Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

What about bank deposits, the value of which are always the par/nominal value of money deposited (assuming no accruing of interest)? Does CasP consider bank deposits as capital? Or does it view bank deposits as “money,” even if it is not in circulation (as the Federal Reserve does)?

We think of bank deposits that pay no interest as capital with zero expected profit. The same applies for any other ‘income-less’ asset.

Second, I agree that the “holder” of the record is immaterial, but is the counter-party to the underlying claim also immaterial? Being the aggregator of and counter-party to all capital imbues Finance with immense power, even though that capital is officially owned by and owed to others.

I’m not sure what you mean by ‘Finance’ with a capital F. We speak about finance with a lower-case f. For us, finance is an operational symbol (in Ulf Martin’s terminology), and that’s it. What most people think of when they speak about Finance is the FIRE sector (finance, insurance and real estate). In our view, this sector is not finance, but merely one institutional/organizational manifestation of finance. As we see it, the FIRE sector, however large, does not control money, credit and debt; the “state of capital” does. It is the ruling capitalist class, its key corporate and government organs and their many-faceted institutions that together dominant and steer the financial process. Banks, insurance and real-estate companies are merely part of that process.

Now, having said that, you are correct that FIRE can and does redistribute income, risks and assets — but so do other sectors, such as raw materials, pharmaceuticals and high-tech firms, sometimes at cross-purposes, sometimes in unison. These redistributional patterns are the details of the differential process of ‘credit at large’ — not the process as such.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Personally, I also take the quote quite literally to mean that “capital” exists only as tallies in accounting records of financial institutions, and these tallies are indicia of wealth owed to the account holder by the institution that maintains the accounting records (e.g., banks and stock brokerages). Of course, all accounting records record capital transactions, even those of a non-financial business, but as a practical matter all “capital” in developed countries “accumulates” as tallies of accounts held in financial institutions.

Scot,

Our claim that “the quantum of capital exists as finance, and only as finance” can be clarified by breaking it into two parts.

(1) Capital is finance. For capitalists, “capital” are record of ownership (stocks, bonds, real-estate claims, etc.) whose quantity is their forward-looking pecuniary capitalization, and forward-looking capitalization is a financial quantum: its magnitude is risk-adjusted expected future earnings discounted by the normal rate of return.

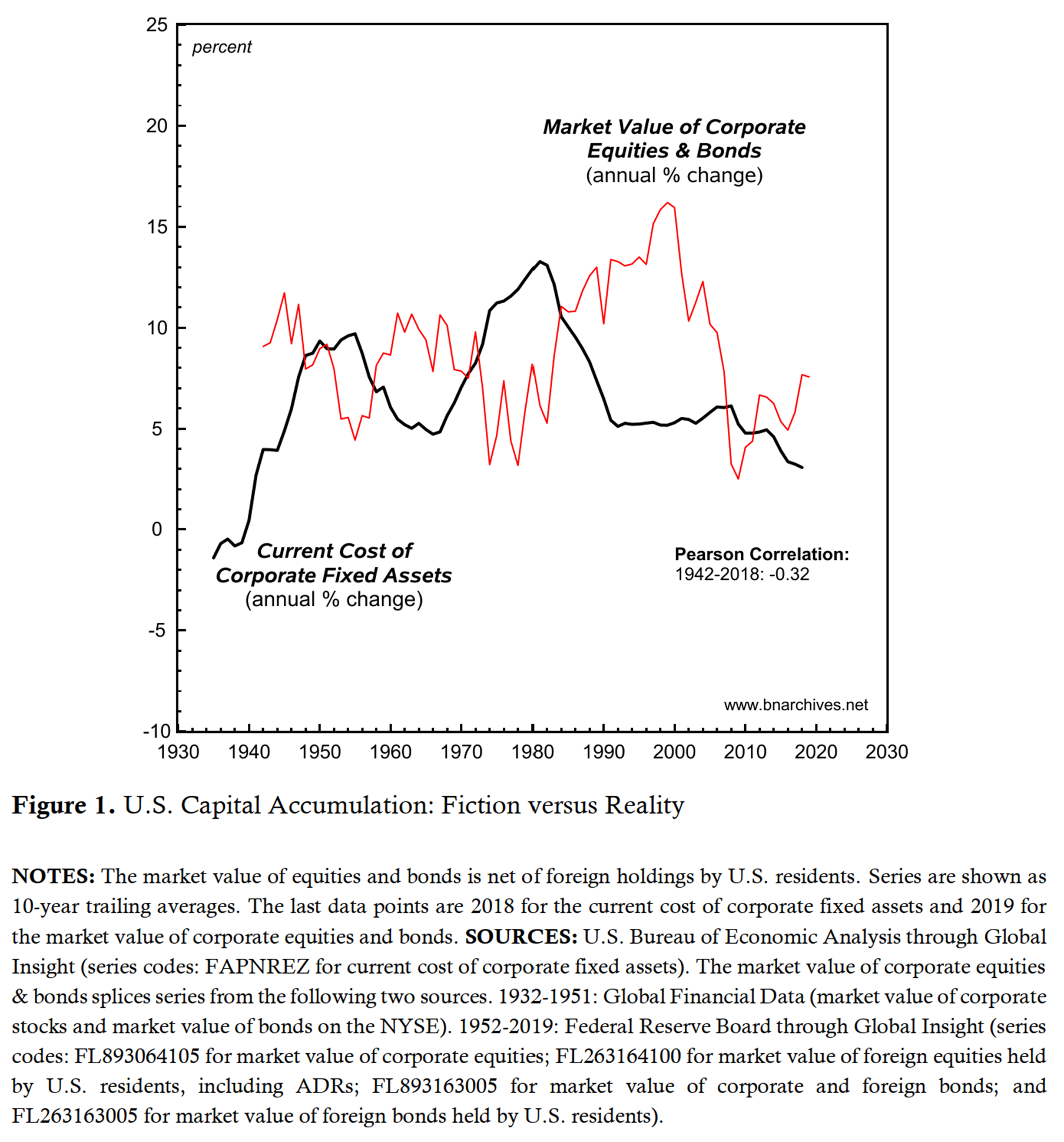

(2) Capital is only finance. The common view that capital=capital goods breaks down because amalgams of heterogeneous capital goods cannot be measured in meaningful ‘real’ units (physical volume, weight, embodied energy, etc., although universal, are not meaningful). Furthermore, even when we measure the money magnitude of capital goods rather than their so-called real magnitude, the movement of this magnitude has little or nothing to do with that of capitalization. In the U.S., the two magnitudes move in opposite directions.

The fact that records of ownership are held by financial institutions is immaterial for these arguments. You could hold them under the mattress and they would still be finance and only finance.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

It’s easy to sense the solid foundation behind CasP and behind your answers but what should I read to get a proper handle on it? I guess I need to read some foundational texts and modern texts. Where do I start and where do I read up to? Can you recommend say five or six texts, any size, all original authors (in English, translations available if necessary) and not surveys unless you regard a given survey as belonging in such a small foundational group of texts.

This is not an easy question to answer, and I’m not even sure it is the right question to ask.

I’ve looked through my library for innovative books that influenced our thinking over the years – studies of society, science and history, as well as novels — and I counted about 100. There is no way for me to rank them by their importance. They all are. But reading alone won’t help anyone ‘find his/her way’, so to speak.

Our own experience taught us that to develop our opinion – rather than to adopt the opinion of others – we must do our own empirical/historical research. One reason is that research allows us to ask and perhaps answer questions that others haven’t. But the more important reason, I think, is that it sharpens our sense of judgment. Research allows us to better discern what question are important and what are secondary, or unimportant; which subjects are crucial and which less so, or not at all; which opinions are innovative, and which are silly; etc.

For this reason, I make my course work research dependent. My students, both undergraduate and graduate, are given two empirical assignments and a final theoretical-empirical term paper. The first assignment asks them to mimic my own empirical work; the second makes them answer a series of empirical questions; and the final one requires that they both invent and answer their own theoretically-inspired empirical questions (see https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/702/).

Not everyone is cut for this type of work. But in each class, there are some students who rise to the challenge, and in due course, some of those become first-class political economic researchers. I can also attest that many of these would-be experts started my class with no prior background in political economy, mathematics, and statistics.

So, I know that this method works – and, most importantly, that it is open to anyone. You don’t need to be a university professor, a PhD student, or a math wizard. You only need to be young, regardless of your age.

I hope these notes are useful.

However, when I encounter statements like “Science cannot tolerate logical contradictions,” I become concerned. I am not entirely sure what is meant. Does it mean CasP is pure science and cannot tolerate contradictions?

Let me try to explain.

When scientists encounter logical contradictions — namely, when their theories make contradictory propositions — they become restless and try to resolve these contradictions. Some of the greatest advances in the history of science relate to resolving logical contradictions, usually by proposing new concepts/theories (plus empirical research) that eliminate those contradictions.

The bifurcation of politics and economics tends to generate logical contradictions. When economics assumes self-equilibrating, atomistic markets, this assumption contradicts the recognition by other social scientists that there exist large corporations, governments, unions, NGO and crime syndicates, not to speak of larger networks/hierarchies of these entities. When economists assume that humans are driven by absolute utility maximization, this assumption contradicts the recognition by many other social scientists that humans seek relative power. When economists assume (usually unknowingly) that they can aggregate ‘real’ magnitudes based on individual utility, this assumption is contradicted by other social scientists who think that humans are different from each other and therefore that their utilities cannot be added, that people are often very irrational, that they are largely unaware of their preferences/utilities, and that most of their preferences/utilities are not their own in the first place. I can go on, but I think the point is clear.

Economists treat such contradictions by declaring that one element is a ‘distortion’ of the other, but this treatment leaves the contradictions intact.

How then does CasP deal with human and human system contradictions such as irrationality? Does it mean CasP limits its field of investigation and is not attempting to resolve such contradictions?

I don’t think irrationality per se is a logical contradiction. The logical contradiction arises when the theory assumes that human are always rational as well as that they are often irrational. CasP doesn’t assume that people are rational or irrational. It observes that the thoughts/actions of human beings are shaped, at least in part, by the hierarchical structure in which they exist, and that the result often seems irrational to us (though usually not so to the rulers). It also recognizes that humans are capable of autonomy, and that, under certain circumstances, they might create autonomous relations and perhaps even autonomous societies. Since the position of society on this spectrum is not a starting assumption, but something to be examined, it does not generate logical contradictions of the type I mentioned earlier.

More on these issues: The Capital As Power Approach. An Invited-then-Rejected Interview with Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

Analytically, ‘economics-politics dualists’ — namely all economists, Braudel’s included — begin by conceiving capitalism as a self-regulating atomistic economy, and then tuck on power as a ‘distortion’. This is akin to physicists assuming 4 elements and then adding everything else they know as a ‘distortion’.

Science cannot tolerate logical contradictions — and yet that is exactly what splitting politics from economics ends up doing.

US Lobbying numbers for 2021 (Jan-Sept). Pharmaceuticals industry spends twice the second highest industry (Electronics).

Interesting data, Chris.

(Parenthetically, I think you mean the ‘pharmaceutical business’, not the ‘pharmaceutical industry’.)

Has any progress been made in mapping out the COP-MOPs of capitalism and, especially, its predecessor modes of power?

It’s work in progress.

In the meantime, and if you haven’t already, you might want to have a look at Di Muzio’s The Tragedy of Human Development. A Genealogy of Capital as Power.

My arithmetic was not meant to imply that reading novels was a chore.

Of course not. My answer was a tongue-in-cheek clarification for others….

And thank you for the additional suggestions!

Arithmetic aside, reading is a joy, not a chore.

Yes, the branding of companies based on their ‘home state’ has become increasingly anachronistic.

Thank you Scot.

I am a little confused by the conclusion that “(2) the relative power of U.S. capital continues to wane,” which appears to be based on your discussion regarding Figure 3 and “net profit shares. ”

1. The conclusion is based on Figures 2 and 3.

I thought power (and, therefore, relative power) is determined by market value (i.e., capitalization), not by net profit shares (i.e., earnings multiplied by the number of shares outstanding). By factoring out share price, you’ve eliminated any consideration of differential discount rates and differential “hype,” which conceivably could result in lesser profits representing greater power. What do the relative market capitalization data show?

2. You are correct that, according to our CasP view, differential capitalization is the ultimate power yardstick, and that differential profit gives only a partial picture. However, there is something to be gained by looking at net profit only, since, over the very long haul, it is the main driver of capitalization.

In any event, here is the figure for the global distribution of market capitalization. The downtrend of the U.S. share is not as steep as in the net profit figure, but it is negative nonetheless. And remember that these data start only in the mid 1970s. My hunch is that the U.S. share of global market capitalization in the 1950s was higher.

Thank you James and (mostly) Blair for making it happen.

This is part of a wider project that James McMahon and I are trying to get off the ground.

Excellent.

However, how can we forget China?

We are silence on China because we don’t understand and read any of its languages and are dubious of its data. CasP research of China will have to be done by people who can read the languages and assess the data.

Dominant Capital and the Government

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan[1]

Originally published on The Bichler and Nitzan Archives.

***

This note contextualizes the ongoing U.S. policy shift toward greater ‘regulation’ of large corporations. Cory Doctorow (2021) and Blair Fix (2021) are optimistic about this shift. We doubt it.

1. The Limits of Power

Large U.S.-based corporations are extremely powerful, but the growth of their power has decelerated considerably.

Figure 1, updated from our ‘Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2021), shows the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of the top 200 U.S.-based corporations, ranked by market capitalization, relative to those earned by the average U.S. corporation. The top series confirms that this differential – which proxies the relative power of the top 200 firms – has grown exponentially, rising from roughly 1,000 in 1950 to more than 15,000 in the 2000s. The bottom series, though, shows that the rate at which this differential power has grown trends downwards.

This long-term deceleration is not accidental. In fact, it is built into the very nature of social power. In our capital-as-power research – or CasP, for short – we argue that power always elicits resistance from those on whom it is imposed; that this resistance tends to rise along with power; and that the greater the resistance the more difficult it is to augment power even further. In other words, power is self-limiting (Bichler and Nitzan 2012, 2016, 2020).

The twenty-first century revival of anti-corporate sentiments and anti-capitalist movements around the world is part of this resistance – as are some of the policy reforms emerging in their wake. But these reforms shouldn’t be over-hyped.

2. The Capitalist Mode of Power

Our CasP analysis claims that, as capitalism develops, governments and large corporations become increasingly intertwined organs of the same capitalist mode of power. We call this mode of power the ‘state of capital,’ and we label the large government-backed corporate coalitions at its core ‘dominant capital’.

The coalescence of governments into the capitalist mode of power does not mean that ‘policymakers’ can no longer take an independent stance. They can. But the likelihood of them doing so, as well as the scope of their independence, tend to diminish as the capitalist mode of power creorders – or creates the order of – more and more aspects of social and private life. As this corporate-government integration unfolds, government organizations and officials, including ‘reformers’, not only get entangled in the web of capitalized power, but they also find themselves conditioned by its very concepts, symbols, ideologies and rituals. Consequently, most of them cannot even conceive of fundamental change, let alone bring it about.

From this broad perspective, a meaningful shift within capitalism – and certainly a shift away from it – is less and less likely to come from above. If this shift is to materialize – and in our view, the current prospects for it remain dim – it is likely to come not from reformist governments and soulful corporations, but from below or from without. It will be affected either by social movements mobilized by radical rethinking of capitalized power, or by environmental calamity. Finally, and importantly, this change is likely to materialize not peacefully, but conflictually.

3. Why are Neoliberal Governments so Big?

Think of contemporary governments. Since the 1980s, neoliberal ideology has demanded that state ‘intervention’ and ‘regulation’ be scaled back. It has called for capitalist efficiency to substitute for bureaucratic red tape, for market transparency to replace state corruption, and for equal opportunity to displace hierarchical power. It insists that government should stop ‘crowding-out’ private investment and cease interfering with the so-called free market. It argues that for markets to expand, governments must shrink.

And yet, as Figure 2 shows, the victory of neoliberalism hasn’t made government any smaller. Not by a long shot. In high-income countries, the national income share of government consumption spending remains as large as it was before the onset of neoliberalism, while in low- and middle-income countries, it continues to grow bigger and bigger.

And that shouldn’t surprise us. The capitalist mode of power and the dominant-capital coalitions that rule it do not require small governments. In fact, in many respects, they need larger ones.

As a mode of power, capitalism thrives on multiple forms of ‘strategic sabotage’ – that is, on limiting and redirecting the energy of human beings toward the augmentation of capitalizing power. Dominant capital prevents most people from cooperating, democratically and directly, to improve the well-being of their society and environment. Instead, it forces them to fortify and amplify the very capitalized power that dominates them. And this forcing requires a whole slew of threats, limitations, and the open use of force – in other words, it begets strategic sabotage.

The thing is that, left unregulated, strategic sabotage can easily overbuild, causing the mode of power to implode under its own weight. And that’s where government spending comes in as a mitigating force. From this viewpoint, bigger government – particularly its sprawling social programs and transfer payments – mirrors not the failure of neoliberalism, but its very success.

Figure 3 shows the changing importance of federal transfer payments in the United States. The dashed series depicts the level of current expenditures by the federal government, expressed as a share of U.S. national income. Note that these expenditures include purchases of goods and services, as well as transfer payments for which no goods and services are rendered in return. The solid series displays the share of transfer payments in overall current federal expenditures.

The relationship between the two proportions is telling. Initially, the association was negative. During the 1930s and 1940s, when the national income share of current federal expenditures increased, the share of transfers in these expenditures declined – and vice versa when government expenditures fell. This inverse relationship means that transfers were relatively stable, and that most of the ups and downs in federal spending were due to ups and downs in current government consumption.

But soon enough the relationship flipped. From the 1950s onward, the national income share of current federal expenditures trended upward – and, for the most part, this uptrend was driven by a relentless increase in the share of transfers. All in all, during the postwar era, this share rose 13-fold – from less than 5 per cent in the early 1940s, to nearly 65 per cent presently.

With this observation in mind, it is perhaps worth noting that the 2020 Covid19-related surge in current federal spending – a surge that many like/hate to think of as active ‘Keynesianism’ – was accounted for mostly by passive transfers.

The gradual shift from discretionary expenditures on goods and services to reactive transfers is typical of many governments around the world, and it suggests that these governments are far less potent than their size might imply. In fact, one can argue that the bigger ‘transfer states’ of today are far weaker than the smaller ‘consumption states’ of the Keynesian era. Their apparent largess indicates not greater power but subjugation: a built-in deference to dominant capital, whose strategic sabotage must be offset, at least in part, by unemployment insurance benefits, welfare payments and the like.

4. Summary

On paper, the U.S. government is free to legislate its path and determine its policies. In principle, there is little to prevent a resolute U.S. administration from challenging the power of the country’s dominant capital and clip the wings of its largest firms.

But it would be good to remember that the U.S. government – like most other governments – has become part and parcel of an increasingly global state of capital. This integration has undermined the de facto autonomy of governments everywhere. Whether willing or reluctant, many if not most policymakers have become pawns of a global mode of power they cannot control and that forces them to tranquilize the increasingly vulnerable population that dominant capital helps create. Government spending has inflated, but this inflation betrays weakness, not strength.

Larger-yet-weaker neoliberal governments are the alter-ego of bigger-and-meaner dominant capital. It is hard to think of any important sector or aspect of society, in the United States and elsewhere, where dominant capital does not dominate. It is true that, faced with increasing resistance, the rising power of dominant capital in the United States has slowed down significantly over the years and seems to have stalled completely in recent times (Figure 1). But the level of this power is still greater than ever, and it is yet to show any meaningful decline. Finally, and importantly, the stalling advance of U.S. dominant capital makes it extra vigilant against any serious challenge.

Prediction: if the current U.S. government delivers on its promise to curtail the might of the country’s largest corporations, it will face the wrath of the most powerful megamachine the world has ever seen.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Work on this note was partly supported by SSHRC.

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2012. The Asymptotes of Power. Real-World Economics Review (60, June): 18-53.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2016. A CasP Model of the Stock Market. Real-World Economics Review (77, December): 119-154.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2020. The Limits of Capitalized Power. A 2020 U.S. Update. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2020/06, December): 1-16.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2021. Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism. Real-World Economics Review Blog, January 4.

Doctorow, Cory. 2021. End of the Line for Reaganomics. Capital as Power Blog, September 26.

Fix, Blair. 2021. How Dominant are Big US Corporations? Economics from the Top Down, September 29.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies