Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Labban asks: “Has capital accumulation been completely liberated from production? This seems to be the conclusion drawn from reading Nitzan and Bichler.”

Hmmm.

I have no idea where Labban concocts this claim from. It certainly doesn’t come from us, or from any CasP work I know of.

Our research reiterates, again and again, that capital is not about production, but about the control of production. But that doesn’t delink capital from production. Indeed, the very purpose of CasP research – our own as well as that of others — is to understand the ways in which capital creorders – or creates the order of – society, including its productive activity.

Now, given that capital is partly about the control of production, it is rather obvious – although not to Labban — that it cannot be ‘liberated’ from it.

But, then, maybe I misunderstand Labban’s misunderstanding….

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

You haven’t misinterpreted anything, Adam: qualitative research is as important as quantitative research, and facts always require theoretical interpretations — just as theory can rarely stand without empirical work.

Thanks for your posts Adam.

1.

Irrespective of your theoretical approach and whether you will be able to incorporate it in your PhD dissertation, empirical analysis is important. In many cases it’s essential. Without it, you often end up wandering in the dark, getting your cues from other blindfolded writers who in turn get theirs from other blindfolded experts. From my own experience, empirical analysis is important for the answers it gives, but more so for the questions it raises. It will likely change your research trajectory many times over, and in ways that cannot be achieved without it.

One of my former graduate students was once advised by a Marxist professor to not engaged in empirical work. Empirical work, the professor observed, can get you entangled (in other words, prove your Marxist theory wrong).

But what dogmatic adherents cannot risk, scientists must.

2.

I think that DT Cochrane has done some work on the triangle of differential accumulation, risk and activism. Perhaps he can contribute something to this exchange.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Nice chart. Here is my simplistic guess at what has happened since the 80s.

The causes you cite may affect the ‘real’ total return on the S&P 500. But how do they impact the correlation between the ‘real’ total return on the S&P 500 and the ‘real’ net assets of the top 0.01%?

The latter magnitude is determined by the portfolio of the top 0.01% and by the different ‘real’ returns on the various assets in that portfolio. As this portfolio changes, so will the correlation with the ‘real’ total return on the S&P 500. No?

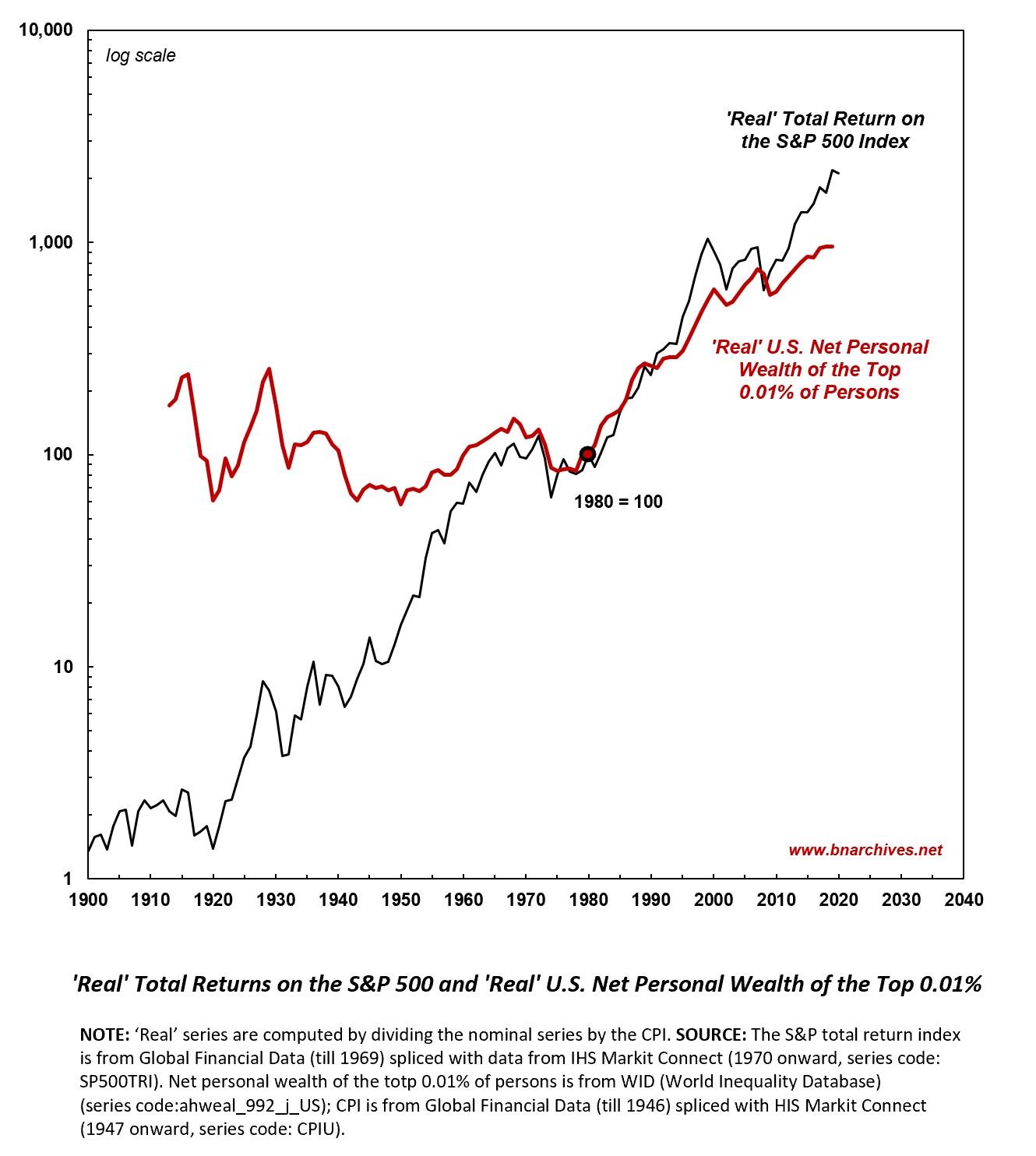

Here is a comparison between the ‘real’ total return on the S&P 500 index (market value + reinvested dividends deflated by the U.S. CPI) and the ‘real’ net wealth of the top 0.01% of persons in the U.S. (also deflated by the CPI).

We can see that the two indices go pretty much together from 1980 onward, but that prior to 1980 their movement was cyclically similar by very different in trend.

I doubt that the reason for these variations is that, prior to 1980, the top 0.01 of persons did not reinvest their dividends in something.

A more likely reason, I think, has to do with the way in which the portfolio the top 0.01% has been reallocated over the years. For example, if a relatively small portion of this portfolio was in equities till 1980, and if that portion rose dramatically since 1980, we would expect the correlation between the two series to increase, as it has.

Of course, these are just guesses. The answer requires a much closer look a the data.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Neat, James!

Would be nice to see both charts combined + detailed footnotes on sources since the series are surely spliced many times over.

November 28, 2020 at 4:05 pm in reply to: Can Capitalists Continue to Squeeze the Income Share of Employees? #4562Thank you James.

The answer to the question of what drives these two opposite trajectories and how these drivers relate to strategic sabotage is not self evident. Hopefully, someone will think it worthy of investigating.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Good questions, James.

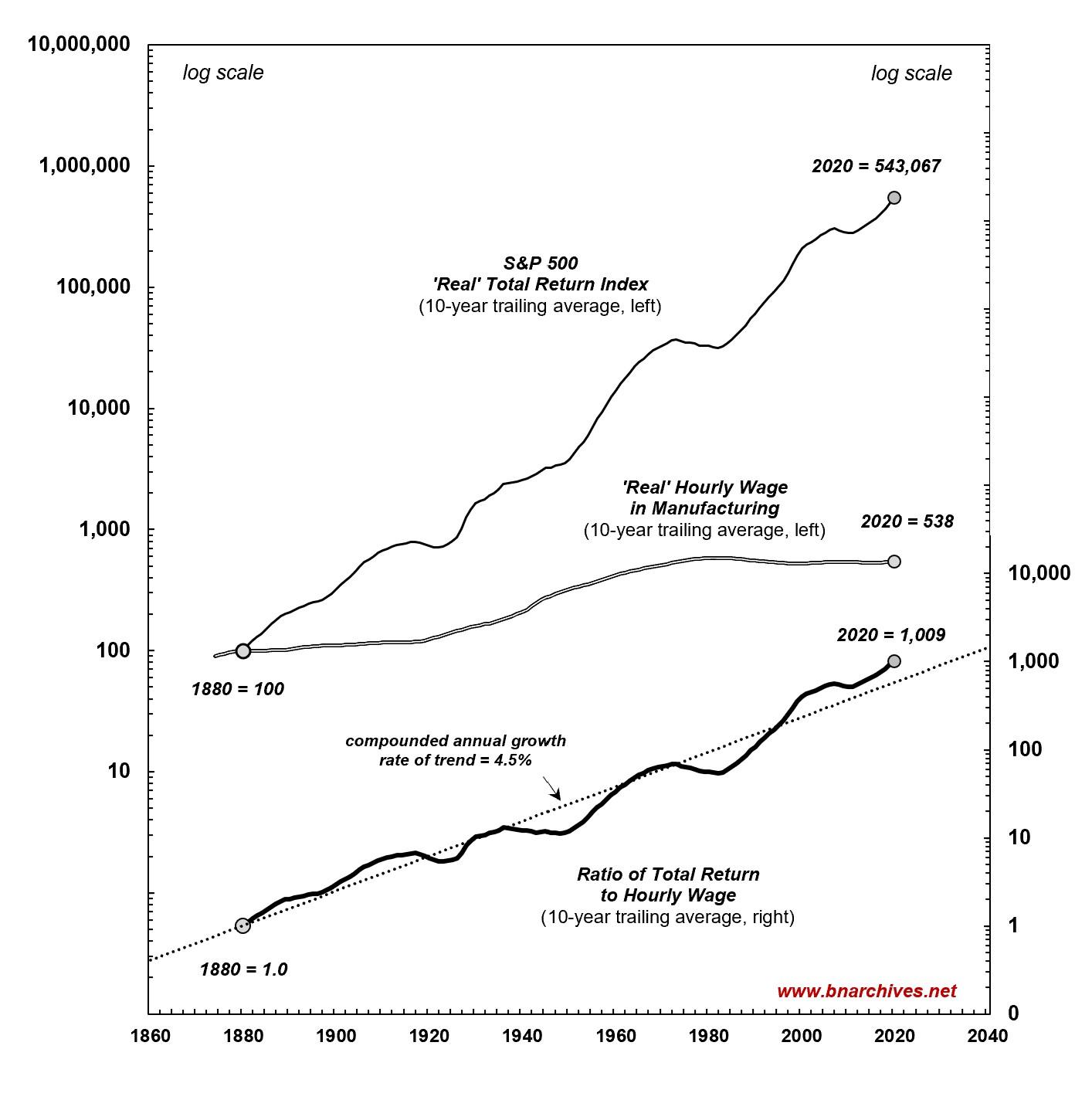

Our figure simply suggests that the vast majority of the population — i.e., those depending on labour income, small business income and state handouts — have gained little, and since the early 1980s, nothing, from the stock market’s glory. The stock market tide doesn’t lift all boats. It lifts only a tiny fraction of them. So while the business of America is business, most of its population is not in that business.

But then, probability notwithstanding, roughly half the U.S. population are made to believe that they are going to be rich; i.e., that some day they will ride the upper series instead of the lower one. That hope makes them admire those who are already rich. And that admiration makes them susceptible to stock market glorification.

I don’t know if that suffices as an explanation, but it flows.

Over the past 140 years, the total return on U.S. equities (capital appreciation plus reinvested dividends) grew 1,009 times faster than the manufacturing wage rate. Since the 1980s, the increase was due entirely to the rising stock market. Hourly wages, measured in ‘constant’ dollars, moved sideways.

In the United States, celebrating the stock market is celebrating the victory of the capitalist mode of power. The underlying population — made mostly of wage earners, small business people and those who are unemployed or not in the labour force — rarely if ever contests this celebration. This silence suggests something about the future of this society.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

The more you disaggregate, the greater the possibility of a discord of the kind you describe.

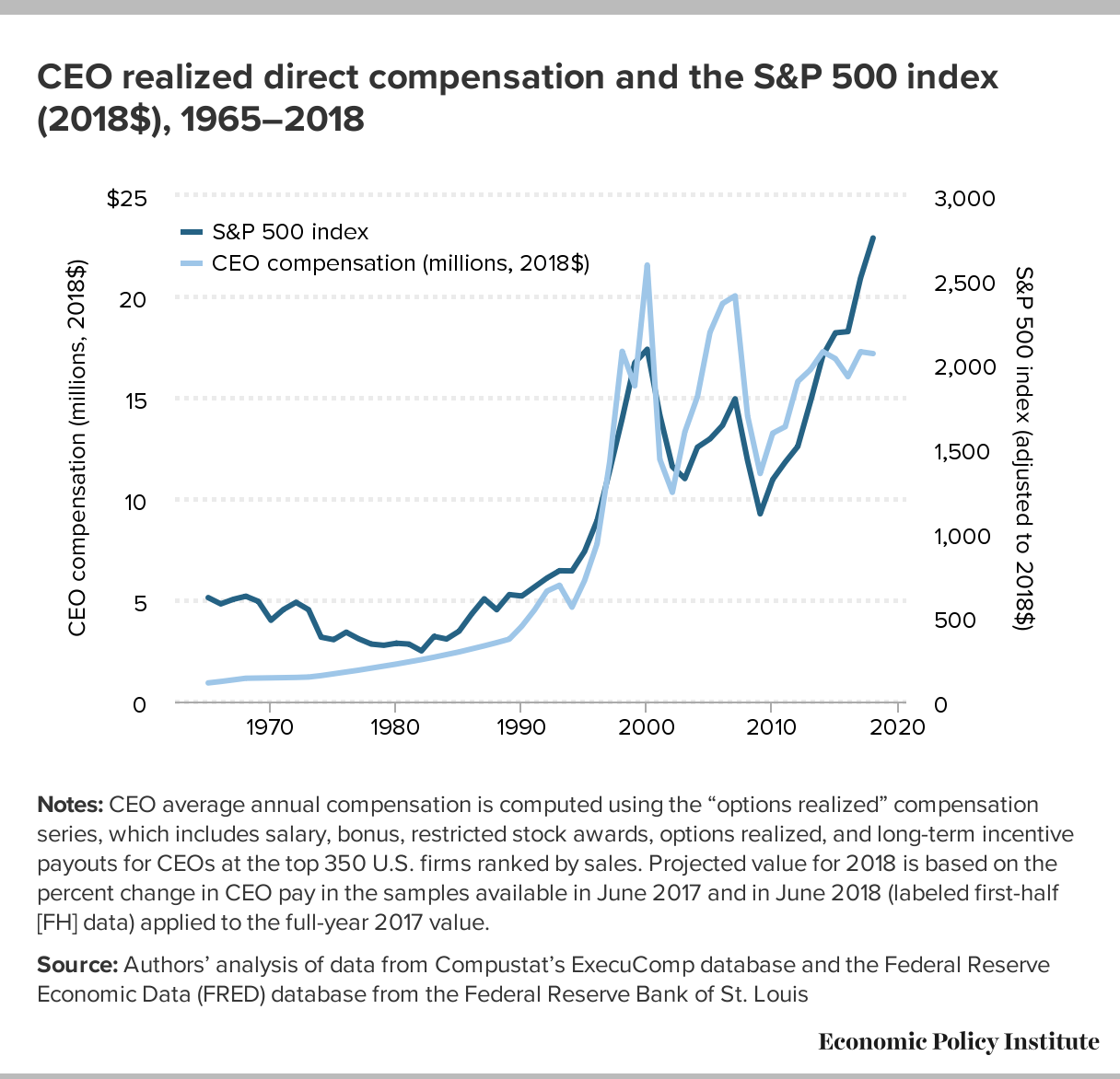

My point here is merely that the broad transformation of top managers into large owners brought their pecuniary interests in line with those of non-managing owners and greatly lessened the principal-agent problem.

This convergence within the ruling class doesn’t make things better to the vast majority of humanity. Possibly the opposite.

Much of the modern principal-agent debate can be traced to the 1932 work by Berle and Means on the ‘Modern Corporation and Private Property’. But since the 1980s, when top managers became large owners, the debate has cooled off. This chart, taken from a recent paper by the Economic Policy Institute, shows the tight correlation between CEO realized compensation and the stock market. Owners and top managers are no longer at odds.

Also, investors focus on total returns – namely, capital appreciation + dividends. Insofar as the two complement each other, the question of whether owners receive their earnings directly or have the corporation retain them is irrelevant to them. They don’t need the company’s dividends to buy other assets. They can simply sell the company’s stocks.

We can agree to disagree for now. And I’m always willing to be re-convinced.

November 19, 2020 at 7:18 pm in reply to: Intellectual property and the capitalist share of income #4512Thank you Blair and Yigal for drawing attention to this paper:

I read the article and admit to being baffled.

If I understand them correctly, Koh et al. make three related claims:

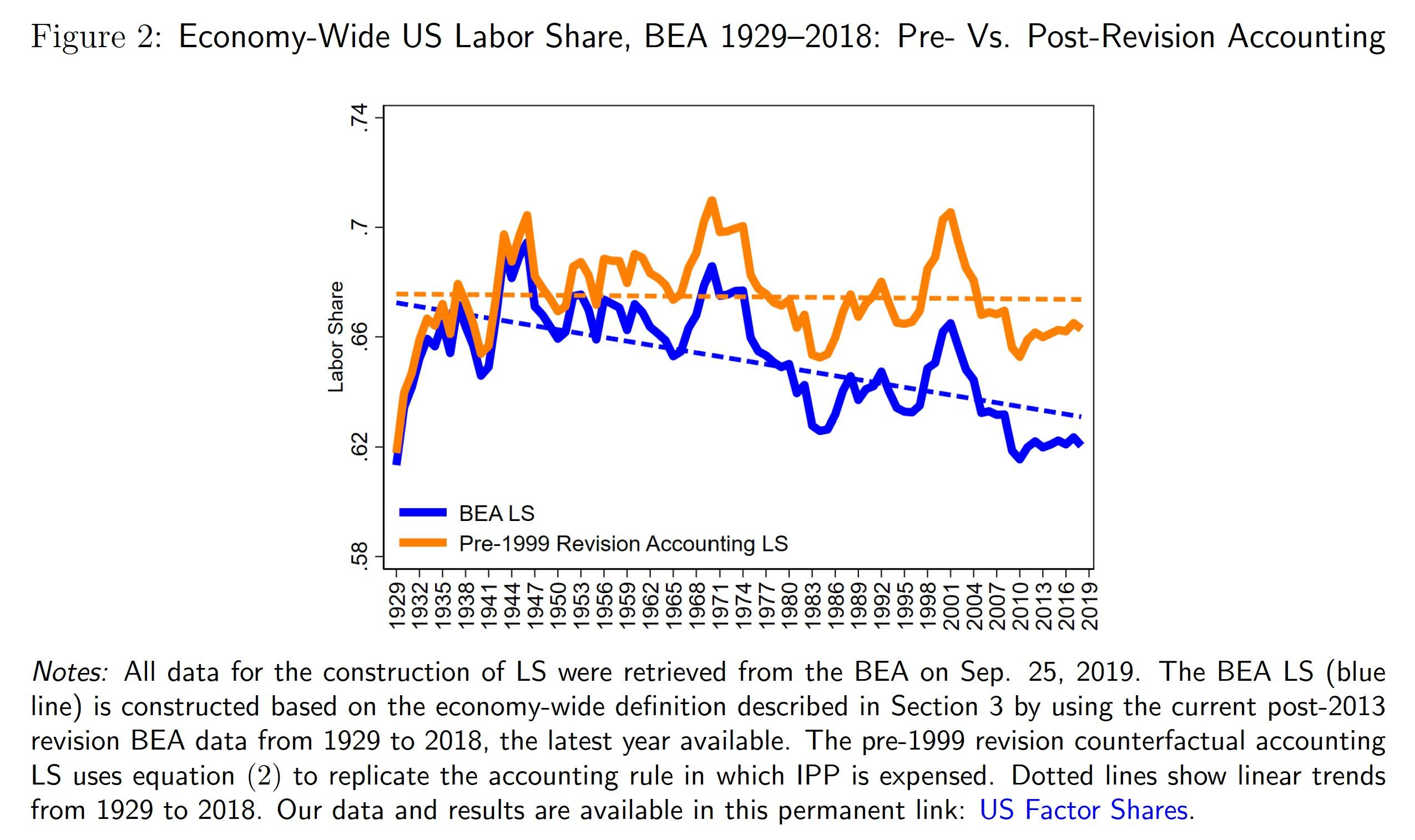

1. The BEA and other statistical services have been gradually reclassifying ‘in house’ production — i.e., production for the organization’s use rather than for sale — of software, R&D and artistic originals. Originally, these expenditures were treated as intermediate services (similar to a company spending on fixing its machines, or on manufacturing semi-finished goods). Having been reclassified, these expenditures are now treated as ‘property product investment’ and are classified as part of the gross investment category of the national accounts.

2. These new forms of gross investment, the authors say, increase the expenditure and income sides of GDP. On the expenditure side, they increase the magnitude of gross investment, while on the income side, they augment the overall magnitude of non-labour income.

3. This increase in non-labour income, they argue, is responsible for the historical downtrend in the labour share of national income (blue line in their chart below). But this downtrend, they imply, is artificial. It is merely the consequence of a change in accounting conventions (the reclassifying). If we ignore this reclassification, the labour share of national income shows no downtrend, as shown by the orange line:

What I failed to understand is why this reclassification should alter the magnitudes of GDP and national income in the first place.

As far as I can tell, prior to this reclassification, the ‘in house’ production of software, R&D and artistic originals was already recorded as part of GDP and gross national income. Its magnitude was estimated either by similar services being sold on the market, or by what it cost to produce, including wages & salaries, raw materials, interest, rent and profit.

So how is it possible for the mere reclassification of these already recorded intermediate expenditures as ‘investment’ to add to GDP and gross national income on the one hand and to generate the downtrend in the labour share of income on the other?

Are there any hidden imputations here that I have missed?

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

You start with the notion of hierarchy as a necessary evil (oppressive but efficient); you then say it is necessary (because autonomy is impossible); and finally you conclude it’s desirable (über alles). During this journey, injustice tends to diminish and eventually is assumed away as an issue. That’s how Carl Schmitt, a Nazi, could become the darling of many leftists and CasP the sweetheart of the post-liberal Right….

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Steve. A couple of small clarifications:

3. You are correct that the actual sale of an equity or a bond is a mere ownership swap against existing M-assets. But banks can meet demand for equities by increasing loans, and when these loans become deposits, the overall amount of M-assets increases.

4. My point here is that M-assets are not the only ‘means of payment’, so this is an insufficient reason to use only M-assets in money-based theorizing of inflation.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies