Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Scot,

You raise many questions, but I think that, at this point, engaging with them will be splitting hair. Perhaps when you write something concrete where these issues become paramount, we can revisit the various metaphors and categories and see whether our differences, if any, matter or not.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Broad concepts/metaphors are always loose and contested.

What/who was the “operational symbol” of Mumford’s original Mega-Machine? Was it the king?

According to Ulf Martin’s The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery, ‘operational symbolism’ appeared only in modernity. The kings in Egypt and Mesopotamia were still locked into ‘magical symbolism’.

Approaching these questions from an entirely different angle, have you considered (or do you assert) that the “state of capital” is logically distinct from the state within whose laws the state of capital operates?

The concept of the ‘state of capital’ begins by defining the ‘state’ as the overall power structure of society and then attributing to it a particular form – ancient kingship, feudal, capitalist, etc. For us, the ‘state of capital’ is a synonym for the ‘capitalist mode of power’. As we see it, the state of capital is the broadest definition of the regime and, in that sense, it contains – rather than being contained by – the normal conception of the state. Thus, in our view, what people normally refer to as the ‘U.S. state’ is part of the state of capital, not the other way around.

From this perspective, capitalism is not a mega-machine, it is a control system (mode of power) whose logic organizes and controls the mode of production for the purposes of perpetuating its control (power).

Isn’t a megamachine a control system? My impression is that this is exactly what Mumford had in mind. But then, metaphors are merely tools to contextualize/enrich/sharpen our understanding, so you can definitely change them to suit your purpose.

What about bank deposits, the value of which are always the par/nominal value of money deposited (assuming no accruing of interest)? Does CasP consider bank deposits as capital? Or does it view bank deposits as “money,” even if it is not in circulation (as the Federal Reserve does)?

We think of bank deposits that pay no interest as capital with zero expected profit. The same applies for any other ‘income-less’ asset.

Second, I agree that the “holder” of the record is immaterial, but is the counter-party to the underlying claim also immaterial? Being the aggregator of and counter-party to all capital imbues Finance with immense power, even though that capital is officially owned by and owed to others.

I’m not sure what you mean by ‘Finance’ with a capital F. We speak about finance with a lower-case f. For us, finance is an operational symbol (in Ulf Martin’s terminology), and that’s it. What most people think of when they speak about Finance is the FIRE sector (finance, insurance and real estate). In our view, this sector is not finance, but merely one institutional/organizational manifestation of finance. As we see it, the FIRE sector, however large, does not control money, credit and debt; the “state of capital” does. It is the ruling capitalist class, its key corporate and government organs and their many-faceted institutions that together dominant and steer the financial process. Banks, insurance and real-estate companies are merely part of that process.

Now, having said that, you are correct that FIRE can and does redistribute income, risks and assets — but so do other sectors, such as raw materials, pharmaceuticals and high-tech firms, sometimes at cross-purposes, sometimes in unison. These redistributional patterns are the details of the differential process of ‘credit at large’ — not the process as such.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Personally, I also take the quote quite literally to mean that “capital” exists only as tallies in accounting records of financial institutions, and these tallies are indicia of wealth owed to the account holder by the institution that maintains the accounting records (e.g., banks and stock brokerages). Of course, all accounting records record capital transactions, even those of a non-financial business, but as a practical matter all “capital” in developed countries “accumulates” as tallies of accounts held in financial institutions.

Scot,

Our claim that “the quantum of capital exists as finance, and only as finance” can be clarified by breaking it into two parts.

(1) Capital is finance. For capitalists, “capital” are record of ownership (stocks, bonds, real-estate claims, etc.) whose quantity is their forward-looking pecuniary capitalization, and forward-looking capitalization is a financial quantum: its magnitude is risk-adjusted expected future earnings discounted by the normal rate of return.

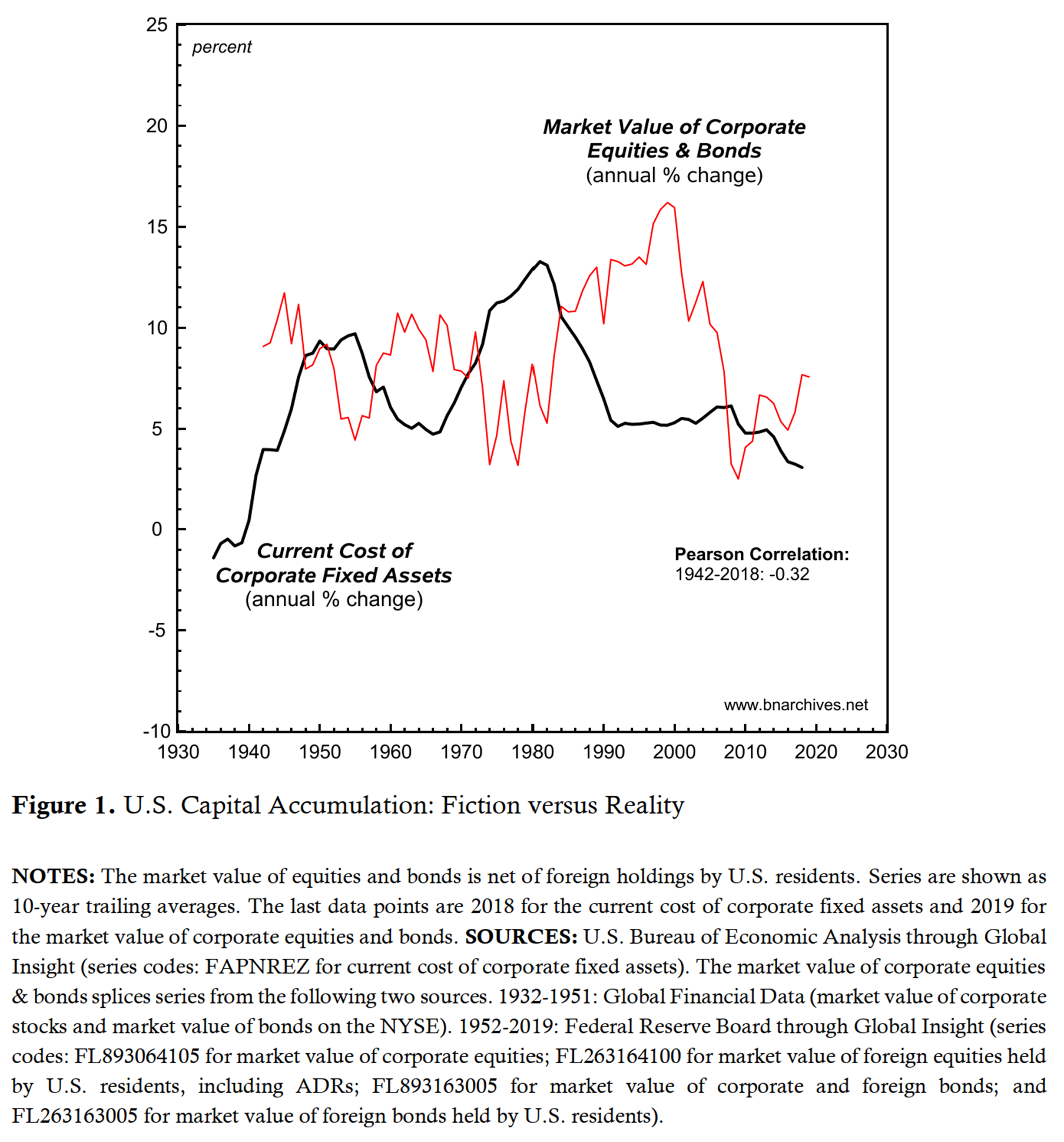

(2) Capital is only finance. The common view that capital=capital goods breaks down because amalgams of heterogeneous capital goods cannot be measured in meaningful ‘real’ units (physical volume, weight, embodied energy, etc., although universal, are not meaningful). Furthermore, even when we measure the money magnitude of capital goods rather than their so-called real magnitude, the movement of this magnitude has little or nothing to do with that of capitalization. In the U.S., the two magnitudes move in opposite directions.

The fact that records of ownership are held by financial institutions is immaterial for these arguments. You could hold them under the mattress and they would still be finance and only finance.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

It’s easy to sense the solid foundation behind CasP and behind your answers but what should I read to get a proper handle on it? I guess I need to read some foundational texts and modern texts. Where do I start and where do I read up to? Can you recommend say five or six texts, any size, all original authors (in English, translations available if necessary) and not surveys unless you regard a given survey as belonging in such a small foundational group of texts.

This is not an easy question to answer, and I’m not even sure it is the right question to ask.

I’ve looked through my library for innovative books that influenced our thinking over the years – studies of society, science and history, as well as novels — and I counted about 100. There is no way for me to rank them by their importance. They all are. But reading alone won’t help anyone ‘find his/her way’, so to speak.

Our own experience taught us that to develop our opinion – rather than to adopt the opinion of others – we must do our own empirical/historical research. One reason is that research allows us to ask and perhaps answer questions that others haven’t. But the more important reason, I think, is that it sharpens our sense of judgment. Research allows us to better discern what question are important and what are secondary, or unimportant; which subjects are crucial and which less so, or not at all; which opinions are innovative, and which are silly; etc.

For this reason, I make my course work research dependent. My students, both undergraduate and graduate, are given two empirical assignments and a final theoretical-empirical term paper. The first assignment asks them to mimic my own empirical work; the second makes them answer a series of empirical questions; and the final one requires that they both invent and answer their own theoretically-inspired empirical questions (see https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/702/).

Not everyone is cut for this type of work. But in each class, there are some students who rise to the challenge, and in due course, some of those become first-class political economic researchers. I can also attest that many of these would-be experts started my class with no prior background in political economy, mathematics, and statistics.

So, I know that this method works – and, most importantly, that it is open to anyone. You don’t need to be a university professor, a PhD student, or a math wizard. You only need to be young, regardless of your age.

I hope these notes are useful.

However, when I encounter statements like “Science cannot tolerate logical contradictions,” I become concerned. I am not entirely sure what is meant. Does it mean CasP is pure science and cannot tolerate contradictions?

Let me try to explain.

When scientists encounter logical contradictions — namely, when their theories make contradictory propositions — they become restless and try to resolve these contradictions. Some of the greatest advances in the history of science relate to resolving logical contradictions, usually by proposing new concepts/theories (plus empirical research) that eliminate those contradictions.

The bifurcation of politics and economics tends to generate logical contradictions. When economics assumes self-equilibrating, atomistic markets, this assumption contradicts the recognition by other social scientists that there exist large corporations, governments, unions, NGO and crime syndicates, not to speak of larger networks/hierarchies of these entities. When economists assume that humans are driven by absolute utility maximization, this assumption contradicts the recognition by many other social scientists that humans seek relative power. When economists assume (usually unknowingly) that they can aggregate ‘real’ magnitudes based on individual utility, this assumption is contradicted by other social scientists who think that humans are different from each other and therefore that their utilities cannot be added, that people are often very irrational, that they are largely unaware of their preferences/utilities, and that most of their preferences/utilities are not their own in the first place. I can go on, but I think the point is clear.

Economists treat such contradictions by declaring that one element is a ‘distortion’ of the other, but this treatment leaves the contradictions intact.

How then does CasP deal with human and human system contradictions such as irrationality? Does it mean CasP limits its field of investigation and is not attempting to resolve such contradictions?

I don’t think irrationality per se is a logical contradiction. The logical contradiction arises when the theory assumes that human are always rational as well as that they are often irrational. CasP doesn’t assume that people are rational or irrational. It observes that the thoughts/actions of human beings are shaped, at least in part, by the hierarchical structure in which they exist, and that the result often seems irrational to us (though usually not so to the rulers). It also recognizes that humans are capable of autonomy, and that, under certain circumstances, they might create autonomous relations and perhaps even autonomous societies. Since the position of society on this spectrum is not a starting assumption, but something to be examined, it does not generate logical contradictions of the type I mentioned earlier.

More on these issues: The Capital As Power Approach. An Invited-then-Rejected Interview with Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

Analytically, ‘economics-politics dualists’ — namely all economists, Braudel’s included — begin by conceiving capitalism as a self-regulating atomistic economy, and then tuck on power as a ‘distortion’. This is akin to physicists assuming 4 elements and then adding everything else they know as a ‘distortion’.

Science cannot tolerate logical contradictions — and yet that is exactly what splitting politics from economics ends up doing.

US Lobbying numbers for 2021 (Jan-Sept). Pharmaceuticals industry spends twice the second highest industry (Electronics).

Interesting data, Chris.

(Parenthetically, I think you mean the ‘pharmaceutical business’, not the ‘pharmaceutical industry’.)

Has any progress been made in mapping out the COP-MOPs of capitalism and, especially, its predecessor modes of power?

It’s work in progress.

In the meantime, and if you haven’t already, you might want to have a look at Di Muzio’s The Tragedy of Human Development. A Genealogy of Capital as Power.

My arithmetic was not meant to imply that reading novels was a chore.

Of course not. My answer was a tongue-in-cheek clarification for others….

And thank you for the additional suggestions!

Arithmetic aside, reading is a joy, not a chore.

Yes, the branding of companies based on their ‘home state’ has become increasingly anachronistic.

Thank you Scot.

I am a little confused by the conclusion that “(2) the relative power of U.S. capital continues to wane,” which appears to be based on your discussion regarding Figure 3 and “net profit shares. ”

1. The conclusion is based on Figures 2 and 3.

I thought power (and, therefore, relative power) is determined by market value (i.e., capitalization), not by net profit shares (i.e., earnings multiplied by the number of shares outstanding). By factoring out share price, you’ve eliminated any consideration of differential discount rates and differential “hype,” which conceivably could result in lesser profits representing greater power. What do the relative market capitalization data show?

2. You are correct that, according to our CasP view, differential capitalization is the ultimate power yardstick, and that differential profit gives only a partial picture. However, there is something to be gained by looking at net profit only, since, over the very long haul, it is the main driver of capitalization.

In any event, here is the figure for the global distribution of market capitalization. The downtrend of the U.S. share is not as steep as in the net profit figure, but it is negative nonetheless. And remember that these data start only in the mid 1970s. My hunch is that the U.S. share of global market capitalization in the 1950s was higher.

Thank you James and (mostly) Blair for making it happen.

This is part of a wider project that James McMahon and I are trying to get off the ground.

Excellent.

-

AuthorReplies