Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

At the very least, though, the concept of a “market” should require the voluntary exchange of commodities, shouldn’t it?

I don’t think so. All monetary exchange involves aspects of power, so in that sense, it is never entirely or even mostly voluntary. But it is never only about power either. In a company town, the power of the company is significant, but not absolute. If it were absolute — like in a slave plantation or a concentration camp — there would be no need for monetary exchange.

The capitalist mode of power is mediated through monetary exchange. And if exchange is a vehicle of power, you cannot assume it away. In this sense, capitalism sans markets is an oxymoron.

But I could be wrong.

Scot,

Your notion of a “market” refers to the neoclassical setting of perfect competition. But this is only one possible setting, even in neoclassical theory. In capitalism, a market is a setting where commodities are exchanged (usually) for money. This is a very general definition that can accommodate any commodity/ies, participants, institutions and patterns of activity.

If you get rid of this concept, how would you describe the reality it refers to?

Thank you Michael Alexander for the interesting note. Three points.

1.

You define:

R = ‘real’ cumulative retained earnings = cumulative (retained earnings / price index).

According to this definition, R is an aggregation of the ratio between two nominal series. I don’t know how this aggregation is a proxy of ‘real’ capital — first, because retained earnings are at best the consequence of ‘real’ capital; and second, because ‘real’ capital, understood as a material/productive entity, is unknowable to anyone and everyone, including economists. Yes, Marxists claim that the ‘capital stock’ is ploughed-back surplus value (incarnated as ‘real’ retained earnings), though you cannot operationalize this claim with historical summation when prices deviate from values (whatever they might be) and when technical change makes existing plant and equipment useless/worthless to an unknowable degree.

2.

You define:

P/R = S&P 500 price index / R = S&P 500 price index / cumulative (retained earnings / price index).

This is a relationship between three nominal indices. It is bounded because the denominator R is a rising series with the same slope as the stock market trend. Take any other rising series with a similar slope — or the stock market trend for that matter — and you get the same result.

3.

I’m not sure I understand your last chart and associated explanation.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Sundry thoughts on the state of capital:

1. What makes the capitalist mode of power unique, is that it offers a universal measure of power relations in the form of differential capitalization (and its underlying elementary particles – differential future earnings, differential hype and differential risk).

2. Differential capitalization is not only universal, but also increasingly encompassing. It penetrates and creorders more and more power relations in society, minute and grand. And this penetration and creordering makes the mode of power – or the state of capital, as we call it – appear in constant flux.

3. This flux is deeply dialectical in that it interrelates the imposition of power and resistance to this imposition in what Ulf Martin (2019) calls an ‘autocatalytic sprawl’: the imposition of so-called rational power elicits ‘irrational’ resistance, which in turn calls for further impositions, further resistance, and so on.

4. In this context, the key question concerns the limits, or asymptotes, of this process. The capitalist incarnation of Lewish Mumford’s megamachine is probably the tallest, strongest and most encompassing the world has ever known. But these superlatives also indicate that it might be pushing against some limits beyond which its autocatalytic sprawl might implode. For more on these limits and their implications, see ‘The Asymptotes of Power’ (2012), ‘A CasP Model of the Stock Market’ (2016), and ‘Growing through Sabotage’ (2020).

5. The conventional conception of the modern state as a distinct entity, related to but conceptually separate from capital, is ill-equipped to deal with these integrated processes. James C. Scott’s notion of ‘legibility’ is theoretically trivial (and ‘not particularly original’, in his own words). Relations of power, by their very nature, creorder the universe on which they are imposed. And the process by which rulers make the terrain legible to them is by no means new. It’s written all over the history of the earliest states (just read Frankfort et al., Kramer and Mumford).

6. What is novel is that the logic of capital creordered a new state of capital out feudalism (see Ch. 13 in Capital as Power) . In this sense, the modern state is a creature of capitalism, just like capitalism is inconceivable without a state. They are two sides of the same thing: the state of capital.

7. Bottom line. Power relations, including those created by states (conventionally understood), can be and often are quantified. But they are quantified in different ways with different principles and distinct units. It is only when these relations are subjected and translated to the universal logic of capital (as power), that they too become universal….

***

Frankfort, Henri, H. A. Groenewegen-Frankfort, John Albert Wilson, Thorkild Jacobsen, and William Andrew Irwin. 1946. The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man. An Essay on Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near East. Chicago: The University of Chicago press.

Kramer, Samuel Noah. 1956. [1981]. History Begins at Sumer. Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History. 3rd rev. ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mumford, Lewis. 1967. The Myth of the Machine. Technics and Human Development. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

Mumford, Lewis. 1970. The Myth of the Machine. The Pentagon of Power. New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

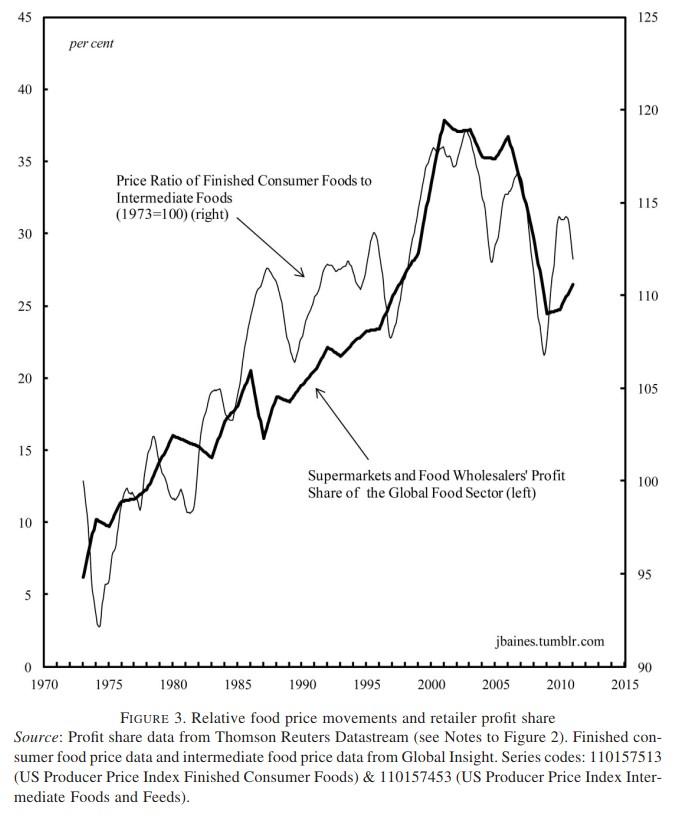

January 6, 2022 at 5:17 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247475Here is Joseph Baines’ 2013 figure updated till 2021, showing how differential inflation continues to redistribute profit well into the present.

Inflation is always and everywhere a process of redistribution.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

January 4, 2022 at 11:34 am in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247474For those interested in reading more on the subject, here is a list of some of our CasP analyses of oil:

- The Political Economy of Armament and Oil – A Series of Four Articles (1989) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/136/

- Bringing Capital Accumulation Back In: The Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition – Military Contractors, Oil Companies and Middle-East “Energy Conflicts” (1995) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/13/

- Putting the State In Its Place: US Foreign Policy and Differential Accumulation in Middle-East “Energy Conflicts” (1996) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/11/

- The Global Political Economy of Israel (2002) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/8/

- It’s All About Oil (2003) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/38/

- Dominant Capital and the New Wars (2004) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/1/

- New Imperialism or New Capitalism? (2006) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/203/

- Still About Oil? (2015) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/432/

- Profit Warning: There Will Be Blood (2017) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/432/

- Still in the Danger Zone (2020) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/634

January 1, 2022 at 7:17 pm in reply to: Costly Efficiencies Working Paper – Critical feedback #247460Hi Chris:

I have a technical point to make.

Your paper looks at the relationship between health expenditures and Covid19 deaths, implying that the former has a varying effect on the latter, depending on the public/private expenditure mix.

Your chars make this implied causality potentially difficult to follow. In the sciences, it is conventional to plot the implied cause on the horizontal axis and the effect on the vertical one. Your figures — such as the one reproduced below — invert this convention. They put the effect on the horizontal axis and the cause on the vertical one. Changing the axes will make your results easier to read.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

December 29, 2021 at 4:34 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247445Relative oil prices and differential oil profits

By Shimshon Bichler & Jonathan Nitzan

***

If you thought that oil profits are about producing oil, think again.

The enclosed chart, updated from our 2015 Real-World Economics Review paper, ‘Still About Oil?’, shows that the main determinant of oil profit — and specifically of differential oil profit — is not output, but prices.

The figure shows the correlation between two series: (1) the differential oil profits of the world’s integrated oil companies, computed as the ratio between their earnings per share and the earnings per share of all listed firms; and (2) the relative price of oil one year earlier, measured by the $ price of crude oil relative to the U.S. consumer price index. (The reason for the annual lag is that ‘current’ profits represent a trailing average of earnings recorded over the past 12 months.)

When we wrote the article in 2015, differential oil profits and the relative price of oil were both at record highs; nowadays, they brush against record lows. And that pattern is to be expected. As the chart shows, the correlation between these two measures remains positive and tight, with a Pearson coefficient of +0.69 for the entire period since Dec 1973, and +0.75 since January 1980.

Inflation is always and everywhere a re-distributional phenomenon.

(And expect differential oil profits to rise next year.)

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

December 27, 2021 at 8:12 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247441This figure is from Joseph Baines’ 2013 New Political Economy paper ‘Food Price Inflation as Redistribution: Towards a New Analysis of Corporate Power in the World Food System’, p. 88.

The chart shows how differential inflation, shown here by changes in the price ratio between finished consumer foods and intermediate goods, altered the profit share of supermarkets and wholesalers in the global food sector.

Inflation redistributes income, practically always, and often systematically.

K/E would give us the price to earnings ratio. I think Blair used the inverse formula: r = E/K Adjusted to include compounded growth: E/K = (r-g)/(1+g) = 0.068 g = 0.04 r = 0.068+1.068g = 0.1107 = 11.07%

Thank you Max. Here is the revised version of the paper, posted as a Working Paper on Capital as Power.

December 16, 2021 at 8:31 pm in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #247384Here is another update in the ‘inflation-is-always-a-redistributional-phenomenon’ series.

The chart below shows two series. The dotted series is the wholesale price inflation. The solid series is the ratio between earnings per share of the S&P500 companies and the average hourly earnings in the U.S. private sector, measured as a % deviation from its past five years (meaning that, if in a particular year the value of this indicator is +40%, it means that the ratio between earnings per share and the wage rate is now 40% higher than its average over the past five years) .

The figure shows that, since the 1950s, inflation redistributed income from workers to capitalists. When inflation increased, capitalists gained relative to workers, and when it decreased, they lost relative to workers.

The chart also indicates that this positive correlation grew stronger in the second half of the period: until 1985, the correlation was +0.35, whereas from 1985 onward, with the exception of the financial crisis years of 2008-9, it almost doubled to +0.64.

Inflation isn’t neutral.

In this model, the higher the (r-g), the greater the ‘capitalist degree of immortality’ for any given number of discounted years.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

K/E would give us the price to earnings ratio. I think Blair used the inverse formula: r = E/K

Thanks for the correction, Max.

Lesson: don’t ignore the seemingly obvious!

Shouldn’t we expect capitalists to already include growing perpetuity of earnings when pricing these kind of assets? If so, Blair’s ‘effective’ discount rate actually corresponds to [r-g]. And if the projected growth rate of earnings is 4%, than the ‘actual’ discount rate [r] is around 12% (instead of 8%). Or am I confusing something?

Good point, Max.

Let’s hope I don’t screw up the algebra:

1. In his paper, Blair used the simple formula r = K / earnings — i.e., without earning growth.

2. Had he used the formula with compounded earning growth, we would have:

K/E = (1+g)/(r-g) = 0.068

Rearranging the equation, we get:

r = (1 + g(1+0.068))/0.068

If g = 0.04, we get r = 0.153, or 15.3%

Are you able to share the underlying data, especially the historical data for r and g (or at least point us to it)?

1. Compounded earnings growth g for the past 150 years is calculated from Robert Shiller’s data.

2. Blair Fix computes the discount rate r for all Compustat firms in the U.S. for 1950-2017, based on the ratio of current profit to current capitalization (i.e. assuming future profits won’t grow), as 6.8%. Since unknown future profits are considered more ‘risky’ than known current profits, we set the discount rate, tentatively, at 8%.

-

AuthorReplies