Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Jiang, Rong. 2008. Wolf Totem. Translated by Howard Goldblatt. New York: Penguin Press.

A semi-autobiographical novel about a Chinese student sent during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s to live as a herder in Inner Mongolia.

The broader context is the impact of population growth on the changing balance between agricultural and nomadic life and the inevitable destruction of the latter by the former.

The focus is the radically different worldviews of the two groups — the complex, long-term holistic perception of the nomads versus the one-dimensional, short-term emphasis on the farmers.

The main axis are the wolves: their pivotal role in regulating the ecology of the steppe, their impact on the consciousness and behaviour of both humans and animals, and their lasting imprint on the historical development of Mongolia and beyond.

Thrilling.

- This reply was modified 1 year, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 1 year, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

True — but (1) a significant part of this increase is due to input-price inflation, and (2) construction is roughly 4% of U.S. GDP, so its impact on the overall growth trend is limited.

The ‘external breadth’ of accumulation can be measured in different ways. Here are two simple figures to put the prospects of a new U.S. external breadth regime in historical context.

Figure 1 shows U.S. net private domestic investment as a share of GDP (gross investment less depreciation). Figure 2 contrasts this share with U.S. GDP growth.

Both series show long-term deceleration. They also don’t indicate recent upticks.

Here is the relation between the Petro-Core’s differential earnings, energy conflicts and the relative price of crude oil.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Pertaining to the second question, it would then seem that there is not much separating CaSP from say Marxist opposition to capital, other than the theoretical conception of the system, right? Beyond that, it seems you are both fighting the same cause.

Given that actual Marxist-informed regimes have tended to develop into dictatorships, I very much doubt that CasP and Marxists are ‘fighting the same cause’.

Dear Byron,

I don’t know how much you know about CasP, so my answers here are very general.

1) How does CaSP interpret headlines of S&P upgrades and credit ratings in general? Within the CaSP framework, what do these indicators mean, and what are their effects for the broader political economy, its population, businesses, and governments.

When I worked at the BCA Research Group, most editors dismissed the rating agency reports as lagging indicators: belated reflections of what the ‘market’ (read analysts and capitalists) has already expressed through the buying and selling of financial assets weeks and months earlier. I agree with this assessment, though I’d add that the rating agencies do serve a role: they offer a consensus benchmark for the ‘appropriate’ lending/borrowing premiums for different countries and companies. In generating this benchmark, though, the rating agencies – just like the capitalist organizations and governments they serve – are slaves to the capitalized worldview and rituals that CasP analyzes and criticizes. In this sense, the common bedeviling of these agencies as a discretionary imperial hand of the West is exaggerated if not totally misplaced in my view.

2) Does CaSP offer any new ways of acting within capitalism? Whether resisting it, or working with it, does CaSP offer new ways for the proletariat or businesses? Or does it only offer a better theoretical understanding of capitalism?

As advocates of human autonomy and voluntary collaboration, Shimshon and I resent power and sabotage as such. And as scientists, our research tells us that the effect of capitalized power on much of humanity and its environment tends to be negative and — because capitalized power knows no bounds — potentially disastrous (I use ‘tends to’ and ‘potentially’ because the issues here are never simple). For these reasons, we think capitalism should be changed and, if possible, replaced by a more autonomous and directly democratic human collaboration. And although we haven’t done much work on this subject ourselves, the very gist of CasP research indicates, by way of negation, what a better society might want to resist and move away from.

Form more on these issues, see our 2018 paper, ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’ https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

As a bonus, it would be nice to relate answers to other political economic theories (Marxism and Liberalism).

On the relation between CasP on the one hand and Marxism and liberalism on the other, see our 2023 piece: ‘The Capital As Power Approach. An Invited-then-Rejected Interview with Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan’ https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/799/

September 30, 2023 at 7:12 pm in reply to: Mark, Engels, and Public/Private Credit as Power Index Precursor #249804Nice be so highly graded, if only among the non-sequiturers!

September 28, 2023 at 7:48 pm in reply to: Mark, Engels, and Public/Private Credit as Power Index Precursor #249800The tail that wags the dog?

The accumulation of ‘actual’ capital is counted in backward-looking labour time, while the confidence of the accumulators relies on the forward-looking ‘fiction’ of credit (or the other way around). Adhering to this house of mirrors keep Marxists stuck in no-man’s land….

- This reply was modified 2 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

1. It would be nice to offer solutions, but first we need to convince our audience there is a problem. We have been trying to do so for over 40 years, and truth be told, it seems that we don’t even have an audience…. For example, our 2022 Hebrew book, Capital and its Crisis, received a grand total of zero reviews. We continue to research and publish regardless; but our ability to influence the course of history seems rather limited.

2. On a more positive note, have a look at our 2018 paper, ‘The CasP Project: Past, Present, Future‘. Section III: Future, suggests seven research trajectories. Pursuing them might help construct a better world (if you prefer watching, here is the video).

3. And then, there is the younger generation of brilliant CasPers, whose research is almost always impressive and occasionally mind boggling. A lot of promise there, or so I hope!

- This reply was modified 2 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

With respect, I feel CasP is failing of its own radical promise and insights if it does not arrive at the full conclusion that the untrue “representations” – they are actually prescriptions not representations – of money, finance, capital with respect to reality and as calculations for the manipulation of reality ought to be wholly and radically abolished […] The complete abolition of capital and capitalism is an existential necessity, [etc.]

1. Yes, I agree. Capitalism should be radically transformed and, if possible, replaced by a different, saner from of social organization. But you don’t need CasP to draw this conclusion. Marxists, anarchists and many social democrats hold similar views.

2. CasP’s main contribution is to show that capital is power, and that capitalism is a mode of power. But I don’t think these claims per se are enough to assess the pros and cons of capitalized power. Such assessment requires that we figure out, both theoretically and empirically, exactly how, to what extent and with what consequences capital is power and capitalism a mode of power. In my view, this research remains very much in its infancy.

3. These uncertainties do not mean we should not try to change or abolish capitalism. The very imposition of capitalized power and its assorted forms of sabotage is good enough reason to jettison it, even if it doesn’t terminate humanity. But I think we should be careful not to deduce our preferences from ‘CasP findings’. Regrettably, these findings, however promising, require more breadth and depth to replace the existing ideologies and critiques of capitalism.

4. I’m voicing these reservations not to diminish CasP, but to defend it. I think CasP is a very effective template for analyzing — and ultimately changing — capitalism. It helps avoid the difficulties and impossibilities of Marxist materialism and neoclassical utilitarianism while offering insights into crucial processes they serve to hide. But these advantages hinge on keeping CasP a vibrant, open science. Once CasP starts accumulating preset ‘positions’, ‘assertions’, ‘leaders’ and ‘followers’, its science and novelty will fizzle out and dogma will take over.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

This all asks the question. To survive, must we fully envision the abolition of income-producing private property and of money, markets, capital and finance? If not, what is envisaged and/or advocated from a Capital as Power perspective?

As I see it, the capital as power approach argues that (1) capital is best understood as the quantification of organized power; and (2) this understanding alters the way we theorize, historicize, research and relate to capitalism in practice.

I think that the practical implications of this understanding — namely, whether to defend, reform or abolish capitalism — are open ended. These implications are influenced by the notion that capital is power, but that notion alone does not chart the path forward. For example, CasP anarchists might prefer a system that minimizes organized power; disillusioned neoliberals might argue that the best defense against the quest for power is invigorating capitalist competition; while CasP fascists might go for centralized state and racial power instead.

A side note. The chief capitalist quantities are those used for the creordering of power. But I think that quantities will remain necessary in any complex society, even egalitarian ones. It is difficult if not impossible to juggle the balls of complexity without them.

Thank you Brian. I don’t know if the wranglings you describe represent a new cold war, but I can offer some relevant CasP pointers.

Begin with Blair Fix’s 2020 paper ‘Why America Won’t Be Great Again’, in which he compares the differential energy use per capital of the ‘West’ relative to the ‘East’ and of the U.K., the U.S. and China relative to the world. Here are the U.S. and China charts from his paper.

Next is our own 2019 Real-World Economics Review paper, ‘Making America Great Again’, in which we assessed Donald Trump’s aspirations to stop the rise of China. One of the figures in that paper showed the growing long-term reliance of U.S. corporations on profit from foreign sources. This chart is updated here till 2022.

https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/630/

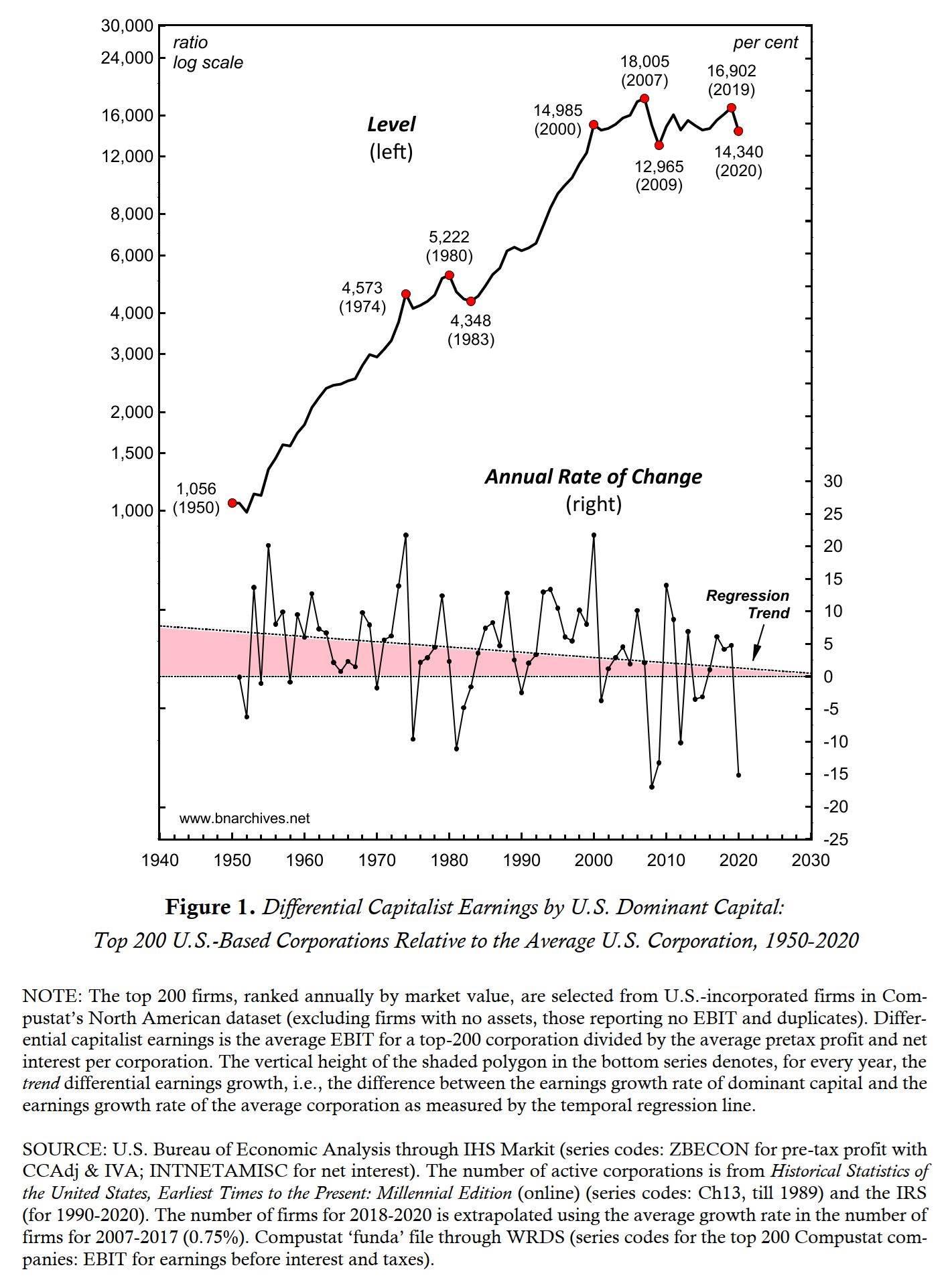

A third relevant paper is our 2021 Real-World Economics Review Blog post, ‘Dominant Capital and the Government’, which assesses the relative power of these two entities in the U.S. (though note that they are deeply intertwined). This chart shows the changing level and rate of change of differential earnings (EBIT) of the 200 biggest U.S.-incoporated firms.

https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/716/

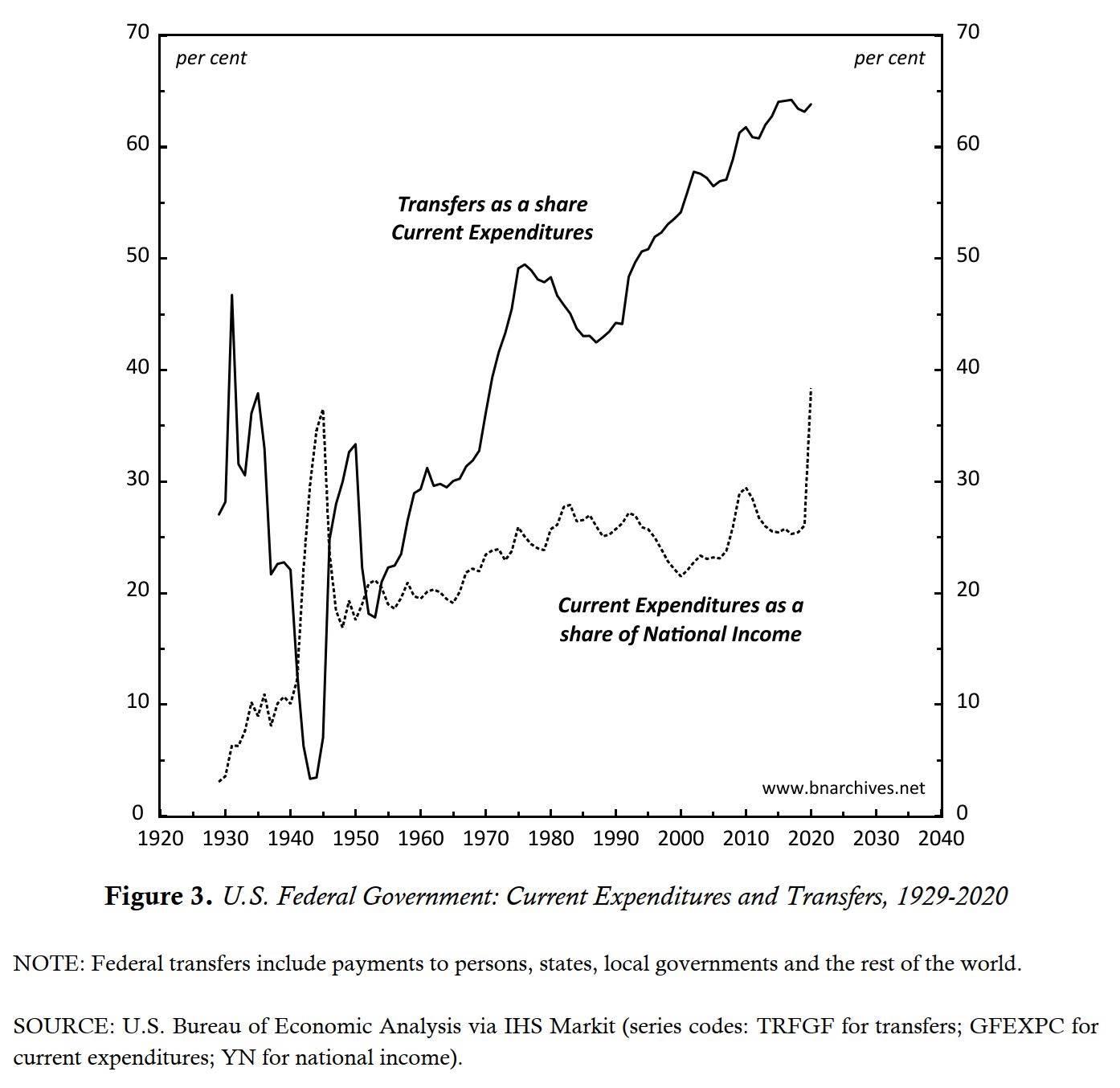

The following figure, from the same paper, shows the U.S. GDP share of Federal government expenditures and the rising proportion of those expenditures earmarked as transfers. U.S. policymakers these days have very little spending discretion.

The final paper in this short list is Christopher Mouré’s ‘Technological Change and Strategic Sabotage: A Capital as Power Analysis of the US Semiconductor Business’, published in 2023 by Real-World Economics Review. The article goes into the intricacies of strategic sabotage and how manipulated ‘shortages’ affect the differential profits of dominant capital in this sector. This chart exhibits one of those links.

https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/777/

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Interesting chart, Adam.

The negative correlation between falling differential capitalization of fracking firms and rising of anti-fracking sentiment raises the question of what exactly the public sentiment affects: differential earning, differential hype, or differential risk?

One way of answering this question, however tentatively, is to examine differential PE (fracking PE relative to S&P500 PE). This ratio removes the effect on differential capitalization of differential profit, leaving us with the ratio of differential hype to differential risk.

Granted, this is only a makeshift decomposition, since capitalization usually reflects future rather than preset profit; but still, it might be an interesting thing to examine.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

This chart from our 2002 Global Political Economy of Israel shows the tight correlation between the Israeli growth rates of population and per capita ‘real’ GDP.

Is this positive correlation the international norm? And if it is the norm, will global demographic deceleration amplify economic stagnation?

So far, the capitalist mode of power has been associated with a growing population, which raises the question of what will happen to this mode of power if the size of humanity stagnates or even falls.

I don’t know the answer to this question, but I do know (1) that prior modes of power existed with stable or only gradually rising population, and (2) that capitalism has been rather agile in responding and adapting to changing circumstances.

Humanity’s cumulative impact on the biosphere makes population de-growth likely, if not inevitable: this de-growth will come either through deliberate or semi-deliberate human action, or courtesy of a socio-ecological calamity.

Regarding the consequent prospects for capitalism, the obvious question to consider are: (1) what are the effects on capitalist power relations of population growth/decline; and (2) what capitalist organizations can do to alter these relations when populations start to stagnate or contract.

A new CasP research project in the making?

- This reply was modified 2 years, 11 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies