Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

September 6, 2022 at 11:47 am in reply to: Jujutsu: can we lever the power of capital against itself? #248307

Thank you Pieter for the detailed articulation.

Concepts matter a great deal, particularly when they are key to a whole system of thinking, so it is great to see you engaging with the issue seriously.

Instead of cutting and pasting several pages here, allow me to refer you to our 2020 rejected interview with Revue de la régulation. Question 15 in this interview outlines our notion of power, and Question 16 illustrates how, in our opinion, power is conceived and operationalized in the capitalist mode of power.

As you will see, our view of social power, particularly in capitalism, differs significantly from the received everything-goes plethora of powers ‘over’, ‘to’, ‘with’, etc.

***

Given this discussion, we prefer to think of horizontal, autonomous cooperation not as a different from of power (to, with, etc.), but as the undoing of power. In this sense, to undermine capitalist power is not to convert this power or divert it to other social entities, but to reduce or eliminate it altogether.

This clear distinction saves endless entanglement and never-ending confusion.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Also, what is the difference between “capitalization” as its used here and price/earnings ratios?

These are two distinct, albeit connect concepts.

1) P/E ratio = price per share / profit per share = capitalization / overall profit

In CasP:

2) capitalization = expected future profit / (risk x normal rate of return)

Note that P/E relies on current earnings that are known, whereas capitalization discounts expected future earnings that are unknown.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Note how Blair Fix’s ‘discord index’ shares the same periodicity/trajectories as our own ‘power index’: rising till around 1900, down-trending till the 1980s, and re-surging thereafter (notice, though, that in these charts the discord index is smoothed whereas the power index isn’t).

Blair, perhaps you can create a proper chart of this co-movement.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Path Dependency

Path DependencyThis is Billy Summers’ last job, and, in a sense it is pre-written. It was ‘in the cards’ — or, as a theorist would say, it was ‘path dependent’.

Billy Summers, the protagonist of Stephen King’s 2021 novel, is a gun for hire. And he was bound to be.

As a boy, he shot his abusive stepfather after the man had beaten Billy’s younger sister to death; he spent his youth in a foster home; then, having nothing better to do, he volunteered to the Marine Corps; the Marines sent him to Iraq, where he became a decorated sniper; and upon his return to the U.S, he established himself as a professional assassin. He killed people for a living – but only after ascertaining they were ‘truly’ bad.

His last job – capitalized at two million dollars — is to take down an inmate on the courthouse steps, just as he enters his hearing. The inmate is definitely a bad guy, so Billy’s conscious is clear. But this is a thriller, so things aren’t what they seem to be. Billy senses he himself is next in line, and from there on the plot starts to thicken.

But the plot and its path dependencies are secondary.

Billy Summers is a book you read mostly for King’s gripping storytelling — his portrayal of backwater America, of the gruesome nature of war, of lust – particularly for power and money – and, most importantly, of the frail human psyche.

Highly recommended.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

July 18, 2022 at 5:16 pm in reply to: Comment on “The Aggregate Demand Problem in Capitalism Solved” #248130I’d argue that credit, not wages, is central to all crises.

1. Note that my rough-and-ready description rehashes the convention perspective of economics, not my own view. It is meant to explain why Marxists and post-Keynesian see the general movement of wages as central for aggregate demand, even though it is only a segment of that demand.

2. And yes, credit and capitalization more generally are the key organizing principle of capitalism. But the expansion of credit depends on distributional dynamics. If the wage share trends downward, credit expansion can surely fill the gap — but only to a point. The likelihood of banks lending more and more to increasingly wage-strapped workers and firms with bloated excess capacity is fairly small.

3. The figure below shows U.S. ‘real’ GDP growth along with the overall wage share in gross national income. The chart demonstrates that the wage share rose till the early 1970s and fell thereafter, and that ‘real’ growth followed a similar periodicity. The short-term differences between the series may have been affected by credit, but the long-term trends were not.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 5 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

July 17, 2022 at 1:38 pm in reply to: Comment on “The Aggregate Demand Problem in Capitalism Solved” #248128Why wages are central to economic crises

Crisis is a process of change, which is why economists tend to think of it in terms of growth. When output and employment decelerate, they say we have a recession; when they contract, they call the result a great recession; when they plunge, they speak about depression; and so on. The reason for these oscillations is the subject of ‘crisis theory’.

In line with JB Say’s maxim that supply creates its own demand, most mainstream economists think of crisis as an exogenous, temporary phenomenon. Since every sale is made for the purpose of a purchase, goes the argument, demand is never lacking, and occasional excess or shortage are quickly cleared by flexible, self-equilibrating prices. If the crisis lingers, the reason is always ‘exogenous’: external shock, government intervention, market imperfections – the outside spoiler list is endless.

Keynes critiqued this barter-like conviction. In capitalism, he pointed out, sales and purchases are mediated through money and separated in time, which means that demand can be reduced by saving. And since the incentive to save (withdraw earnings) is often inverse to the urge to invest (inject earnings to create new capacity), lingering recession and depression are possible not only in practice, but in theory too.

Marxists have a developed a full battery of crisis theories, summarized lucidly in Part Three of Sweezy’s 1942 book The Theory of Capitalist Development:

A second generation of crisis theories – post-Keynesian and neo-Marxist – married Keynes’ macroeconomics with Marx’s emphasis on class to examine more closely the impact of income distribution and concentrated market structures (Kalecki, Steindl, Baran & Sweezy, Magdoff, Braverman, Robinson, Kaldor, Eichner, Lee, Lavoie, etc.)

Keynesianism and Marxism, as well as their post- and neo- variants, consider the crisis role of both wage and non-wage income on aggregate demand. But wages are central in the following sense.

Aggregate demand comprises more than the consumption of workers alone. It also includes the consumption of capitalists, their investment in new capacity, the spending of government, and the purchases of foreign buyers.

On the face of it, then, it seems that capitalism can prosper even if labour income falls short of overall income – provided other earners consume, invest and spend enough to compensate for the shortfall.

But the analytical possibility of non-labour demand growing to compensate for the falling consumption of workers, argue Marxists and post-Keynesians, is tenuous in practice. Capitalist consumption is limited by the capitalist need to invest. Rising governments spending is restricted by the overriding logic of free enterprise. And most importantly, current investment is determined by the expectation of future demand, and since this demand depends mostly on workers’ consumption, investment is highly sensitive to the prospect of reduced wages (export demand is subject to all these limitations).

So, in the final analysis, wages, although making only part of aggregate demand, are central to all crises.

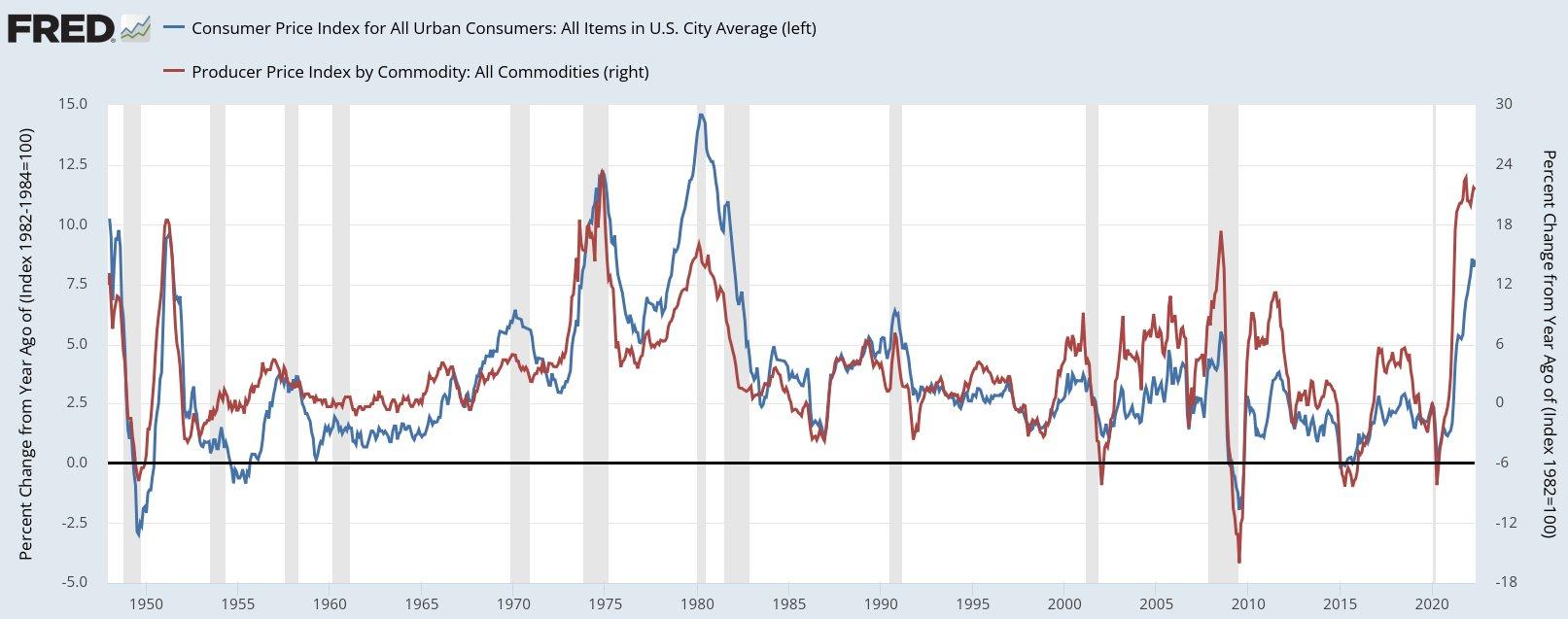

June 25, 2022 at 7:34 am in reply to: Inflation is always and everywhere a redistributional phenomenon #248114The May 2022 data for the United States, shown in the figure below, suggest that the current bout of inflation may be peaking. The chart contrasts the annual rate of change for consumer prices (left) with that of producer prices (right), and both series indicate that the process may be approaching its upper limits.

The reason for these limits has to do with the re-distributional essence of inflation.

Inflation is an average of individual price changes, and this average hides the most important driver of inflation: the fact that individual prices change and different rates, and that these differences redistribute income and assets.

The next chart contrasts the annual CPI inflation in the United States (red) with the annual rate of change of the purchasing power of wages (blue) — or what economists call the “real wage.” Note how the two series are inversely correlated: when CPI inflation accelerates, the rate of change of “real wages” decelerates, and vice versa.

This negative correlation suggests three things.

1. U.S. wage earners tend to lose from inflation — when inflation rises, U.S. wage increases tend to lag (and, inversely, rise faster when inflation slows). And since, on the upswing, wages rise more slowly than prices, the purchasing power of wage earners suffers.

2. Wage increases do not cause inflation — unless you insist on blaming workers for using wage increases to give capitalists the excuse to raise prices even faster.

3. Redistribution tends to limit the inflationary process — as inflation redistributes income from workers to capitalists, it undermines workers’ income-read-consumption, causing the the profitability of price-setters to gradually wane. Eventually, capitalists lose their price-hike resolve, their tacit coordination fractures, and inflation decelerates.

Is anyone aware of work done to “map” the financial system? […] I think an institution-driven mapping of financial networks would be more informative for understanding the state of capital.

Agreed. Such institutional mapping — particularly when quantified — would be highly useful. Creating it, though, would require expert familiarity with the financial process.

Thank you for posting DenimGod’s response.

In terms of what concrete strategy I am advocating for, my interpretation of CasP is it implies organizing an alternative reciprocating economic machine outside of capitalism to provide for peoples’ needs without using currency, which will reduce the expected future revenues and capitalizations of corporations.”

There are endless ways of ‘contesting’ capitalism through alternative forms of autonomous cooperation. The trouble with these forms of cooperation is that they do little or nothing to undermine capitalism and therefore end up being defeated or swallowed by it.

In our ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory‘, we suggested a cooperative alternative, that, if successful, could undermine capitalism by starving the financial market. In principle, this end can be achieved by democratically managed housing and pensions, creating the beginning of autonomous society while siphoning liquidity away from the stock and bond markets. The challenge is to make this thing happen on a large enough scale.

Consider this figure, taken from our 2021 post ‘Dominant Capital and the Government’. The chart shows that the power of U.S.-based dominant capital, measured by the differential EBIT of the top 200 firms, has been stagnant — albeit at record highs — for over a generation.

If asset management is a way of boosting this power hierarchy, it hasn’t succeeded. And if it is a means of creating a new hierarchy of power, what is this new hierarchy?

Asset management firms themselves are large, but judged by their earnings and capitalization they aren’t very significant compared to dominant capital as a whole (say the top 500) — though I may be wrong on that.

May be of interest:

Rosenthal, Caitlin. 2016. Slavery’s Scientific Management. Masters and Managers. In Slavery’s Capitalism. A New History of American Economic Development, edited by S. Beckert and S. Rockman. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 62-86.

Rosenthal, Caitlin. 2018. Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Income received in recompense for human effort.

In my view, shifting from ‘productive contribution’ to mere ‘effort’ still leaves us with no solid basis to justify/critique income.

1. Pure (absentee) owners may argue that, while they exert no current effort here and now, their income compensates for past effort — theirs or their predecessors’.

2. For those who do exert effort, we don’t know whether their effort affects production positively or negatively, and by how much.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Yes, ownership per se does not affect production — a statement we both seem to accept — but it also means that provision of inputs as such cannot be a yardstick for earned income.

So we are left with earned income = income of those who participate directly in production.

But what does it mean to ‘participate directly in production’? If Bezos goes to work one day a month, should we count him as participating and his income as earned? If I’m digging holes and filling them up, do I participate in production? If someone manages a chemical weapon company, sells advertisement, produces cigarettes, or runs a bank, is their participation productive?

It seems to me that production is an incoherent basis for classifying income in capitalism. It is also too narrow a focus for organizing a democratic alternative.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

Many thanks Steve for the interesting posts, though I must say they leave me puzzled.

You write:

Earned income is received by households, people, in compensation or reward for doing things: providing inputs to production. The remainder, all other tallied household income, is unearned.

.

What do you mean by ‘doing things’ and ‘providing inputs to production’? For example, don’t owners of land — the most notorious ‘rentiers’ — provide inputs to production, as do owners of ‘capital goods’? According to your definition, their incomes are as ‘earned’ as those of workers.

In our work, we argued that the problem with the ‘earned/unearned’ distinction hasn’t changed since the physiocrats. Despite endless claims to the contrary, nobody knows the ‘true production function’ because no such function exists. Production is a hologramic societal process. Its ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ cannot be objectively identified, they have no universal units, and their complex cross-section and temporal intricacies cannot be disentangled.

Unless we decipher ‘who’ produces and ‘what’ they produce, how are we to conclude who earns and who doesn’t?

- This reply was modified 3 years, 7 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

4) Hence one of the problems I would like to tackle: the relation between point ‘1’ (neuropsychoanalysis) and point ‘2’ and ‘3’. Being ‘happy’ or ‘mentally healthy’ is a thing, being happy or mentally healthy because big corporations know that “happy” employees are more productive (or less prone to question authority) in the workplace is completely another thing. Moreover, all this raises questions that remind me of the famous paper by Marglin ‘What do bosses do?’ in which he demonstrates how technological developments (machines) in the early stages of capitalism were a means to better control people, and not to raise productivity. Maybe we could make a similar case for big corporations’ will to harness our ‘SEEKING’ systems?

CasP research typically comprises two steps: (1) a qualitative hypothesis that identifies a specific power process, examines its evolution and reasons its underpinnings; and (2) a quantitative analysis that demonstrates how this power process appears as systematic differential accumulation.

The second step is as important as the first and tends to be much harder.

-

AuthorReplies