Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

Sometimes, it helps people to sacrifice precision for clarity.

Very true, but, in this case, I think you oversimplify. In your explanation you write that, ‘The assumption is that the firm can maintain the same rate of profitability as it grows.” This assumption may be correct in the case of expanding internal breadth (M&A), when no new capacity is created. But when firms expand through external breadth (greenfield), the assumption that profitability will remain constant is often false. Indeed, the key threat of greenfield is that it undermines corporate coordination, reduces pricing power, and compresses markups and profitability. This is one of the reasons why firms have drifted away from greenfield in favour of M&A.

[…] true precision would require adding a third axis to the differential accumulation model that accounts for corporate debt, which is another way to affect the expected effective annualized return (aka discount rate)

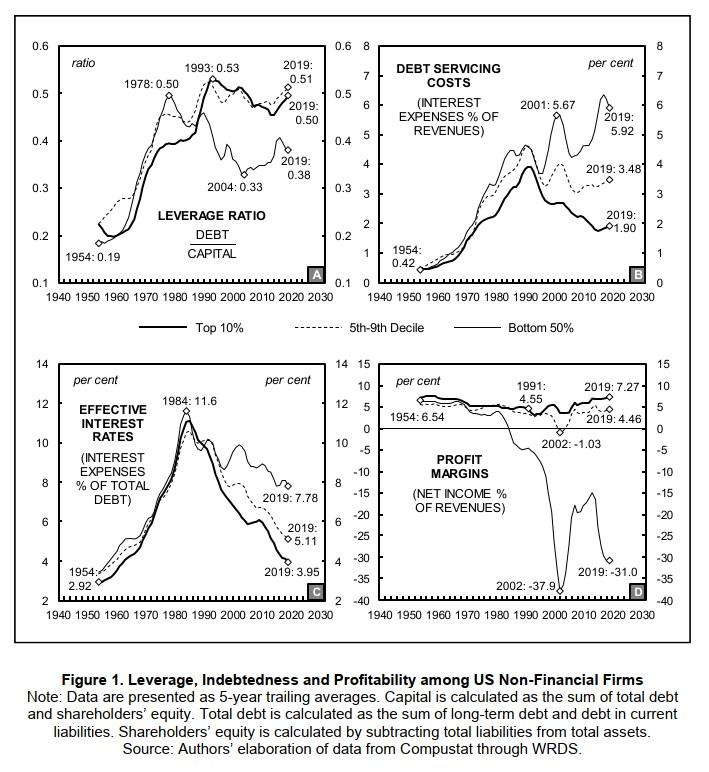

You are correct again — the cost of debt is very important. But I believe that this cost is already included in internal differential depth (differential cost cutting). For more, see the recent work of Baines and Hager, where they examine, among other things, differential interest costs.

Baines, Joseph, and Sandy Brian Hager. 2021. The Great Debt Divergence and its Implications for the Covid-19 Crisis: Mapping Corporate Leverage as Power. New Political Economy (OnlineFirst, January 6): 1-17.

The assumption is that the firm can maintain the same rate of profitability as it grows, so increasing the size of a firm should lead to increasing the accumulated profits (and increased market share). If the firm increases its size faster than average, then it will achieve positive differential accumulation.

To be precise:

1. For an increase in differential breadth to raise differential profit, the only condition is that differential depth does not decline (% wise) by more than the % increase in differential breadth.

2. Changes in market share (% of aggregate universe sales) do not have a one-to-one mapping with differential profit.

Define:

1. differential breadth = differential employment per firm

2. differential depth = differential profit per employee

Then expand the following truism:

3. differential profit per firm = differential profit per firm

= (differential profit per firm / differential employment per firm) x differential employment per firm

= differential profit per employee x differential employment per firm

= differential depth x differential breadth

As they stand, equations 1, 2 and 3 hold independently of the level of production.

***

To your question: firms will seek to raise their differential breadth if they anticipate the increase will not lower their differential depth by more, and this assessment will be affected by what happens to production, as well as numerous other considerations.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

March 11, 2022 at 3:58 pm in reply to: Did Capitalism Change the Nature of Power, or Just Its Expression? #247870Here is the pound price of gold relative to other UK prices.

Is this price the same as gold’s value? If yes, why is this value changing? If no, what is this value?

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 10, 2022 at 11:04 am in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247791Do you see any contradiction in claiming, within the same breath, that (1) you’ve outlined “one possible way to resist” and (2) your “possible” way “is probably impossible to plan”?

I believe you are misquoting me. What I wrote was that “this type of systemic change is probably impossible to plan more than one or two steps ahead of time.”

Over the past millennium, the world has seen two major systemic changes: the first, from feudal/autocratic systems to capitalism; the second, from capitalism to state communism (one might argue that the shift from state communism to capitalism marks a third instance — though here the alternative was already present). These changes were largely unplanned.

Conceptually, systemic transitions have two components. (1) the imagined goals of those who seek change and those who try to prevent it; and (2) the actual conflictual process of transitioning from the old regime to the new. In practice, the two components are deeply intertwined and tend to impact each other in complex and often unpredictable ways. This is why I doubt that systemic changes can be planned more than one or two steps ahead of time.

What can be done ahead of time is to analyze the existing system to understand its strength and weaknesses and to determine, as much as possible, what parts of it are desirable and what aren’t — with the explicit recognition that these analyses are tentative and will likely be modified.

Finally, and importantly, I think that analyzing an existing system, however critically, lends only limited insights into what should and could replace it. When you criticize an existing system, you dissect what is. When you conceive/build an alternative system, you create something new. And, for the most part, the act of creating a new social order — particularly when this creation is conflictual and complex — cannot be easily deduced, if at all, from the analysis of the old.

In my view, this conflictual act of creation is the main reason why ‘Marxist praxis’ has had little to do with Marxist analyses of capitalism, and it is also the reason why CasP theory per se can tell us very little about autonomy and direct democracy, let alone how to get there.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 9, 2022 at 11:20 pm in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247788I am not sure how you get from “capital is power” to “stock market crash good.” Seeking to understand capital as a mode of power does not require animosity towards power. Indeed, one of the knocks on CasP is that CasP doesn’t attempt to suggest to us what can/should be done with its conclusions; i.e., CasP lacks praxis. See, Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

Scot’s interpretation differ from Shimshon’s and mine.

We oppose modes of power in general and the capitalist mode of power in particular. The purpose of our research is to understand the capitalist mode of power in order to change it and, if possible, move away from it. I think other CasP researchers share a similar sentiment. Shimshon and I support autonomous, direct democracy, even though this type of society seems far-fetched at the moment and difficult to achieve. The last section of our article ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’ outlines one possible way to resist and begin to move away the capitalist mode of power — though this type of systemic change is probably impossible to plan more than one or two steps ahead of time.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

February 8, 2022 at 7:00 pm in reply to: Correlation between capacity utilization and markup #247756It is worth noting that in most cases ‘capacity’ measures refer to the maximum volume that businesses think they can produce profitably. In a minority of cases, when business surveys are not available, the statisticians simply connect production peaks and interpret the interpolation (or extrapolation) as capacity.

These methods mean that published capacity is not the technical maximum, but the business maximum — either in the mind of managers, or based on the interpolated/extrapolated history of business production.

February 7, 2022 at 4:09 pm in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247751We are fond of autonomy and direct democracy — however far-fetched and unattainable it may seem in the capitalized megamachine that rules our world. Some thoughts on the subject:

The CasP Project (particularly the third part): https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/536/

Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

February 6, 2022 at 8:50 pm in reply to: Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources? #247737rk374:

It depends on what we mean by ‘industry’.

1. If we understand industry in the spirit of Veblen — say, as denoting the ‘reasoned application of knowledge, human effort and material resources for the betterment of human and planetary life’ — then industry cannot systematically undermine these goals while retaining a definition that says the very opposite…. In this sense, industry cannot be ‘unbridled’.

2. This claim, though, applies only at a very abstract level. In practice, humans disagree on (1) what constitutes the betterment of human and planetary life, and (2) how the application of knowledge, effort and resources affects human and planetary life. So at this practical level, industry can become ‘unbridled’ to a greater or lesser extent, even in a society committed to these goals.

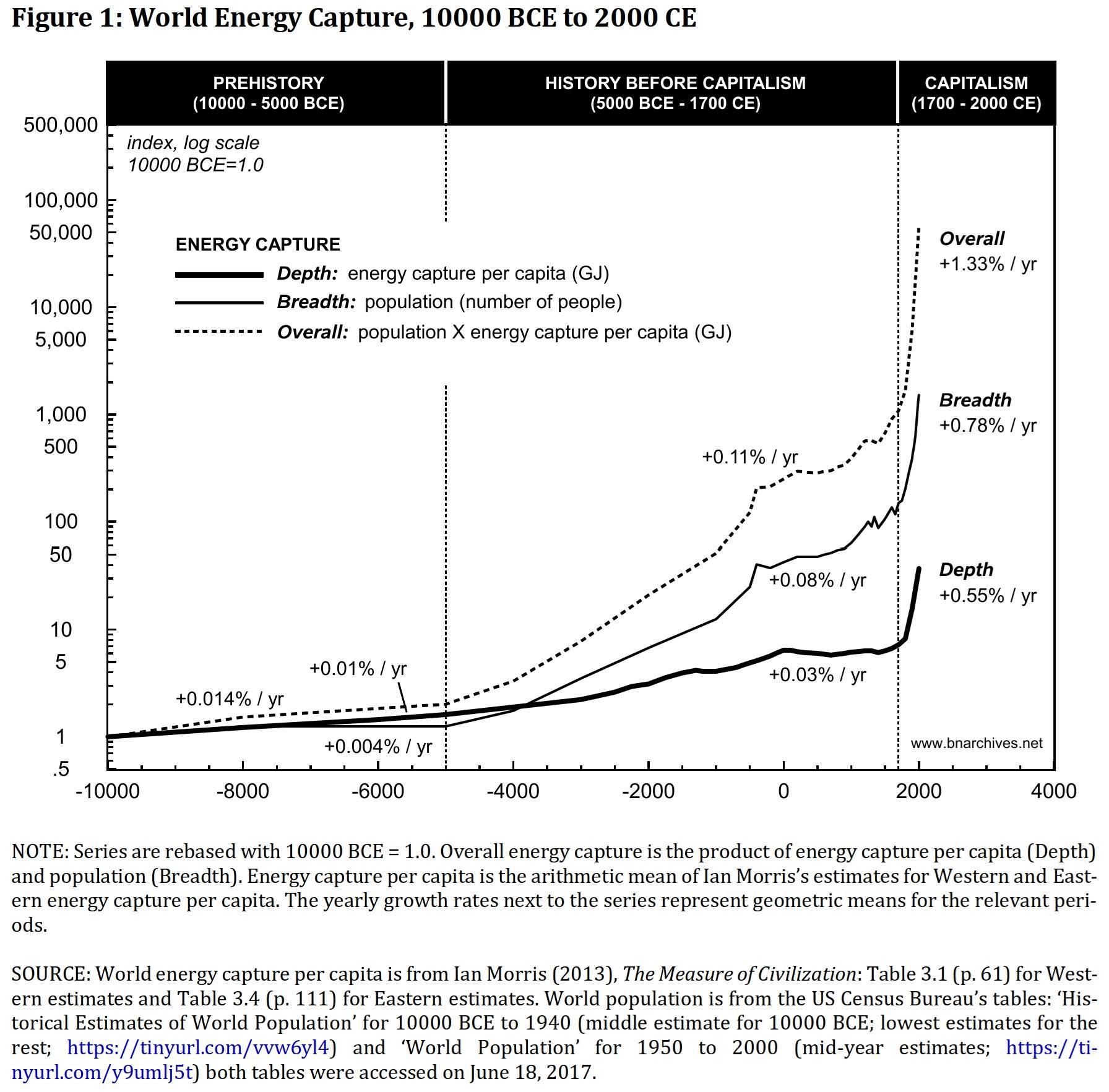

3. But we live in capitalism, and capitalism is driven by business not industry. Following Veblen and Mumford, our CasP theory argues that business undermines industry — i.e., it undermines the ‘reasoned application of knowledge, effort and resources for the betterment of human and planetary life’. But it does not undermine the use of knowledge, effort and resources as such. In fact, as the energy chart below shows, it augments it a great deal. The thing is that, in our view, this augmentation is not directed — at least not in the main — to the betterment of human and planetary life, but to the increase of hierarchical power which sabotages human and planetary life as most people now realize (though often without understanding why).

4. In this context, where a great chunk of our social and physical resources are used and abused for power ends, it follows that their prices don’t represent the ‘right’ or ‘proper’ allocation of resources for the good life of people and the planet (don’t know about ‘utility’, since nobody has ever observed and measured it).

February 1, 2022 at 2:58 pm in reply to: Does CasP Really Have a Theory of Value? Does It Need One? #247697Things became more regularized after 1623 and the rate of useful inventions creating new economic activities accelerated: eyeballing a list in wikipedia and counting what seem to be commercial (as opposed to scientific) inventions I see 1 invention in 16th cent 2nd half 2 inventions in 17th C 1st half 3 inventions in 17th C 2nd half 5 inventions in 18th C 1st half 11 inventions in 18th C 2nd half … and so on. This quickening of invention/entrepreneurship is the beginning of capitalism.

I’m not sure I understand you correctly, but you seem to equate capitalism with a positive rate of growth of invention / enterprise. I wonder how one actually determines such things. For example, should we include language, mathematics, the alphabet, ownership, writing, the wheel, medicine, kingship, marriage, etc. as “inventions” and “enterprise”? If we do include them as such, then we should say that capitalism existed whenever these entities emerged and changed — i.e. from the very beginning of humanity. And if don’t include them, then your definition of capitalism must be made more restrictive.

The ratio exceeds one because many corporations aren’t profitable.

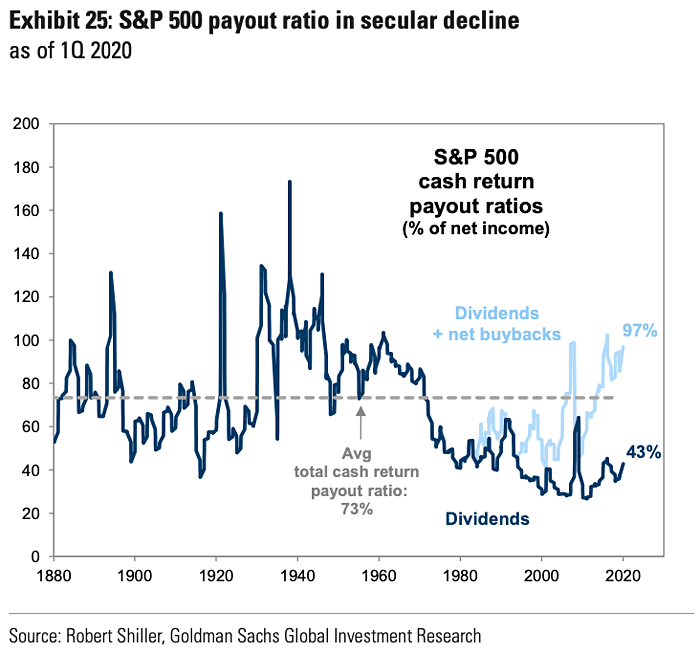

Since the 1980s, the share of net profit in national income has trended upward, and a growing share of these profits has gone to dividends. Currently, dominant capital pays over 40% of its net profit in dividends (and another half in buybacks). It is true that a smaller number of firms pay dividends, but those who do seem to compensate for the shortfall.

But there are plenty of low-grade capitalists (individuals and firms) for whom differential accumulation (as compared to other capitalists) is neither a goal nor a concern, for example.

I’m not sure. I think all capitalists are gripped by benchmarks — the main difference is that most small capitalists are obsessed with meeting the average, whereas larger ones try to and sometimes can beat it.

Is this always the case? One of the reasons I believe Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have such large market caps is because they’ve managed to capitalize the future earnings of those outside of their corporate hierarchies.

The inner hierarchies of the corporations themselves are only one aspect of hierarchical power, and not necessarily the most important one. In Section 3.3 of ‘Growing through Sabotage’ (2020), we classified corporations as micro hierarchies, nested in meso-hierarchies and further in meta-hierarchies. If we consider the full spectrum of social hierarchy, we might find that today’s capitalism is the most hierarchical society ever.

Most companies no longer pay dividends.

The data below are only marginally germane to the broader argument, but they are interesting nonetheless.

This chart is from Blair Fix: https://capitalaspower.com/2015/07/some-important-limitations-of-income-inequality-data/

Here is the U.S. dividend payout ratio. It has risen significantly since the 1980s, and at times it even exceeds 1!

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons.

First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake.

But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.

In the final analysis, capitalism is not governed by individual capitalists, even though it often seems that way. It is not the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Morgans, Soroses, Zuckerbers and Musks of the world that run the show. And it is not even the corporations that they own that stir capitalism. Instead, it is the inner logic of capital that subjugates them all.

So why does CasP put so much emphasis on corporations — particularly the large ones — and on the dominant capitalists and executives that own and manage them?

The answer is that, according to CasP, the inner logic of capitalism is about differential power, and the imperative of differential power drives and creates taller and taller hierarchical structures headed by state-supported large corporations, their top executives and key owners.

By analyzing the various processes of sabotage that leading corporations/government officials/owners/executives engage in and the resistance they face on the one hand, and by contrasting these processes with their differential income, risk and assets on the other, we can draw meanigful conclusions on the changing nature of capital as power.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

1. The series in this figure shows the annual rate of change of the CPI-deflated U.S. stock market index, expressed as a 10-year trailing average. These transformations mean that every annual observation in the series measures the average annual rate of change of the CPI-deflated index over the past 10 years.

2. The chart also marks one and two standard deviations above and below the historical mean of the series.

3. The current level of the series is more than two standard deviations above its historical mean.

4. If I were a betting man, I’d say that the U.S. is about to enter a major capitalist crisis sometime during the next decade.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 11 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 11 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

AuthorReplies