Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Thank you, James. The 602-page doorstopper is on its way to the bookstores, though, for some reason, the publisher’s book page isn’t up yet.

The book presents and situates CasP theory and research — our own as well as that of others — within the broader evolution of political economy. Some of this material has already appeared in English, but much of it hasn’t, so a translation would be nice. Whether we will do it is another matter….

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

In his interesting 2010 book, Misplaced Generosity. Extraordinary Profits in Alberta’s Oil and Gas Industry (Edmonton, Alberta: Parkland Institute, University of Alberta), Reagan Boychuk offers an account of Alberta’s oil and gas revenues, costs and profit, plus imputations of ‘normal’ and ‘excess profit’. (Twitter thread)

The computations/imputations are built from the bottom up – i.e., they are based on estimates of the industry’s output, average oil/gas selling prices and investment and production cost, so, on the face of it, they reflect the business performance of Alberta’s oil and gas industry — and nothing else.

But here is a question: output levels are collected at the provincial levels, as are selling prices (I assume). But capital and operating costs probably come from the companies themselves, and since these companies are often large transnationals rather than Albertan only, it is hard to know the extent to which their data reflect local operations ‘uncontaminated’ by transfer pricing.

Regarding my point (2) above, here are the weekly data for deposits and credit in the U.S. banking system — first in levels ($bn) and then in annual rates of change (%).

Loans and deposits do move in tandem.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Conceputally, NIPA profits are attributed to ‘industries’, so ostensibly you can select the sectors that produce ‘capital goods’ and aggregate their profits.

Practically, though, NIPA profits are derived from corporate reports, and since many corporations today operate in more than one sector (and often in many), it is difficult if not impossible to know what profits come from what sector.

As far as I know, the national accounting rule of thumb is to attribute the company’s entire profit to the sector that generates most of its sales, but if this largest sector accounts for only 20% or 30% of the corporation’s operations, the results can be very misleading.

November 10, 2022 at 7:48 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248575November 10, 2022 at 1:01 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248571Thank you for both posts, Scot.

In our book Capital as Power, we describe the ever-growing terrain of capitalization:

Nowadays, every expected income stream is a fair candidate for capitalization. And since income streams are generated by social entities, processes, organizations and institutions, we end up with the ‘capitalization of every thing’. Capitalists routinely discount human life, including its genetic code and social habits; they discount organized institutions from education and entertainment to religion and the law; they discount voluntary social networks; they discount urban violence, civil war and international conflict; they even discount the environmental future of humanity. Nothing seems to escape the piercing eye of capitalization: if it generates earning expectations it must have a price, and the algorithm that gives future earnings a price is capitalization. (158)

Extrapolating the foregoing illustrations, we can say that in capitalism most social processes are capitalized, directly or indirectly. Every process – whether focused on the individual, societal or ecological levels – impacts the level and pattern of capitalist earnings. And when earnings get capitalized, the processes that underlie them get integrated into the numerical architecture of capital. Moreover, no matter how varied the underlying processes, their integration is always uniform: capitalization, by its very nature, converts and reduces qualitatively different aspects of social life into universal quantities of money prices. In this way, individual ‘preferences’ and the human genome, the structure of persuasion and the use of force, the legal structure and the social impact of the environment – are qualitatively incomparable yet quantitatively comparable. The capitalist nomos gives every one of them a present value denominated in dollars and cents, and prices are always commensurate. (166)

With this being said, I think we need to distinguish ‘actual capitalization’ from ‘as-if capitalization’.

As Ulf Martin explains, capitalization is an ‘operational symbol’ – namely, a symbol that does not simply represent the reality, but explicitly defines and creates it in the first place. And, to me, this feature suggests that for something to be labeled capitalization, it needs to be consciously articulated as such.

In this context, we can think of ‘actual capitalization’ as one that the capitalizer explicitly spells out; as-if capitalization as one that the outside observer-theorist imposes; and in-between cases as weighed by their proximity to either pole.

A wage payment in this scheme is actual capitalization if the capitalists and workers involved calculate it as such, but it is only as-if capitalization if the idea is merely imposed by the outside observer-theorist.

And in my opinion, the same goes for discoveries of ‘ancient capitalization’: unless we can demonstrate that the price was consciously or at least explicitly articulated by the price setter as the discounting of expected further earnings, it remains a retrospective, as-if imposition.

***

Martin, Ulf. 2019. The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery. Review of Capital as Power 1 (4, May): 1-30.

What does the harnessing of matter and energy tell us about the history of humanity?

1. Consider the following chart, taken for our paper ‘Growing Through Sabotage’, and assume that the numbers it shows are correct. Do these numbers tell us anything about the social formations of families, tribes, chieftainships and states? About slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism and fascism? About where society is likely to be on the spectrum between direct democracy and tyranny? Energy and matter create an ‘envelope of the possible’: the more energy and matter being converted, the more energy and matter are available for use. But the quantities that end up being used and the purpose for which they are used remain open-ended.

2. In capitalism, the important quantities are not material/energetic, but pecuniary, and pecuniary magnitudes are the product of both quantities and price. This fact means that, with different prices, the same material/energetic quantity can give rise to different pecuniary magnitudes (see the enclosed chart from Blair Fix’s paper, ‘The Truth About Inflation’, showing the range of price changes associated with a given rate of inflation). And since relative prices are a matter of power, so are the pecuniary magnitudes they give rise to.

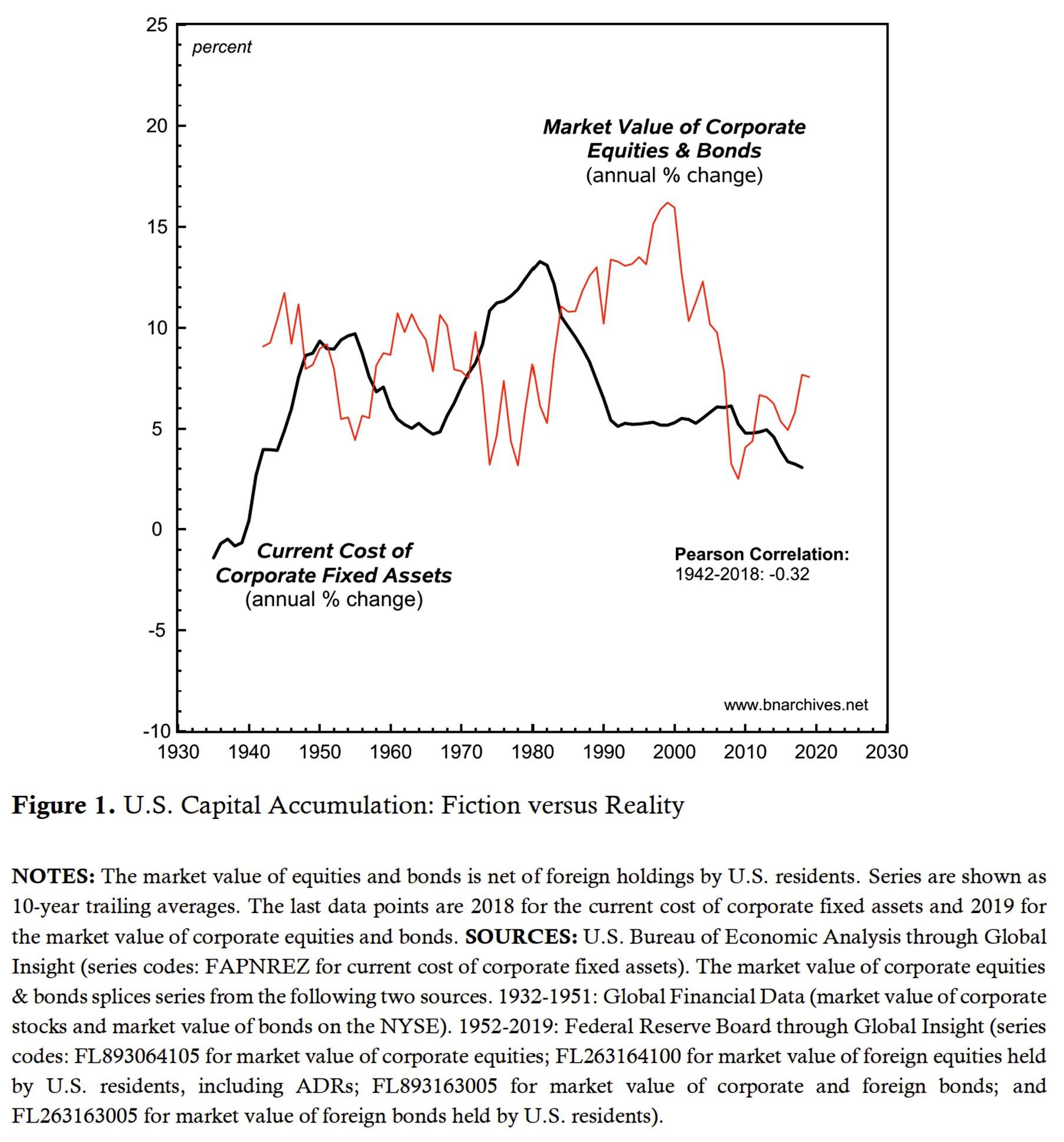

3. On its own, the fact that capitalism creates more backward-looking ‘capital goods’ counted in terms of energy/matter/labour time tells us little about the forward-looking accumulation of ‘capital’ which discounts risk adjusted expected future earnings (not to speak about their differential magnitudes). The chart below, taken from our rejected interview, ‘The Capital as Power Approach’, shows that, in the United States, the growth of these two magnitudes are inversely correlated. In other words, the two ‘accumulations’ — the one dear to economists and the other that matters to capitalists — are opposite in their direction, and labelling the former ‘real’ and the latter ‘fictitious’ does nothing to make this problem go away.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

(1) Let’s tell a simple parable. In this parable there are two separate groups of 100 people each, called ‘industry’ and ‘business’.

(2) Industry is characterized by two features: (1) its members deliberate/cooperate/act autonomously and democratically to determine both their goals and the most effective ways and means of achieving those goals; and (2) their goals concern not only their output, but also — if not more so — the very processes of producing this output and developing themselves and the institutions that participate in this production.

(3) The purpose of the business group is to control industry and use this control to extract income from it. The effect of business on industry can be positive, nil or negative. However, if the impact is positive, and if industry endorses and applies it, then business is no longer separate from industry, but part and parcel of it. And since business becomes part of industry and no longer controls it, it cannot extract any income from it. By contrast, if the effect of business on industry is nil or negative, industry — assuming it is autonomous – is likely to reject it. In this case, the only way for business to have the last say, is by enforcing this impact – i.e., by ‘sabotaging’ industry.

(4) If we accept this parable as a way of thinking about actual capitalism, it follows that the industry-business distinction holds only when business sabotages industry. And this condition means that the only thing that business can do is calibrate the nature and intensity of industrial activity by setting sabotage somewhere between none (full industrial capacity shown the rightmost point on Figure 1) and total (zero industrial capacity shown by the leftmost point in Figure 1). According to our parable, though, this calibration contributes nothing to industry; it merely allows it greater or lesser freedom to act in the best the interest of humanity.

(5) And now to your question, Corentin:

[W]hat are advertisements, fashion, sales representatives, etc. for if not to forge new needs and stimulate consumption, hence industry?

Our answer: advertisement, fashion, sales representatives, etc. contribute not to industry, but to the business control of industry. An autonomous society decides for itself, democratically, what to do and how. It has no need for business stimulation, advertisement and the creation of ‘new needs’. If we are ever to see such society emerging, it will likely move away from the sabotage that business relentlessly imposes and glorifies (private transportation, urban sprawl, fast food, conspicuous consumption, brainwashing, poisonous production, etc.), as well as scale back the enormous waste of sustaining and fortifying the power hierarchies that business uses to control us all.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

November 2, 2022 at 8:06 am in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248518Bagnall’s text is intended for the specialist, and I find it really hard to follow. I do understand, though, that:

1. The discussion involves fragmented ancient evidence that the experts piece together, fill the in-between blanks and then interpret the results as if they were modern financial transactions.

2. The transactions involved aren’t purely monetary, but hybrids of money and ‘in-kind’ flows. This mix means that even when the transactions are clearly stated — and most aren’t — their underlying magnitudes are only partly specified:

We can now summarize the types of transactions involved in the Tetoueis documents and the new Berlin text: (1) loans in kind to be repaid in kind with interest of 50 per cent ;20 (2) loans in money to be repaid in kind, with both amounts specified but not the interest; (3) loans in money, amount specified, to be repaid in kind at a price not specified but reduced by a third; (4) loans in money, with amount not specified, to be repaid with a fixed amount of produce. (Bagnall: 93)

With this in mind, interpreting the ‘pricing’ of these contracts as if they were acts of capitalization, however embryonic, seems to me far fetched.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

This is the reason I wonder if there are some key texts you could name as central in building your understanding to the point that CasP became conceivable, derivable to yourself and Shimshon Bichler?

The books that have influenced us are referred to in our works, but I don’t think the ‘secret’ is in what you read: from our experience, the pivot is actual research. It is research that raises the simple questions that nobody seemed to have raised before, that leads you to question what the experts believe, that opens your horizons to totally new spaces, entities and processes. And it is research that directs you to search for forgotten writings and helps you weave them into a new understanding of the world.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Thank you Rowan.

“… a notion of capital as capitalization & capitalization the product of a power relations makes it by definition nondeterministic & contingent, I think, in ways old capital theories wouldn’t have been. Which is to B&N’s credit, but to the detriment of “capital theory” as a project.”

Neoclassical theory and its economic offshoots are ‘deterministic’ only on paper. In practice, their inner arguments cannot be operationalized (utility and util-denominated productivity are mirages) and their indirect ‘testing’ almost always fails (generating a multiples ‘measures of ignorance’ compensated for by an even greater number of ‘distortions’).

CasP’s argues that the trajectory of capitalist societies reflects the capitalist creordering of power against opposition. The capitalist attempt to creorder society, being subjugated to the ritual of differential capitalization, is relatively simple to articulate and often possible to predict. Resistance to this creordering, however, can be open-ended, which makes it difficult to map and anticipate. One way or the other, the resulting clash between these two moments is complex and non-linear, which means that we can only say so much about its immediate results and even less about its future outcomes.

With this limitations in mind, CasP research has managed to map a growing number of historical power patterns related to stagflation, M&As, energy use and hierarchy, wars, societal U-turns, military spending, risk reduction, popular culture, sabotage, consumption, debt, high-technology, etc. And what’s more, it demonstrated that some of these patterns continue to hold beyond the time period for which they were originally mapped and theorized. Not bad for a non-deterministic science of society.

My feeling about CasP is that it remains on-track but an incomplete project.

The idea that capital is power and that capitalism is a mode of power is just a theoretical shell. It has to be concretized, and this process has barely begun.

[CasP] theory is difficult. When empirically supported theory is complex and difficult the public prefer a simple lie. This is one reason why capitalism works so well. “Supply and demand” is repeated like a catechism: a self-evident truth to everyone.

The theory of demand and supply may be based on a lie, but it’s anything but simple. Most economics students don’t really understand it, and most non-economists cannot decipher a single paragraph of a neoclassical paper. By comparison, CasP is readily accessible and can be understood by any intelligent person who puts her/his mind to it.

The reason why neoclassicism reigns and CasP ignored has to do with the monopoly economists hold over all things ‘economic’, not the simplicity of their arguments.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

October 13, 2022 at 7:07 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248446Thank you Scot.

I read Chapter 2 in Tan’s book, ‘The Use and Abuse of Tax Farming’, and found it really interesting. What I didn’t find, though, is any evidence that tax farmers discounted future earnings — in Rome and elsewhere.

In your post, you write that

Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on.

Well, from Ch. 2 in Tan’s book it seems that historians of tax farming know relatively little, if anything, about the profitability of tax farmers. One guesstimate puts the rate of profit of Roman publicani in a certain region between 8-215%, while another speculates it was 30% (pp. 57-8). But no one really knows.

Similarly, judging by this chapter, nobody knows what calculations contract bidding was based on. The chapter does not mention discounting/capitalization of future earnings, let alone offers any evidence that such discounting/capitalization took place.

Reading between Tan’s lines, my impression (again, nobody really knows) is that contract bidding was largely a matter of arms wrestling. When the tax farmers overcame their mutual disdain and acted in unison, prices were low and they could make a bundle; when they bickered, prices were high and they earned little or even lost (and sometimes demanded retroactive rebates, no less). There was no need for any risk coefficients and raising the normal rate of return to the power of five. It was simply a matter of strongmen groping for what the ‘Republic will bear’.

This isn’t an area I know enough about, and there may be other studies where discounting of tax farming is discussed and assessed. But without such evidence, the claim that these contracts reflected discounting seems to me unsubstantiated.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

October 12, 2022 at 3:57 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248441Let’s leave Sumer aside.

Did capitalization — not interest or other future payments, which, on their own do not imply capitalization — start in Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic? Is this where the 13-14th Century European burgers picked the idea from?

That would be an interesting study to read.

October 12, 2022 at 6:04 am in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248436It seems to me that, with a sufficiently large sample, writing is a good indication for thinking.

Modern financial textbooks and highly-paid forecasters tell the future by combining expected earnings, assessments of risk and notions of normality. And the fact that capitalists bet on these written forecasts with their money suggests they do believe in what they pay for. Of course, these expensive forecasts, pronounced with stern faces and associated probabilities and aggregated into fancy publications such as consensus forecasts, are almost always wrong. But the reason they are wrong, claim the forecasters, is not that the future is unknowable, but that human beings refuse to obey the rational scriptures and end up walking randomly. But not to worry. There is now a new, innovative profession, formalized by straight-face behavioural financiers, that is busy predicting the external irrationality of us mortals in order to make the future whole again (think Ulf Martin’s autocatalytic sprawl).

Of course, we can never know for sure, but it seems to me that the ontology of the Sumerians, whose gods created humans to be their slaves, whose Anu was supreme authority and Enlil turbulence at will, whose ironclad rate of interest was religiously sanctified, and whose military conflicts were won and lost by competing gods, was very different.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

October 11, 2022 at 7:26 pm in reply to: Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value? #248429One of my graduate students in ‘Seven Lectures on Capital’, a course I taught at the Economics Department in Tel Aviv University many years ago, told me that “paleolithic individuals” (his term), just like present-day utility hunters at the shopping mall, made choices by subjecting their indifference maps to budget constraints. I kid you not.

Or, a recent simulation of the evolutionary origin of hierarchy argues that biological networks, from the level of organic molecules and up, become hierarchical only in the presence of what the authors call ‘connection costs’. When there are no connection costs, claim the authors, these networks tend to develop flat structures (Mengistu et al. 2016). In other words, molecules, single-cell organisms and herds of mammals are just like the capitalists who own McDonald’s: they all self-organize to minimize their transaction costs in their quest for maximum gain.

With this in mind, should we trace the origins of capitalization back to Sumer? In my view, the answer is no:

- One of the distinguishing features of the capitalist mode of power is that power appears as a universal quantitative relationship between entities (relative prices). This feature first emerged in the early the European Bourgs and was later formalized by Johannes Kepler to describe the forces of the cosmos. In Sumer, powers (in plural) were stand-alone qualities. The idea that power was a universal quantitative relationship between entities was inconceivable.

- The “larger use of credit”, as Veblen called it, also a key feature of the capitalist mode of power, presupposes the growing universality of the price system. This condition did not exist in Sumer.

- Forward-looking capitalization is a derivative of the larger use of credit, again, inconceivable in Sumer

- Differential capitalization emerges from the wider use of capitalization, unimaginable in Sumer.

Of course, if you can show that these observations are false, or that tracing capitalization back to Sumer is indeed useful and revealing, I’ll withdraw these contestations.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies