Capital as Power and Freelance Creative Work 4

November 17, 2014

Frederick H. Pitts

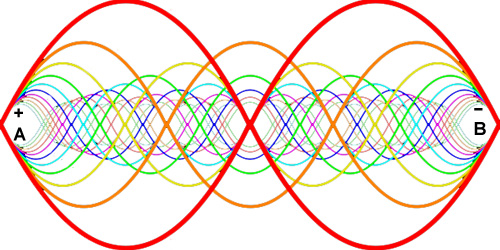

Resonance and dissonance in the rhythms of freelance creative work

In the last blog, I applied some of Nitzan and Bichler’s ideas to freelance work in the creative industries. I utilised their conceptualisation of the distinction between creativity and power, and of the sabotage of the former by the latter. Nitzan and Bichler describe the appearance of this productive tension in terms of resonance and dissonance. In this post, I will explore how we might go about researching the relationship between the two by means of Henri Lefebvre’s method of ‘rhythmanalysis’.

Nitzan and Bichler help us understand the conflicting interests of autonomy and control, responsibility and risk. The delegation of responsibility and the delegation of risk carry with them clashing temporalities and rhythms. Relying on a fragile balance between creative freedom and control, this results in a conflict between rhythms of creativity and power. This dissonance guarantees the success of the creative industries. Success depends upon the calculation and channeling of creative potential, no matter how resistant the latter is to such practices. These practices ensure that creative activity becomes safe, certain and quantifiable. But, at the same time as requiring rationalisation, the creative freedom so restrained provides a foundation for the success itself. This dissonant relationship is essential to capitalistic business operations. In my research, Lefebvre’s rhythmanalytical method has helped ascertain the manifestation of this dissonance.

Nitzan and Bichler suggest that, when free of the pressures of business and power, industry and creativity exist in a state of ‘resonance’ (Capital as Power, p. 226). This is attained where business power fails to exert the optimum amount of control upon affairs. But realistically, this resonance is rarely attained. The harmonious and resonant satisfaction of human wants and desires by means of industriousness and creativity is largely a purely ideal state of affairs. It is antithetical to business’s will to power and control. It offends against the latter’s desire to undermine and disrupt. It prevents the pursuit of differential advantage and, ultimately, accumulation. Business represents a much different rhythmic pattern- one not of resonance, but of dissonance. Capitalist society is a dissonant society, and must be in order to reproduce itself. This is because success in business does not derive from a capitalist entity’s propensity to beat in time with opposing entities. It rather derives from the deviation from the rhythms of others, and to defy the prevailing standard. Not only does business power rely on this conflict between companies, centering on the struggle to always be out of step with one’s competitors and peers. It also depends upon the maintenance of antagonistic relationships of control over workforces. Here, autonomy and creativity are stifled, limited and managed in certain ways. This generates resistances between social groups and rivalry between capitalists. This renders business a dissonant system, quite unlike the supposed (and, of course, largely ideal) resonance of industry. And it is this dissonance that is productive- the tensions which send rhythms out of step are exactly those that drive forward the capacity for capital to be accumulated.

The dissonant influence of business upon industry ‘propels’ accumulation. It forges a profit from the pervading economic circumstances. If business were to conform to the rhythms of industry, it would be naturally be inducted and subsumed into the latter. It would work creatively for the meeting of human needs and wants rather than destructively for the accumulation of wealth and power. The capacity for profit relies upon the ability of business to always exert a disruptive and arrhythmic influence upon the economic scene. As Nitzan and Bichler write, ‘[t]he only way to make a profit is through dissonance. It is only be propelling industry in ways that interfere with and partly hamper its open integration, coordination and the well-being of its participants that business earnings can be appropriated and capital accumulated’ (ibid.).

The research I have been conducting seeks to examine the rhythmic context and content in which freelance creatives can be seen to labour. Through their testimonies, I explore the conflicts, tensions and struggles that determine the rhythms of their working lives. I interpret these rhythms using Lefebvre’s rhythmanalytical method. This method enables me to operationalise some of the concepts delineated by Nitzan and Bichler. Rhythmanalysis is a vehicle for the application of the theory of resonance and dissonance in the relationship between creativity and power. It allows us to explore this relationship in concrete empirical contexts.

Rhythmanalysis is the study of the rhythms and repetitions comprising everyday life. Rhythmanalysis examines the different rhythms created when contrasting social principles synchronise to different degrees. They produce either eurhythmy or arrhythmia depending on the success with which they interrelate. Creativity and power approximate to two such rhythmic poles, and I study the various eurhythmy and arrhythmia that they generate.

Lefebvre suggests that the researcher use pre-formed concepts and categories when examining the field. The researcher thus narrows in from the abstract and general to concrete and specific empirical phenomena. The preformed conceptual apparatus that helps direct me to where rhythms lie derives from the theories of Nitzan and Bichler. They point towards the social practices that express certain rhythms. They allow the application of wider processes to specific social groups and their circumstances. The competing interests of creativity and power manifest as conflicting rhythms in the working lives of creative freelancers.

I use qualitative interviews with creative freelancers as the principal method of data collection. My research thus relies upon the personal testimonies of the experiences of participants. On the one hand, the interviews have focused on the patterns and recurring themes of freelance creative work. and, on the other, the tensions, struggles and conflicts that ensure.

This is in line with Lefebvre’s recommendation that one assesses rhythm from two standpoints. On the one hand, repetition. On the other, difference or disjuncture. The latter fits particularly well as a byword for Nitzan and Bichler’s concept of dissonance.

This difference is what makes rhythmanalysis possible. Of course, without repetition the interpretation of the passing of time and the keeping of rhythm are impossible. But the possibility of knowing and observing rhythm rests the exposure of repetition by deviation from it. The passage of time itself becomes clear with the deviation of phenomena from their usual pattern. The differences that afflict the course of repetition not only make clear to those subject to it the passing of time, but also constitute the very ‘thread of time’ itself (p. 8). It is with difference that the rhythmic conditions under which time proceeds become clear.

Repetition represents the seamless, smooth functioning of the rhythmic pattern of social processes. Thus, it is of limited heuristic possibility: it remains hidden and elusive due to its normality. This repetition constitutes a resonance of sorts, rarely achieved and, when achieved, unremarkable. It expresses little of the upheaval and disruption that renders the circuit of capital so productive and dynamic. Dissonance makes capitalism what it is.

Lefebvre considers difference the only means by which any original or underlying repetition becomes clear in the first place. Indeed, the theory of resonance and dissonance also implies that difference is of more methodological utility than repetition. In my research, I look at disruptions of routines and conflicts of rhythms, through the conduit of participant experience. It is these differences that provide the most fruitful phenomena through which to understand the dissonant rhythms of creativity and power.

The focus of my research is upon uncovering concrete instances where the jarring rhythms manifest. These instances express the difference and dissonance that sustains business profit. The interviews invite the interviewee to express, from his or her own experience, these jarring moments. According to Lefebvre, the disjuncture is something that is sensed and experienced. This may be in either a bodily and physical or social and psychological way. The testimony of the interviewee is thus a suitable means by which we can understand the rhythmic content and context of freelance work in the creative sector. Applying Nitzan and Bichler to Lefebvre, we might say that the system functions around dissonance and difference rather than resonance. The rhythmic differences of this dissonance are best expressed by those subject to the tensions, conflicts and disruptions created.

The theory of capital as power has evident application at the level of wider global processes. But what my research shows is the potential for it to be operationalized at more local levels. The theory of capital as power helps us understand concrete, everyday, micro-level phenomena, as well as the movements of capital as a whole. There is great potential for further work in this area.

Thanks are due to the funding bodies supporting the research.