Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

You focus on analysts, but how well do analysts predict earnings (figure 1, CasP, p. 213)?

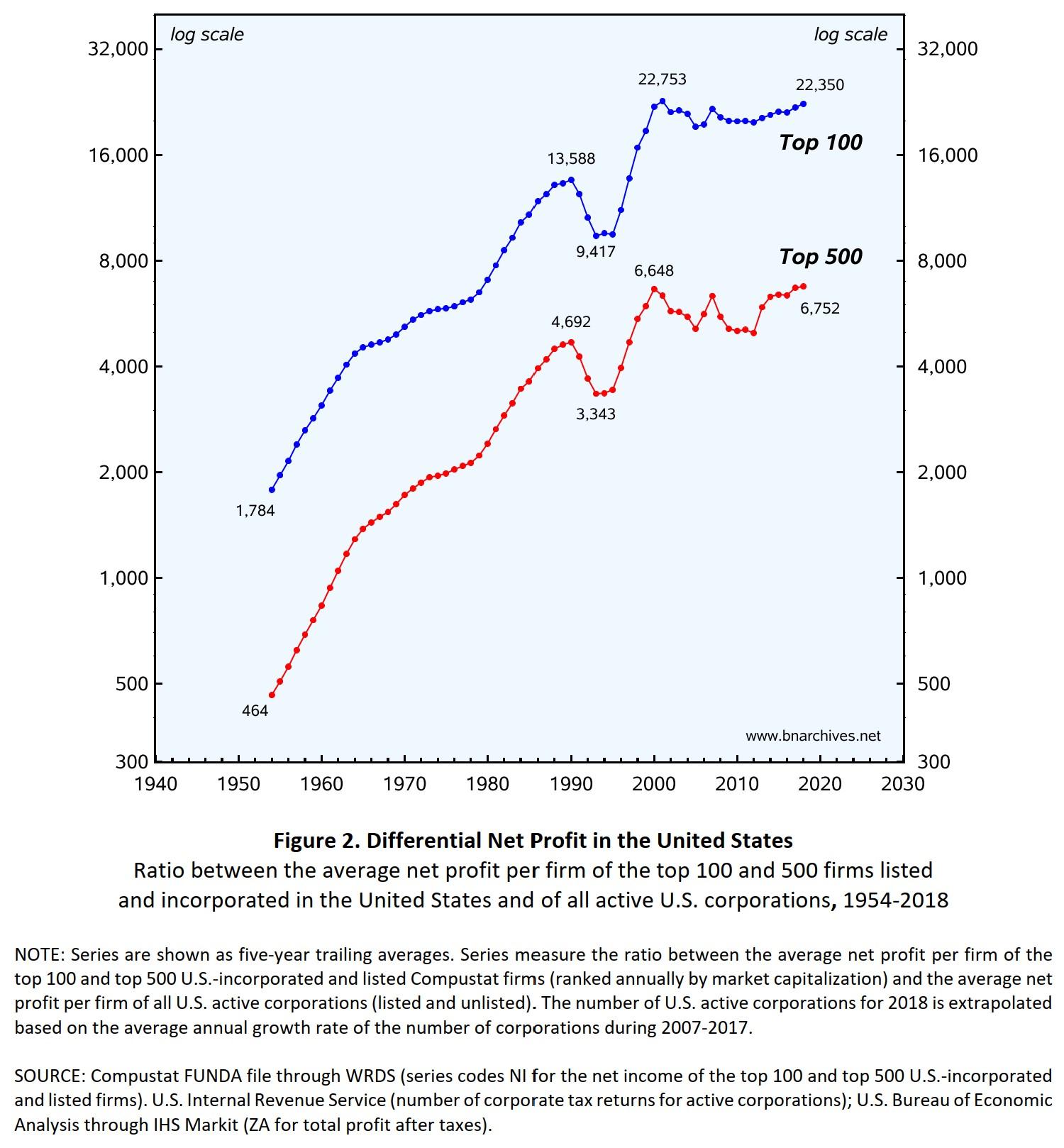

And I think that stock prices normally do not correlate with current earnings; or to put it more precisely, that their correlation with current earnings (rather than future earnings) is closely related to the level of capitalized power — the greater the power, the higher the correlation (figure 2, The CasP Stock Market Model, p. 141).

And even when stock prices do correlate with current earnings — as they have in the past couple of decades, when capitalized power has soared — it seems to me that causality still runs from earnings to prices, not the other way around. But, then, I might be wrong.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

1. Yes, reduced risk perceptions increases capitalization, but you mentioned findings that were not in James’ work.

2. Yes, of course. Companies do all sort of things, including trying to project next quarter’s earnings. But capitalization tends to look into the deep future, which is unknowable and unverifiable here and now. And I think that, in general, it is these long-term earning expectations that drive capitalization.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

1. James’ work on Hollywood showed that the leading firms didn’t manage to increase their differential earnings. Instead, they reduced their differential risk.

2. Regarding the causal chain between earnings and capitalization (of both interest as debt and profit as equity), I think you might be putting the cart before the horse. Conceptually, capitalization is based on expected future earnings, so that, all else remaining the same,

greater earnings expectations –> larger capitalization

The thing is that, in practice, capitalization occurs before the future interest and profit are earned, leading to the (false?) conclusion that

larger capitalization –> greater earnings

In retrospect, firms that see their capitalization increase are driven to accommodate that increase by higher earnings, lest they crash, but the original impetus for that higher capitalization was greater earning expectations.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

May 31, 2021 at 10:19 pm in reply to: A proposition of “ecological antiturst” (as a potential research subject?) #245736Brian —

I think the relationship between energy and hierarchy is double-sided.

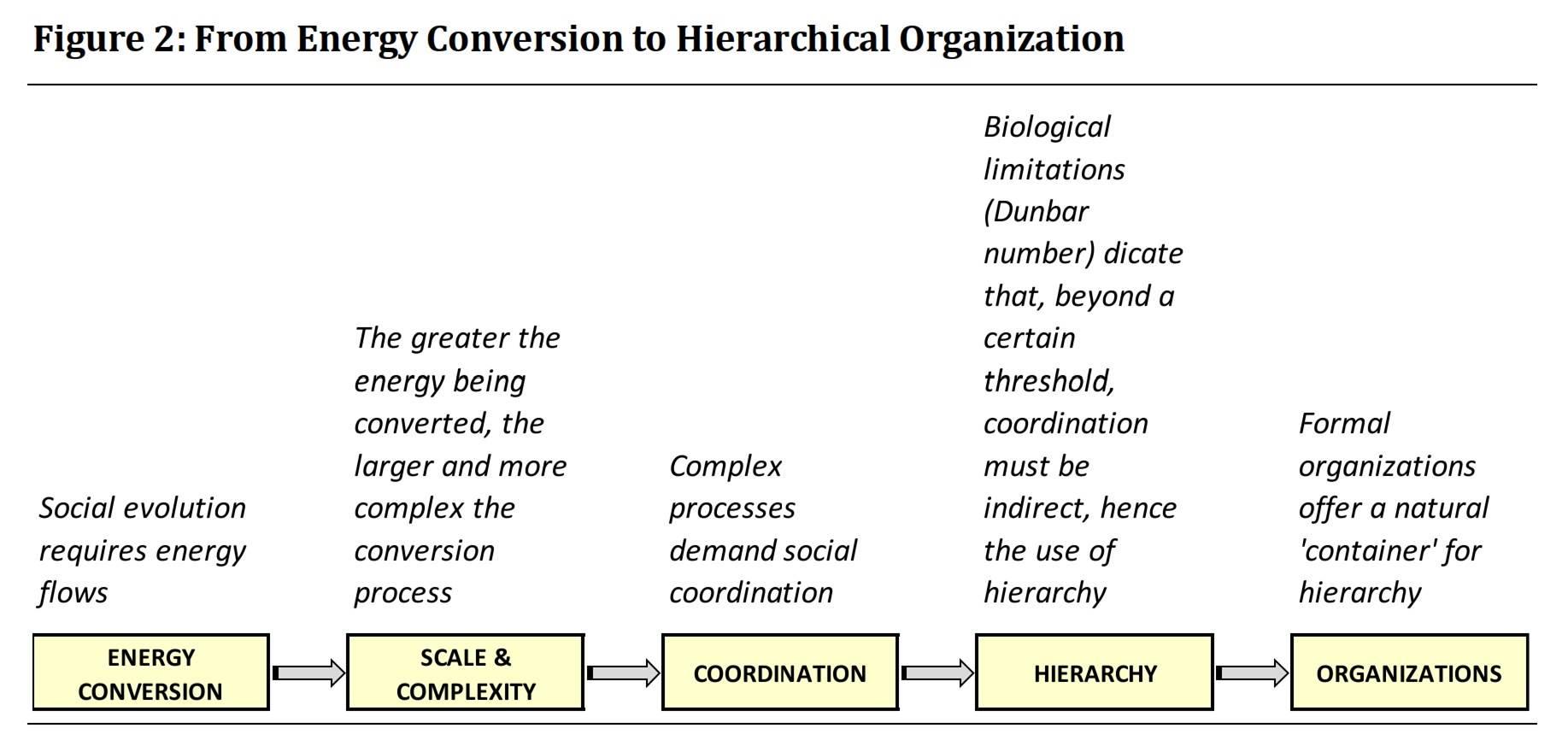

Blair’s superb work emphasizes the notion that hierarchy is a means to capturing energy: to capture more energy, humans need larger and more complex organizations, and the most effective way of organizing complex human organizations is hierarchically:

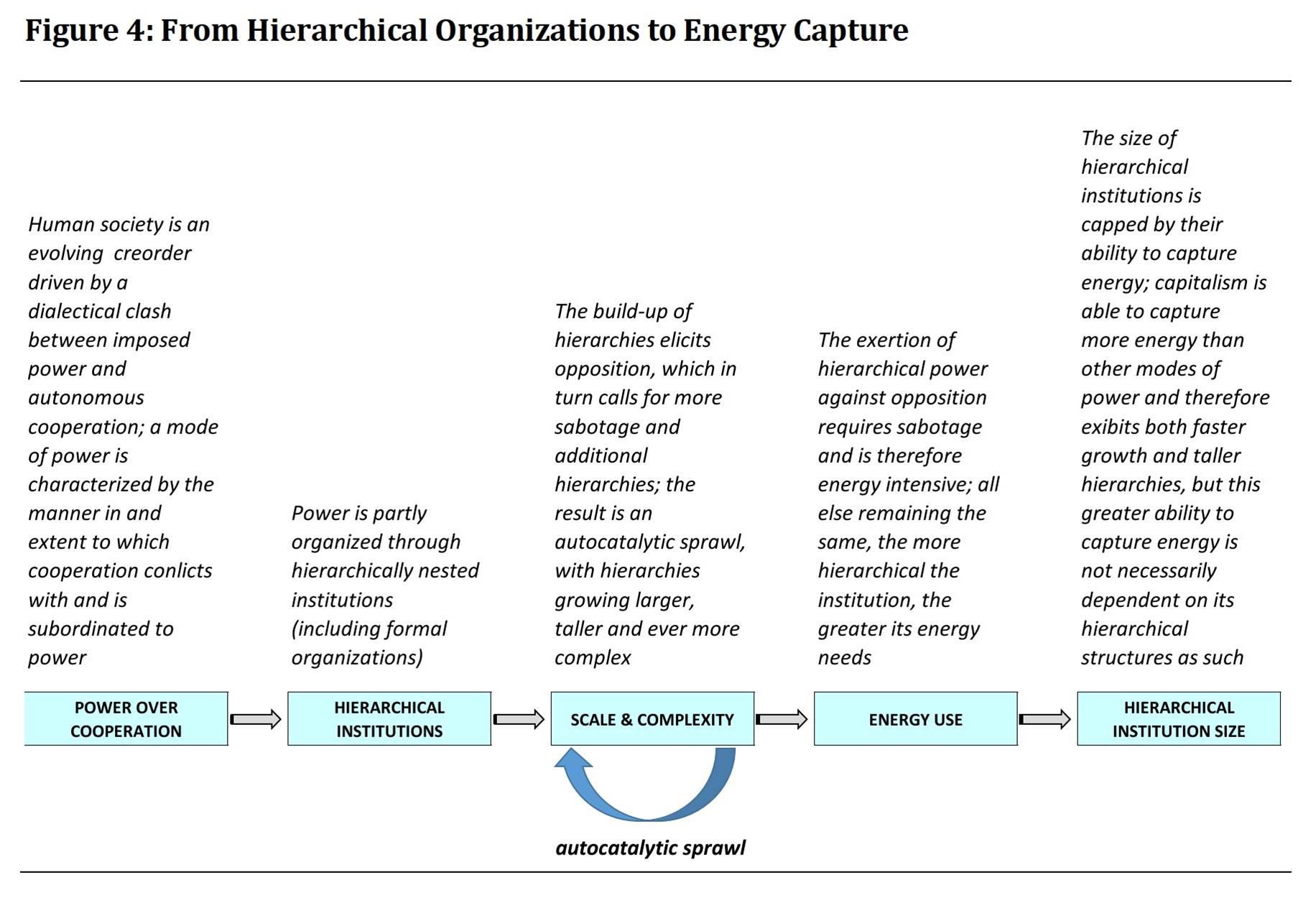

The other explanation is that civilization (say from Sumer onward) is driven by the quest for hierarchical power, and to construct this hierarchical power requires energy. This argument can be described as follows:

The two explanations need not be mutually exclusive, though we need much more theory/research to decipher them and understand their relationships.

You might find our 2020 paper on this subject relevant: ‘Growing Through Sabotage’.

Unfortunately, at this point CasP is primarily a framework for understanding capital as power in broad brush strokes. It’s dialectical approach relies on a aggregate data, which is good for identifying the existence of power (through trends that seemingly defy conventional wisdom) and opposition to that power (through apparent tensions that demonstrate a lack of confidence in obedience), but which offers very little when it comes to actually understanding the underlying “mega-machinery” of capitalism

Yap. CasP has plenty of room to expand. In the meantime, here is a small sample of “fine brush” insights into the “underlying mega-machinery of capitalism”:

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Brian, here is a 2014 dialogue we had with a fund manager on the subject of the ‘The Enlightened Capitalist‘.

You might find it relevant to your questions.

Thanks Brian.

There are no ‘correct’ answers to you questions, of course, but here are some thoughts.

Our claim in ‘capital as power’ is not that capital is ‘affected’ by power, but that it is literally a symbolic representation of power — and nothing but power. In our view, this power is meaningful only because it presses against and tries to reduce and eliminate opposition and resistance. Without this opposition and resistance — from within capital as well as from outside of it — power has no meaning.

1) From the viewpoint of CasP, does the issue of corporate governance – whether a company should serve only shareholders or serve stakeholders too – matter, in the context of the accumulation of capital and concentration of power?

I’m not sure CasP has anything to say about this ‘should’. Personally, I prefer to eliminate hierarchical private corporations in favour of various forms of flat democratic cooperation. In practice, the control and purpose of corporations are constantly contested. So far, though private owners and differential accumulation via strategic sabotage seem to be winning, big time. This trajectory can change in the future, but I don’t see it on the horizon.

2) There have been talks on “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)” and now recently “ESG” due to more public interests in climate change. From the viewpoint of CasP, *should* corporations (or *can* they )serve the society in general? And how would CSR/ESG look like in reality?

Currently, large corporations are hierarchically structured, intertwined with other hierarchical networks, including governments, and tend, almost exclusively, to seek differential accumulation through various forms of strategic sabotage. In principle, corporations can be — and have been — regulated, restricted and reformed in various ways. But in my view, these regulations, restrictions and reforms are limited: judging by the continuous rise of differential accumulation by dominant capital, these ‘countervailing forces’ are no match to the power of large owners (see the U.S. chart below from http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/671/). According to Blair Fix’s work, hierarchy tends to grow with energy capture, so as long as growth continues, so will the size of large corporations and other hierarchies. Again, this ongoing victory of capital can change — perhaps through a massive crisis — but we are not there yet.

3) How does CasP see Galbraith’s call for countervailing force or stakeholder governance to contain corporate power? Does it have at least some merit?

In my opinion, countervailing powers might ‘work’ when both sides seek power — for example, when corporations fight other corporations. In these cases, mutual threat creates a semblance of stability, however tentative.

But trying to have ‘stakeholders’ restrain differential accumulation is a different matter. In my view, the main problem is that the two sides have fundamentally different goals. Corporations and owners seek power, know how to use it and have no scruples exerting it. Stakeholders, by contrast, seek wellbeing, have limited expertise in using power, and are usually restrained by self-imposed, well-meaning inhibitions. In this sense, ‘stakeholders’ tend to fight with their hands tied behind their back.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

May 25, 2021 at 11:43 am in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245701Let me summarize my understanding of your reply (and add a few comments/observations):

1. Banks do face a repayment risk, but this risk can be eliminated (though I’m not sure I understand how they can eliminate it without foregoing or undermining their expected profit).

2. Finance (banks?) creates risk primarily by making ‘bad bets’ (isn’t this true of all capital?).

3. Financial crises are associated mainly with speculation. Finance often initiates these crises through its relation with speculators — but this initiation happens not because it lends to speculators per se, but because it insists they repay their debt — and in ‘hard cash’ to boot (Isn’t all investment/lending ‘speculative’ – i.e. future dependent? Isn’t debt always a ‘collectable asset’ until capitalists realize/admit it isn’t?)

4. My comments suggest that the topic we deal with is both technical and theoretically foundational to negotiate cryptically as we have done here.

5. Your question about my dissertation: perhaps you’ll figure the answer after reading it.

6. “I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics”. That’s your prerogative.

7. I look forward to seeing your ideas articulated in a systematic piece!

May 24, 2021 at 8:47 pm in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245695Thanks for the interesting reply, Scot.

1. Bank-originated money. Thank you for the links. I’m familiar with these claims, though I’m not sure how they affect our exchange here. Yes, private banks can create deposits and loans in one fell swoop, but this ability has no bearing on the fact that the loans – be they to corporations, NGOs, governments or individuals – are eventually withdrawn from the accounts in order to be utilized; that they have to be repaid with interest in the future; and that occasionally they are not. Isn’t this last fact a risk for the banks?

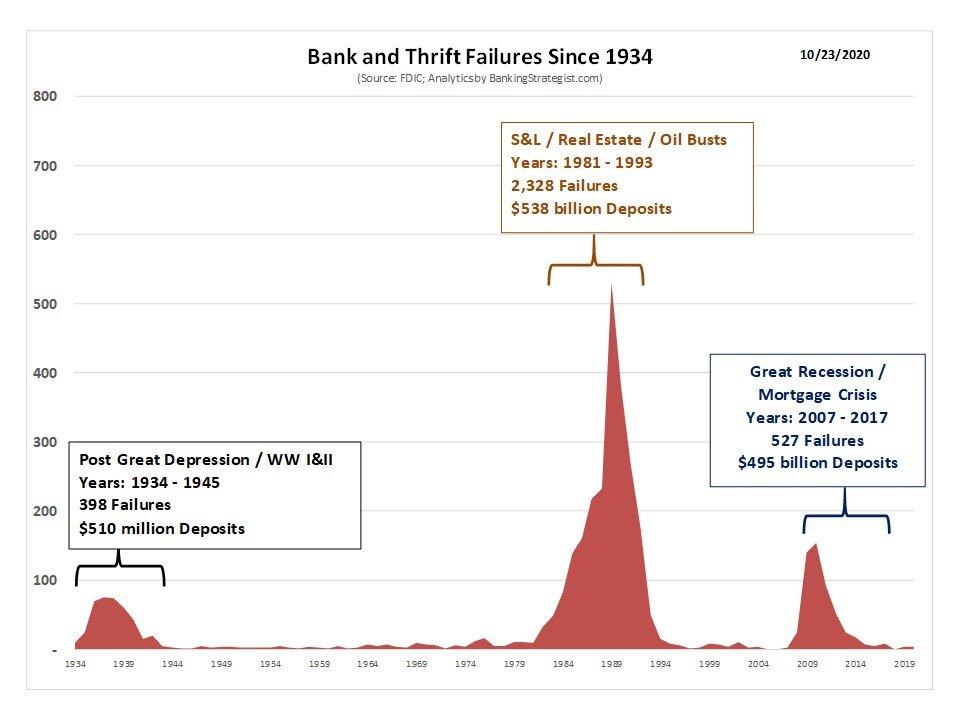

2. The facts. Over the past two centuries, banking crises affected between 5-30% of all countries on an ongoing basis (first figure). In the U.S., banks fail all the time – and occasionally, they fail spectacularly (second figure). Aren’t these crises and failures evidence that banks are risky?

[1] Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2008. This Time is Different: A Panoramic View of Eight Centuries of Financial Crises. March. NBER Working Paper Series (13882): 1-124. https://www.nber.org/papers/w13882

[2] https://www.bankingstrategist.com/history-of-us-bank-failures

3. Capitalization. The act of capitalization does not occur in the balance sheet, which is backward-looking. It happens in the equity/debt market which is forward-looking. In this sense, banks are like every other corporation: their ultimate goal is to augment their capitalization by raising their discounted risk-adjusted expected income. That’s why corporations, including banks, are in business.

4. Balance sheets. The balance sheets of banks are similar to those of non-bank corporations in that their owners/managers can enlarge them, often at will. Non-bank corporations can do it by borrowing and/or issuing stocks; banks can do it by issuing stocks but mostly by extending loans against deposits (external or self-created). In both cases, the expansion occurs because the owners/managers think it will increase their expected risk-adjusted earnings. But neither banks nor other corporations expand their balance sheets without end. And why not? Because debt leverage and equity dilution are risky.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

May 24, 2021 at 8:17 am in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245689Thank you Scot.

fiat money is not the issue, credit money is.

Yes, the issue is credit/debt money, but the system of credit/debt money cannot exist with commodity money. It needs fiat money – money by decree — as its denominator.

a commercial lender puts no existing capital or money at risk when it extends interest-bearing credit to a “borrower,”

I’m not sure I follow. Loans and the interest on them — including those made by commercial banks — are expected to be paid in the future. The fact that borrowers may not repay them makes these ‘extensions’ risky. This risk is mitigated by different forms of power, including government backing of the private banking system, but to say it does not exist seems to me odd given the nature and turbulent history of credit and banking more specifically. (Perhaps you mean that banks lend other people’s money rather than their ‘own capital’, but that fact makes them no less risky.)

credit money is what drives the need for the perpetual exponential growth of credit, money end economic growth, as well as “differential accumulation” more broadly

We’ll have to disagree on that. In my view, credit money is a facet of capitalization, not the other way around.

the discussion of “rituals” and “symbols” (and “COP-MOP” pairs) makes it more difficult to understand CasP and its value in providing a framework for describing Capitalism as a control system

Needless to say, you are welcome to offer easier-to-understand explanations!

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

May 22, 2021 at 6:17 pm in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245683[…] it is the delegation of the sovereign power of money to private parties that is the ultimate source of capital’s power, e.g., […] it is private control over money, wages and prices that gives rise to the “depth regime” of sabotage.

Thank you Scot for the clarification.

I think there is a certain tautology to your argument. You say, and I paraphrase a bit, that the privatization of money is an important if not the ultimate source of capital’s power. You can similarly say that the private control of pharmaceuticals, energy, transportation, entertainment, construction, agriculture, biotechnology, education, advertisement, religion and what not are also sources of capital’s power.

According to CasP, capital is private by definition, so for something to become capital, it must first be privately owned.

Regarding the argument that the privatization of money creation is the ‘source’ of capital’s power.

(1) I think the issuance of money is never entirely private; like all forms of private power, it too is always backed by and intertwined with some form of governmental agency. Without this fusion, private money is bound to collapse (think of the early princely bonds issued by medieval rulers to private investors, or speculate what will happen to the U.S. private banking system without government oversight and backup).

(2) Conceptually and ontological, fiat money is based on forward-looking credit: i.e., the capitalization of risk-adjusted expected future returns. To get the process of money creation going, private banks have to issue loans, and these loans are nothing but capitalized profit expectations. In this sense, the modern system of money is a derivative of capitalization, not its cause. And if this argument is correct, the privatization of money cannot be thought of as the ‘source’ of capital’s power.

(3) More generally, in our opinion (Shimshon’s and mine), power has no single ‘source’, or ’cause’, let alone an ultimate one. In modern times — say since 1600 — power is considered a quantified relationship between entities. In society, these quantified relationships are creordered by human beings and organizations through various hierarchies of sabotage and resistance. Increasingly, these powers appear as as differential relations of capitalization/credit (including the institution of fiat money), but this appearance is not a cause, at least not in our opinion. It is merely the ‘operational symbol’, in Ulf Martin’s language, the quantified ritual with which modern capitalism expresses and negotiates its various hierarchies. At any given time, these symbols serve restrict and condition the boundaries of the possible, but they are also incredibly flexible, so that, over time, they can accommodate ever new forms of hierarchical power.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

May 22, 2021 at 12:10 pm in reply to: Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie? #245680From this perspective, the outright rejection of these foundational false dualities prevents CasP from fully understanding the source and nature of capital’s power

I’m not sure I understand your claim. Perhaps you can use the following example to illustrate it.

In our work, we suggested that, during the second half of the 20th century, the Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition supported Middle-East Energy Conflicts to boost its differential accumulation-read-power (for example, ‘New Imperialism or New Capitalism?’ 2006, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/203/).

Do you think that ignoring the presumable politics-economics duality here prevented us from understanding the power of this coalition?

***

To clarify, we do not ‘reject’ the politics-economics duality. As we reiterate in our work, this duality is inherent in the way capitalism is framed virtually by all observes (except CasPers, maybe). Instead, we argue that, when it comes to the actual processes of accumulation, this duality has no operational meaning in the sense that capital discounts all forms of power, regardless of the specific rubrics they are hashed into.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Some thoughts.

1. “The” market is vague enough to pin down, so it is hard to decide whether it “exists” or not. Conceived as the overall system of pecuniary exchange, I think we can say it exists. The thing is that there is no agreement on the precise nature of this system, and it is this lack of agreement that makes the question of whether “the” market exists or not difficult to answer.

2. “A” market is less vague. Economists usually define any given market by (1) the commodity in question, (2) the geographical scope and (3) the time frame. Of course, here too there are ample disagreements — first on the boundaries of these three items, and second and more broadly on the institutions that underpin them. Ask economists to define the “market for computer chips”, “automobiles” or “health services” and you get more answers that you wish to consider and no clear way to decide which of them is “valid.”

3. I think that in capitalism, the only safe way to use the term “market” is in reference to pecuniary exchange. For example, we can say that “we live in a market society” (i.e. a society dominated by pecuniary exchange), or that there is a “market for cars” (a physical/virtual space where cars are traded for money). But the specific character of this pecuniary exchange is open-ended, both ontologically and epistemologically.

I’m sure more words can be spilled on this subject, but I’ll stop here.

Thank you for the interesting reply, Scot.

1. Bridges would be very nice, provided they are not forced or impossible. In general, we find CasP bridges difficult to build since, in certain important respects, CasP is incommensurable with conventional political economy. (See ‘Unbridgeable’, 2021, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/681/.)

2. You disagree with our claim that all commodities are ‘creatures of the social imagination’, writing that ‘Wheat is wheat. Steel is steel. Labor is labor. Etc.’ But wheat, steel and labor are not commodities. They are mere objects. They become commodities only when they are priced. As an object, a ‘ton of steel’ is qualitatively different from a ‘common stock of Tesla’. As commodities, though, they are qualitatively identical and differ only in price. From a CasP viewpoint, this latter universality — the fact that both can be quantified in dollars — is a creature of the social imagination.

3. You suggest that ‘the Market’ does not exist. Perhaps, but to assess this claim we must first agree on what ‘the Market’ is.

I think Polanyi is correct in saying that the idea and institutions of the so-called “self-regulating market” were enforced on society rather than emerged from it organically.

But in one crucial respect, Polanyi’s view is still completely different than if not totally opposed to CasP.

Polanyi claims that the politics-economics duality is both real and false. And yet, when it comes to capital, he accepts it fully. Like all other political economists, capital for him is an ‘economic’ entity. His Great Transformation is concerned almost solely with the emergence of capitalism. It offers no alternative concept of capital. In fact, it does not deal with this concept at all. He accepts the triple economic division of industrial-commercial-financial capital, and he goes on to argue that humans, land and money are ‘fictitious’ commodities – implying that other commodities are not.

In CasP, there is no division between industrial, commercial and financial capital: all capital is finance and only finance. Moreover, all commodities – i.e. all priced items — are creatures of the social imagination. Lastly and most importantly, capital is the commodification of power writ large, and therefore transcends the politics-economy duality to start with.

I should also mention that Polanyi’s notion/critique of the ‘self-regulating market’ — which he shares with many other heterodox thinkers — is also very different than CasP’s. The following section is from our Capital as Power (2009: 306-7):

The power role of the market cannot be overemphasized – particularly since, as we have seen throughout the book, most observers deny it and many invert it altogether. Analytically, the inversion proceeds in three simple steps. It begins by defining the market as a voluntary, self-regulating mechanism. It continues by observing that such a mechanism leaves no room for the imposition of power. And it ends by concluding that power and market must be antithetical, and that they can coexist only insofar as the former ‘manipulates’ and ‘distorts’ the latter.

An example of this inversion is Fernand Braudel’s historical work Civilization & Capitalism (1985). According to Braudel, capitalism negates the market. In his words, there is a conflict between a self-regulating ‘market economy’ on the one hand, and an anti-market ‘capitalist’ zone where social hierarchies ‘manipulate exchange to their advantage’ on the other (Braudel 1977; 1985, Vol. 1: 23–24 and Vol. 2: 229–30). A similar sentiment is expressed by Cornelius Castoriadis, when he proclaims that ‘where there is capitalism, there is no market; and where there is a market, there cannot be capitalism’ (1990: 227).

The root of the error here lies right at the assumptions. Capitalism cannot negate the market because it requires the market. Without a market, there can be no commodification, and without commodification there can be no capitalization, no accumulation and no capitalism. And the market can fulfil this role precisely because it is never self-regulating (and since it is never self-regulating, there is nothing to ‘manipulate’ or ‘distort’ in the first place). Price is not a utilitarian–productive quantity, but a power magnitude, and the market is the very institution through which this power is quantified. Without this market mediation of power, there can be no profit and, again, no capitalization, no accumulation and no capitalism.

And there’s more. The market doesn’t merely enable capitalist power, it totally transforms it. And it achieves this transformation by making the capitalist mega-machine modular. The blueprint of this new machine, unlike those of earlier models, is very short. Its essential component is the capitalization/accumulation formula. The formula is special in that it doesn’t specify what the mega-machine should look like. Instead, it stipulates a ‘generative order’, a fractal-like algorithm that allows capitalists to reconstruct and reshape their mega-machine in innumerable ways. The algorithm itself changes so slowly that it seems practically ‘fixed’ (the basic principle of capitalization hasn’t changed much over the past half-millennium). But the historical paths and outcomes generated by this algorithm are very much open-ended, and it is this latter flexibility that makes the capitalist creorder so dynamic.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies