Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Thank you Scot.

First, I had always understood that the Fed’s love affair with monetarism died with Volcker’s failed monetarist experiment in the 1980s, that the Fed thereafter returned to targeting the Fed Funds Rate instead of trying to actively manage debt and monetary aggregates.

I think it is useful to distinguish monetarism from its policy instruments. Interest rates and the so-called money supply (an umbrella term that can mean many different things) are often used as policy instruments. They are also related, insofar as changing one alters the other, and vice versa. Central bankers and economists bicker constantly on the proper way to calibrate these slippery variables.

That being said, theoretically, most central bankers and mainstream economists agree that inflation is a monetary phenomenon in the sense that P = M * V / Q, and then argue endlessly on the meaning of each variable and how they lag each other in time. (When I came to work at the Bank Credit Analyst Research Group in the 1990s, I presented some of my PhD work on ‘Inflation as Restructuring’. One of the lead editors told me that although he found my argument fascinating, in the final analysis in didn’t matter: when all was said and done, inflation was all about the growth of money.)

what the Fed publishes (and the IMF appears to use) as the US monetary base (the series BOGMBASE) is not “the overall value of notes and coins circulating in each country/area” but rather the “currency in circulation” plus “reserve balances,” which by definition do not circulate.

Yes, you are correct; my definition was inaccurate. But the distinction between currency in circulation and reserve balances is mostly a technical feature that facilitates settlements among private banks and between private banks and the central bank. The key thing is that the monetary base is the only money aggregate that central banks control directly. The other aggregates (M1, M2, etc.) are determined jointly with the private sector.

The end of monetarism

A note by Shimshon Bichler & Jonathan Nitzan

According to Milton Friedman, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon of too much money chasing too few commodities. Following this logic, the Holy Grail of neoliberal policy is to have the so-called money supply expand just a bit faster than the long-term growth trend of the ‘real economy’. This way, the economy is given some flexibility — but not enough to stoke the monetarist fire of inflation.

And sure enough, as our chart shows, central bankers in the advanced capitalist economies — the U.S., Europe and Japan — adhered to the spirit of this policy up until the early 2000.

The chart plots the size of the ‘monetary base’ — namely, the overall value of notes and coins circulating in each country/area. This value is expressed in local currency and is rebased with January 2008 = 1 to enable temporal comparisons between the different series.

Until the beginning of the new millennium, the monetary base grew gradually and predictably, just as monetarism demanded. But in the early 2000s, the orthodoxy started to rattle. The first deviant was the Bank of Japan, whose ‘quantitative easing’ aimed — or so we were told — to fight the country’s persistent deflation. And then came the 2008 global financial crisis and all hell broke loose.

Having panicked, ‘policymakers’ started issuing high-power money as if there was no tomorrow. Initially, they justified their heresy by end-of-the-world scenarios of financial collapse. But while the danger came and went, their quantitative easing stayed. Since 2008, the monetary base of the EU rose 7.2 times, Japan’s 7.3 times, and the U.S.’s 8.3 times.

Adding insult to injury, this historically unprecedented breakdown of monetarist policy was accompanied by an equally radical refutation of monetarist theory. Recall that monetarism claims that money growth fuels inflation — yet despite the monetary explosion, inflation refused to cooperate. From 2008 to 2020, consumer prices rose by only 29% in the U.S, 17% in the EU and a mere 3% in Japan.

For more: see ‘Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Three Views on Economic Policy in Times of Crisis’.

… is there a specific event that we should consider as the key trigger? Doesn’t this all coincide with the end of Bretton Woods?

I don’t know about triggers, events and Bretton Woods.

From a CasP viewpoint, the reason seems straightforward.

Neoliberalism is the rule of dominant capital; this rule is based on the hierarchical growth of dominant capital; this hierarchical growth amplifies the extent and intensity of strategic sabotage; and in order to avoid systemic implosion, this sabotage must be offset to some extent. That is why neoliberal governments become bigger, the deficits get amplified and their debts soar.

For a recent account of this process, see Dominant Capital and the Government.

Is the small “dead cat bounce” of 2021 (if I’m not mistaken) due to the general Covid-related recovery plans issued in OECD countries?

Could be.

The neoliberal debt balloon: since 1980, the economy grew freer and freer while the OECD government debt/GDP ratio inflated. By 2021, this ratio was three times larger than it was in 1980.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

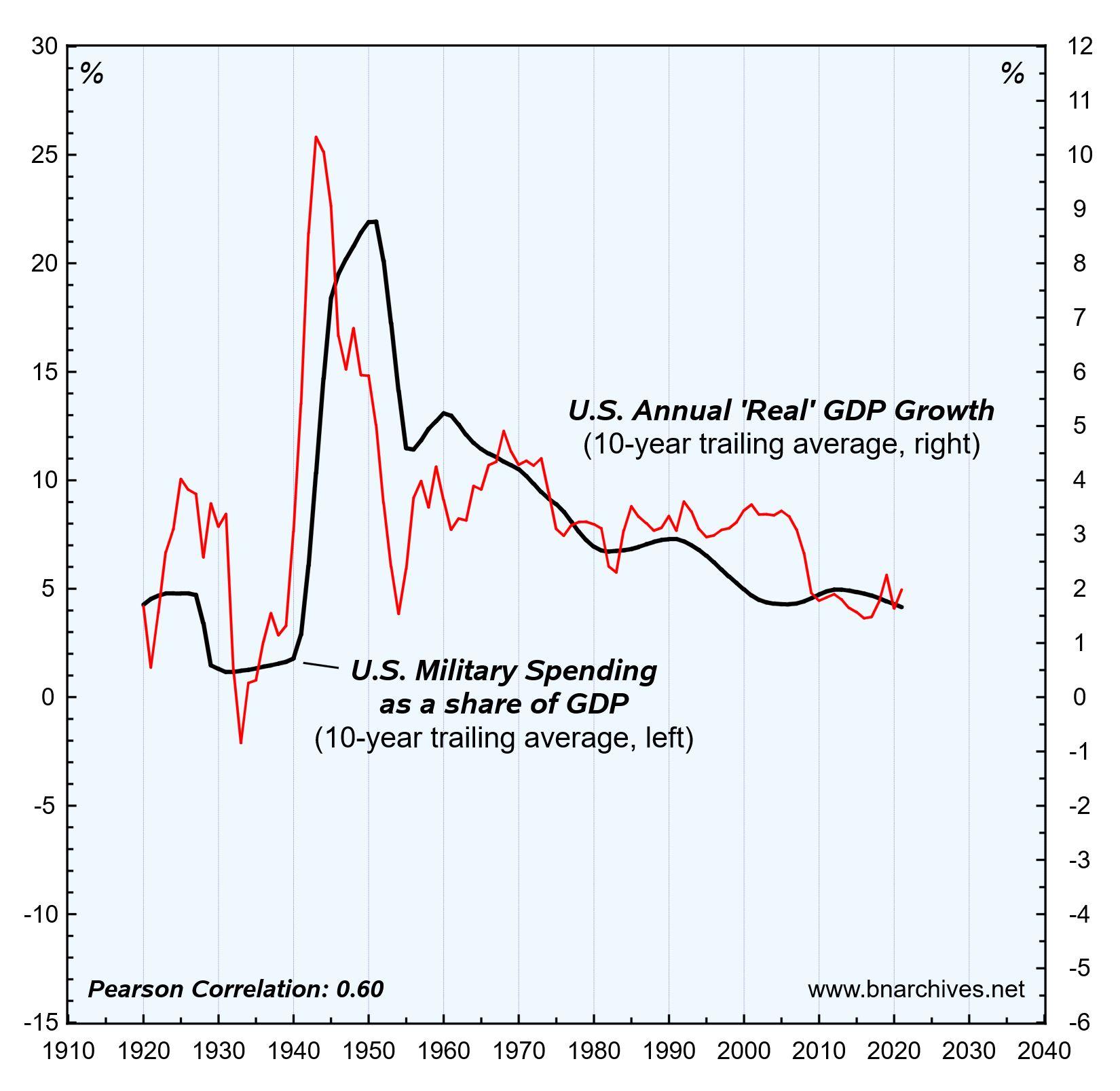

January 25, 2022 at 12:28 pm in reply to: Military Spending and Economic Growth in the United States #247621The reason for displaying the military spending series on a log scale is that it makes correlation visually clearer. Here is what the series look like on regular scales.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

January 25, 2022 at 12:20 pm in reply to: Military Spending and Economic Growth in the United States #247620The correlation is between the 10-year trailing average series.

Thank you, Michael, for introducing your work and the useful dialogue.

We learn from disagreement.

Thank you Alexander.

Regarding goodwill.

1. When company A acquires or merges with company B, the owners of company A pay for the assets of company B. The price they pay can be high or low, but the result is merely the transfer of the assets previously held by the owners of B to the owners of A. In this specific sense, mergers and acquisitions merely redistribute the ownership of existing assets.

2. The question you raise concerns the fact that acquired assets often rise in price relative to their per-acquisition stock market valuation (an increase that accountants usually attribute to the emergence of ‘goodwill’). This is a very real process, of course, but I’m not sure why it is an issue for your measure of R. As far as I understand it, R aggregates ‘real’ retained earnings, so when retained earnings are used to acquire ‘overpriced’ assets, the extra price due to goodwill — which is merely a polite way of saying greater power — should be eliminated when these retained earnings are deflated back to ‘real terms’.

Personally, I don’t think that ‘real-term’ measures have anything ‘real’ about them; I think that, conceptually, they are totally bogus. But you cannot hold both ends of the stick: if you measure retained earnings in ‘real terms’, then pure price changes should be eliminated. And if your price deflator cannot achieve this conversion, then the deflation process is invalid.

Regarding the aggregation of ‘real’ retained earnings over time.

I’m not sure what this measure tells us. If the Standard Oil of New Jersey retained $20 million of net earnings in 1890, and if this $20 million was used to pay for drilling equipment, train companies, bribed politicians and what not, how much of this equipment, material or immaterial as the case may be, is still a “resource” in 2022? Your method suggests that all of it is, and you argue further that you know its quantity in ‘real terms’. My opinion is that you cannot know either.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Alexander.

I have been thinking about the problem of what is capital and capitalism. A problem I have with capitalism as power and capital as sabotage of industry is the startup problem. How can capitalist power be exerted when it is weak compared to other powers? And how can sabotaged industry come to dominate over non-sabotaged industry?

Some ideas about how capital as power was born out of feudalism can be found in Capital as Power, Ch. 13: ‘The Capitalist Mode of Power’.

So what is capital? Capital is what capitalists buy with their profits.

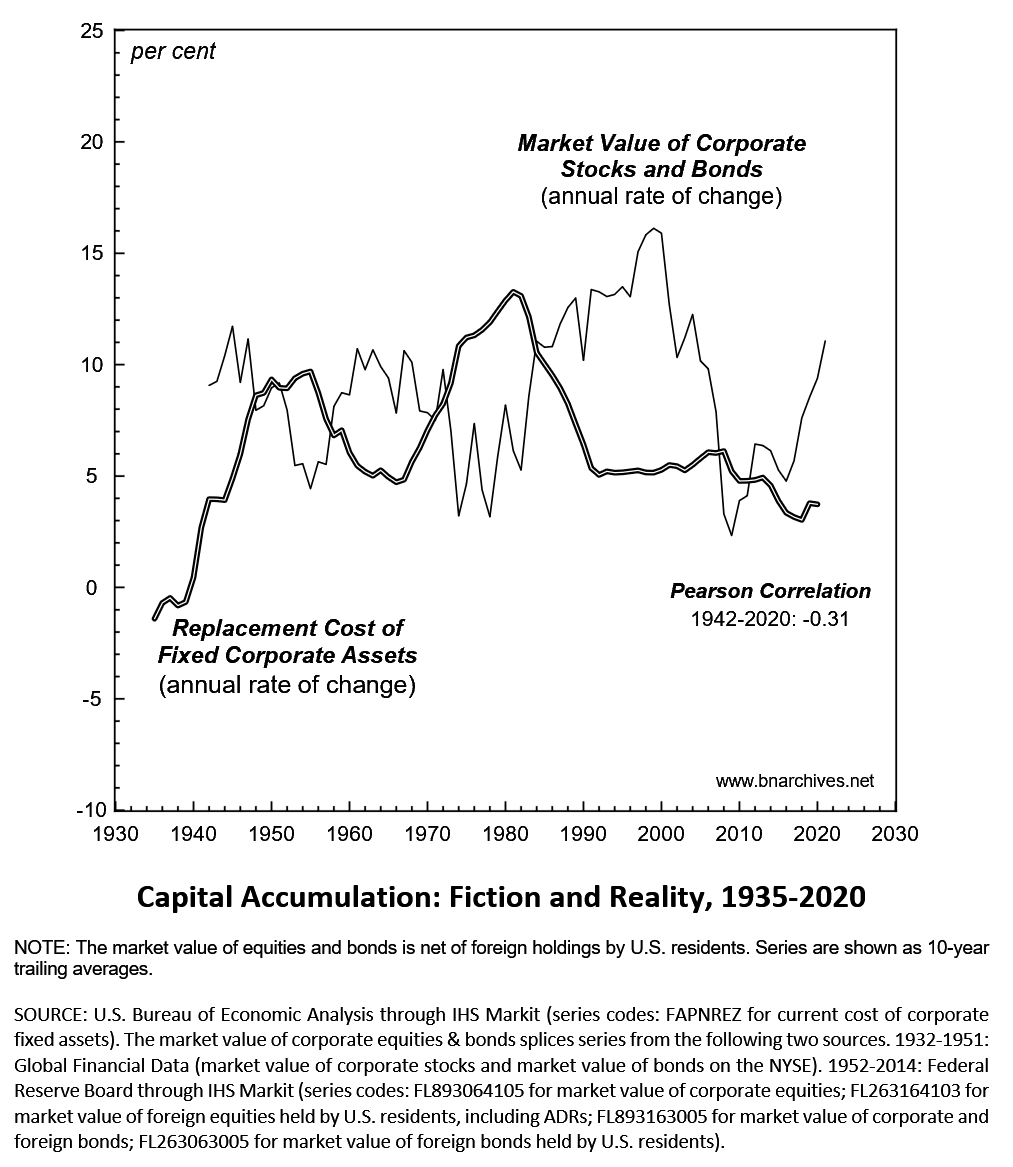

On an aggregate level, what capitalists buy with their profit is plant & equipment, or what economists call ‘real capital’ (buying other companies through mergers or acquisitions doesn’t alter the aggregate of what capitalists own, only redistributes it among them). The problem is that, over the longer haul, the growth rate of the replacement dollar value of ‘real capital’ (economic accumulation) moves inversely with the dollar value of stocks and bonds (financial accumulation). And since for capitalists the key is the latter process rather than the former, economists end up barking up the wrong tree. Here is a graph updated from ‘Capital Accumulation: Fiction and Reality’:

Your aggregation of past retained earnings expressed in ‘real terms’ (R) is backward-looking, so regardless of its theoretical meaning, it’s unclear how it affects forward-looking capitalization.

On ‘real’ measures in economics, see for instance:

- ‘Price and Quantity Measurements: Theoretical Biases in Empirical Procedures’ (1989)

- Capital as Power (2009): Chs. 5 and 8

- ‘The Aggregation Problem: Implications for Ecological and Biophysical Economics’ (2019)

- ‘Real GDP: The Flawed Metric at the Heart of Macroeconomics’ (2019)

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Alexander for this interesting view.

You might find CasP analyses of the stock market useful, even if you disagree with them:

- A CasP Model of the Stock Market (2016) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/494/

- Financial Crisis, Inequality, and Capitalist Diversity: A Critique of the Capital as Power Model of the Stock Market (2020) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/599/

- How the History of Class Struggle is Written on the Stock Market (2020) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/658/

- Reconsidering Systemic Fear and the Stock Market: A Reply to Baines and Hager (2021) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/696/

- The Ritual of Capitalization (2021) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/707/

Thank you for the clear explanation, Alexander.

Here you say:

R is not cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index.

But here you seem to say the opposite:

For a broad-based index, the value of R can be estimated as the sum of retained earnings in constant dollars

Reading your explanations, it seems to me that you express the common backward-looking notion of ‘real capital’ — namely, that this ‘stock’ is made of past earnings invested in plant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc. If I understand you correctly, the difference is that you don’t call this magnitude ‘real capital’ but ‘resources’.

I’m not sure how your view relates to Capital as Power, particularly given (1) that CasP rejects the notion that ‘real capital’ has an objective magnitude, and (2) that capitalization, being the discounted value of risk-adjusted future earning, is theoretically independent of past profit, aggregated or otherwise.

R is not cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index.

P/R is not a ratio of three indices. It is market price of a share divided by the equity value per share with equity calculated on a constant-dollar basis.

I must admit being confused. Forgive me if you have already done so, but could you provide a simple definition + a clear example for both R and P/R?

At the very least, though, the concept of a “market” should require the voluntary exchange of commodities, shouldn’t it?

I don’t think so. All monetary exchange involves aspects of power, so in that sense, it is never entirely or even mostly voluntary. But it is never only about power either. In a company town, the power of the company is significant, but not absolute. If it were absolute — like in a slave plantation or a concentration camp — there would be no need for monetary exchange.

The capitalist mode of power is mediated through monetary exchange. And if exchange is a vehicle of power, you cannot assume it away. In this sense, capitalism sans markets is an oxymoron.

But I could be wrong.

Scot,

Your notion of a “market” refers to the neoclassical setting of perfect competition. But this is only one possible setting, even in neoclassical theory. In capitalism, a market is a setting where commodities are exchanged (usually) for money. This is a very general definition that can accommodate any commodity/ies, participants, institutions and patterns of activity.

If you get rid of this concept, how would you describe the reality it refers to?

-

AuthorReplies