (2006, p.24), “ecause Walton placed his stores in small communities, where rural, underemployed women were available at the minimized minimum wage, he held a striking competitive advantage over urban/suburban department stores, such as Sears and Macy’s, whose wage scales had long been structured by their effort to avoid unionization and retain a core workforce of male workers.” This differential expenses advantage was important because the retail business is very labor intensive. Supermarkets, for example, devote as much as 70% of their operating budget to labor costs (Lichtenstein 2009, p.135). Thus, Wal-Mart accrued massive benefits from keeping the wages of its predominantly female workforce in line with the sliding legal minimum.

Additionally, there was a significant shift in the balance of power away from the manufacturing sector toward the retail sector in the . Indeed, for much of the twentieth century, manufacturers used a legal device known as retail price maintenance (RPM) to control the retail prices at which their goods were sold. RPM also protected small shopkeepers from fierce price competition from larger outlets. However, when Wal-Mart was founded, RPM was already in decline, and with the passing of the 1975 Consumer Goods Pricing Act, RPM was completely outlawed. With pricing power shifting decisively in favor of large retailers, Wal-Mart was able to pursue deep discounting much more rigorously than before to the grievous detriment of small ‘mom-and-pop’ stores and manufacturers all over the country (Boyd 1997).

Moreover, the decline of manufacturing in the US coincided with the rise of global manufacturing centers abroad. Of particular importance to Wal-Mart’s expansion was the emergence of the ‘East Asian Tigers’: South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. In the 1960s and 1970s, the governments of all these countries embarked on a mixture of export-based growth, state-led proletarianization and the brutal repression of organized labor. Wal-Mart, like other major retailers in the , took note, and by 1976 it started buying merchandise directly from . And as with Wal-Mart’s retail operations in the , patriarchy and pecuniary gain meshed together in the disciplinary control of workers further up the supply chain. An estimated 90% of sweatshop workers that make garments supplied to retailers such as Wal-Mart are female. Thus, ‘the Orient’, as Sam Walton called it, and its abundance of East Asian female labor, became integral to Wal-Mart’s cost cutting regimen (Lichtenstein 2009).

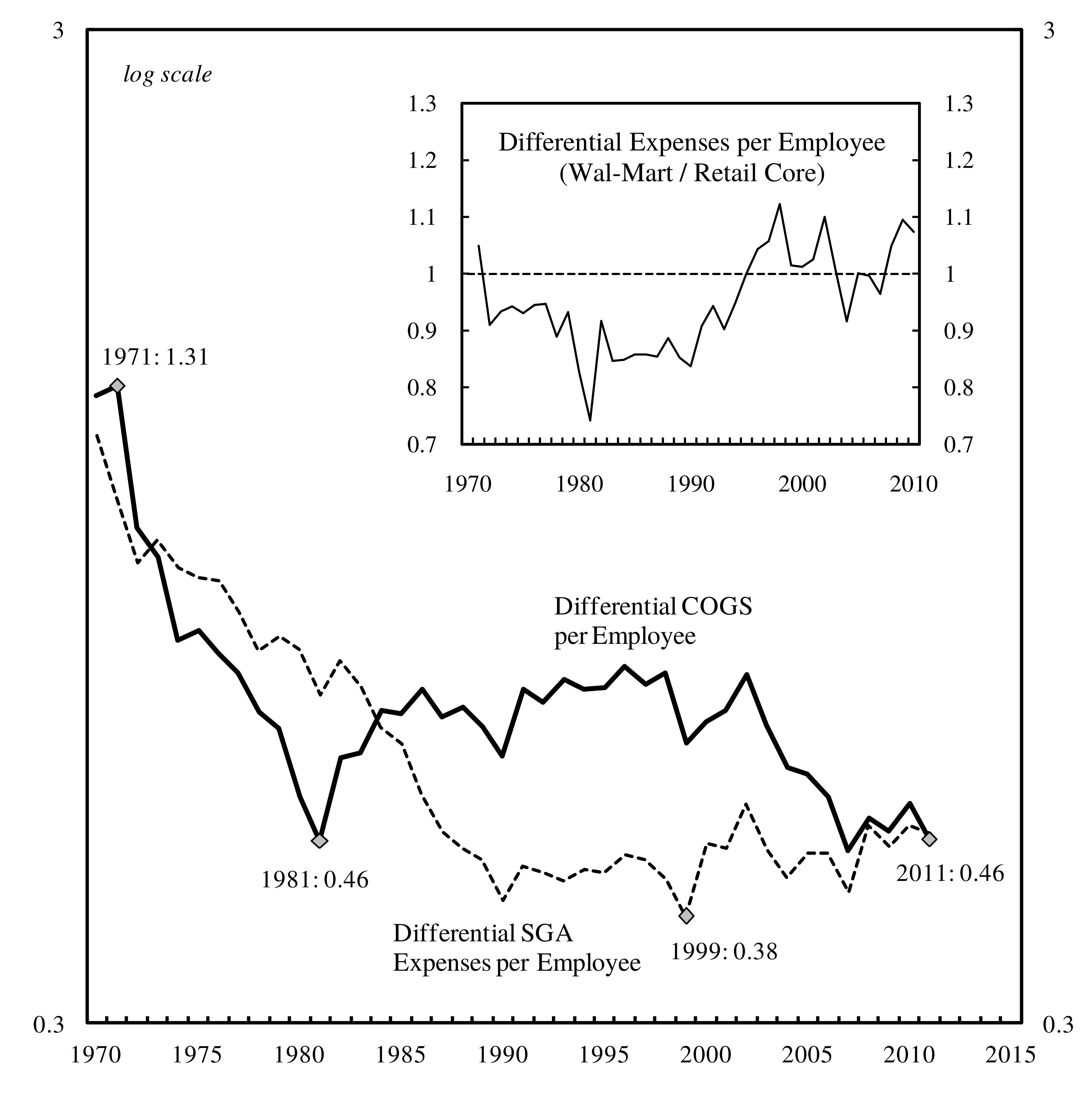

The company’s initial success in marrying its in-house logistical innovations with wage repression and supplier discipline is registered in various differential cost measures as shown in Figure 3. The main chart depicts two cost indicators: selling and general administration (SGA) expenses per employee and costs of goods sold (COGS) per employee. The first measure calibrates the efficiency of Wal-Mart’s internal operations and thus can be seen as a rough proxy of the company’s control over its workers. The second measure gages the extent to which Wal-Mart is able to project power up its supply chain so as to minimize its external costs. The data are expressed relative to the corresponding COGS and SGA expenses per employee of the average firm within the Compustat 500. In measuring Wal-Mart’s cost cutting performance in this manner we can develop a richer understanding of the differential profit and differential capitalization data presented in the previous section.

Figure 3: The Differential Cost Cutting of Wal-Mart.

Note: In the main chart, Wal-Mart’s COGS and SGA expenses per employee are expressed relative to the corresponding COGS and SGA expenses per employee of the average firm within the Compustat 500 to yield differential measures. The differential expenses measure plotted in the insert is presented as a ratio of Wal-Mart’s combined COGS and SGA expenses per employee to the Retail-Core’s combined COGS and SGA expenses per employee. The Retail-Core proxy is made up of the top 20 firms by market value listed under SIC codes 53 (General Merchandise Stores) and 54 (Food Stores) less Wal-Mart. For details of Compustat 500 see note to Figure 2.

Source: Wal-Mart, Retail-Core and Compustat 500 cost of goods sold, selling and general administration expenses and employee data from Compustat through WRDS. Series codes: COGS, XSGA and EMP.

The figure clearly shows that Wal-Mart dramatically reduced its differential COGS per employee in the 1970s. The drop in Wal-Mart’s differential SGA expenses per employee was even longer in duration and deeper in intensity, falling in the 1980s when Wal-Mart’s differential COGS had reached a plateau. Another observation one can make from Figure 3 relates to the insert positioned in the top right hand corner of the main chart. The insert combines Wal-Mart’s per employee COGS and SGA expenses and divides this number by the equivalent expenses per employee of the average firm in the Retail-Core: the top twenty largest supermarket and general merchandise firms listed in the , less Wal-Mart. As we can see, Wal-Mart’s relative costs were dropping in the 1970s and its expenses remained much lower than the average Retail-Core firm (as signified by the dotted line) for most of the 1980s. Thus, the trends until the mid-1990s testify to the early success of Wal-Mart’s logistical innovations and its disciplinary control over its workforce and suppliers. In short, the overarching power shifts in employer-employee relations, and retailer-manufacturer relations in the US and abroad, were capitalized by Wal-Mart and thereby spurred the rapid augmentation of its power.

III The Mid-1990s Onward: Wal-Mart’s Differential Accumulation Model Run into Limits

However, Wal-Mart’s differential cost cutting regimen became less effective through time. Turning back to the main chart of Figure 3, the diminished effectiveness of Wal-Mart’s cost cutting strategies is indicated by the bottoming out of Wal-Mart’s differential SGA expenses per employee ratio and the flat-lining of Wal-Mart’s differential COGS per employee ratio in the 1990s. It is also evidenced by the sudden increase since the mid-1990s in Wal-Mart’s expenses relative to the Retail-Core as presented in the insert of the figure. What explains these trends? The power theory of value suggests that one has to look at multiple social scales of resistance and restructuring to make sense of Wal-Mart’s cost cutting trajectory. Three factors appear to be of particular relevance: Wal-Mart’s declining relative logistical advance; the resistance showed by workers employed directly by Wal-Mart; and the international transformations in Wal-Mart’s supply base. While the first factor may tell us a lot about Wal-Mart’s dwindling cost cutting success relative to its retail rivals, the second factor perhaps illuminates the course taken by Wal-Mart’s differential SGA expenses per employee; and the last factor enriches our understanding of Wal-Mart’s differential COGS per employee trajectory. Let’s consider each of these factors in turn.

In regard to Wal-Mart’s declining relative logistical advance, the company is perhaps encountering the limits of the possible in terms of its differential technological innovation. Indeed, Wal-Mart has for a long time held the second largest data warehousing system in the world after the Pentagon, and by the early 2000s this system had more storage capacity than all of the fixed pages on the internet at that time (Roberts & Berg 2012). This technology has empowered Wal-Mart to gain crucial insights into the intricate shifts in the topography of consumer desire and to get its supply chains to respond accordingly. To take one example, when in 2004 Wal-Mart found out that Hurricane Ivan was heading for the Florida panhandle, Wal-Mart’s complex data-mining algorithms predicted that consumers, upon hearing news of the impending storm, would be clamoring for Kellogg’s Strawberry Pop tarts. Wal-Mart put its distribution systems on alert and stepped up the delivery of the product to its stores in Florida; and true to Wal-Mart’s prediction, sales of the strawberry flavored pastries sky-rocketed (Patel 2007). Having attained this level of logistical sophistication, it is hard to imagine how the company can develop even more advanced means of predicting, and responding to, short-term consumption trends.

Moreover, other major retailers have managed to adopt some of Wal-Mart’s innovations in supply chain management. This pattern of emulation can be seen in the fact that many major retailers have developed their own versions of Retail Link. Moreover, since the mid-2000s, Wal-Mart has gradually abandoned its traditional strategy of developing its logistical capabilities ‘in house’, and it has moved increasingly towards using third party data-gathering systems such as Terradata and Oracle Business Intelligence. Given this change in policy, it is likely that Wal-Mart is now following technological trends rather than setting them. A senior insider of the company confirmed this view of Wal-Mart’s technological capacity: ‘[w]e obviously used to be the leader, but everyone else has caught up’ (cited in Roberts & Berg 2012, p.138). This process of catch-up is clearly shown in the insert of Figure 3. For all but three of the last fifteen years, Wal-Mart’s differential expenses per employee have been higher than the average in the Retail-Core. Thus, at least in the case of Wal-Mart, Nitzan and Bichler appear entirely correct in their claim that, in the long-run, cost cutting merely enables corporations to keep up with the average, rather than surpass it. Wal-Mart’s exclusionary capacity over technologies of command and control were being replicated, and this replication in turn weighed down on Wal-Mart’s differential capitalization.

In regard to labor relations, Wal-Mart’s differential cost cutting regimen has been complicated by an ever more restive workforce. Although for much of the 1990s and 2000s Wal-Mart effectively nipped unionization efforts in the bud, lawsuits against Wal-Mart have offered a more fruitful avenue of contestation for disgruntled employees. In fact, by 2004 Wal-Mart was involved in a total of 8,000 ongoing legal cases (Olive 2004). The cases were launched in regard to a panoply of complaints concerning gender discrimination, violation of state and federal regulations on overtime, lunch breaks and health and safety. The most famous of these was the ‘Duke versus Wal-Mart’ case – the largest class action attempt in history, involving 1.6 million female plaintiffs who were allegedly discriminated against when working for Wal-Mart. The Bentonville giant successfully appealed to the US Supreme Court to revoke the class action status of these legal efforts and, in so doing, the company saved itself from the possibility of paying billions of dollars in damages. However, Wal-Mart has not been able to avoid all of the legal repercussions of its draconian labor practices. To illustrate, in 2008 alone Wal-Mart agreed to pay as much as $640 million to settle 63 suits across the US over charges that it did not provide its employees with meal breaks and proper rest (Banjo 2012; Reuters 2012; Seligman 2006).

Additionally, there has been a recent upsurge in struggles waged against Wal-Mart outside of the law courts. Indeed, in October 2012, over 70 Wal-Mart retail clerks engaged in walkouts in Los Angeles. Shortly after, the walkouts spread to 28 Wal-Mart stores in 12 different states. The strike represented the most sustained and extensive labor offensive against Wal-Mart in the company’s history. The actions were taken because Wal-Mart allegedly harassed and cut the hours of workers who became affiliated to OUR Wal-Mart (Organization United for Respect at Wal-Mart) – a nonunion campaign group that seeks better pay, more affordable health care and improved working conditions for Wal-Mart employees. One year later, in 2013, OUR Wal-Mart spearheaded protests of a similar magnitude. The growing resistance, manifest most clearly on the picket line and in the law courts, may have contributed to the slight uptrend in Wal-Mart’s differential SGA expenses per employee since the turn of the millennium.

The data for Wal-Mart’s differential cost of goods sold per employee, as displayed in Figure 3, have a more complex trajectory. After an upward bump in its relative cost of goods sold in the early 1980s, Wal-Mart’s external expenses flat-lined for the rest of the 1980s and for much of the 1990s. Then in 2002 Wal-Mart’s differential COGS per employee started falling. And in 2007, it almost reached the historic low that Wal-Mart attained in the early 1980s, only then to rise again somewhat thereafter. As indicated above, in order to better comprehend these quantitative changes in Wal-Mart’s relative expenses it may be worthwhile considering the contested restructuring of Wal-Mart’s supply chain.

In the mid-1980s, Wal-Mart’s supply base in ‘the Orient’ shifted away from the East Asian Tiger countries toward China. This shift was caused by a number of factors: rising wages and a more politically assertive working class in and ; the reflation of most East Asian currencies as negotiated in the 1985 Plaza Accords; and the market-based transformation of the Chinese political economy onto an export-orientated platform under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. Since that point, many of Wal-Mart’s suppliers have relocated their operations in the coastal regions of . Partly as a result, by the late 2000s, over 80% of Wal-Mart’s registered suppliers were located in China (Gereffi & Christian 2009, p.579). Wal-Mart’s interests are in a number of respects now concordant with the interests of the Chinese ruling elite: both have a common concern with the maintenance of labor discipline, social stability and a devalued renminbi so as to make exported goods from China as cheap as possible.

The sharp fall in Wal-Mart’s differential COGS per employee between 2002 and 2007 may in part be due to ’s accession to the WTO in 2001. Indeed, the ensuing trade liberalization made Chinese firms much more exposed to international competition which in turn compelled them to cut costs further. Wal-Mart appeared to reap the rewards of this cost cutting and ramped up its sourcing drive in . In fact, between 2001 and 2006 the company’s orders constituted around 11% of the growth of America’s trade deficit with China (Scott 2007). However, many Chinese manufacturers now appear to be squeezed by Wal-Mart to the very limit. For Wal-Mart’s suppliers to retain their wafer thin profit margins, they will have to shift the burden of cost cutting further onto their employees who are already working in immensely harsh conditions. As such, further differential cost cutting through this avenue is likely to be more difficult than before.

As mentioned above, since 2007 we can see that Wal-Mart’s differential cost of goods sold per employee have risen somewhat. This slight uptrend may partly be the result of the exhaustion of the one-shot effect of the trade liberalization inaugurated by ’s accession to the WTO. The gradual reflation of the Chinese renminbi against the US dollar since 2010 may have also played a role in the levelling of Wal-Mart’s differential COGS per employee. Although this gradual reflation may be welcomed by elements of the US government that have accused the CCP of ‘currency manipulation’, it has probably had a negative impact on Wal-Mart’s relative external expenses, as it has made Chinese exports more costly.

But perhaps more fundamentally, the slight increase in Wal-Mart’s relative external expenses may be the result of the increased difficulty that the Chinese government has had in maintaining the obedience of Chinese workers in recent years. On a general level, the recent capitalist transformation of China has caused huge social dislocations within the country, and it has contributed to rising disaffection amongst the Chinese population. This rising disaffection is registered in the thirteen-fold increase in labor disputes in the country between 1995 and 2006. These labor disputes have often spilled over into what the Chinese police apparatus calls ‘mass incidents’. According to Chinese government statistics, these public disturbances – which can range from riots to demonstrations to group protests and strikes – have also increased dramatically. In 1994, there were 10,000 mass incidents involving 730,000 participants; by 2005, there was 84,000 such disturbances involving over 4 million people (Keidel 2006, 2). Although the accuracy of these figures may be questioned, there is little reason to doubt the general uptrend in unrest that they indicate. In response to the increasingly febrile conditions in , the CCP has sought to mollify Chinese citizens by passing a raft of measures. The Labor Contract Law of 2008 epitomized its mitigation efforts. This law has strengthened the rights of employees and in so doing it has increased the production expenses and legal liabilities of employers (Chan 2011).

As a result of these changes, many of Wal-Mart’s suppliers have sought to relocate their operations in countries where labor costs are lower. This shift in emphasis was hinted at in Wal-Mart’s announcement in 2010 that it would double its purchase of textiles made in Bangladesh and that 20% of its garment shipments would be sourced from that country (Chan 2011). has a minimum wage of $37 per month – the lowest in the world; and it also has the dubious distinction of having incredibly weak manufacturing regulations. The cost cutting measures Wal-Mart demands from its suppliers, coupled with the loose government regulations, can make working conditions in many of the textile factories very hazardous. In fact, in late 2012, a major fire in a cramped garment factory in the suburbs of killed 112 workers. Five of the 14 production lines in the factory were devoted to making clothing sold exclusively in Wal-Mart stores (Greenhouse & Yardly 2012). Soon after the factory inferno it was revealed that in 2011 Wal-Mart, along with Gap, had blocked measures proposed by Bangladeshi government officials and labor leaders in a key conference regarding fire safety. The Wal-Mart representative in the meeting reportedly demurred that the proposed fire safety improvements would entail “very extensive and costly modification” and that it was “not financially feasible… to make such investments” (cited in Greenhouse & Yardly 2012). The ultimate price for Wal-Mart’s financial feasibility concerns was paid by those garment workers who died of asphyxiation and first-degree burns. The site of the smoldering factory was thus the true Ground Zero of Wal-Mart’s global cost cutting strategy.

Such are the social limits of Wal-Mart’s stuttering cost cutting regimen, but what about the social limits to the company’s other major route to power augmentation: green-field investment? By the late-1980s much of rural was integrated by Wal-Mart’s retail operations. And by the early 1990s Wal-Mart had come to dominate the discount sector along with its two major rivals – Kmart and Sears. As such, there was little room for Wal-Mart’s continued expansion within its existing pecuniary ambit, both in sectoral and geographical terms. Wal-Mart began to extend its business interests from rural to metropolitan areas; and from non-food retailing to food retailing. However, by extending its dominion in this manner, Wal-Mart was impinging on the territorial domains of its rivals. Moreover, by entering the union strongholds in the Northeast and the West Coast, it was also setting itself on a collision course with organized labor. In this respect, the specter of labor resistance did not just haunt Wal-Mart’s cost cutting strategies, but also its green-field growth ambitions (Lichtenstein 2009; Roberts & Berg 2012).

Wal-Mart’s move into groceries and city-spaces catalyzed a breathtaking wave of consolidation in the retailing sector. In the years between 1992 and 2003, 13,000 traditional supermarkets closed down and at least 25 regional grocery chains were driven into bankruptcy (Lichtenstein 2009, p.135). And as a defensive response to Wal-Mart’s seemingly irresistible expansion, the largest supermarkets in the engaged in a wave of mega-mergers in the late 1990s. In 1994 it took 20 of the largest US food retailers to account for 40% of sector-wide sales; but by 1999 it took just five supermarket chains to attain the same percentage (Milling & Baking News 1999, p.12).

Notwithstanding this consolidation amongst rival retailers, Wal-Mart’s sectoral expansion into food retailing and its geographical expansion into metropolitan areas has been a triumph. By 2001, Wal-Mart attained the largest share of sales in the grocery sector in the US. And astonishingly, by 2009, 96% of the US population now lives within 20 miles of a Wal-Mart store and 60% lives within 5 miles (Zook & Graham 2009, p.20). However, the company has in certain respects become a victim of its own success because in some areas of the new stores have begun to take business away from its existing stores. The company estimated in its 2004 Annual Report that existing stores lost 1% in revenues from ‘self-cannibalization’ (Wal-Mart 2004). This process cannot be understood without reference to the resistance of its customers to exceeding a certain level of consumption. As such, market saturation should not be understood merely as an economic category, but rather as a social limit on corporate power.

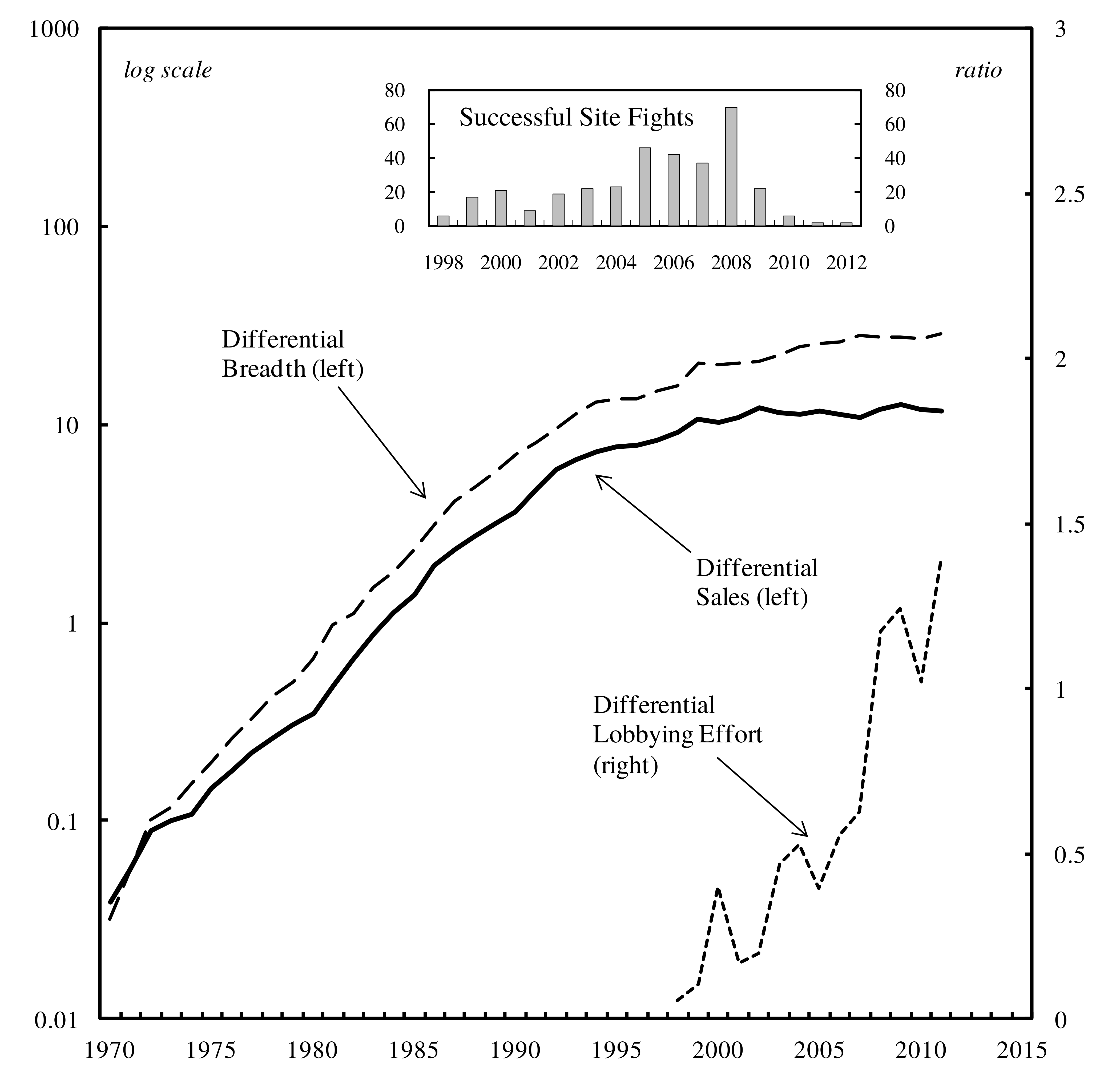

Yet this kind of resistance to Wal-Mart’s green-field growth is inherently passive and latent: it is constituted by what consumers are not doing to boost Wal-Mart’s expansion, rather than what they are doing to stymie it. Yet just as there has been active resistance that has directly scuppered Wal-Mart’s cost cutting strategies as detailed above, there has also been active resistance that has directly targeted Wal-Mart’s green-field expansion. To be sure, Bernstein Research, the Wall Street-based investor advisory firm, produced a report in 2005 warning shareholders that Wal-Mart’s growth “is under siege in several regions of the country from growing opposition by local communities.” The report concluded that the “heightened resistance” could slow down the company’s square footage growth rates, which in turn could negatively impact Wal-Mart’s stock price and earnings per share (cited by Norman 2007). Community resistance has been most pronounced in the ‘site fights’ headed by local activists and labor unions who have sought to lobby local and municipal governments to change zoning and land-use laws so as to thwart Wal-Mart’s planned store openings. When viewed on a case-by-case basis, these grassroots mobilizations can be derided as exhibiting little more than ‘not-in-my-back-yard’ parochialism. However, when considered on a nationwide level these local struggles appear to be part of a sustained and expansive movement of resistance against Wal-Mart. As shown in Figure 4, the site fight phenomenon climaxed in 2008, when 70 of Wal-Mart’s planned store openings were blocked or postponed. Given the fact that the average Wal-Mart store makes over $50 million in annual sales (author’s own calculations), each community victory represents a considerable blow to the company.

Figure 4: Wal-Mart’s Encumbered Expansion.

Note: Differential lobbying effort is calculated by dividing Wal-Mart’s annual lobbying expenditure by the estimated lobbying expenditure of the average firm in the Compustat 500. The estimated lobbying expenditure of the average firm in the Compustat 500 is based on the not unreasonable assumption that the 500 largest firms account for 85% of total lobbying expenditure in the US. This proportion is then multiplied by total lobbying expenditure, which encompasses the amount spent by corporations, labor unions and other organizations to lobby Congress and other federal agencies, and divided by 500. Wal-Mart’s differential breadth and differential sales are calculated by dividing the employees and sales figures for Wal-Mart by the respective employees and sales figures for the average firm in the Compustat 500. Successful site fights are defined as those grassroots struggles that successfully block or postpone the opening up of one or more Wal-Mart stores in any one area in the US, through litigation battles and/or the canvassing of support in local government.

Source: Lobbying expenditure data from Center for Responsive Politics, http://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?id=D000000367&year=2012 [accessed 9 September 2012). Wal-Mart and Compustat 500 employee and sales data from Compustat through WRDS. Series code: REVT and EMP. Site fight data collected from Al Norman database https://sprawl-busters.com/victories/, [accessed 9 September 2012].

Partly in response to the intensified resistance, Wal-Mart revised its domestic expansion target in 2007 from 265-70 new supercenter openings per year down to 170 for the three following years (Norman 2007). But, despite their being fewer new targets for community activists, site fights still rage on. At the time of writing, Wal-Mart was going through a protracted battle over plans to open a new store in Los Angeles’ historic Chinatown. In late June 2012, thousands of Angelinos – ranging from union organizers to Chinese owners of small ‘mom-and-pop’ shops – joined together in the largest anti-Wal-Mart march to date, to express their opposition to the slated store opening. As a result, active resistance to Wal-Mart’s green-field growth in some areas of the US has exacerbated the problems of market saturation in other areas of the country.

The site fights and legal battles against Wal-Mart have drawn attention to the company’s harsh labor conditions, low-pay and baleful impacts on many small business and communities. Wal-Mart’s public image deteriorated during the 2000s, and this deterioration in turn began to undermine the company’s sales. The management consultants, McKinsey & Company, estimated that up to 8% of Wal-Mart’s customers had stopped shopping in Wal-Mart stores because of the negative coverage the retail colossus received (Birger 2007). The unflattering press has clearly increased the company’s ‘reputational risk’ as consumers have increasingly adopted a passive aggressive posture towards the corporation. This contention is corroborated by the quantitative evidence presented in the main chart of Figure 4. The chart shows how Wal-Mart’s differential sales – the ratio of Wal-Mart’s revenues to the revenues of the average firm in the Compustat 500 – began to grow at a slower pace in the 1990s and then plateaued in the 2000s. Moreover, the chart shows that Wal-Mart’s differential breadth, measured as the ratio between the number of Wal-Mart employees and the employment of an average Compustat 500 firm, has also flattened off dramatically over the last twenty years. Taken together these data suggest that Wal-Mart’s expansion has become increasingly encumbered by resistance.

The end of our power analysis is in sight, but it is worth making one final point before we conclude. Sam Walton is dead. His name is still reverentially invoked by Wal-Mart executives in the company’s annual shareholder extravaganzas some twenty-two years after his passing. “What would Sam do?” they ask. “Wouldn’t Sam be proud?” they beam. But the charismatic authority associated with the leader died along with him. Wal-Mart can no longer pass off as a folksy upstart business in the rural backwaters of the US. And its restive workers can no longer be dismissed as merely recalcitrant underlings in a seemingly benign family-cum-corporation. Wal-Mart is, in fact, now thoroughly enmeshed in the bureaucratic authority of the US government as a whole. A government-relations unit was established in 1999, and as Figure 4 shows, Wal-Mart began to dramatically increase its differential lobbying effort – a measure that compares the company’s lobbying expenditure to the estimated lobbying expenditure of the average firm within the Compustat 500. At the federal level, Wal-Mart has sought to put greater pressure on government to lower trade barriers against countries from which the company wants to import more goods. At the state level, Wal-Mart has increasingly lobbied for changes in benefits and wage laws. And at the level of local government, Wal-Mart has ever more earnestly sought to gain the favor of municipal politicians in its attempts to combat community activists opposed to its slated store openings (Basker 2007). Thus, as the company has got larger and larger and more and more entwined with the structures of government, the struggle within and against Wal-Mart has increasingly assumed the form of a struggle over organized power at large. Like almost all other revolutions then, Walton’s ‘retail revolution’ is ossifying in the face of discontent.

IV The Future of Wal-Mart and the Future of Corporate Power

This article has sought to advance a power theory of value approach to Wal-Mart’s contested expansion and in so doing it has pointed to methodological tools that may help researchers carry out political-economic research on the trajectories of other major corporations. As I have argued, Wal-Mart’s initial pecuniary success owes to a combination of external breadth (green-field investment) and internal depth (cost cutting). This strategy depended on a reinvestment regime of logistical innovation, ceaseless store openings and rigid control over predominantly female workers throughout its supply chain.

In terms of breadth, Wal-Mart largely grew ‘under the radar’ of retail rivals and organized labor in the first two decades of its existence. It expanded at a dramatic pace in the relatively un-stored, un-regulated, un-unionized and uncontested retail landscape of the Southeast and Midwest. But it was harder for the company to apply its distinct model of retailing to the metropolitan areas of the Northeast and Far West, where unions have traditionally been most active, where municipal zoning rules have been more heavily contested and where its major retail competitors have been strongest. Soon after Wal-Mart moved into these areas it became subject to increased resistance. Thus, by virtue of its sheer size and prominence in the US retail sector, Wal-Mart became a company that could not be ignored. Its green-field growth strategy in the US became encumbered by contestation and its brand became sullied by its association with low pay, poor labor conditions and discriminatory practices against its female employees. Despite Wal-Mart’s recent attempts at greening its image, persisting ‘reputational risk’ continues to undermine investors’ confidence in the firm’s capacity to draw more socially conscious consumers within its stores.

In terms of depth, the company’s cost cutting measures have also been undermined by resistance through time. Wal-Mart managed to make deep differential cuts into its operating and inventory costs during its golden age of rapid growth. It was at the forefront in the advancement of new logistical technologies and thus quickly surpassed its rivals in the field of supply chain management. Moreover, although it was not the first major retailer to source goods from East Asia, by the 1990s it had the largest network of suppliers in the region. Wal-Mart’s suppliers filled their sweatshops with masses of underpaid female workers who had migrated from rural areas of Southeast Asia, just as Wal-Mart had initially filled its own stores with underpaid female retail clerks who were sidelined by agrarian transformation in Southeast and Midwest US. The differential success of this explicitly gendered nexus of corporate power is undeniable. Perhaps no other organization in history has capitalized the energies of feminized, and broadly racialized, labor more effectively and on such a colossal scale.

However, Wal-Mart’s supply chain supremacy has been eroded. This erosion has partly been caused by the spread of logistical innovations, first appropriated by Wal-Mart, across the retail sector. It has also been caused by opposition to Wal-Mart’s model of lean retailing at all levels of its supply chain: from its workers involved in the OUR Wal-Mart campaign; from its suppliers whose wafer thin margins can hardly be rendered any thinner; and from the suppliers’ employees, some of whom are literally engaged in a life and death struggle over the conditions within which they work. As such, the differential advantage Wal-Mart has attained through cost cutting has been circumvented over time by the process of business replication and the absolute gains Wal-Mart has made from cost cutting may run into limits imposed by social resistance.

Wal-Mart has sought to offset both the latent and direct resistance it has experienced by expanding its retail operations abroad. An assessment of these retail operations is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it is worth nothing that Wal-Mart only began to colonize foreign retail markets in the mid-1990s, when its growth in the US retail market was showing signs of slowing down. To borrow the phrase of Nitzan and Bichler, Wal-Mart was ‘running out of breadth’ in the US and therefore sought new outlets for growth (2009, p.390). Yet in 2014, Wal-Mart’s foreign retail operations are expected to account for 28% of Wal-Mart’s total sales and only 19% of its profits (The Economist 2014). These are admittedly imperfect indications of the extent of Wal-Mart’s internationalization given the vicissitudes of international exchange rates and transfer pricing. Nonetheless, the gap between the share of total sales and the share of total operating income held by Wal-Mart’s international division suggests that the company’s US business continues to be more profitable than its retail operations abroad.

Moreover, as the data in Figures 2 and 4 suggest, the internationalization has failed to reverse the slowing growth in its relative employee numbers or its differential capitalization. In fact, in 2012 Wal-Mart announced that it would cut store openings for its international division by an astonishing 30% (Jopson 2012). The massive downsizing of expansion plans was motivated by the desire to attain satisfactory levels of profitability and assuage outstanding bribery claims made against the company. Bribery allegations first broke out after revelations that Wal-Mart was greasing hands in Mexico to expedite zoning approvals for store openings, but it now encompasses alleged breaches in US anti-corruption laws in its nascent operations in India. With opportunities for frictionless growth characteristic of the first few decades of its existence now long gone, Wal-Mart appears to be pushing the limits of legality in its bid to expand further (Barstow 2012).

To conclude, the prospects of Wal-Mart experiencing another golden age of rapid growth look very dim. Wal-Mart’s differential capitalization has not risen in a sustained fashion for the last two decades. This finding suggests that investors remain agnostic about the company’s capacity to greatly increase its earnings relative to dominant capital as a whole in the future. This agnosticism appears to be partly born out of an awareness of the opposition, both passive and active, that Wal-Mart is encountering at multiple social scales. The corporation presently has a 2% share of the total capitalization, and thus overall power, of the top 500 firms listed in the US. However, with Wal-Mart’s green-field growth running into barriers and with its cost cutting measures approaching a floor, it does not seem likely that the company will be able to increase its relative pecuniary earnings further. Moreover, as four of the top ten richest people in the US are members of the Walton family, and as hundreds of thousands of ‘associates’ are struggling to get by on poverty wages, the company might get increasingly drawn into the wider debates about inequality that were brought to the fore by the 2011-12 Occupy Movement. In this respect, Wal-Mart’s evolution does not just concern the trajectory of just one company; it points to the asymptotes of business power as a whole. But for those seeking a more just and humane social order, undermining dominant firms’ confidence in obedience is necessary but not sufficient. The key challenge is to forge a new way of organizing and accounting for social reproduction that breaks with the power logic of capitalization.

Notes

The impetus for this research project was sparked by a post by D.T. Cochrane entitled ‘Wal-Mart: Stagnant Since 1999’ on the forum page of https://capitalaspower.com. I am very grateful to D.T. Cochrane and Jonathan Nitzan for their invaluable support at every stage of the research and writing of this article. Thanks are also due to Donya Ziaee, Sandy Brian Hager, Sune Sandbeck and the two anonymous reviewers. I gratefully acknowledge Ontario’s Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities for awarding me an Ontario Graduate Scholarship in support of my research. Finally, it should be noted that this article builds upon research I presented in a chapter that I wrote for The Handbook of International Political Economy. More specifically, the current piece leverages the findings presented in the handbook to generate new arguments and insights. Importantly, whereas the chapter in the handbook focuses specifically on labor resistance to Wal-Mart’s international retail expansion, this article addresses the multiplicity of factors limiting Wal-Mart’s growth in the US. The usual disclaimers apply.

-

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Baud and Durand’s article concerns its supplemental analysis of the ‘distributed value to shareholders’ — defined as the percentage of a corporation’s net income and net interest committed to shareholder dividend payments and stock buybacks. This measure has increased for Wal-Mart from just over 10% in the early 1990s to almost 60% in the mid-2000s. Although an analysis of such a significant percentage rise lies beyond the purview of this article, the putative ‘shareholder value revolution’ requires urgent attention from scholars engaged with the capital as power framework. More specifically, I submit that there needs to be research on whether the apparent increase in the redistribution of dominant capital’s income from banks to shareholders, through dividends and stock buybacks, has led to a transformation in the strategies adopted by major corporations to augment their differential capitalization.↩

-

For an analysis of banking firms that is informed by the power theory of value, see Hager, S.B. (2012) Investment Bank Power and Neoliberal Regulation: From the Volcker Shock to the Volcker Rule, in Overbeek, H. & van Apeldoorn, B., (eds.), Neoliberalism in Crisis. Basingstoke, UK. Palgrave Macmillan. Other important analyses drawing on the capital as power framework in recent years include:

- Brennan, J. (2013) ‘The Power Underpinnings, and Some Distributional Consequences, of Trade and Investment Liberalisation in Canada’, New Political Economy, 18(3), pp.715-747

- DiMuzio, T. (2012) ‘Capitalizing a Future Unsustainable: Finance, Energy and the Fate of Market Civilization,’ Review of International Political Economy, 19(3), pp. 363–388;

- Hager, S.B., (2013) What Happened to the Bondholding Class? Public Debt, Power and the Top One Per Cent, New Political Economy, DOI: 10.1080/13563467.2013.768613, pp.1-28

- McMahon, J. (2013) ‘The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema’, Review of Capital as Power, 1(1), pp.23-40

- Bichler, S. & Nitzan, J. (2014) ‘No Way Out: Crime, Punishment and the Capitalization of Power’, Crime, Law and Social Change, DOI: 10.1007/s10611-013-9505-3, 1-22.

References

Appelbaum, R. & Lichtenstein, N. (2006). A New World of Retail Supremacy: Supply Chains and Workers’ Chains in the Age of Wal-Mart. International Labor and Working-Class History. 70(1): 106-25.

Aoyama, Y. (2007). Oligopoly and the Structural Paradox of Retail TNCs: An Assessment of Carrefour and Wal-Mart in . Journal of Economic Geography, (7): 471-90.

Baines, J. (2014). Food Price Inflation as Redistribution: Towards a New Analysis of Corporate Power in the World Food System. New Political Economy. 19(1): 79-112.

Banjo, S. (2012). Wal-Mart to Pay $4.8 Million in Back Wages, Damages. Wall Street Journal. Online edition. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304868004577378381606731206.html (accessed 22 September 2012).

, D. (2012). Vast Mexico Bribery Case Hushed Up by Wal-Mart after Top-Level Struggle, New York Times. Online edition. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/business/at-wal-mart-in-mexico-a-bribe-inquiry-silenced.html?pagewanted=all&-moc.semityn (accessed 23 September 2012).

Basker, E. (2007). The Causes and Consequences of Wal-Mart’s Growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3): 177-198.

Baud, C. & Durand, B. (2012). Financialization, Globalization and the Making of Profits by Leading Retailers. Socio-Economic Review. (10): 241-66.

Bianco, A. (2006).The Bully of Bentonville: How the High Cost of Wal-Mart’s Everyday Low Prices is Hurting America. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Bichler, S. & Nitzan, J. (2014) ‘No Way Out: Crime, Punishment and the Capitalization of Power’, Crime, Law and Social Change, DOI: 10.1007/s10611-013-9505-3, 1-22.

Birger, J. (2007). The Unending Woes of Lee Scott. Fortune. Online edition. 9 January 2007. https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2007/01/22/8397972/index.htm (accessed 22 September 2012).

Bonacich, E. with Hardie, K. (2006). Wal-Mart and the Logistics Revolution. In N. Lichtenstein (Ed.) Wal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First Century Capitalism, (pp.143-162). New York: The New Press.

Boyd, D.W. (1997). From "Mom and Pop" to Wal-Mart: The Impact of the Consumer Goods Pricing Act of 1975 on the Retail Sector in the . Journal of Economic Issues, 31(1): 223-32.

Brennan, J. (2013) ‘The Power Underpinnings, and Some Distributional Consequences, of Trade and Investment Liberalisation in Canada’, New Political Economy, 18(3): 715-47.

Center for Responsive Politics, (2013). Wal-Mart Lobbying Profile, http://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?id=D000000367&year=2012 (accessed 24 March 2013)

Chan, A. (2011). Introduction: When the World’s Largest Company Encounters the World’s Biggest Country. In A. Chan (Ed), Wal-Mart in China, Ithaca, (pp.1-9), Cornell University Press. Ithaca: ILR Press.

Christopherson, S. (2007) Barriers to ‘US style’ lean retailing: the case of Wal-Mart’s failure in Germany, Journal of Economic Geography. (7):451–69.

Cummings, J. (2004). Wal-Mart Opens for Business in a Tough Market: Washington, The Wall Street Journal, March 24, 2004: A1.

Durand, C. & Wrigley, N. (2009) Institutional and Economic Determinants of Transnational Retailer Expansion and Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Wal-Mart and Carrefour, Environment and Planning A, (41): 1534-55.

DiMuzio, T. (2012) ‘Capitalizing a Future Unsustainable: Finance, Energy and the Fate of Market Civilization,’ Review of International Political Economy, 19(3): 363–88.

Eidelson, J. (2013) Tens of Thousands Protest, Over 100 Arrested in Black Friday Challenge to Wal-Mart, Alternet. November 30, 2013, http://www.alternet.org/activism/tens-thousands-protest-over-100-arrested-black-friday-challenge-wal-mart (accessed 2 February 2014).

Gara, T. (2013). Wal-Mart’s Big Challenge in Three Charts. Wall Street Journal Online Blog. November 25, 2013. http://blogs.wsj.com/corporate-intelligence/2013/11/25/wal-marts-big-challenge-in-three-charts/ (accessed 2 February 2014).

Gereffi, G. & Christian, M. (2009). The Impacts of Wal-Mart: The Rise and Consequences of the World’s Largest Retailer. The Annual Review of Sociology (35), 573-591.

Gereffi, G. and Korzeniewicz, M. (eds) (1994). Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism : Greenwood Publishing Group.

Gibbon, P., Bair, J. and Ponte, S. (2008), ‘Governing Global Value Chains: An Introduction’, Economy and Society, 37 (3): 315–38.

Graves, W. (2006). Discounting Northern Capital: Financing the World’s Largest Retailer from the Periphery. In ed. S. Brunn (Ed), Wal-Mart World, (pp.47-54). : Routledge.

Greenhouse, S. & Yardley, J. (2012). As Wal-Mart Makes Safety Vows, It’s Seen as Obstacle to Change, New York Times, December 28, 2012: A1.

Hager, S.B. (2012) Investment Bank Power and Neoliberal Regulation: From the Volcker Shock to the Volcker Rule, in Overbeek, H. & van Apeldoorn, B., (eds.), Neoliberalism in Crisis. Basingstoke, UK. Palgrave Macmillan.