Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Data waiting for a researcher:

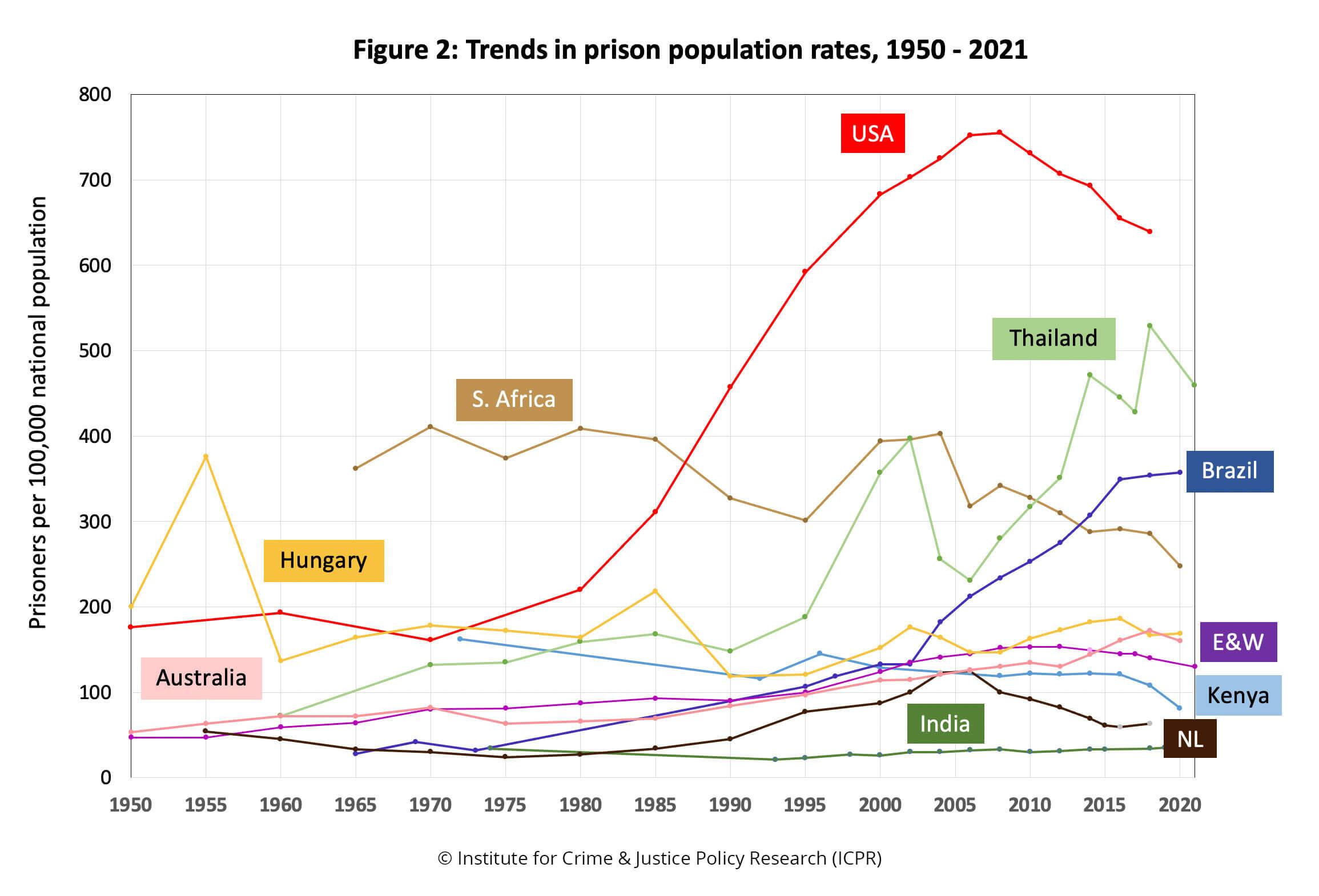

This chart from the WPB shows individual time series for prison population by country. Dividing each series by the the country’s population from the World Development Indicators database gives the incarceration rate. And the incarceration rate can be correlated with income inequality draw from the World Inequality Database.

The standard monetarist argument, put in its most simplistic form, is that inflation is driven by rising liquidity (liquidity=money stock/production). But for that argument to hold, the rise in liquidity must come before the increase in inflation.

This graph, taken from our 2002 book The Global Political Economy of Israel, shows it is the other way around: Israeli inflation has led the rise of liquidity!

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Hi Chris:

1. From power to inflation, or from inflation to power?

In my view, the interesting question is not the effect of power on inflation, but rather what inflation can tell us about power.

From our CasP perspective, modern power is observed as a quantitative relationship between entities. In capitalism, the ultimate manifestation of this relationship is differential capitalization. You can also examine the components of this power, one of which is differential prices (and their rate of change — namely, differential inflation).

From this viewpoint, it makes little sense to say that ‘a lack of workers’ power prevents a rise in future inflation’, simply because nobody knows the future pricing power of workers. Instead, I think it makes more sense to say that the fact that there is currently only limited inflation suggests that workers have limited power and therefore are unable to help fuel it here and now.

2. Absolute versus differential inflation

From our CasP viepoint, inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional process. This means that what matters is not the absolute but relative rates at which prices change. Furthermore, the redistributional patterns of inflation may or may not correlate with its absolute levels. This is something that can be deciphered only through empirical research. (For more, see Inflation as Restructuring.)

3. Do asset prices fuel inflation?

Over the longer haul, higher asset prices need to be ‘validated’ by higher profit (and/or lower risk and normal rates of return), and profit can indeed be increased by inflation. But for that to happen, capitalists must be able to raise their differential prices, and I doubt that this ability is connected to asset prices as such.

4. Does low inflation means more M&A?

In our opinion, the answer is no. In our work, we argued that differential accumulation depends mainly on M&A and stagflation, and that the conditions underlying these two processes are contradictory, so they tend to move counter-cyclically to each other. However, these tentative observations do not mean that there must be either M&A or stagflation. Instead, we simply suggest that at least one of these processes is required for differential accumulation, and that if dominant capital is unable to achieve either, it will end up with no differential accumulation or might suffer differential decumulation.

Regarding the ‘free-cash-flow’ argument made in the third footnote of our piece.

To reiterate, the claim against Figure 2 in our research note is that (1) capitalists discount not net earnings, but the free cash flow; and (2) that, in the case of pharmaceutical firms, the relative magnitude of the free cash flow (compared to the average) is higher than the relative magnitude of net earnings (compared to the average).

If the relative magnitudes of the free cash flow and of market capitalization are the same, it follows that capitalists see the future growth of pharmaceutical free cash flow and/or risk as being the same as the average.

But that is not what the data indicate.

Instead, they show that:

1. In terms of magnitudes, the relative shares of market capitalization > net earnings > free cash flow.

2. In terms of trends, the slopes of market capitalization > net earnings > free cash flow.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

From an accounting perspective, there is no way around the fact that capitalists consume their capital goods, they do not accumulate them.

I don’t mean to begin a debate on this issue, just a couple of notes:

1. I don’t think economists think capitalists accumulate any given capital good. Obviously, individual capital goods depreciate. But in the view of economists, capitalists not only replenish the overall capital stock, they also cause it to grow. For them, one of the key hallmarks of capitalism is a growing physical capital stock, made of an-ever shifting array of capital goods and measured in value-read-money-in-‘constant-prices’ (figure below).

2. One has to distinguish accounting from so-called economic depreciation. Accounting depreciation is determined by accounting rules. So-called economic depreciation is determined, supposedly, by the (productive) value of the capital good. In practice, national accounting statistics measure depreciation differently that company accountants.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Capital goods supposedly transfer their value (in utils or SNALT) to the products they create, and, according to the neoclassical view, they even have an additional productivity to boot, so they create more value than their own.

According to economic theory, both Marxists and NC, capitalists do not accumulate this or that item; they accumulate the value embedded in items. The items may change, but value doesn’t. It transmutes itself as it jumps from item to item….

Moreover, according to Irvin Fisher, this view is intimately connected with capitalization:

Fisher, Irving. 1896. What is Capital? The Economic Journal 6 (24, December): 509-534.

Here is a schematic description of his argument:

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Here is a brief research note summarizing our argument on the capitalist outlook:

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2021. Pharmaceuticals: Beating the Hell Out of the Average. Research Note (June): 1-5.

More to come.

Max:

1. Both PE ratios — for the pharma sector and for the world — have trended mildly upward over the period.

2. The long-term trend of the ratio of PE ratios (pharma PE / World PE) has been virtually flat at roughly 1.5 (eye balling).

3. You are correct: the positive ratio of PE ratios implies expectations for differential profit growth and/or differential risk reduction. In our ongoing research, we show that this is what happened historically: the pharma sector outperformed on both counts.

The ultimate tale about eco-physics is Robert Harris’ book The Fear Index. Here is our own reflection on it.

Yes, finding the “optimal” mathematics to guide a bunch of hooligans trying to control other hooligans as well as the rest of us. That’s what capitalists hire econo-physicists for.

Ishi,

1. PI (Power Index) and HMI (Hussman’s Mismatch Index) were coined by us, so there was no reason for you to hear about them before reading our paper.

2. PI is predicted by the theory, as well a predictor (for example, of the ‘Fear Index’). But our work is limited to the United States. For international research, see Baines and Hager and McMahon.

3. Physicists are welcome to fit differential equations to these relationship and/or derive them from “optimization principles”, whatever they may be. I’m not sure how any of this would relate to our work, but they are welcome to do their thingy if they want to, and we can then judge whether this thingy is useful.

4. In their Laws of Chaos (1983: 97), Farjoun and Machover introduce the ‘law of increasing productivity of labour, or decreasing labour-content’ as follows:

This law amounts, roughly speaking, to the seemingly commonplace observation that as a capitalist economy develops, and as techniques of production develop with it, it takes less labour-time to produce the same product.

As far as I can see, this ‘law’ has nothing to do with our ‘CasP model of the stock market’.

5. Ex ante, ex post and causality are complicated concepts.

But did that profitability result in differential capitalization compared to other S&P 500 companies?

I don’t know the answer to this question with respect to pharmaceuticals and the S&P500 in the U.S., but I can say something about the global scene.

The figure below is part of my current work-in-progress with Shimshon on the pharmaceutical companies.

The chart shows the distributive share of listed pharmaceutical firms in the net profit and market capitalization of all listed firms in the world (as provided by Datastream).

The data suggest that, over the past half century:

(1) both shares have trended upward;

(2) their long-term movements have been positively correlated; and

(3) generally, the pharmaceutical share of market capitalization has been greater than its net profit share.

So, on the face of it, there is basis to think that (1) differential profit growth has driven differential market capitalization growth, and (2) investors expect differential profit growth to accelerate (hence the larger PE ratios implied by the relationship between the two differential indices in the chart).

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Hi Scot,

I appreciate the context. When I worked as an editor at BCA Research in the early 1990s, I learned that ‘long term analysis’ meant projecting the next 18 months. I also learnt that seasoned strategists are skeptical of quantitative models and prefer telling stories. The models, they told me, are necessarily backward-looking, and since the world constantly changes, their forward-looking predictions always fail. Of course, analysts don’t have a choice. Since their rulers crave certainty, they, as fortune tellers, are forced to pretend — even though they almost always err, often big time.

My argument in this thread, though, was not about the clergy of financial analysis, but about the conceptual causal chain between the growth of current capitalization and future earnings, a relationship that we both consider crucial.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

You focus on analysts, but how well do analysts predict earnings (figure 1, CasP, p. 213)?

And I think that stock prices normally do not correlate with current earnings; or to put it more precisely, that their correlation with current earnings (rather than future earnings) is closely related to the level of capitalized power — the greater the power, the higher the correlation (figure 2, The CasP Stock Market Model, p. 141).

And even when stock prices do correlate with current earnings — as they have in the past couple of decades, when capitalized power has soared — it seems to me that causality still runs from earnings to prices, not the other way around. But, then, I might be wrong.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

1. Yes, reduced risk perceptions increases capitalization, but you mentioned findings that were not in James’ work.

2. Yes, of course. Companies do all sort of things, including trying to project next quarter’s earnings. But capitalization tends to look into the deep future, which is unknowable and unverifiable here and now. And I think that, in general, it is these long-term earning expectations that drive capitalization.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies